Chris Dillow's Blog, page 100

May 15, 2015

Hating libertarians

Tim Worstall, Bryan Caplan and Tyler Cowen have been wondering why people hate libertarians.

I'm not sure many do: if you want to see hate, just look at the abuse dished out to even the most innocuous feminists. But let's grant the supposition. I'd add four reasons to those offered by Tyler, Bryan and Tim.

The first lies in what Bryan called the libertarian penumbra. Some libertarians associate themselves with people who have very rum views: IQ-obsessives, climate change deniers and borderline racists. Libertarianism thus gets discredited by association. As a Marxist, I know this feeling.

Secondly, some libertarians look like shills for the rich. They don't try hard enough to point out that many inequalities actually emerge from state intervention.

Thirdly, some self-described libertarians are simple hypocrites. The most egregious examples of this are Ukippers who are hostile to the nanny-state and yet want to deny people the right to work where they want. But the hypocrisy isn't confined to them. Some so-called libertarians (rightly) attacked New Labour for creating hundreds of new criminal offences but haven't been so noisy when the Tories continued this trend. Sure, true libertarians aren't guilty of this - but there are enough pseudo-libertarians to give the idea a bad name.

But there's something else. Opponents of libertarianism sometimes fail to see that freedom leads not to anarchy and chaos but to order. Demands for immigration control, for example, are often demands for government control in itself, because people don't see how uncontrolled processes can be welfare-enhancing. They fail to see how, in John Kay's words, our goals can sometimes be better achieved obliquely.

This habit is rooted in some common cognitive biases: the illusion of knowledge and overconfidence causes us to exaggerate the benefits of state control whilst the salience heuristic leads us to see the benefits of restricting freedom more than the costs. As Hayek said:

When we decide each issue solely on what appear to be its individual merits, we always over-estimate the advantages of central direction. (Law Legislation and Liberty Vol I, p57.)

But here's the problem. Sometimes, a benign spontaneous order doesn't occur. Emergent processes can sometimes produce inequality and exploitation: much depends upon initial conditions and institutional frameworks. If libertarians' critics overstate this, they themselves understate it.

All this might sound rather abstract, but it's not. It bears directly upon the question of how public services should be organized. Opponents of the part-privatization of the NHS see it as leading to profiteering, supporters as to more efficient service. Underpinning this disagreement are different attitues towards spontaneous order. Which is correct, though, depends on empirical matters such as market design, bidding processes and contract specifications. But then, when facts get ignored, tempers get heated.

May 14, 2015

The productivity challenge

If the Labour leadership election is anything like the General Election, it will be completely uninformed by sensible economics. This is to be regretted because there's one fact which - if it continues - must shape leftist politics, namely the stagnation in productivity growth. This is such an important issue that even the BBC can no longer ignore it (1'13" in).

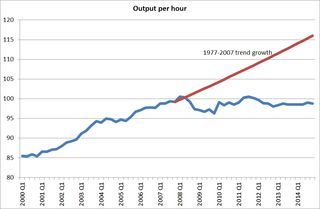

My chart shows the point. Output per hour is now 14.8% lower than it would have been if had grown since 2007 at the same rate as it had in the previous 30 years, of 2.3%. This is a massive gap - so much so that it is unlikely to have a single explanation. And we shouldn't expect it to be narrowed soon. The Bank of England yesterday predicted a pick-up in productivity growth but it foresees growth of only 1.7% in 2017 - below its pre-crash trend. And Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent warned that this forecast is "tremendously uncertain."

If productivity growth remains weak, it would have at least three political implications:

First, it means average GDP growth will be low. This is because it could only grow if employment expands. But the Bank is already worried that employment is so high as to threaten to raise nominal wage growth and hence inflation - which means that further incipient employment growth would lead to higher interest rates which would choke off growth.

This implies that the old assumption of both Tories and New Labour - that the economy would grow if only the right policy framework is in place - is mistaken. Supply-side policies - industrial policy if you like - are imperative. As for what these should be, there are many possibilities, including a more liberal immigration policy. I suspect we need a broad spectrum.

Secondly, if the economy's not growing much it becomes harder to fund public services; you can do so only by running a bigger deficit or by imposing higher taxes - and if real incomes are stagnating then resistance to the latter is likely to be severe.

Thirdly, stagnant productivity means that real income growth becomes a zero-sum game; workers can only see real wages rise if real profits fall, or one group of workers can only gain at the expense of others. In this context, raising "aspirations" would be a recipe for conflict.

All of this provides both challenges and opportunities for the next Labour leader.

The challenge is that Labour's traditional promise of funnelling cash towards health and education will be difficult to deliver.

The opportunity is that serious supply-side policies would offer something to all workers, not just the low-paid; this would be especially true if such policies include - as they should - greater worker ownership and control. Labour could claim that only it has a way of raising productivity and hence real wages; Owen is right - "aspiration" can be harnessed by the left.

The big issue in the leadership election should be how about these challenges and opportunities are addressed. I fear, however, that Paul Mason might be right, and the party lacks the intellectual resources to do so and what we'll get instead are empty words.

May 12, 2015

Wanted: a new Blair

Labour needs a new Tony Blair.

I mean this in a specific sense. In the 90s, Blair realized that the economy and society had changed and so old-style leftist and rightist policies were no longer relevant; one of the key texts of New Labour was entitled Beyond Left and Right, and Blair repeated the words "new" and "modern" not just as spin, but to emphasize that new times needed new policies.

This is what Labour needs to do now. I mean this in at least four senses.

First, there's the threat (to say the least) of secular stagnation, whereby a lack of monetizable investment opportunities mean slow trend growth in the west. This is manifesting itself in stagnant labour productivity - which means flat real wages.

This renders both Thatcherism and a bit of New Labour out-of-date. Both used to believe that the private sector would deliver growth if only governments could set the right framework; a small state in Thatcherites' case, policy stability in Brown's. In an era of secular stagnation, however, neither is sufficient (though they might be necessary). Governments need therefore to think more about how to promote growth. If "aspiration" has a sensible meaning, it means a set of policies to raise productivity and hence wages.

Secondly, the nature of inequality has changed. New Labour worried about the 90/10 ratio and thought that this could be narrowed by education and tax credits. Today, though, inequality is about the incomes of the 1%. Insofar as this is a problem - and I think it is - it needs different policies.

Thirdly, one relatively new feature of the economy is job polarization - the decline (pdf) of middling employment, a process which might be exacerbated by future (pdf) technical change. Combined with flat productivity, this means prospects for less-skilled workers are doubly bad as it means there'll be fewer middling-skills jobs for them to move into. This makes social mobility even less likely.

Fourthly, we now know something that left and right didn't know in the 80s and 90s - that there are severe limits on what managerialism can achieve. Increased power and income for bosses hasn't raised productivity in either the private or public (pdf) sectors, but has increased rent-seeking - a point which even rightists are coming to appreciate.

My point here is not to suggest a precise menu of policies to address these developments - though I suspect decentralized decision-making should play a big part. It is instead to say that we need to recognize today what Blair saw in the 90s - that the economy has changed and there is no point fighting old out-dated battles. I fear, however, that - paradoxically - some Blairites don't seem to appreciate this.

May 10, 2015

Mutual misunderstanding

The left and right don't understand each other's conceptions of morality, and don't even try to do so. This is the message I take from last night's row about Laurie Penny's reaction to the vandalism of a war memorial.

Laurie said:

What's disgusting is that some people are more worried about a war memorial than the destruction of the welfare state.

"Destruction" isn't entirely hyperbole. The Tories' proposed £12bn cut in welfare spending is equivalent to £45 per week per working age benefit recipient. That would impose horrible hardship upon many.

Instead, Laurie's mistake consists in doing exactly what Jonathan Haidt in The Righteous Mind accused the left of: she's seeing morality as comprising just one idea whereas the right sees others.

Haidt and his colleagues claim that there are (at least) five foundations of morality: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation. The left, he says, stresses the first two of these but underweights the last three.

And this is just what Laurie was doing. She was emphasizing the care principle, whilst being blind to the sanctity principle - to the idea that we believe that some things, such as vandalizing war memorials, are wrong because they break taboos even if they don't do material harm to anyone.

Now, there is, of course, a ton of hypocrisy surrounding ideas of sanctity. Many of those on the right who were outraged by the vandalism tell Muslims to tolerate cartoons of Mohammed and mock the left's preoccupation with political correctness and "safe spaces." And the left is sometimes deliberately transgressive of some norms whilst outraged by others: compare reactions to Richard Dawkins and Katie Hopkins. What's sacred and taboo to some is just nonsense to others.

Which brings me to the problem. Far too many - on left and right - are so wrapped up in their own narcissism and so quick to condemn others that they fail to understand (or even try to) where others are coming from: the virtue of Haidt's framework is that it facilitates such understanding.

What's being lost in all this is Mill's classical liberal idea - that there is a strong case for cognitive diversity. For me, Laurie's voice is a welcome contributor to this diversity. If the herdthink that rushes to condemn leads to her being more inhibited, something valuable will be lost.

May 9, 2015

"Aspiration"

Alan Johnson's lament that Labour is no longer "a party of aspiration" confirms my view that Blairism is not so much wrong as just out-of-date.

What I mean is that, back in the 90s, it was easy to be a party of aspiration. The IT revolution was promising a bright new future, so talk of aspiration, modernity and newness chimed with the zeitgeist. And the world economy was growing well and a favourable supply shock - a falling China price - was boosting real incomes. A government could thus deliver rising living standards simply by not screwing things up too much.

But now is not then. Labour productivity has been flatlining for years and the intelligent talk today is of secular stagnation, not of a new economy. This changes everything. In a world of zero productivity growth, people's real incomes can rise only in one of three ways: by moving from unemployment to work (which whilst a good thing is not what Mr Johnson means); or by getting a lucky supply shock such as falling commodity prices, which might not happen; or if one person's income rises at the expense of another's.

When productivity is flat, "aspiration" is a zero sum game.

This means that if Labour is to be a party of aspiration, it must do one or both of two things. Either it must shift incomes from profits to wages, say by embracing wage-led growth - which not Blairite and might not work. Or it must offer policies to raise productivity.

Now, there are many possible ways of doing the latter - albeit of perhaps dubious efficacy. But there's one worth emphasizing - greater worker ownership and control. There's good evidence (pdf) that this (pdf) can raise productivity, perhaps because it motivates people to work better, or perhaps because it makes better use of fragmentary, dispersed knowledge than central planners can.

This is why I say Blairism is irrelevant today. Back in the 90s, it was possible to be both a party of aspiration and a party of managerialism with its anti-egalitarian and pro-1% guff about "leadership". Today, this might not be possible, because the best hope for raising productivity and hence real wages lies in replacing managerialism with worker democracy."Aspiration" and radicalism might therefore be far more compatible than Blarities think.

May 8, 2015

The vision thing

It's always risky to take clear messages from election results.There's a danger of seeing what we want to see in what is in fact the outcome of a complex emergent process: as Scott Sumner says in a different context, there's no such thing as public opinion.

Nevertheless, I suspect that Paul Mason has a point when he says that this election has been a victory for those with a confident story. The SNP and Tories have done well whilst "Labour no longer knows what it is for, nor how to win power". The collapse of the Lib Dems fits this pattern. It had no message other than "umm, err we're not the nasty big boys" and won pretty much no support.

What Paul's saying is much like what I said yesterday - that parties must offer more than a shopping list for the median voter but also a cause worth identifying with - “the vision thing” or a narrative.

Put it this way. The SNP's actual fiscal proposals were much like Labour's. And yet it beat Labour massively. One reason for this, I suspect, is that it offered a strong anti-austerity message whereas Labour merely equivocated*.

This poses two questions. One is: what should Labour's vision be?

I agree with Paul Cotterill that it shouldn't be a "retail politics" in which managerialists "listen" to voters. As he says, doing so usually means listening to reactionary urges such as a clampdown on immigration and benefit claimants rather than to leftist ones such as the demand for more public ownership. And I agree that, on intellectual grounds, there is a strong case for "a new politics of organisation and production."

But there's a second question here: is it possible to combine both popularity and intellectual coherence?

One thing makes me hopeful - that this election was not a victory for austerity. The two main austerity parties - Tories and LibDems - saw their share of the vote fall by 14.4 percentage points whilst the two clearest anti-austerity parties (SNP and Greens) gained a combined 5.9 percentage points.

On the other hand, though, I'm pessimistic. Ukip's success* shows that there is also public support for anti-market policies: Ukippers (and indeed many other voters) favour (pdf) controls on prices and rents as well as on immigration. And whilst a slogan "we'll put you in control" should in theory be a popular and coherent way of promoting worker democracy, I see very little public demand for it.

It might, therefore, be very difficult for Labour to repeat its feat in the 1990s of finding a vision that's both intellectually credible and popular.

There is, though, another thing stopping it doing so. The party has so bought into managerialism that it seems not to have the intellectual resources to reinvent itself: a rehash of the Brownites vs Blairites "debate" is just irrelevant. As Paul M says:

Labour today is waking up to something much worse than failure to win. It has failed to account for its defeat in 2010, failed to recognise the deep sources of its failure in Scotland, and failed to produce any kind of intellectual diversity and resilience from which answers might arise.

* 12.7% of the vote is, sadly, some success: its lack of MPs owes more to the FPTP system than to its unpopularity.

May 7, 2015

Why I voted

On my way back from the polling station, I got caught in a heavy shower. This reminded me that, from the perspective of self-interested instrumental rationality, voting is irrational: the cost of doing so (getting wet) far exceeds the benefit, the infinitesimally small chance that our single vote will make a difference multiplied by the personal gains to us from our preferred candidate being elected.

However, millions of us today will ignore this thinking and turn out. This doesn't, I think, mean millions of us are so stupid we can't do basic cost-benefit calculations. It means instead that the instrumental perspective is a narrow one which ignores something important. But what?

One answer has been proposed by Andrew Gelman and Noah Kaplan (pdf). They say we have social preferences. When we vote, we don't just consider the benefit to ourselves but to others. And the tiny chance of a benefit to millions of people is big enough to outweigh the small cost of voting.

Another possibility - entirely consistent with that - is that we use what Robert Nozick has called (pdf) evidential expected utility (pdf). We think "if I vote then people who think like me are also likely to vote too which raises the chances of getting the candidate I want". Simon's right: collectively individually insignificant acts can be significant.

Both these theories are reasonable. But they run into a problem. It's hard to see how they can explain systematic differences in turnout. The young and poor are less likely to vote than the old and rich. Do they really have less social preferences? Are they less likely to use evidential expected utility - to be, in parlance of Newcomb's problem, one-boxers rather than two-boxers?

I doubt it. Instead, something else is happening. It's that there are many things we do not because they make sense in narrow cost-benefit terms, but because they symbolize the type of person we are. As Sam says, "voting isn’t instrumental, aimed at affecting policy, it’s expressive." It expresses an identity - who we are and (in my case and others) who we are not.

This, I think, contributes to explaining differential turnout. Older people were socialized into norms in which one did vote, often as an expression of class solidarity. With the decline of class-based voting, younger people have a weaker norm. And because none of our centrist managerialist parties try to speak for the worst-off, so many of the poor don't want to identify with them. As the IPPR's Matthew Lawrence says: "For many, democracy appears a game rigged in favour of the powerful and the well connected."

For me, this is another reason for voting Green. If the young and poor are to engage with mainstream politics - and it's moot whether the media-political establishment wants them to - then the parties must offer more than a shopping list for the median voter. They must embody a cause worth identifying with. And as Terry Eagleton says, the Greens are now the only party "unafraid of what George Bush Sr once called “the vision thing”". I have my doubts about that vision. But it represents a break from the managerialism of the main parties which has failed both to deliver good governance and to inspire the people. And I thus applaud it.

May 5, 2015

The voter turnout paradox

One of the many issues which hasn't had the attention it deserves in this election campaign is the paradox of voter turnout: the people most likely to vote are those with least at stake, whilst those least likely to vote have the most at stake.

I mean this in two ways.

First, the rich are more likely to vote than the poor; the IPPR has said (pdf) that in 2010 turnout in the highest-income quintile was 22.7 percentage point higher than that for the lowest quintile - implying that the rich are 35% more likely to vote than the poor. But the poor have (proportionately) more to lose than the rich. Any intelligent person on a six-figure salary should be able to afford the slightly higher taxes they'll pay under a Labour government without much discomfort. The policies that impose genuine suffering are benefit sanctions, the bedroom tax and the petty tyrannies of the DWP of the sort documented by the great Kate Belgrave. And this is not to mention the £12bn of unspecified benefit cuts planned by the Tories; these are equivalent to £45 per working age benefit recipient per week - a cut which cannot be imposed without huge suffering.

Secondly, the old are more likely vote than the young; in 2010, 74.7% of over-65s voted compared (pdf) to just 51.8% of 18-24 year-olds.

But again, the young have more at stake than oldsters. No main party plans to make big changes to pensioner benefits. But governments can greatly shape the lives of younger people, not least because youth unemployment can have long-lasting scarring effects upon future incomes, job prospects and health.

What explains this paradox? Why will I vote even though the election will make very little material difference to me whilst millions of my fellow citizens won't even though it does matter more to them?

I suspect that part of the story lies in Maslow's hierarchy of needs. We older, richer people have a higher demand for self-actualization than those who are struggling just to get by. We therefore want a government that doesn't too badly offend our sense of justice and propriety, so we take more interest in party politics than the poor who have more pressingly immediate material concerns.

This, though, isn't the whole story because, as the IPPR pointed out, turnout inequality is a relatively new phenomenon; it was small in the 1980s.What has also happened is what the IPPR calls a "vicious cycle of disaffection and under-representation" among the young and poor:

As policy becomes less responsive to their interests, more and more decide that politics has little to say to them.

What we're seeing is a form of learned helplessness in which people have resigned themselves to inequality.

Unequal turnout, though, surely matters not just because it undermines the democratic principle that citizens should have equal political power but also because it is itself a cause of material inequality; Sean McElwee points out that, in the US, "states with higher turnout inequality (more rich people voting than poor people) have higher income inequality."

So, what can be done about this? The IPPR recommends compulsory voting and Matthew Flinders advocates increasing political literacy. I'm not sure these are complete solutions. A few weeks ago Labour's Rachel Reeves said:

We are not the party of people on benefits. We don’t want to be seen, and we’re not, the party to represent those who are out of work.

If Labour has that attitude, doesn't benefit recipients' reluctance to vote become more understandable?

Perhaps we are reverting to the pre-democratic age, in which politics consisted of the rich debating among themselves how best to deal with the poor whilst the poor themselves were excluded from that debate.

May 1, 2015

"Serious" politics

My qualified endorsement of the Greens has led to some consternation: how can an economist endorse a party which has some fruitloop ideas? I suspect that some of this bemusement is a form of culture shock; it arises from the gulf between my perspective as an economist and that of Westminster bubblethink.

From my perspective, the main parties are just daft. They are promising to cut the deficit although this risks exacerbating any future slowdown and ignores the fact that negative real rates make this a great time to invest in infrastructure. They want to curb immigration even though there's no economic case for doing so and such curbs might hurt long-run growth. They are silent on the UK's single biggest economic problem, stagnant productivity and have no ideas about what to do about the banks beyond regarding them as a magic money tree; you'd never guess from the election debate that it was banks that caused the financial crisis. They have little solution to the housing crisis. And they seem to think governments can raise billions from reducing tax dodging without telling us which loopholes companies are using and which they intend to close.

In all these ways, the mainstream parties are as loopy as the Greens - and perhaps more expensively so given that macroeconomic errors can have a bigger cost than micro ones. As Martin Wolf says, none of them deserve to win.

Non-economists, however, don't seem to appreciate just how silly the mainstream is. A big reason for this, of course, is that the media has constructed its own narrative of mediamacro which legitimates deficit fetishism and "concerns" about immigration whilst marginalizing other issues such as the economic cost of inequality and stagnant productivity.

Mediamacro, however, is only part of the story. It is one of a number of practices whereby the ideas of those in power are given credence.

We see this, for example, in the way in which the media jealously guards its access to politicians to preserve the privileged dialogue of bubblethink - hence the hostility to Ed Miliband meeting Russell Brand. We see it in the way in which matters of choice are presented as necessities. We see it in the way in which some engagement with politics is approved and some (such as Milifandom) sneered at. And we see it in a host of legitimation rituals. These include the language of politics - who else uses phrases like "committed to", "pledge" or "the right thing to do"? - and even the dress code; Yanis Varoufakis is often called "unconventional" because he doesn't wear a tie.

Politics has many ways of creating and sustaining what Paul Krugman calls "Very Serious People" and Nassim Nicholas Taleb "empty suits" - men (generally men) whose judgments (always judgments) are sensible, sober, and wrong. One reason why I'll be voting Green is to reject this flummery.

Another thing: one might ask why there is no political party with entirely sound economics - one that: is concerned about productivity; anti-austerian; pro-market (in the right institutional framework); and egalitarian. But that's another question.

April 30, 2015

Why I'm voting Green

Next week, for the first time ever in a national election, I'll be voting Green. My main reasons for doing so are:

- The Greens are opposed to fiscal austerity. Labour's promise to "cut the deficit every year" unconditional on the state of the economy is a capitulation to mediamacro deficit obsession. Granted, they might well be insincere in this - but there's a danger that lies become the truth.

- The Greens (pdf) are more liberal on immigration. Sure they fall short of wanting open borders. But they don't celebrate their desire to condemn people to a lifetime of poverty merely because of an accident of birth, as Labour did with that notorious mug.

- I support the Greens wish to cancel Trident's replacement. I reckon £100bn could be better spent.

- I share the Greens' desire for a citizens basic income; I appreciate this isn't a manifesto commitment, but it should be the direction of travel.

- The Greens' support for a maximum wage is well worth discussion, not least because it recognizes that a more redistributive tax system isn't sufficient to reduce inequality.

- I suspect that the Greens are instinctively keener on civil liberties than Labour, and more antipathetic to managerialism.

All that said, there are some massive caveats. For example, I'm sceptical about some green policies; need more convincing (to say the least) about its attitude to banking reform and intellectual property; and don't like at all the party's instinctive antipathy towards free markets, as signaled by its desire for government spending to approach 50% of GDP*. Nor have I been impressed by Natalie Bennett's inability to sell even good policies.

There is, though, a bigger caveat. If I lived in a marginal, I would support Labour. For one thing, I very much want Ed Miliband to be our next PM, not just because this might rid our nation of the blight that is Katie Hopkins, but also because it would be a poke in the eye to the class-haters who have questioned whether he is prime ministerial enough. And for another, whilst Labour is hugely flawed, it is better than the Tories on, for example, on fiscal policy and benefit cuts.

However, I don't live in a marginal but in a massively safe Tory seat. My vote therefore has only expressive value, if only to myself. And I shall use it to express my disdain for how Labour has kowtowed too much to economic illiteracy and reactionary prejudice.

* Green policies might be described as "macro OK, micro bad" - but as James Tobin said, it takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers