Chris Dillow's Blog, page 106

February 4, 2015

Anti-business

There's a point being missed in the debate about whether Labour is anti-business - that there is, in fact, a good case for being anti-business.

I don't just mean that business dodges taxes and pays low wages. Such talk of unfairness distracts from the fact that, in recent years at least, business has simply failed.

For one thing, the greatest economic disaster of the last 80 years was a failure of business - the collapse of banks in 2007-08.

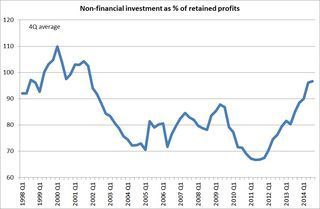

And for another, business has failed to invest in real assets despite making big profits. Since 2000 non-financial businesses' retained profits have exceeded investment in equipment and inventories by a cumulative £478.7bn*. In this sense, business has become an extractive institution, taking more money out of the economy than it has been putting in.

The fact that we're talking about secular stagnation shows that business is failing.

Business - at least in the UK - has become very good at extracting corporate welfare in the form of cushy government contracts, but much less good at riskier innovative ventures. Indeed, one could easily argue that the implicit subsidy to banks per banker is greater than spending on the welfare state per recipient.

In this context, we must distinguish between business and markets. Business is about hierarchy and control; markets are about dispersing power. Markets are about competition, whereas business tries to suppress competition and seek monopoly power; the last thing big business wants is creative destruction. A pro-business government would seek to protect incumbents through red tape that strangles small firms; tough copyright laws; generous outsourcing and procurement policies; and tax breaks. A pro-market government would do the exact opposite, and do everything it could to promote competition. Governments can - and should - be anti-business but pro-market.

All this poses the question: why, then, is Labour scared of being seen as anti-business? The Times gives us the answer. It quotes Tony Blair:

If chief executives say it is Labour that will put the economy at risk, who does the voter believe? Answer: the cief executives. Once you lose them, you lose more than a few votes. You lose your economic credibility.

But why do bosses have such influence? Partly, it's because politicians have so little credibility. But there are also two other reasons.

One is that the media - and the BBC is as guilty as anyone - sets up bosses as being general purpose experts: their opinions on the wider economy are often reported as authoritative in the way that others are not. This, though, misses the point that businessmen are at best experts only at running their own businesses - or in Stefano Pessina's case, inheriting them - and often not even that. As fans of many football teams will tell you, an ability to run one business often doesn't imply an ability to run another.

Also, bosses have managed to mythologize themselves as heroic, risk-taking leaders. But as we saw when Citylink collapsed, this is a fiction: it is workers and small contractors who bear risk, not big businessmen.

"Business leaders" are rather like corrupt medieval clergymen: they use an ideological fiction as a means of extracting wealth and power. What we need is a Martin Luther or Thomas Cromwell.

* I stress retained profits: these are the profits left after taxes, interest payments and dividends.

February 3, 2015

WEHT free market pessimism?

Where are there so few free market pessimists? A post by David Henderson raises this question. Responding to Noah's claim that fossil fuels will run out, he says:

As the price of an energy source rises, entrepreneurs have a strong incentive to invent, develop, and produce alternate sources.

This is a longstanding and common position among supporters of the free market - that the market will help us overcome, or sidestep, energy shortages. And it has been correct for many years. As David says:

Every single time someone has predicted that they we will run out of oil, that person has been wrong. What reason is there to think that prediction today will be right?

However, this logic isn't watertight. The fact that things have happened in the past does not guarantee they'll continue to happen. As Bertrand Russell famously said:

The man who has fed the chicken every day throughout its life at last wrings its neck instead, showing that more refined views as to the uniformity of nature would have been useful to the chicken.

Which brings me to my question. Although David's optimism is about humankind's ability to overcome resource constraints is often associated with free market ideas, there is no necessary reason why this should be. One can, coherently, argue that whilst free markets are necessary to bring forth innovation, they are not sufficient. In fact, it's quite possible that it is now harder to make innovations than it was before, simply because we've already discovered the easy ideas.

Such pessimism is quite compatible with a belief in free markets. One could argue that, if economic growth is harder to achieve, then allocational efficiency becomes more important; if we can't produce more from existing resources, we should at least ensure those resources are put to best possible use. And a lack of growth makes it more important to incentivize entrepreneurs to exploit the few ideas there are.

It's entirely logical to believe both in free markets and in the view that diminishing returns will eventually overcome technical progress. This is especially true given that the pace and direction of technical change is largely unpredictable. In fact, it was pretty much what David Ricardo believed. And if it was good enough for him, it'd good enough for us.

Hence my question. Given that free market pessimism seems such a tenable view, why, AFAIK, is it so rare? Why does optimism about human potential seem to be more correlated with a belief in free markets than I'd expect?

I was going to suggest that free marketeers tend to have a more optimistic disposition than their critics; a lot of egalitarianism is founded upon Rawls's maximin principle, which is an ultra-pessimistic decision rule. But this seems inconsistent with research which shows that political conservatives (pdf) tend to be more risk-averse than lefties.

You could retrieve my hypothesis by arguing that a belief in free markets isn't politically conservative - but I fear you might struggle; the two are closely associated in the US at least.

Which leaves me with a genuine question: why has free market pessimism almost disappeared, despite being so reasonable? My more partisan readers might say it's because the free market right has become anti-scientific. Even if there's some truth in this, I'm not sure it's a complete explanation. For me, then, there's a puzzle here - and, given the virtue of cognitive diversity, something to be regretted.

February 2, 2015

Is democratic Keynesianism possible?

Simon calls for fiscal policy to be set independently of government, to prevent it "being corrupted by politics and ideology." This might seem like pointy-headed technocracy. In fact, it is more radical than that.

To see why, consider why we cannot rely upon government to pursue an intelligent fiscal policy at the zero bound.

One reason is that the media promotes economic illiteracy through mediamacro and bubblethink.

Another reason was, of course, pointed out by Michal Kalecki back in 1943. "The assumption that a government will maintain full employment in a capitalist economy if it only knows how to do it is fallacious" he said. Business does not want fiscal policy to create full employment because this would deprive it of political power:

Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence. If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment..This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy...But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of 'sound finance' is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence.

There can be little doubt that business has captured government.We saw an example of this yesterday. Stefano Pessina's claim that a Labour victory would be "catastrophic" was reported as if it were news that a billionaire isn't keen on leftish governments; I doubt that a benefit claimant's view that a Tory victory would be "catastrophic" would get so much attention.This is just on example of how the rich have disproportionate political influence.

In this sense, I read Simon as making a very radical claim - one which is more Marxian than Keynesian. "Democratic" policy-making cannot serve the public interest, because it is subverted by capitalists' interests. This represents a challenge to naive social democracy, which thinks that governments can do the right thing if only they have the will and courage.

January 31, 2015

Micro efficient, macro inefficient

In the day job, I endorse Paul Samuelson's dictum that stock markets are "micro efficient" but "macro inefficient". This isn't to say that they are wholly efficient at the micro level: there are some anomalies and I prefer to think of markets as adaptive. But for practical purposes, investors should act as if the market were micro efficient and hold tracker funds.

Theories don't have to be wholly true to be useful, and only the most Casaubonish pedant thinks otherwise.

But here's the thing. The idea of markets as "micro efficient" but "macro inefficient" might be one of the few ideas in the social sciences that generalizes. Keynes, for example, certainly thought this was true of labour markets:

I see no reason to suppose that the existing system seriously misemploys the factors of production which are in use...When 9,000,000 men are employed out of 10,000,000 willing and able to work, there is no evidence that the labour of these 9,000,000 men is misdirected. The complaint against the present system is not that these 9,000,000 men ought to be employed on different tasks, but that tasks should be available for the remaining 1,000,000 men. It is in determining the volume, not the direction, of actual employment that the existing system has broken down.

One might add that Marxists' main complaint against capitalism is that it is macro inefficient rather than micro inefficient. Their beef isn't so much that capitalism produces too much of one one good and not enough of another, but rather that it had a tendency towards crises; that it is exploitative and alienating; and that it has unpleasant cultural effects, for example by leading us to regard others with greed or fear which, Cohen says (pdf), "are horrible ways of seeing other people." These are all macro problems, not micro ones.

Again, this is not to claim that capitalism is wholly micro efficient; leftists believe that markets over-supply finance, weapons and pollution and under-supply more caring occupations - though whether these are state failures or market failures is moot.

All this poses a question. What sort of economic system does the idea of micro efficiency but macro inefficiency lead to?

We can discount the social democratic option. We know now - as Keynes did not - that macroeconomic policy within market capitalism is not sufficient to create full employment, perhaps for reasons identified by Kalecki or perhaps because capitalists capture the state; still less does it solve the faults alleged by Marxists. Nor am I attracted to the participatory planning of the sort advocated by Robin Hahnel; it seems like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. This leaves some form (pdf) of market socialism and economic democracy.

January 30, 2015

Inequality, non-linearities & growth

Might there be a non-linear relationship between inequality and growth? A new paper suggests so. It finds that "there is a range of values of changes in inequality where the link [with GDP growth] is weak", but that big reductions in inequality do boost growth. It concludes:

Not all polices that reduce inequality will lead to faster economic growth. Instead, only those that greatly reduce inequality will.

The paper is purely statistical, which poses the question: what sort of mechanisms might generate such a pattern?

One possibility is that inequality depresses growth by generating a culture hostile to prosperity. For example, it might lead to mutual distrust (pdf) which is bad for growth, or to learned helplessness among the poor which saps their energy - say, to stay on in education or to take more initiative at work. It requires a big change in inequality to remove these cultural obstacles to growth. A change in the Gini coefficient of one or two percentage points doesn't much change culture.

A second possibility is that inequality is bad for growth because it imposes credit constraints upon workers which prevents them from forming worker coops even though it might be efficient to do so. A small reduction in inequality might not be sufficient to overcome these constraints.

Thirdly, whilst modest redistribution might have some benefits - for example in shifting incomes from those with a low propensity to consume to those with a higher - it can also have an adverse effect. If it leads to expectations of further redistribution, it could depress investment as capitalists anticipate low post-tax returns. However, a big redistribution might not have such ill-effects if it reduces the risk of future further tax rises by, in effect, buying off discontent. This is what James Buchanan had in mind when he wrote:

The rich man, who may sense the vulnerability of his nominal claims in the existing state of affairs and who may, at the same time, desire that the range of collective or state action be restricted, can potentially agree on a once-and-for-all or quasi-permanent transfer of wealth to the poor man, a transfer made in exchange for the latter's agreement to a genuinely new constitution that will overtly limit governmentally directed fiscal transfers. (The Limits of Liberty, 7.10.40)

He wrote that in the mid-70s - a time when the threat of redistribution might well have been depressing investment and growth.

Now, I'm not saying all this to say that radical redistribution is definitely a good thing; that requires a lot more arguing. I do so instead to challenge a common prior among social democrats - which might well arise from a presumption that the economy is a simple linear system - that mild reformism and "moderation" is sensible and "realistic" whereas radicalism is economically unsound. It ain't necessarily so.

January 29, 2015

The left's ideas

In the Times, David Aaronovitch accuses the left of being "completely without ideas" and of sinking into the politics of "symbology" because they have "nothing else." I'm in two minds about this.

One the one hand, it seems wrong. A few decent ideas get us a longish way towards leftist ideals: an expansionary fiscal policy including massive housebuilding to get us away from the zero bound; a citizens' basic income; a serious jobs guarantee (pdf); and worker democracy. One might add to this higher taxes on inheritance and top incomes and (though I'm more sceptical of these) wage-led growth and participatory economics. The left has lots of decent ideas which are reasonably well grounded in evidence and logic: see, for example, the real utopias project.

This, though, merely poses the question: how, then, can someone as intelligent as David think otherwise?

The answer is that such ideas, for the most part, are outside the Overton window; they're not discussed in mainstream media-political circles - or if, they are, it is appallingly badly done.

There are several reasons for this.

One is that the media filters out such ideas. "Mediamacro" has constructed a hyperreal economy in which the deficit is the economic problem. And deference towards bosses prevents journalists from even posing the question: mightn't worker control sometimes be more efficient?

Our warped media, though, in part reflects public opinion. Numerous cognitive biases serve to support hierarchy and inequality and so close off thinking about alternatives. (In saying this, I'm not making a specifically Marxian point. It was Adam Smith who complained of our "disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition" (Theory of Moral Sentiments I.III.28).)

Another problem is that there's adverse selection in politics. Whatever other abilities Natalie Bennett might have, they do not include an ability to argue for even well-founded policies. And this highlights a wider problem. Politics selects against intellectuals: as Nick Robinson said of Jonathan Portes, "he would not have a chance of getting elected in a single constituency in the country." Instead, what's valued is a perceived ability to "connect" with the voters. And this means following public opinion, not changing it.

But there is, though, also a problem with the left itself. Since the 80s much of it has lost interest in economics - except, it seems sometimes, to dismiss the entire discipline as neoliberal ideology. As Nick says:

I have seen half my generation of leftists waste their lives and everyone else’s time in petty and priggish disputes about language. They do it because it’s easy, and struggles for real change are hard.

What I'm saying here is that, if David is looking for leftist ideas in the media-political bubble, he's looking in the wrong place. As a great man said, the revolution will not be televised.

January 28, 2015

Marginal product, & incomes

How do you convert ability into income? This is a question promoted by Ann Bauer's claim that novelists often need subsidies from their family. Her point broadens. Many artists struggle to get by: I suspect Jolie Holland speaks for many when she says she barely makes a living.

A novelist, academic and CEO might have very similar intellect and skill levels, but their income could differ by factors of thousands - and, as Will points out, academics' working conditions are deteriorating. Why the difference?

The conventional neoclassical answer is that wages equal marginal product, and that CEOs have a higher marginal product than others. This is a just-so story which glosses over a lot.

For one thing, what matters is that one's product be monetizable and appropriable. The great writer or musician creates an enormous amount of consumer surplus, but she cannot capture this for herself. Quite the opposite; as Gillian Welch sang*, she is under pressure to give away her work. Similarly, if you believe human capital theory, academics - at least the better ones - create billions of pounds of value. But they don't see much of it. By contrast, the CEO's output is more monetizable.

There are at least five reasons for this.

1. Ideology. Hiring committees' wishful thinking and overconfidence lead them to believe that they can hire a great CEO who can add millions of pounds of value to a business - so they pay a premium for what might turn out to be mediocre performance or worse. Demand, remember, can be an ideological construct.

2. Supply constraints. Thousands of people think they can write or sing. Their entry into the market makes it harder for the more able artists to get themselves heard. By contrast, a manager can only show his ability by having worked with expensive assets. This creates a lack of supply of managerial talent. The upshot, as Marko Tervio has shown, is high wages for modest abilities.

3. Rent-sharing. Joanne Lindley and Steven McIntosh show that workers in the finance industry earn more than others, even controlling for skill. This, they say, is because of rent-sharing. Bankers go home with big money for the same reason zookeepers go home with shit on their boots: if there's a lot of stuff around, some of it will stick to you. This also explains why footballers earn more than they did in the 60s; it's not because they have more ability, but because there's more money in the game. There are fewer rents in academia - hence lower pay.

4. Efficiency wages. Banks' traders and CEOs generally must be bribed in order to not sell off the firms' assets cheaply. Nobody feels the need to bribe academics to stop them teaching badly.

5. Reciprocity. The mere act of communicating with people leads them to treat us more generously. And conversely, if people are out of sight we are apt to treat them meanly. This gives CEOs an advantage.They are often on personal terms with members of the remuneration committee (if only because they often attend its meetings). By contrast, most of the rest of us have our pay set by people less close to us.

My point here is that Ed Walker is right. Marginal product theory is inadequate at explaining inequality. If you want to understand it, you must look beyond the claim that wages equal marginal productivity. We must ask: what is marginal product measuring, and what isn't it? And: through what mechanisms do wages equal (or not) marginal product?

* Everything worth knowing can be learned from country music and football.

January 27, 2015

Basic income: some issues

I try not to watch politics programmes on TV. Andrew Neil's interview with Natalie Bennett about a basic income reminds me why.

I'm appalled by Natalie's inability to answer his first question: how to pay for it? The Citizens Income Trust has set out one way (pdf)* to do so: quite simply, abolishing the personal allowance and welfare benefits raises hundreds of billions.

Mr Neil's implication that a BI of £71pw is inferior to a personal allowance of £10,000 for the low paid is also wrong.

Take for example, someone earning £14,000 a year. She currently pays £800 in tax, giving a net income of £13,200. Under a basic income, she'd have to pay tax on all this £14,000. That's £2800. But she gets £3692 in BI. That gives a net income of £14,892. She's better off. BI, then, is better for the low-paid than the current £10,000 tax allowance.

This is even more true when we remember that low-paid work is often insecure. A BI is better for those who shift from work to unemployment and back again, as it ensures a continuous income with no threat of benefit delays.

In these senses, the interview was a car crash on both sides: Neil posing questions that are easily answered, and Bennett failing to answer even these.

This poses the question: what, then, are the more intelligent objections to BI?

The problem isn't that a BI gives too little to children, the disabled or pensioners. The CIT's costings show that they can get top-ups. Nor is it that a BI ignores housing costs. The CIT's costings show that housing benefit can be retained - though I personally think it should be phased out over time, as a big housbebuilding programme should reduce rents and hence landlord benefits.

Nor is it clear that a BI's treatment of immigrants is wrong. Because it's a citizens' basic income, immigrants would not be entitled to it - though they alternative insurance arrangements for them are possible and desirable. Such a restriction, though, should reduce public antipathy to immigration by removing the fears that they are "taking our benefits."

So, what are the more grievous problems?

One of the more common ones is that an unconditional income violates the norm of reciprocity and so would be unpopular. Dawn Foster says:

If you genuinely create a "something for nothing" culture – rather than one that exists merely in the fevered imaginations of tabloid readers – the backlash could be harsh.

To some extent,though, this is a feature, not a bug. Given that jobs are scarce it is just pointless and cruel to harrass the jobless into non-existent work. Indeed, helping some to drop out of exploitative jobs would force employers to improve their job offers, to the benefit of those who want to work.

However, it's doubtful how big a problem this is. Phil points out that it isn't a significant issue with Alaska's BI. And econometric simulations suggest it might not be for the UK either. In fact, insofar as a BI makes it easier to move into work - because there's no danger of losing income or of being better off on the dole - it might even reduce (pdf) unemployment.

For me, though, there are two other issues.

One is that a BI does create some losers. Anyone earning over £18,460 is worse off with a BI of £71pw than under a £10,000 personal allowance. This is a big problem. It suggests that a BI can only be popular if accompanied by more redistribution - higher taxes on the rich to pay for a lower tax rate on lower earnings and/or a higher BI.

Secondly, there's the question: is there the state capacity to effect such change? Everyone knows the shift to Universal Credit has been a mess. I'd like to think this because of Iain Duncan Smith's personal inadequacies. But it might also be that the state apparatus lacks the ability for reform. One of BI's great virtues - its simplicity and low administrative cost - also creates a big constituency in Whitehall opposed to it.

I suspect - hope - that there are solutions to this. A BI should not be introduced by the fiat of a single government. Instead, we need a new Beveridge report which would publicize its merits and ensure that it benefited as many people as possible. Only when it has such mass support should it be implemented.

* This is just one possible costing. Here's a list of tax reliefs (pdf). You can make up your own savings from these. And here's a collection of papers on basic income.

January 25, 2015

Frederic Bastiat & football punditry

In the day job I call Arsene Wenger a great economist. I'm making a serious point.

An economist is not someone who sits in an armchair pontificating about what's wrong with economics or - worse still - about the future. He is someone who tries to solve or ameliorate particular problems. As Simon says, economists are like doctors: much of my day job consists of giving advice on financial health.

From this perspective, football managers are economists. The task of picking a team is a constrained optimisation problem. And the job of a coach is largely to find the best solution to trade-offs. For example, do you press the opposition and risk being caught out of position, or do you sit back, keep your shape but concede possession? Do you play it long and have a high chance of giving the ball away in safe areas, or play it short and run the smaller but more costly risk of giving it away in your own third? Do you get men behind the ball and not concede goals but then lack options when you attack? And so on.

But here's the thing. When we judge whether coaches are making these trade-offs correctly, we often fall into error because of the interaction of two biases.

One is the outcome bias - our tendency to judge decisions by results rather than by circumstances at the time the decision was made: as Dostoyevsky wrote, "everything seems stupid when it fails". The other is a version of the error Frederic Bastiat warned us against - a tendency to look at the seen rather than the unseen.

Take, for example, something Arsenal are often criticized for - pushing fullbacks up too far and so being vulnerable to counter-attacks. It's easy to produce examples of this being costly - though I'll not bother. That's the seen. The unseen is what would happen if the full-backs stayed back. Somewhere in a parallel universe, Arsenal's fullbacks played deeper last Sunday, Nacho Monreal didn't win that penalty and Robbie Savage is criticising Arsenal for lacking an attacking edge. (One implication of the multiverse hypothesis is that there are an infinite number of Robbie Savages - and they call economics the dismal science.)

I say all this for two reasons.

One is that this point generalizes. In a complex world, even the best solutions to trade-off problems will entail some costs. Those solutions should not be criticized for this. For example, holding tracker funds will incur the costs of sometimes missing out on some profitable investments - for example when mega-caps underperform and so most stocks beat the market or when momentum stocks do well. But these costs must be weighed against costs avoided, such as high dealing charges. Decisions should be judged by their totality of costs and benefits, not by single costs. The same, of course, applies to macroeconomic policy-making: the cost of higher inflation must be weighed against the cost of higher unemployment. And it applies to politics generally.

Secondly, there is a close affinity between economics and sport; each can illuminate the other. I suspect you could learn more about economics from football than you could from the empty suits at Davos this week.

January 23, 2015

Real wages & inflation

One thing that has peeved me recently is the claim that falling inflation is good for real wages. This is partially true, and partially false.

It's true in the sense that lower oil prices raise the real incomes of oil consumers. It's also true that a surprise drop in inflation of the sort we've seen can temporarily raise real wages.

However, in the longer-run, real wages aren't affected by inflation. If they were, we could achieve higher wages by (credibly) reducing the inflation target - but nobody believes this.

Instead, real wages depend upon real things like productivity growth and workers' bargaining power, and these aren't much affected by inflation: at moderate levels of inflation, there's no link between inflation and GDP growth, for example.

This poses a danger - that, in the absence of real supports for real wages, the temporary benefit of lower inflation will be clawed back, in the form of lower future nominal pay rises.

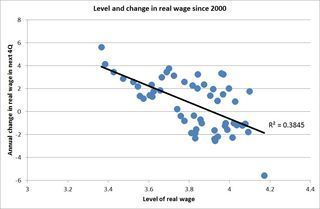

My chart shows the point. It plots the level of real wages (the average wage index divided by the CPI) against the change in real wages in the next four quarters. The relationship is clearly negative. This implies that a surprise rise in real wages because of, say, a surprise drop in inflation leads to lower future pay growth.

This could happen again. It's not just me that thinks so. Here are the minutes of the last MPC meeting:

It was possible that the fall in near-term inflation might become more persistent if it lowered inflation expectations, pay and other cost growth in a way that became self-perpetuating. Inflation had fallen globally and was expected to reach its trough in the United Kingdom in the early part of the year when a large proportion of pay claims were settled. It was therefore possible that the pace of nominal wage growth would be weaker than otherwise.

This is an especial danger because two big determinants of pay growth aren't terribly helpful.

For one thing, productivity is still awful. This week's numbers show that hourse worked rose by 0.5% in September-November. With the NIESR estimating that GDP grew 0.7% then, this gives us productivity growth of just 0.2%.

Secondly, it's not obvious how much bargaining power workers have. Yes, unemployment has fallen which strengthens their hand. But on top of the 1.9m formally out of work there are also 2.3m people outside the labour force who want a job and over 1.3m part-timers who want full-time work. This represents an excess supply of labour equivalent to 13.7% of the working-age population. This might continue to hold down pay growth.

To check this, I ran a quick and crude regression of reage wage growth since 2000 upon lagged unemployment (the official rate), the lagged level of real wages, and productivity growth. Such as equation has an r-squared of 69% since 2000. It tells us that, if productivity rises 1% in the next 12 months then real wages will rise 1.3% (standard error = 1.3pp). This is better than we've seen recently. But it's well below the 2.3% annual growth we saw in the seven years before the recession.

I don't offer this as a definitive forecast. Instead, I offer it as evidence that what matters for real wage growth is not inflation but more fundamental forces. And these aren't yet obviously very favourable.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers