Chris Dillow's Blog, page 97

July 23, 2015

Corbyn's success, Labour's shame

When Graham Dilley went out to bat in the famous 1981 Headingley test match, Ian Botham told him that "we wouldn't survive long just blocking, so we might as well have a swing." This same reasoning, I suspect, explains Labour members support for Jeremy Corbyn.

If the choice were between an election victory under, say, Andy Burnham or a defeat under Corbyn, most Labour members - though perhaps not all - would support Burnham. But that's not necessarily the choice. Maybe Labour will lose under any leader. If so, they might as well follow the Botham principle and have a swing. As Paul Bernal says. "If the Labour world is going to end, let it end with a bang, not a whimper."

And Corbyn is the only candidate offering a bang. Neil Schofield, James Bloodworth and Richard Murphy all agree that his popularity reflects a disaffection with the "mainstream" candidates who prefer to collaborate with the Bubble than talk about principles.

What's more, there is a chance - not high, but maybe better than 500-1 - that Labour could win under Corbyn. Voters agree with some of his positions, for example on higher top taxes and renationalizing the railways. His unpoliticiany ways could appeal to those many voters who are antipathetic to Westminster and appreciate people who talk their minds. And remember the old adage: oppositions don't win elections; governments lose them. Maybe dissatisfaction with austerity, Tory splits over Europe or an economic downturn would hand Labour victory under anyone.

In this context, I'm not sure Sunny is right to say that Corbyn would repel Ukip voters. Ukippers have quite "leftist" attitudes in some ways. As Matthew Goodwin points out, most of them agree that there's one law for the rich and one for the poor, and most support (pdf) nationalization and price controls; they want control of immigration because they want control of much of the economy. There's potential support there for Corbyn.

Which brings me to my problem. What strikes me about Corbyn is just how uninspiring his economic programme is. I fear his proposed austerity for the rich and for companies will prove as macroeconomically self-defeating as the Tories version of austerity has been*. And there's disappointingly little about worker ownership or what to do about stagnant productivity, job polarization, the threat of robotization (pdf) or the possible transition to post-capitalism.

If this is the best Labour can do, then the party really has run out of intellectual resources.

* That said, there might well be a case for abolishing corporate tax relief for debt (pdf) interest payments - one of the tax reliefs of which Corbyn complains.

July 21, 2015

Reality vs the Bubble

Last night's vote on the Welfare Bill shows that Labour is divided. The division though, isn't so much between left and right as between reality and the Bubble.

The Bill will cost the poorest (pdf) families hundreds of pounds per year, increase homelessness and child poverty (pdf) and create insecurity for many low-paid workers who are at high risk of losing their jobs*. And its motives are based in large part upon myths - that welfare spending is a burden, that there's a pressing need to cut the deficit, and that there are distinct groups of workers and claimants rather than constant movement between them.

What we have, then, is a divide. On the one hand, there is the reality of increased misery for hundreds of thousands. On the other, there is the Bubble of Westminster politics which has created economic lies and which regards cuts to welfare merely as a political game between Osborne and Labour. The poor have no place in this Bubble and thus no voice**.

No Labour MP, who has the foggiest idea of what the party is for, could in good conscience, possibly do anything other than oppose the Bill.

But there's the rub: "good conscience". The case for abstaining is that sometimes bad conscience is necessary. Labour, it's said, must obey the rules of the Bubble by appearing "moderate" and not the party of welfare.

I happen to agree with Simon that this is bad strategy. If the debate is framed in Bubble terms in which welfare is a burden rather than insurance, Labour will always appear "weaker" than the Tories. And there is a big danger that Labour will actually come to believe its own lies and so lose any vestigial reality-based principles.

This, though, is the issue. There can be no question that from any left-of-centre view, the Welfare Bill is terrible - and its ally, cuts in tax credits, even more so. The reality is clear. What's not so clear is whether reality matters any more.

* The big cuts in workers' incomes because of Osborne's cuts to tax credits are not part of the Bill.

** Compare the debate about welfare cuts to the Labour's proposed mansion tax. Whereas the potential losers from the latter were high-profile, the losers from the former are largely nameless. This matters, because the mere act of communication increases sympathy.

July 19, 2015

Labour's economic narrative

I like Paul Bernal's description of Blairites as like Elvis impersonators who only impersonate the old, fat conservative rather than the younger radical man.

I'd add that one way in which this is true is that the young Blair had a distinctive economic narrative. Globalization and technical change, he said, were transforming the economy and required new policies - such as more education because low-skilled jobs were disappearing overseas, and macroeconomic stability to attract and retain investment.

This narrative had its faults. But it was an act of genius compared to the fiction that dominate politics now - the pretence that all was well with the economy until Labour "over-spent."

What Labour needs is a new economic narrative. It should consist of a diagnosis and solution to five problems:

1. Secular stagnation. The refers to the combination of slower innovation, low investment and weak productivity growth that have given us slower growth in real incomes: the IFS says median real incomes have risen only 0.4% per year in the last 10 years compared to 2.2% per year in the previous 40. Any serious economic policy would have ideas about what to do about this - be it more state intervention to encourage investment, or serious policies to raise productivity.

2. Job polarization. Middling-income jobs are in decline - and might continue to be as robots replace (pdf) people. This makes social mobility even harder - because some rungs of the ladder are missing - and means that better jobs might not be a way out of in-work poverty.

3. The rise in the share of incomes going to the top 1%. Is this a problem? If so, what to do about it?

4. Limits of managerialism. Between 1997 and 2010 public sector productivity stagnated. This suggests that top-down management and targets might not be sufficient to raise efficiency. Which poses the question: what are the alternatives? Given that there are already signs that austerity has gravely deteriorated some public services, this question might become increasingly important.

5. Decorporatization. The numbers of self-employed have risen sharply in recent years. Is this a sign of the failure of mainstream employers to offer satisfying work? If so, is this temporary or long-lasting? Or is it the start of an "interstitial (pdf) transformation" towards post-capitalism? Given that this process threatens to squeeze profits and hence capitalist investment - as spending shifts to the non-corporate sector - should it be encouraged or not?

FWIW, my answers to these questions comprise supply-side socialism - such as a citizens income and worker-ownership and Brailsfordism. But that's not my point. My point is that an intelligent Labour party would need to tackle these issues. The right of the party needs some kind of narrative to resist the rise of Jeremy Corbyn. And the left needs to see that an economic policy must do more than merely oppose austerity.

July 16, 2015

The Cushnie principle

There is, understandably, a backlash against the government's proposal that women who want to claim tax credits for a third child must prove they have been raped. For me, this highlights the importance of the John Cushnie principle.

Mr Cushnie was a star of Gardeners' Question Time whose reply to many questions was: "it's not worth the bother."

This answer applies to a lot of the welfare state. Maybe it is a good idea to limit tax credits to two children. But is it worth the bother, in terms of bureaucracy and intrusion and bad PR? Maybe you think claimants should prove they are seeking work. But is it worth the huge cost of finding out? Maybe benefits should be sensitive to variations in need? But again, is it worth the administrative cost?

Perhaps your ideal welfare state would entail many complicated gradations of need and desert. But these run against the Cushnie priniciple: it's not worth the bother. For me, one virtue of a citizens' income is that it avoids the deadweight cost of administering so many fine distinctions.

Of course, the Cushnie principle broadens. It's one reason why I advise my readers to hold tracker funds. Granted, it's possible that momentum, value, defensive and quality stocks would, over time, out-perform. But it might not be worth the bother of complicating one's investments so much.

Readers will recognise the Cushnie principle. It's an expression of Herbert Simon's theory of satisficing. We often lack the knowledge and rationality to maximize, he said, so why not make do with reasonable simple rules? But the Cushnie principle goes a little further, by seeing that an attempt at maximization might not just be impossible, but counter-productive. For example:

- There's the unnecessary labour in gardening or investing, policy-makers equivalent of which is the cost of bureaucracy. Of course, true maximization would take account of these costs. But it's easy to under-estimate them - thanks to the planning fallacy - as Iain Duncan Smith discovered with universal credit. How often do politicians say: "the cost of this scheme has come in way under budget"?

- In politics, the pursuit of the best policy might lose one political capital, which would be better expended upon higher priorities.

- Trying to maximize can make us vulnerable to cognitive errors. One virtue of tracker funds is that they protect us from the countless biases that worsen investment performance.

- The best can be the enemy of the good. In that wonderful film Whiplash Terence Fletcher's pursuit of genius destroys the lives of musicians who would have had perfectly decent careers. Similarly, investors who chase high returns end up over-paying for poor performing lottery-type stocks. And as John Kay has shown, attempts to maximize shareholder value can lead to corporate failure, for example by demotivating employees and encouraging corruption.

In these ways, the Cushnie principle has many applications. There's more wisdom in gardening than in politics.

July 15, 2015

Three paradigms of maximization

Danny Finkelstein in the Times says game theory is often too complicated to solve real world problems. He's right, if you try to use it to get precise solutions. But it has another use. It reminds us that there are (at least) three paradigms in economics and it matters enormously that we know which paradigm is relevant for which problem*.

One paradigm is parametric maximization: we maximize expected utility subject to given parameters.

This, though, isn't universally applicable, as the two envelopes problem teaches us.

Imagine I give you and a colleague an envelope each. I tell both of you that one envelope contains twice as much money as the other. I then ask you if you want to swap, paying me a small sum if you do.

Conventional maximization suggests you should swap. You figure: "I have a 50% chance of a 100% return and a 50% chance of a 50% loss. That's an expected value of plus 25%."

If both of you think like this, you'll both pay me to swap. But having swapped, the same reasoning applies again. So you'll both swap again. Each time, I get richer and you two get poorer.

The error you're making here is that parametric maximization doesn't apply. Your colleague is not a given parameter but a strategic thinker just like you. Once you see this you see that the game theory paradigm applies and so cease to be an egocentric framer. You figure "if he wants to swap envelopes, why should I do so?" You thus reject the trade and the logic that impoverishes you.

This is no mere thought experiment. One of the best-attested anomalies in finance is IPO under-performance; newly-floated stocks tend to do badly (pdf) in subsequent months. I suspect that one reason investors fall into this trap is that they apply the wrong paradigm. They think they are in the domain of parametric maximization and try to maximize expected returns for given prices but in fact they should apply the game-theory paradigm, and ask: if well-informed owners of the firm want to sell, why should I buy?

This isn't the only way in which getting the paradigm wrong can be costly. Governments or managers who set targets which are subsequently gamed make the same error. They think they are in the domain of parametric maximization when in fact they are in the game-theory domain: they forget that subordinates are not mere pawns to be moved, but strategic agents. (The Lucas critique makes a similar point about macroeconomic policy.)

However, there's a third paradigm - entrepreneurship. Introductory textbooks tell us that bosses try to maximize profits subject to given costs and technology. The entrepreneur, however, doesn't take these as given but rather tries to discover new technologies or newer cheaper suppliers. As Schumpeter said, he does things that "lie outside of the routine tasks which everybody understands." There's a thin line between the entrepreneur and the criminal because both try to break established rules.

Again, the failure to see which paradigm applies can be expensive. And not just in business but in politics too. The 1929-31 collapsed because it tried to impose austerity to keep the UK on the Gold Standard. When the subsequent coalition government took us off that standard, Sidney Webb, a Cabinet minister in the Labour government said: "nobody told us we could do that." This suggests the Labour government had been stuck in the parametric paradigm, when it should have applied the entrepreneurial one. Sometimes, constraints are only illusory.

Some of you might think the Labour party now is making the same error - of regarding public opinion and mediamacro as given parameters rather than trying to change them.

Maybe. But in business and in politics, entrepreneurship often fails. The parametric paradigm is often the right one. And sometimes - often - we just can't know whether it is or not.

* I'm talking here about fully rational maximisation: let's leave behavioural economics aside for now.

July 14, 2015

In defence of welfare

The Guardian says Harriet Harman is worried that Labour "will be viewed as the party of welfare, not work". This is unfortunate, because someone must stand up for welfare.

First, let's remember that working-age welfare recipients are, to some extent, not a fixed group so much as people who are temporarily out-of-work through illness or unemployment. ONS statistics show that in Q1, 886,000 people of working age moved out employment into either unemployment or inactivity whilst 509,000 moved from unemployment into work (27% of all unemployed) and 573,000 moved from inactivity to employment. For these reasons, only 326,000 of the 1.8 million people out of work have been unemployed for more than two years.

Except for the ill and disabled, there is not so much a bunch of claimants and bunch of workers, but rather people who shift from one category to another.

Welfare is, therefore, a form of insurance; we pay in in good times and get a payout in bad.

In fact, this is true in two other senses.

For one thing, welfare acts as a form of automatic stabilizer; higher welfare spending in bad times helps to support aggregate demand and so moderates recessions.

This matters. Recessions are unpredictable. Neither monetary nor fiscal policy can prevent them, therefore, simply because they cannot be loosened sufficiently before the recession becomes obvious. We need, therefore, a timelier and more automatic protection against downturns. Welfare spending is that protection.

And it protects us all. Benefits aren't so much a payment to claimants as a payment through claimants. They are spent at Primark and Lidl, and so support employment there. The distinction between welfare and work is therefore a false one; welfare helps to create jobs.

There is, though, a third way in which welfare is a form of insurance.

Imagine we were behind a Rawlsian-type veil of ignorance in which we did not know what type of employability we would be born into. Reasonably risk-averse types would, surely, agree upon some type of insurance whereby less employable types would get an income, paid for by the more employable. We can think of the tax and benefit system as replicating the sort of transfers that we would freely agree to behind the veil of ignorance. In this way, the benefit system corrects a market failure - our inability to buy insurance before we are born.

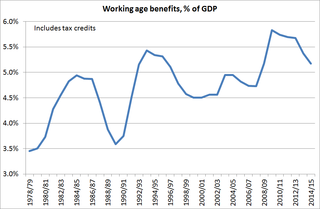

Given all this, what's remarkable is how small is the welfare state. Spending on benefits for children and working people, even including tax credits, amounts to just over five per cent of GDP.

Herein lies a paradox. Developments since the 1970s have actually strengthened these arguments for a strong welfare state. The collapse of demand for unskilled workers has increased the case for transfers to the less employable, because these have suffered the bad luck of being alive at a time when being unskilled carries a greater penalty relative to being more employable. And one reasonable inference from the Great Recession is that we need a bigger welfare state precisely because - given the failure of timely monetary and fiscal policy - we need more automatic stabilizers. And yet politicians seem to have drawn the opposite inference.

Of course, there is much wrong with the welfare system - I'd prefer a citizens basic income - but let's remember that there is a strong case for welfare. If or when the Labour party finds either a brain or a backbone, it might make this case.

July 12, 2015

Labour's failure

There's agreement across the political spectrum that Osborne's Budget was good politics but bad economics. This poses the question: how can a Budget which deprives millions of the worst off of hundreds of pounds a year possibly be "good politics."

Part of the answer, of course, is that the judge of what counts as "good politics" is the Westminster bubble. This bubble is isolated from economic truth - it has convinced itself that austerity is good economics - and has also succeed in marginalizing the low-paid, by pretending that "middle England" comprises people on handsome incomes.

In this sense, the media conforms to Adam Smith's claim, that we have a "disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition" (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.28).

Given this deference and distorted reality, it is no wonder that Osborne should get so many plaudits*.

There is, though, another reason why the Budget is "good politics." It's because the Labour party ceased to be the party of workers and become a party for workers. Rather than be a vehicle whereby workers can advance their own interests**, Labour became a managerialist party, offering workers just so many crumbs from the table as capitalists could spare. This has allowed Osborne to pretend to steal Labour clothes by proposing a high minimum wage.

However, the managerialist takeover of Labour wasn't just bad politics in the sense of allowing the Tories to pose as the party for working people by lifting its policies. It's lousy economics too, in two senses.

One is that the best way to raise wages is to raise productivity.And a good way of doing this is to have greater worker control of firms and less top-down management: it was - remember - the latter that contributed to the collapse of banks.

The other is that policies that increase workers' bargaining power - such as fuller employment, stronger trades unions, a citizens' income that allows workers to reject bad jobs - are surely better ways of raising wages than a mandatory "living wage."

Now, I'll concede that my scepticism about the impact of minimum wages on employment might be excessive: we just don't know. What we do know, though, is that stronger bargaining power is surely a better way of raising pay without jeopardising jobs than an NMW. The former permits wages to rise where they are due to monopsony, but tolerates them where they are due to genuinely low marginal products. A legal NMW doesn't make this distinction and so is, as Martin Wolf says, a crude "leaden-footed regulatory intervention."

Sadly, because Labour has ceased to be a party of workers, and become just another Westminster-managerialist faction, it cannot make these points and cannot distinguish itself from the Tories.

The optimist in me can see glimpses of Labour grasping this fact - for example in Liz Kendall's call for worker representation on boards. Of course, that doesn't go far enough. But it is the direction Labour must move in.

* The BBC is complicit in this. If Osborne were to say the world if flat, Robert Peston would report that there's a debate about the shape of the world. I fear the fault here is less a personal one than an organizational one: the BBC's "due impartiality" requires it to be impartial between truth and falsehood.

** Labour has, of course, always been split along these lines, being a coalition of middle-class do-gooders and trades unionists. It is only recently, though, that the former became so dominant.

July 10, 2015

Minimum wages & jobs

I woke up this morning with a slight headache, so I took a paracetamol and now feel fine. But if one paracetamol makes me feel OK then surely a hundred will make me feel fantastic.

You might spot an error in this thinking. It is, though, the same mistake that some critics of me (and Tim Harford and Martin Wolf and Ryan Bourne) are making when they question our hostility towards the proposed rise in the minimum wage.

I'll grant that most studies (pdf) of the impact of the UK minimum wage have found no significant impact upon employment - although (pdf) there () are exceptions to this (pdf). But there's a reason for this; the NMW has been set at a low level. The Low Pay Commission has helped ensure that the NMW has been administered in a safeish dose. But it does not follow that a higher NMW would be safe. Just as paracetamol is safe in a low dose but dangerous at a high one, so too are minimum wages. The fact that most - not all but most - international studies show that minimum wages do reduce demand for labour shows us that, where they are set carelessly, they can do harm.

Let's consider three possible ways in which this view might be wrong.

First, employers might simply accept a squeeze on profits. However, which this might be tolerable for small wage increases, it'll not be possible for bigger rises which might make the difference between profit and loss. Firms which struggled by on a modest NMW might shut if there's a higher one.

Secondly, firms might respond to higher wages by increasing efficiency; there's some evidence that this has happened, and it is possible because there is a long tail (pdf) of badly managed firms where efficiency gains might be made. Three things, though, make me question how far this is possible:

- Whilst it might be possible for firms to raise productivity by one or two per cent, the big gains necessary to offset a 13% rise in the NMW (on the OBR's estimate) might be harder to find.

- Efficiency in this context often means work intensification: chambermaids cleaning more hotel rooms, care workers seeing more clients, and so on. This means workers might pay for higher wages with more stress.

- If productivity is to rise without job cuts, then output must increase: this follows from the definition of productivity. But how will this extra output be sold? One possibility is that aggregate demand rises. But, in tightening fiscal policy, Mr Osborne has done nothing to permit this. The other possibility is that firms will cut prices. But the OBR expects the opposite to happen.

Another way in which a higher minimum wage might be consistent with rising employment is if there is monopsony - if workers are paid less than their marginal product.

Again, I'll concede that this might be true (pdf) in some cases. However, a much better way to tackle the problem of monopsony is to increase workers' bargaining power - through stronger trades unions, out-of-work benefits which are high enough to allow people to reject rip-off job offers or through a full employment policy. These allow wages to rise where workers are under-paid without forcing wages above marginal product, which would destroy jobs. However, Mr Osborne has rejected these alternatives in favour of the blunt instrument of a law which bears equally upon monopsony and upon competitive labour markets. This is surely sub-optimal.

My point here is a simple one. The economy doesn't operate exactly as the textbooks say. Wages aren't exactly equal to marginal product and firms don't operate at maximal efficiency. Instead, as Adam Smith said, there is a great deal of ruin in a nation. This ruin provides room for minimum wages to rise a little without hurting jobs. But is it really plausible that there is so much ruin as to permit a big rise without adverse effects?

Mr Osborne has given us no reason to think this. The kindest thing one can say about his plan is that it is a bold experiment. There are less kind things.

July 9, 2015

The worst of left & right

David Cameron once described himself as the "heir to Blair." However, whereas Blair tried to combine the best features of left and right, yesterday's Budget combined the worst.

We saw the worst form of right-wingery in the attack upon low-paid workers. Let's be clear here. The proposed rise in the living wage - from ��6.50 an hour now to ��9.35 by 2020 does NOT offset the reduction in tax credits. The OBR estimates that the higher living wage will add ��4bn to total annual wages by 2020, assuming no change in hours or employment (I'll come to this). But the cuts in tax credits are worth ��5.8bn (measures 39-43 of table 2.1). ��5.8bn is more than ��4bn.

Those working part-time will suffer some massive losses even if they benefit fully from the proposed living wage. Monique Ebell at the NIESR estimates that a family with one child where one adult works 30 hours a week at the current NMW will lose ��492 per year by 2020. The Resolution Foundation estimates that a single parent working 20 hours per week on the NMW will lose ��1000 a year. The SMF agrees.

��10-20 per week might not seem much to those of us who are well-off - but it's a massive amount for those struggling to make ends meet.

Mr Osborne has contrived to combine this impoverishment of the worst off with one of the worst vices of the left - an under-appreciation of the role of incentives.

One way in which this is the case is that he has worsened incentives for the low-paid to work more or get better jobs. Ms Ebell points out that the increased taper rate for tax credits now means that a family earning more than ��11000 per year but getting tax credits faces an effective marginal tax rate of 79%.

There is, though, another way in which Mr Osborne has paid insufficient heed to incentives: he is under-rating the fact that if you raise the price of something, you give people an incentive to buy less of it. It's for this reason that most advocates of a living wage saw it as an aspiration rather than something that could be enacted by law.

Raising the effective minimum wage by 44% over the next five years will encourage firms to reduce employment and hours. By how much?

The OBR (pdf) estimates that the living wage will cut 60,000 jobs.

This, though, is only half the damage. It estimates that the other half of the adjustment will come from cuts in hours.

And even this might be an under-estimate. It is based on the assumption of a price-elasticity of demand for labour of minus 0.4 - one based upon this paper (pdf).

However, it's likely that the elasticity of demand for sub-groups of workers is higher than that for the workforce as a whole, simply because employers can substitute between one group of workers and other groups more than between workers and capital alone. The NIESR's Rebecca Riley has estimated (pdf) that, for unskilled workers, the price elasticity of demand is 0.9 for over-30s and 1.6 for 15-29 year-olds. Applying the former elasticity more than doubles the cost of the living wage relative to the OBR's estimate. That implies a cut in labour demand equivalent to over 250,000 jobs.

Note here that the living wage will not apply to under-25s. It's possible therefore that employers will substiute away from workers in their late 20s to those in their early 20s. Whilst this might reduce youth unemployment, it could hit hard people with young families.

Some of the more honest right-wingers see this for what it is. The IEA's Mark Littlewood calls it "intellectually bankrupt."

I agree. We cannot give ourselves pay rises merely by legislative fiat. Instead, we need a more skilled workforce and companies who want to use those skills. Achieving this requires much more than despatch box rhetoric.

July 7, 2015

Welfare state trade-offs

You wouldn't guess it from some of the more simple-minded calls for cuts in welfare benefits, but changes to welfare spending involve some tricky choices. Here are a few of the trade-offs involved:

1. A big welfare state vs cyclical risk. The fact is that recessions (pdf) are unpredictable. This means that monetary and fiscal policy cannot prevent recessions because policy-makers cannot see them coming. In this context, a big welfare state acts as an automatic stabilizer, ensuring that people don't suffer big falls in income if they suffer job loss or cuts in their hours.

UK history is consistent with this. Between 1831 and 1914, when we had little welfare, the standard deviation of annual GDP growth was 2.5 percentage points. Since 1946 we've had a bigger welfare state and less volatile growth - 2.1 percentage points.

You might object that, because a big welfare state implies higher taxes and lower work incentives, this implies a trade-off between the stability and rate of growth. The evidence is ambiguous. If we look at 33 main OECD economies since 2000, there is indeed a negative correlation (of -0.24) between cash benefits as a share of GDP in 2000 and subsequent growth in GDP per head. However, this is driven by some poorer countries (such as Korea) having low benefits in 2000 but enjoying GDP convergence. If we control for the level of GDP in 2000, the correlation between benefit spending and subsequent growth is statistically insignificant.

2. Risk vs incentives. Low unemployment benefits might incentivize people to find work, but they also increase the risk of job loss. This might be inefficient. If low unemployment benefits cause people to take the first job they can get, there'll be inefficient matches between workers and vacancies. Or the fear of joblessness might encourage workers to invest more in general skills and less in job-specific ones, which could also reduce productivity.

3. Incentives to work vs incentives to work more. Tax credits which top up wages increase the incentive to move into work. For this reason, the CPAG has warned that cuts to tax credits might reduce the incentive for single parents to work. However, high withdrawal rates might of tax credits dampen incentives to move to a better job.

Where you stand on this trade-off should depend upon your view of the labour market. I suspect that if we are in an era of job (pdf) polarization, there's little point incentivizing the low-paid to get better jobs because such jobs won't be readily available.

4. High marginal withdrawal rates vs targeting. Given the existence of tax credits, we have a choice. We could target them at the low-paid, but this would mean withdrawing them rapidly as people's incomes rise. Or we could withdraw them more gently, but this would mean paying credits to people on relatively high incomes.

Reasonable people will differ on these trade-offs. And our choices will depend upon our view of the economy: how volatile is output? Are labour markets supply- or demand-constrained? How is socio-technical change affecting the availability of different types of job? And so on.

What our choices should not depend upon, however, is some arbitrary decision to cut spending based upon deficit fetishism. To do this is to place more importance upon meaningless statistics than real human lives - and this is not conservatism, but Stalinism.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers