Chris Dillow's Blog, page 101

April 29, 2015

A good election to win

This election could be an especially good one to win, according to some figures out this morning.

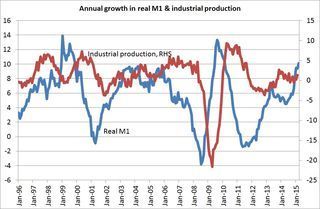

I'm referring to the ECB's numbers (pdf) showing that the M1 measure of the euro zone's money stock rose by 10% in the year to March, its fastest growth rate since May 2010.

My chart (source) shows why this matters. M1 - adjusted for inflation - has been a good leading of euro zone growth; accelerations in M1 growth in 1996, 1999, 2003 and 2009-10 all led to pick-ups in growth.

This could well benefit whichever party forms the next UK government, in two ways.

First, it should help reduce government borrowing. A stronger euro area economy gives us a chance of exporting more. It could also increase business confidence and investment here. On both counts, this should mean stronger domestic growth and hence tax revenues.

We can put this another way by thinking about financial balances. A healthier euro zone should help reduce the UK's current account deficit. That deficit is another word for foreigners' surplus. And if foreigners' financial surplus falls, UK residents' financial deficit must also fall: sectoral balances must sum to zero. This should mean a lower government deficit - especially if companies increase investment because of confidence about the euro area thus generating a corporate deficit.

Secondly, a stronger euro area economy will create jobs in the region - maybe lots of them if the euro area sees the same weak productivity growth as the UK and US. In a couple of years, therefore, the noblest prospect an unemployed Spaniard will see might no longer be the easyJet to London but the road to Barcelona. This could reduce immigration - not just because EU workers don't need to come to the UK to find work, but also because some non-EU workers will get jobs in the EU rather than the UK.

If the euro area does recover well, therefore, the next government will be able to say: "Look, we promised to reduce the deficit and immigration and we've done just that." Such a claim would be spurious, but post hoc ergo propter hoc seems good enough in politics.

Of course, there's a massive caveat here: given the unpredictability of recessions, we cannot be very confident the euro area will continue to grow. Perhaps a stronger inference, then, isn't that this is a good election to win but rather simply that the fate of the next government will depend in large part upon what happens elsewhere in the world. Which is something else that politicians aren't saying.

April 28, 2015

Economics for politicians

It's become a cliche to bemoan the fact that politicians are disproportionately Oxford PPEists. This is odd, as there's not much evidence that they read much E. Here are seven basic principles of economics that don't seem to be wholly grasped by the main parties.

1. Tax incidence. The burden of a tax doesn't necessarily fall upon the people who hand over the money. For example, stamp duty helps to lower house prices - which means that Labour's proposed cut for first-time buyers might just raise prices and so not help FTBers much. Similarly, a Mansion Tax would reduce the price of Mansions. That's a double blow for owners of mansions now, but it means that future owners won't be hurt; although they'll have to pay a tax, they'll buy their mansion cheaper. Also, in an open economy (pdf), it's likely that taxes on companies - in the form of a higher corporate rate or those unspecified anti-avoidance measures the parties like - will fall partly on labour insofar as the tax reduces investment.

However, incidence doesn't just matter for taxes. There's also benefit incidence. Housing benefit is in fact landlords' benefit because it raises rents. And welfare benefits help some firms as much as claimants: where do those benefits get spent?

2. Productivity growth matters. In the long run, it determines GDP growth. A party that was serious about wanting to improve living standards would therefore have a policy to raise productivity growth.

3. The knowledge problem. Any serious policy - in politics and in fact in life generally - must begin from the question: what do we really know? Politicians commonly overstate their knowledge. This leads to promises to cut government borrowing, even though this might not be feasible if economic growth slows. And it also closes off some interesting policy options such as the provisions of services through cooperatives rather than hierarchies.

4. The paradox of thrift. Efforts to save more or borrow less can be collectively self-defeating. To put this another way, falling government borrowing requires increased private sector debt. Oddly, the main parties don't seem keen to point this out.

5. Factor price equalization. Yes, foreigners might be forcing down British wages. But they don't need to migrate here to do so; international trade can bid down unskilled wages. The notion that immigration controls are sufficient to raise wages greatly is just wrong.

6. Deadweight costs.Labour wants to spend more on immigration controls.For a given (overly tight) fiscal policy, this is money and people diverted away from where they could do more good. That's a deadweight cost.

Another important deadweight cost is that of tax complexity; it leads to people looking for loopholes and gaming the system rather than doing proper work. Tax simplification (and benefit simplification too) should be a higher priority than it is.

7. Supply and demand. If you want to make houses more affordable, you do one thing: build more of them. Lefties might stress the importance of state action, righties the importance of liberalizing planning, Both, though, should agree that demand-side policies such as Help to Buy or cutting stamp duty are just daft.

I don't pretend this is an exhaustive list. I've confined myself to ideas on which economists broadly agree but which the main parties seem to reject. There is a big gap between politicians and economists.

April 24, 2015

The knowledge problem

Was Hayek merely a Cold Warrior who is irrelevant today, or does he still have something to teach us? I ask because of two things that have happened to me this morning.

First, I read Steven's observation that my scepticism about the efficiency of bonuses is consistent with the notion that bosses "simply lack the knowledge to run their firm effectively." Secondly, I fell into a conversation with a stockbroker who believes that he has the ability to spot fund managers who have the ability to beat the market.

Hayek is relevant to both issues. For me, his massively important insight is that individuals' knowledge is fragmentary and limited:

The knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate "given" resources...it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.

This led Hayek to argue for the superiority of competitive economies over central planning; the great virtue of the price system, he said, is that it makes best use of dispersed information.

If this were all, Hayek would be merely a historic figure - someone who was on the right side of history, but is irrelevant now.

But I don't think he is. The question he posed - what are the limits are individuals' economic knowledge? - still matters in at least two ways:

- If extensive knowledge is possible, then bosses might be able to manage big companies well. If not, then centrally planned companies will be inefficient. Sure, perhaps competition will eventually weed out egregious incompetence, but market forces might not grind so finely as to eliminate all inefficiency - and might even in some cases actually select in favour of quacks and charlatans.

- Should we trust fund managers with our wealth? If some people know better than the market, then maybe. But if individuals are less good at information gathering than the market, the answer is no. And the evidence (pdf) suggests no.

I'd add a third example. Labour's promise to "cut the deficit every year" is also a claim to knowledge. It just about makes sense if you know that the economy will grow every year. But this cannot be known; recessions are unpredictable and unpredicted.

There's a common theme in these three examples. The claim that individuals can possess extensive knowledge is also a claim to power and wealth; CEOs, fund managers and politicians all say: "trust us, because we know better."

In this sense, Hayek's message has shifted. Whereas it used to support dominant western institutions, it now undermines them. For this reason, it might be no coincidence that the question "what are the limits of our economic knowledge?" is rarely asked nowadays.

April 23, 2015

Bonuses & productivity

Big bonuses for bosses can have adverse effects upon productivity. A new paper by Jorg Oechssler, Anwar Shah and Nikos Nikiforakis concludes:

Managerial bonuses have the potential of generating conflict between managers and their subordinates. Managerial bonuses can be a disincentive for subordinates...firms should exercise caution when using high-powered incentives for managers. The benefits from managers’ increased motivation need to be weighed carefully against the adverse effects for other employees.

This is based upon laboratory experiments in which a manager and subordinate cooperate on a project: they found that when the manager is offered a big bonus, subordinates' effort levels drop.

This might well have external validity, given that in the real world managerial oversight of subordinates is less tight than it was in the lab. As HSBC's CEO Stuart Gulliver said, “Can I know what every one of 257,000 people is doing? Clearly I can’t.”

But of course, this is but one of several pieces of evidence that big individual bonuses can have adverse effects. Experiments (pdf) by Uri Gneezy and colleagues have shown that they can reduce performance because people can be over-motivated and so crack under pressure. Other experiments have found that bonuses for traders can encourage asset price bubbles, or that collective bonuses can reduce effort by encouraging free-riding. It's also possible that bonuses can crowd out intrinsic (pdf) motivations (pdf) and encourage short-termism and earnings manipulation. And Nobel laureate jean Tirole has argued that bonuses can cause "signifi cant efficiency losses" by over-incentivizing some roles and under-incentivizing others: traders tend to get big bonuses, risk managers not so much - so guess what happens?

I suspect that the main justification for bonuses is not so much that they elicit effort but rather that they are a form (pdf) of efficiency wage: bosses and CEOs who cannot be effectively monitored must be bribed handsomely not to steal the firm's assets.

Subject to this caveat, all this implies that bonuses can be inefficient. Insofar as they contribute to inequality, this in turn is more evidence that inequality might reduce productivity. How lucky it is for the rich, therefore, that our politicians don't care about productivity.

Another thing: if bonuses do reduce productivity, it's not obvious that the solution is to tax them more heavily; it could be that it's pre-tax bonuses that matter, to the extent that these are associated with individuals' sense of self-worth and intra-firm perceptions of fairness.

April 21, 2015

Heartless, clueless?

A leaflet from the Lib Dems sullies my doormat decrying "heartless Tories" and "clueless Labour", echoing Clegg's claim that the Lib Dems would "add a heart to a Conservative government and add a brain to a Labour one". This seems to me to be doubly wrong.

I don't believe the Tories are especially heartless. I suspect Michael Gove was sincere in wanting to improve the education of the worst off, and I even suspect Iain Duncan Smith really does want to reduce poverty; he's just gone about doing so cackhandedly.

In fact, in many ways, the Tories have been brainless: imposing a costly and unnecessary austerity; shambolic welfare reform;a non-existent foreign policy; and a daft promise to cap immigration, to name but a few.

Equally, though, the implication that the left is all heart is also dubious. Labour's demand for immigration controls is a heartless attack upon the poor. And I suspect that many leftists use identity politics as cover for brute careerism.

Hearts and brains are bi-partisan; they are spread across the political spectrum - as is their absence.

However, the Lib Dems aren't proposing this false dichotomy merely because they are a party without principle who can only define themselves by what they are not. The "cruel right" and "silly left" are old prejudices. In 1988 Alan Blinder wrote a book Hard Heads, Soft Hearts in which he tried to combat that distinction. And in 1996 Tony Blair complained of the longstanding but "foolish" tendency to regard Tories as "cruel but efficient" and Labour as "caring but incompetent."

I suspect these prejudices reflect two errors.

One is a form of naive cynicism which regards inequality and injustice as natural and inevitable, and so attempts to fight it must be futile and foolish whilst defenders of the system are hard-headed realists.

The other is a tendency to underweight the incompetence of those who are on the side of the rich.

Hostile portrayals of capitalists have for decades been of Gradgrindian figures grinding the faces of the poor rather than of bumbling oafs. And today bankers are routinely described as greedy when in fact what distinguishes them from the rest of us is their stupidity: most of us like a pound, but we didn't destroy an entire industry.

What this misses is the likelihood that a lot of success in business might be due to dumb luck.

In this sense, the claim that the the rich are heartless, by understating their stupidity, actually helps to legitimate inequality.

April 17, 2015

Note on Laffer curves

Tim and Richard have been having an argument about Laffer curves. Here, in no particular order, are my notes on the matter.

1. There are (at least) two Laffer curves - one that relates top tax rates to GDP, and on that relates them to tax revenues. The two probably do not coincide. For example, if a top earner responds to higher taxes by continuing to work but by dodging tax, GDP is unaffected but revenues fall. For this reason, the revenue-maximizing top rate is probably lower than the GDP-maximizing rate. To this extent, Richard is right to stress the importance of tax dodging. As Alan Manning says, a rise in the top rate must be accompanied by efforts to reduce avoidance and evasion. (Film tax relief has always struck me as an invitation to conmen.) Given that the deficit doesn't much matter, I would rather we thought more about the effect on GDP than on revenues.

2. Even if high top tax rate do reduce incentives, this needn't be a bad thing. They disincentivize rent-seeking, office politics, exploitation and negative externalities such as risk pollution as well as productive activities - maybe more so, given that the intrinsic motivations to engage in the latter are greater.

3. We should distinguish between incentive effects upon employees and the self-employed. The former might well be trivial: if someone stops working because of high taxes, his employer will replace him. The latter might not be.

4. There's very little robust UK evidence here, simply because the top tax rate didn't change for years. And it's hard to infer anything from the rise in the rate to 50% in 2010 because of forestalling and because the rate didn't last long enough to have longer-term behavioural effects.

5. The shape of the Laffer curve depends upon tax morale. if you think taxes are theft, you'll try and dodge higher ones or stop working. If you think they're the price to pay for living in a civilized society, you'll accept them. This implies that the revenue-maximizing tax rate will vary from time to time, place to place and people to people. For this reason, even good international (pdf) evidence might not be a good guide to tax-setting in the UK. The first two of Kling's laws apply: sometimes it’s this way, and sometimes it’s that way; and the data are insufficient.

6. Relevant evidence here also comes from laboratory experiments. Some of these suggest that a 50% tax rate maximizes revenue.

7.As Tony Atkinson says, taxes might not be sufficient to reduce inequality. One reason for this is that pre-tax inequality also matters.

8. There are two contrary but tenable positions here. One is "the revenue-maximizing tax rate might be high, but high taxes are undesirable because they infringe freedom." The other is "The revenue-maximizing tax rate could be low, but high taxes are justified to reduce the adverse effects of inequality." Both of these positions are rare - which makes me suspect that there's quite a lot of motivated reasoning on both sides.

April 16, 2015

Forecasting vs explaining

There's a big difference between forecasting and explaining. This is one point which I fear is being under-emphasized in the culture war about the state of macroeconomics.

Critics often infer that the discipline failed because it didn't foresee the crisis.

It's certainly the case that few people saw the crisis coming. For example, only one forecaster of those surveyed by the Treasury in March 2008 foresaw a fall in GDP in 2009 - and he had also, wrongly, forecast weak growth in 2005 and 2006. UK economists weren't alone here: US forecasters also failed to see the recession coming, as did those in other countries.

Nor even was the failure confined to the Great Recession. Back in 2000, the IMF's Prakash Loungani wrote that forecasters' failure to foresee recessions was "virtually unblemished."

This tells us that the failure to predict recessions was not confined to DSGE models. Forecasters use a variety of methods, including a heavy dose of judgment. Pretty much all these methods failed.

I'm not sure that heterodox economists did much better. Steve Keen's Debtwatch focused mainly upon the Australian economy which did not suffer a recession in 2009. And even Wynne Godley didn't do much better than others. In April 2007 he wrote (pdf) of the US:

output growth slows down almost to zero sometime between now and 2008 and then recovers toward 3 percent or thereabouts in 2009–10.

That's better than most, but still some way off.

Does this near-universal failure tell us that macroeconomics is useless? Maybe not. Perhaps there's another explanation. Maybe recessions are just not predictable at all. The 2009 recession originated, to a large extent, in a micro failure, not a macro one - the collapse of banks. This is consistent with Xavier Gabaix's vew that recessions have granular origins and with Acemoglu's theory that they are propagated by network effects.It could be that the economy is so complex that forecasting is, as David says, just a mug's game*.

Many of macro's critics are begging the question: they are assuming that the economy could be predictable, if only we had a good enough theory. I doubt this**.

Now, this is just a hypothesis - albeit one consistent with lots of evidence. If you want to show I'm wrong, point me to some forecaster who foresaw both the recession of 2008-09 and the growth either side thereof. Or, failing that, show me forecasts for future years which successfully predict both growth and recessions.

It's not good enough to say "macro failed to foresee the crisis, therefore we need a new theory." Come up with the theory, and test it against the data.

Nor is it good enough to simply point to the risk of recession. Forecasting a recession that doesn't occur is as bad as not forecasting one that does; both lead policy-makers to make bad policy and investors to make bad asset allocation decisions.

We should not, however, infer that just because macroeconomic forecasting is impossible (at least, given the present state of our knowledge) that we are at the mercy of crises. At least two pieces of economic knowledge would have protected investors from the 2008 crisis, both of which were available at the time:

- the tendency for foreign buying of US equities to predict annual returns: this hit a record in 2007, warning us of trouble.

- the seasonality of the stock market. "Sell in May, buy on Halloween" would have gotten you out of the market well before Lehman's collapsed - albeit at the price of missing out on some of 2009's recovery.

Of course, these two hypotheses told us nothing about banks, debt, real GDP or monetary policy. But this tells us two things: that economics can be useful even if macro is not; and that there's a big difference between explanation and prediction. As Jon Elster said:

Sometimes we can explain without being able to predict, and sometimes predict without being able to explain. (Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, p8)

Macroeconomics - when done well, which is only some of the time - does the former. This might be all that can be expected.Whatever else is wrong with macro theory, the inability to foresee recessions is not the problem.

* Macroeconomics is not unique here: Gene points out that, for everyday purposes, the natural sciences lack predictive power too.

** I don't think we have good enough data either, but that's another story.

April 14, 2015

The problem with promises

"He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster." Labour's manifesto reminded me of these famous words of Friedrich Nietzsche.

It begins thus:

A Labour government will cut the deficit every year. The first line of Labour’s first Budget will be: “This Budget cuts the deficit every year.”

This is, of course, silly. It amounts to a promise to tighten fiscal policy even if the economy weakens. The statement could be rewritten: "if a recession occurs, we'll make it worse."

Granted, few people expect a recession in the next five years. But this means little. Recessions are unpredictable - or at least unpredicted.Any sensible economic policy would take into account the risk of bad times. Labour's doesn't.

You might object that recessions could be offset by monetary policy instead. I'm not sure. A rough and ready calculation shows the problem.

The OBR's current forecast is for the output gap to narrow from 0.6% now to zero by 2019*. However, its data show that the standard deviation of the gap since 1973 has been 2.2 percentage points. So let's assume that a shock of this magnitude happens. The OBR estimates (pdf) that this would increase government borrowing by 1.1 per cent of GDP through normal automatic stabilizers. To cut the deficit every year in the face of this incipient increase thus requires a discretionary fiscal tightening of 1.2 percentage points. How much monetary loosening would be necessary to offset this?

Obviously, it depends upon the size of the fiscal multipliers. Let's call these one. We'd then need a monetary stimulus sufficient to raise GDP by 3.4%: 1.2% to offset the fiscal tightening and 2.2% to close the output gap.

Now, the Bank of England estimates that the first £200bn of QE raised GDP by 1.5 per cent. Simply scaling this up implies that we'd need £450bn of QE to raise GDP by 3.4%. This would take total QE to £825bn.

I reckon this is errs on the low side. For one thing, my assumption about multipliers might be low given that these are bigger (pdf) in recessions and at the zero bound. And for another, QE was probably more effective in 2009 than it would be now because gilt and corporate bond yields back then were higher.

I'm not sure this is attractive. It's would mean nationalizing more than half of government debt. And - given that QE raises asset prices - it has distributional effects which Labour supporters might not like.

Granted, there might arguably be more effective forms of monetary ju-ju such as raising the inflation target or green QE. But Labour's manifesto, as far as I can see, is silent on these.

Labour's promise to cut the deficit is, therefore, not a sensible one. Deficit reduction should be contingent upon the state of the economy.

It is, though, easy to see why they have made it. The party is simply bowing to the economically illiterate demands of mediamacro and bubblethink. When much of our ruling class - the coalition and the media - is stupid, then acting stupid yourself might be the best option.

Herein, though, lies my problem. I like to think that this promise is just a lie - that if the economy does weaken, Labour would claim force majeure and abandon it.

But there's a danger here. In Influence, Robert Cialdini describes how some Americans who were captured (pdf) by the Chinese during the Korean war were asked to make pro-Communist statements.Many of those who did so subsequently collaborated with the Communists to a greater extent than necessary. This, says Cialdini, shows that we have an instinctive desire for consistency. Having made a statement under duress which we believe to be false, we go onto behave in a way consistent with it.

In the same way, Labour's promise, daft as it is, might actually constrain their future behaviour. People who act stupid might become stupid.

* The output gap is a nonsensical idea, but let's suspend disbelief.

April 10, 2015

A positive Conservative agenda

The anti-Miliband campaign seems to have backfired: it's created an image of someone who is both weak and ruthless and a nerd and a shagger - which betokens a certain confusion.

Some on the left, though, believe the Tories have had no option but to use such negative campaigning. Phil says:

When your coming manifesto promises little more than demented and unnecessary cuts, a possible EU exit, and precious little else the Tories have already lost the politics.

This poses the question: what might a more positive Tory platform look like? If I were Cameron, I'd stress three elements.

First, I'd make more of a virtue of smaller government. I'd claim that this isn't merely a byproduct of austerity, but an end in itself. For example, I'd point out that cuts can increase government productivity: the ONS estimates that the output of government services has risen despite lower manpower. I'd also argue that smaller government can increase growth, perhaps - in the longer-run - by fostering a culture of self-reliance.

One element of this should be greater civil liberties: if you're going to cut police numbers, you must give the remaining coppers less to do. Here, the coalition has missed a trick. Many of us resent the increase in criminal offences under New Labour. Rather than reverse this, however, the government has continued the trend.

Secondly, I'd revive interest in happiness policy and the Big Society: the two are related, because strong social networks improve well-being. In this context, the promise to give paid leave to do voluntary work is a good idea. But rather than offer it as a gimmick, it should be part of a narrative; volunteering improves well-being and might even have an economic payoff too.

Thirdly, I'd adopt the "blue-collar conservatism" of Ruth Davidson of Robert Halfon, which directly addresses questions of workers' living standards. This might include tax credits for firms that pay living wages and, as Mr Halfon, has suggested, greater support for trades unions. These are the "little platoons" of which Edmund Burke approved, and can be a more efficient alternative to unwieldy and inflexible labour laws. It could also include tax breaks to encourage worker ownership: "popular capitalism" is a feasible Tory slogan.

All this would, I reckon, help defuse Labour's strengths - that the Tories are the the "nasty party" on the side of the rich. It would give substance to Danny Finkelstein's claim this week that Labour doesn't have a monopoly on decency.

Of course, many of you will claim - with reason - that such an agenda has its faults. But it is surely more coherent than mere prating about the nation's credit card, and more attractive than personal attacks.

So, why aren't we hearing more about it?

One possibility is just incompetence: the Tories have imported Lynton Crosby's negative campaigning tactics from Australia without considering whether they will work here. Another possibility, though, is structural.Perhaps the Tories have been so captured by plutocrats and big-staters that they have forgotten that there could be a decent conservatism.

April 9, 2015

Happiness policy, & growth

There's a lot that we've not seen so far in this election campaign. One of the many absences has been any discussion of happiness policy. This is odd, given that back in 2006 Mr Cameron said:

Improving our society's sense of well-being is, I believe, the central political challenge of our times.

You might that the financial crisis overturned this belief. Perhaps it shouldn't have, because well-being might be one solution to slow growth. Some new research claims:

Average local happiness is positively correlated with both R&D intensity and firm investment after controlling for firm and local area characteristics.

To me, this seems intuitive; happier people are more likely to be optimistic, and optimism - animal spirits - raises investment.

This, though, is only one of several channels through which higher well-being might boost economic growth:

- Research by Alex Bryson and colleagues has found that "workplaces with rising employee job satisfaction also experience improvements in workplace performance." This corroborates a finding by Daniel Sgroi.

- People who have good social networks - which are a major contributor to happiness - are more likely to find work quickly and have better job matches.

- There's a strong correlation between happiness and trust. And higher trust means higher economic growth - because trust can overcome market for lemons problems and also encourage lending and investment.

These mechanisms suggest that policies that increase subjective well-being - such as ones to improve job satisfaction, social capital and inter-personal trust - might also increase economic growth. As Charles Kenny has written (pdf):

Actions that improve happiness and the strength of social interaction are good in their own right and might have the added advantage of encouraging growth.

This is an example of John Kay's obliquity: we can sometimes achieve one objective by striving for another.

This, of course, would be a futile observation if policy were unable to increase well-being. But perhaps it can. A report by the Legatum Institute has suggested several possibilities: better mental healthcare; encouraging parents and schools to nurture soft skills;encouraging voluntary work; ensuring that the built environment encourages sociability;creating full employment; and empowering people in work and in politics.

Of course, you can be sceptical about each individual observation here. For example, Ben Southwood has suggested that the correlation between happiness and investment might be due to an omitted variable; IQ, for example, would raise both.

However, I suspect that risk-reward considerations favour happiness policy. In the best case, it might boost growth - and given the threat of secular stagnation we need all the help we can get. But in the worst case, little harm is done. In this sense, happiness policy could be close to a free hit.

Which poses the question: why isn't it on the agenda?

I suspect that it's for disreputable reasons. Happiness policy looks like gawd-help-us soppiness. It's therefore inconsistent with the image of macho managerialism of "tough choices" and "strong leaders" which our politicians want to project - and which our vile philistine media demands.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers