Chris Dillow's Blog, page 102

April 7, 2015

Diamonds or fool's gold?

Are the rich diamonds or are they fool's gold? I ask because of something Tim says. He responds to George Monbiot's complaint that:

There is an inverse relationship between utility and reward. The most lucrative, prestigious jobs tend to cause the greatest harm. The most useful workers tend to be paid least and treated worst.

This, says Tim, is just an example of the old diamond-water paradox. Diamonds (usually) have a higher price than water because they have a higher marginal utility and are scarcer than water.

This, however, obscures a vital question: what exactly is the source of the high marginal utility of people on mega-salaries to their employers? Is it because such people are genuinely useful, or is it because they are lucky but useless? Hence my question: are they diamonds or fool's gold?

First, we should distinguish between social and private utility. A CEO, for example, might be tremendously useful to his shareholders but not to society if he increases profits by creating externalities - if, for example, a mining company destroys the local environment.

An important set of cases here is risk pollution. Banks, for example, make money for their senior staff (if only rarely shareholders) by taking on extra risk in the knowledge that, if things turn bad, taxpayers will partly bear these risks. Banks, in effect, get a massive subsidy from the taxpayer.

Secondly, perceived marginal utility, and hence demand, is in part an ideological construct. Imagine a society in which remuneration committees thought: "Corporate growth is largely random and bosses have very little foresight into how their strategies will work. There's no point therefore paying CEOs millions. All we need is a competent administrator paid a respectable professional salary." And imagine this belief coexisted with the idea that people must have dignity in old age and that only a few care workers (to take George's example) have the personal skills to enhance that dignity. In such a world, care workers would be more highly prized. Wage differentials between the CEO and care worker would thus be modest.

What's more, there can be lower-level market failures which create big demand and hence high salaries even for failures:

- Werner Troesken has shown that demand for quack (pdf) remedies in the 19th and early 20th centuries was strong. He says: "Patent medicines proliferated and flourished not despite their dubious medicinal qualities, but because of them”. One reason for this was that quacks invested massively in product differentiation. The failure of one remedy did not therefore discredit the industry but merely shifted demand towards others. I suspect the same thing is true for CEOs and for fund managers: under-performance by one (or many) merely leads to a search for the superstar who can succeed.

- Marko Tervio has shown that what employers want is not talent but proven talent. This, he says, serves to greatly limit the supply of suitable workers, with the result that mediocrities with some kind of track reord get big money: film stars or CEOs fit this model.

- Bjorn-Christopher Witte shows how competition between fund managers can sometimes encourage reckless risk-taking with the result that lucky chancers will thrive. For example, in the early 00s bankers who danced to the music and took risks got big bonuses whilst those who sat it out got sacked. And during the tech bubble money flowed to those managers who thought boo.com and Baltimore Technologies were good stocks, whilst sceptical fund managers such as Tony Dye were fired.

- Hedge fund managers can, in normal times, generate good returns and fees merely by artlessly taking on tail risk - as in Andrew Lo's example (pdf) of Capital Decimation Partners. In fact, non-financial bosses can also "succeed" by taking tail risk - for example by under-investing in R&D, IT or maintenance.

My point here is a simple one. Appealing to demand or marginal utility does not suffice to explain or justify high salaries. Instead, we must ask: what is the source of that marginal utility? Once we ask this, we can see that George's claim that many of them are in fact parasitic kleptocrats might be more consistent with orthodox economics than Tim (or indeed George) appreciates.

April 6, 2015

Fear of freedom

Today is pensions freedom day, which has led to fears that people will misuse their freedom and so pay too much tax, stoke up a buy-to-let bubble or just spend too much too soon and so end up in poverty.

This reminds us that freedom is a scary thing. Bryan Caplan highlights some words of Martin Luther:

I frankly confess that even if it were possible, I should not wish to have free choice given to me, or to have anything left in my own hands by which I might strive toward salvation. For, on the one hand, I should be unable to stand firm and keep hold of it amid so many adversities and perils and so many assaults of demons, seeing that even one demon is mightier, than all men, and no man at all could be saved; and on the other hand, even if there were no perils or adversities or demons, I should nevertheless have to labor under perpetual uncertainty and to fight as one beating the air, since even if I lived and worked to eternity, my conscience would never be assured and certain how much it ought to do to satisfy God.

This is a very modern passage. Just as Luther feared that free will would lead us to fall short of the standards demanded by God, so we moderns fear that it will cause us to fall short of the standards demanded by rationality. And Luther, like us, fears the uncertainty that freedom brings.

I suspect that these fears are exacerbated by a couple of errors.

One is that we fail to appreciate that freedom often leads not to anarchy and chaos but to spontaneous order. As I've said, it's no accident that people who most want immigration controls also tend also to want state intervention in other areas of the economy - because they under-rate the power of the invisible hand.

A second mistake, which is more relevant to pensions freedom, is the failure to empathize sufficiently. This can lead us to be too quick to see irrationality in others.

For example, it might be quite rational to spend a lot of money early in our retirement. Doing so can build up a stock of happy memories which we can look back upon in our dotage. Some types of spending are in fact like saving; the give us a source of happiness in future years. And it makes sense to spend whilst we still can. The marginal utility of consumption declines (pdf) as our health deteriorates; holidays are less fun if we can't walk far, and nice cars are useless if our eyesight has gone. It's possible to be too prudent, and to save too much.

Sure, some neoclassical economists are prone to see rationality everywhere, even in destructive behaviour such as addiction. But behavioural economists can be prone to the opposite error; they are too quick to see irrationality.

However, it is not just others' freedom that we are scared of. Perhaps, like Luther, we are also scared of our own. I've recently been thinking of retiring. One reason why I haven't done so is that I'm scared that I might be misjudging my future finances; the uncertainty here isn't just the risk surrounding financial returns but the unquantifiable uncertainty about my future tastes. So far, this fear has been stronger than the countervailing fear, that I'll lie on my deathbed regretting that I have wasted my life by working.

The limits upon our freedom are not just those imposed by laws. There are also what William Blake called "mind-forg'd manacles." Fear - be it the fear of uncertainty or of others' opinions - is also a constraint.

April 2, 2015

Some election non-issues

I said yesterday that there are many questions which aren't big election issues but which should be. Here, in no particular order, is a list of some:

1. What, if anything, can be done to raise productivity (pdf)?

2. Is our big external deficit a sign of worryingly high domestic borrowing, or is it rather due to the overseas savings glut?

3. Given that work makes people more miserable than pretty much any other activity, what (if anything) can be done to improve (pdf) job satisfaction?

4. Should we raise the inflation target, or lower it?

5. What should be the mix of fiscal and monetary policy? Labour is offering us a less tight fiscal policy. For a given inflation target, this implies a less loose monetary policy. Is this a good thing or not?

6. Is the financial sector too big, perhaps because it diverts talented people from other occupations or is a source of instability? Or is it instead the industry in which the UK has a comparative advantage?

7. Are there good positive arguments for a sustained smaller state, or is this merely a by-product of fiscal austerity?

8. Is wage-led growth really a feasible way of boosting trend growth?

9. Are we in an age of permanent secular stagnation? If so, what can governments do to combat it?

10. Is privatization of some NHS services really just a way of enriching the private sector, or could competitive tendering, properly organized, improve NHS productivity?

11. What's the best way of protecting workers from exploitative conditions? Is it legislation, or strengthening workers bargaining power through a tighter labour market and stronger unions?

12. Is hierarchy really the best way of structuring public (and private!) organizations? Or has managerialism been pushed too far, with the result that we are losing the benefits of cognitive diversity and the best use of dispersed, fragmentary knowledge?

13. Given that there's reasonable evidence that worker ownership can raise efficiency as well as happiness, should governments do more to encourage it? If so, what?

14.Is the rise in wealth and power of the 1% since the 1980s a problem - in economic or social terms - or not? If so, what to do about it?

I don't pretend this is a complete list: it's confined only to economics. In some cases - such as questions 12-14 - there are obvious reasons why these are not on the agenda. But in others, the silence is less easily explicable or justifiable. And I'm not sure whether the fault lies with politicians, the media - or voters.

March 31, 2015

The other deficit

I suspect there's a long list of things which are not election issues but which should be. On this list should be: what to make of the fact that the UK's current account deficit last year was 5.5% of GDP, the biggest peacetime deficit since at least 1816*?

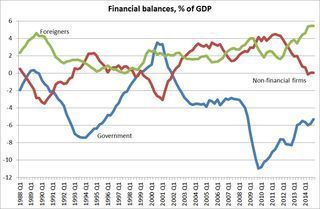

First, let's put this into a context. One of the big developments of recent years has been the near-disappearance of the non-financial corporate sector's financial surplus. Since 2011, it has fallen from £69.9bn to £1.1bn, its lowest level for 14 years. This could be tremendously good news. It means that capital spending has risen relative to retained profits - which could be a sign that the dearth of investment opportunities is fading.

However, there's one notable effect this hasn't had. It hasn't led to a big decline in government borrowing.

The point here is simple. Financial balances MUST sum to zero: if one sector is a net lender, another muct be a net borrower. In the past, swings in the corporate sector's surplus have been mirrored by swings in the government's deficit. For example, corporate surpluses in the early 90s and late 00s were accompanied by government borrowing, and corporate deficits in the late 80s and late 90s were accompanied by government surpluses. To put this in more familiar terms, strong capital spending means a strong economy and hence buoyant tax revenues.

However, the fall in the corporate sector's surplus recently hasn't greatly reduced government borrowing. Instead, its counterpart has been an increase in the current account deficit: as the UK domestic sector (which includes households and financial companies as well) has gone from surplus to deficit, foreigners' financial surplus has risen.

Hence the question I began with: what to make of this?

One possibility is that this shows that the UK lacks capacity in tradeable goods and services. As capital spending and hence economic activity generally has picked up, we've sucked in imports. Our incomes have, in effect, leached overseas rather than to the taxman.

One could therefore argue that we do indeed have a structural government budget deficit, in the sense that there's a big deficit even when the private sector is running a normal financial balance.

This provides a better justification for a tight fiscal policy than the Tories are offering. Such a policy means - given the inflation target - a low path for interest rates which should weaken sterling and so boost competitiveness; think of the standard Mundell-Fleming story. Sadly, this argument is weakened by the Meese-Rogoff puzzle. But one could revive it: to the extent that the external deficit/foreigners' surplus is the counterpart of the government deficit, maybe austerity is needed to reduce the current account deficit and so prevent a disorderly adjustment in which sterling collapses.

There is, though, another interpretation. Maybe the exogenous variable is foreigners' desire to save - due to the Asian savings glut and government and private sector retrenchment in the euro area. If foreigners want to save, someone has to borrow. And that someone has been the UK government.

Financial markets seem to believe its the latter: falling index-linked yields and a strong pound tell us as much.

Which brings me to a hunch. This might be changing. Signs of a recovery in the euro area have been accompanied by a fall in the UK's trade deficit, the biggest part of our current account deficit. This could mean that the foreign sector's surplus is falling. If this happens as the same time as the domestic sector continues to run a deficit, then the government deficit will shrink.

Given that what passes for economic policy debate is often just an application of the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, this might mean that the next government - whoever it is - will be able to claim success in reducing borrowing.

* Based on B.R.Mitchell's British Historical Statistics. Data since 1830 are in this Excel file from the Bank of England.

March 29, 2015

Competition & working conditions

Tyler Cowen argues against (pdf) Elizabeth Anderson's view (pdf) that capitalist bosses exert oppressive power over workers and, implicitly, against my view that capitalist work is alienating. This, I suspect , is one of the many issues in the social sciences where both sides are right to some extent.

Tyler is right that competition for workers can drive up working conditions, and it is surely true that those conditions are vastly better in the west now than they were in the early days of the industrial revolution.

Nevertheless, I fear that Tyler might be claiming too much.

First, though, some facts. The evidence that capitalist work is oppressive doesn't consist merely in extreme cases of bosses' tyranny. Alex Bryson and George MacKerron have measured people's experienced happiness during 39 different activities, and found that paid work comes 38th of 39; only being ill causes more unhappiness.

This is consistent with the unemployed having lower life-satisfaction than the employed. Life-satisfaction is a different thing from experienced utility. It consists (in part) in having a role in life and being unemployed removes a source of this role - even though it is painful to fulfill it.

I reckon there are four reasons why the mechanisms Tyler describes aren't strong enough to sufficiently improve the working environment.

The most obvious is mass unemployment. Even after years of recovery, the wider measure of US unemployment is still high, at 11% of the workforce. And in the UK on top of the official 1.9m unemployed there are 2.2m "inactive" wanting a job and 1.3m part-timers wanting full-time work. That's a total of 5.4m or one in six of the labour force. This means that the labour market is a buyers' market, which allows many employers to drive down standards or at least not worry sufficiently about improving them.

Secondly. I fear that Tyler is under-rating the importance of job-specific human capital. We know that this is widespread simply because workers who lose their jobs earn less (pdf) when they return to work. This in turn means that workers lack bargaining power to get better conditions because they are locked into their employer. This might help explain one of Bryson and MacKerron's findings - that better-paid workers are no happier in work than worse paid ones. It could be that such workers, having more job-specific human capital, feel that they lack bargaining power.

In this context, perhaps Tyler (and everyone else!) is misdescribing monopsony. Maybe monopsony is a feature not so much of firms but of transactions: a firm might have monopsony power with respect to workers with job-specific human capital, but not with respect to those with more portable skills*.

Thirdly, the wheels of competition don't grind very finely. Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen show (pdf) that there is a long tail of badly managed firms. If competition doesn't drive out bad management, why should we assume that it drives out poor working conditions?

A final problem is one of a lack of ecological diversity. Imagine if most countries in the world were communist dictatorships in which people were free to emigrate. Competition to retain people would alleviate the harshness of government. But nobody would pretend that it maximized well-being, simply because of the lack of attractive alternative governments.

Maybe a similar problem afflicts capitalism. Managerialism, short-termism, hierarchy and theory X are so widespread that it's hard to escape them: for example, Marina Warner's complaint about managerialism in universities applies to many universities, not just to one or two.

Now, it might be that there is nothing much that can be done to lessen the alienating and oppressive elements of capitalism: maybe work really is Adam's curse. But we should at least investigate this question. Although I disagree with Tyler about the extent to which there is a problem here, I have a much stronger complaint against those who don't even want to consider the issue - which includes pretty much all politicians.

* A caveat. Job specific human capital might create a bilateral monopoly; the firm needs the workers' specific skills as much as the worker needs the firm. I suspect, however, that in many cases the firm's second best option is better than the worker's, which gives the firm bargaining power.

March 26, 2015

The Clarkson problem

Imagine if Ant and Dec had racially abused a colleague before lamping him. Would there be a big political campaign and a million-strong petition to save them? I'm not sure. This tells us that Clarkson's popularity isn't based solely on the fact that he's a talented TV presenter.

Equally, though, I'm not sure that its due simply to the fact that he is (or plays at being) an obnoxious racist bully; whilst he has the support of many prominent arseholes, his popularity isn't confined to bigots.

Instead, I suspect James is right: Clarkson is popular because he's a "rebel." When he uses words like "slope" or "nigger", his supporters don't cheer his racism but the fact that he's rebelling against then"PC brigade." Many men believe as Bruce does: "we are not allowed to think or say what we want to any more, the thought police have taken over." To them, Clarkson is a hero not because of his racism so much as his fighting for freedom.

How did we get into a position where a millionaire public school racist bully can be seen as someone who speaks for the underdog?

There are two things going on. And I don't like either of them.

One is white male resentment - a tendency for some men not to see their privilege and instead to wallow in a fictitious victimhood.

But on the other hand, there is a big dose of illiberalism on the left - seen, for example, in its policing of language; the urge to ban things; and in New Labour's creation of thousands of new criminal offences (something which the coalition continued). And there is a particular type of careerist who uses feminism and "political correctness" to sustain their own narcissistic self-righteousness and ambition: for example, when Greg Dyke complained that the BBC and then FA were too white, he did not see either as a reason to resign himself in favour of a black person.

These twin positions are in danger of crowding out a third. This is a leftism which believes in free speech - which accepts (grudgingly) Clarkson's right to use retrograde language but also others' rights to call him a cunt for doing so: a leftism which worries about real, substantive inequalities more than about language; and one which wants not so much to get women or right-thinking men into positions of power and wealth but rather to abolish such positions.

In these ways, the Clarkson affair has highlighted the poverty of much political discourse.

March 25, 2015

Alienation: the non-issue

Matthew Syed in the Times gives us a wonderful example of Marxist thinking. He asks why marathon running is so popular, and says it's because it satisfies a desire for self-improvement which we cannot get from paid labour:

We live in a world where the connection between effort and reward is fragmenting. In our past, we hunted, gathered and built...We could observe, track and consume the fruits of our labour. We could see the connection between our sweat and toil, and the value we derived from them. In today's globally dispersed capitalist machine, this sense is disappearing.

This is pure Marxism. Marx thought that people had a desire for self-actualization through work, but that capitalism thwarted this urge*. In capitalism, he wrote:

Labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself.

Jon Elster claims that Marx "condemned capitalism mainly because it frustrated human development and self-actualization."

Marx was right. The fact that we spend our leisure time doing things that others might call work - gardening, DIY, baking, blogging, playing musical instruments - demonstrates our urge for self-actualization. And yet capitalist work doesn't fulfill this need. As the Smith Institute said (pdf):

Not only do we have widespread problems with productivity and pay, as well as growing insecurity at work, but also a significant minority of employees suffer from poor management, lack of meaningful voice and injustice at work. For too many workers, their talent, skills and potential go unrealised, leaving them less fulfilled and the economy failing to fire on all cylinders.

This poses the question: why isn't there more demand at the political level for fulfilling work?

The question gains force from two facts. First, autonomy at work is a big factor in life-satisfation. Politicians who want to improve well-being - as Cameron once claimed to - should therefore take an interest in working conditions. Secondly, workers who are happy - less alienated - are more productive. Less alienation should therefore help to close the productivity gap between the UK and other rich nations, which in turn should raise real wages.

Despite all this, working conditions are barely on the agenda at all in this election. Politically, the workplace is, as Marx said, a "hidden abode."

One reason for this is that politics has largely ceased to be a vehicle for improving lives. It is instead a form of narcissistic tribalism and low-grade celebrity tittle-tattle: when will Cameron resign? Who'll replace him? What does Miliband's kitchen look like?

And in this way, politics serves the interests of the boss class and not workers. Capitalist power is exercised not just consciously and explicitly, but by determining what becomes a political demand and what doesn't. Here's Steven Lukes:

Is it not the supreme exercise of power to get another or others to have the desires you want them to have - that is, to secure their compliance by controlling their thoughts and desires?...Is it not the supreme and most insidious use of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things?

* His ideas are explained here by Gillian Anderson. I might be gone some time...

March 24, 2015

Banning cash

Ed Conway in the Times endorses Ken Rogoff's suggestion (pdf) that we should abolish cash. This seems to me completely infeasible, in at least three different ways:

- It is a grossly illiberal measure - the banning of capitalist acts between consenting adults, to use Robert Nozick's expression. I can't see voters tolerating this, especially as the move would be a means (pdf) of imposing a tax upon bank deposits: negative interest rates are analogous to a tax.

- Some 700,000 people don't have bank accounts. Many more use cash as a means of controlling how much they spend. For these, a cash ban would be a massive inconvenience.

- It wouldn't work. As John Cochrane says, people could get round the ban (and avoid the inconvenience of negative rates) by various measures such as buying gift cards or prepaying taxes and utility bills.

Despite all the talk of the growth of virtual currencies and digital payments, cash remains popular: notes and coins in circulation have been growing steadily for years, suggesting that the public has a use for them.

Banning cash, therefore, strikes me as one of the most impractical ideas I've heard - and seeing as I was a teenage Trot, that's a big claim.

Now, when intelligent men have silly ideas, ideology is often to blame. And it's not hard to see the ideology in this case. The main argument for banning cash (other than to inconvenience tax-dodgers, which is no stronger an argument now than it has been for years) is to facilitate sharply negative interest rates. But if you want to stimulate the economy - which might be a more pressing requirement come the next downturn rather than now - there's an obvious alternative: looser fiscal policy.

The only reason to suggest something as outlandish as banning cash is that you believe this alternative to be impossible.

Now, I don't believe this for a moment. In our world of negative real interest rates and a shortage of safe assets a bond-financed fiscal expansion is possible. And if it isn't, a money-financed one - a helicopter drop if you like - would be. Surely, either of these are more politically feasible than a ban on cash. To believe otherwise - given the difficulties of the latter - is, I suspect, to have an ideological animus against fiscal policy.

But let's say I'm wrong. Let's suppose that there are circumstances in which we are at the ZLB and in which fiscal policy is ruled out and in which we then face some sort of shock so bad as to require sharply negative interest rates and a ban on cash. (I leave the reader to judge how easy it is to imagine such a world.) Would such a world really vindicate the worldview of those who prefer monetary to fiscal expansion? Or would it instead be better evidence for the Marxian claim that capitalist economies are dangerously unstable?

March 23, 2015

Insincere apologies

Should politicians make false apologies? I ask because of Janan Ganesh's claim that Labour has been "monstrously incompetent" in failing to apologize for its fiscal policy before the crisis:

Had the Labour party owned up to its profligacy in office during the previous decade, it would now have the moral licence to mock [Osborne's] failed deficit target...

Instead, Labour will not even concede that it was wrong to run a structural deficit in the years leading up to the crash, by which time Britain was a decade and a half into an economic expansion. A party that is still borrowing in those circumstances will never see a reason not to borrow.

The economist in me disagrees with this. I sympathize with Simon's retort that allegations of profligacy are "nonsense." I say so for four inter-related reasons.

First, there was no boom before the crisis of 2008. Quite the opposite. The IFS said:

The last decade as a whole was characterised by a very poor performance for average incomes. Between 2002â03 and 2009â10, no single year saw an increase in median income of more than 1.0%.

It estimates that in the five years to 2007-08 median real incomes rose just 0.5% per year. This is the sort of stagnation which might justify counter-cyclical fiscal policy.

Secondly, in the mid-00s the corporate sector was running a large financial surplus: because of what Ben Bernanke called a dearth of investment opportunities, its savings far exceeded capital spending. As Frances says, sectoral balances must sum to zero. A corporate surplus thus requires someone to run a deficit. With foreigners also loath to borrow, that someone was the UK government. To put this another way, had the government tried to tighten fiscal policy against a background of the investment dearth, we'd simply have had even weaker economic activity*.

Third, given the inflation target, tighter fiscal policy means looser monetary policy. That might have led to even worse speculation and malinvestments by banks.

Fourthly, bond yields were falling during the 00s; from 2001 to early 2007, ten year real yields fell from over 2.5% to under 2%. That tells us that financial markets were not worried about "profligacy" but were concerned about weak real growth.

And even George Osborne at the time agreed. In 2007, he promised that a Tory government would match Labour's planned spending increases.

I'm pretty clear, then, that it would be bad economics for Labour to apologize for its fiscal policy**.

But would it be bad politics? Here, I'm not so sure. On the one hand, doing so would play into the silly Tory narrative that they are cleaning up Labour's mess. But on the other hand, a false apology might serve the same function as apologies for other historical misdeeds such as the slave trade. As Theodore Dalrymple said, insincere guilt can be a form of moral self-aggrandizement. And because people tend to take others' self-assessments seriously, this might give Labour a better basis for criticizing Osborne's failure to to cut the deficit by much. Politically, therefore, Janan might be right.

The issue here, though, extends beyond fiscal policy. Labour says it "got things wrong on immigration in the past." If I vote Labour in May, it'll be because I believe that apology to be insincere. In a polity in which the media is biased and the public irrational and ill-informed, there might - just might - be place for lies in politics.

* As I've said, it wasn't the case that fiscal policy in the 00s crowded out capital spending: the investment dearth was exogenous to fiscal policy.

** I don't say this to exonerate Labour. You could argue that looser fiscal policy should have taken the form of tax cuts rather than spending increases. And you can certainly argue that its spending was unproductive.

March 20, 2015

The productivity policy paradox

"Nearly all future growth depends on a productivity resurgence" says Martin Wolf. This being so, Simon is right to deplore the fact that George Osborne never mentioned the productivity stagnation in his Budget.

This, though, raises a paradox - that whilst there seem to be lots of possible policies which might raise productivity, neither of the main parties seems to be taking much interest in them: even Labour seems keener to talk about the symptom of low productivity - low real real wages - than about the causes and solutions to it.

Here's what I mean. Policies to raise productivity (pdf) might reasonably include some mix of the following:

- Infrastructure investment. Workers aren't productive if they are waiting for a train or stuck in traffic.

- Facilitating learning. Nick Bloom and colleagues have estimated (pdf) that over a third of the gap in total factor productivity between the UK and US is due to inferior management. Some of this gap might be closed if only managers were more aware of best practice. In this context, the very fact that the UK's productivity is lower than the G7 average is, in a sense, encouraging. It means we don't need new innovations to boost productivity; we simply need to learn what the French, Germans and Americans are doing. This also requires...

- Better vocational skills. Translating existing ideas into actual productivity requires skilled workers.

- More worker democracy. "shared capitalism seems to boost productivity" say Bryson and Freeman. Sharing profits encourages people to work harder. It also encourages them to find the small marginal gains that can cumulate to raise efficiency.

- A better financial system. A lot of productivity growth (pdf) comes from efficient firms entering markets and inefficient ones leaving. However, with bank lending still falling (pdf) whilst zombie firms are struggling along, this entry-exit process is clogged up and needs fixing. Some might say this requires the encouragement of venture capital and private equity, others a state investment bank.

- Stronger competition policy. The threat of losing market share to rivals should stimulate efficiency improvements.

- Better planning regulations. A hefty chunk of US productivity growth in the 90s came (pdf) from the growth of big box retailing. Do UK planning laws really facilitate such innovations?

- Higher aggregate demand. January's CBI quarterly survey showed that half of UK manufacturers cited uncertainty about demand as a factor limiting capital spending. Higher aggregate demand might also boost productivity by reducing unemployment, thus forcing firms to find ways of getting workers to work better rather than simply hire more staff. Verdoorn's law tells us that strong demand raises productivity. History tells us the same: UK productivity grew much faster during the 1947-73 long boom than at any other time.

- Increased equality. There are reasons to believe that inequality reduces productivity - perhaps by reducing trust (pdf), or by encouraging the rich to invest in protecting (pdf) property rights rather than in innovation.

Whilst this list isn't comprehensive, it's pretty long. There's a reason for this. The precise causes of relatively low productivity will differ from place to place and firm to firm - hence the need for a multi-pronged attack.

And here's my paradox. All of these ideas, except perhaps the last, should lie within the Overton window - though lefties and righties might reasonably disagree about the weights upon them. We have, therefore, a reasonable agenda for raising productivity.

And yet neither main party is putting anything like as much stress upon this as, I guess, most economists would like. This is yet another example of how there has emerged a big gulf between politicians and economists.

A caveat: It's possible that I'm being too optimistic. This paper claims that "there are few, if any, feasible policies available that have a significant effect on long run growth rates". However, it might be possible to raise productivity in the shorter-term (by which I mean several years). And what's wrong with testing their hypothesis? Anyway, I very much doubt that this paper explains politicians' lack of interest in raising productivity.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers