Chris Dillow's Blog, page 108

January 9, 2015

Freedom's supporters

"Why do liberals find it so hard to persuade Muslims about free speech?" asks Sunny. And he gives a good answer - that so many of those who are proclaiming their support for freedom are inconsistent or, as David North puts it, dishonest and hypocritical.

As Jacob Levy points out, it is hypocritical for the French establishment to support free expression for those wanting to mock Islam whilst at the same time forbidding Muslims from expressing their religion by wearing the veil.

Not that we need look overseas for hypocrisy. Nick Clegg has been (rightly) praised for saying:

You cannot have freedom unless people are free to offend each other. We have no right not to be offended.

But this point shouldn't be directed only to Muslims. He should have a word with Police Scotland, which tweeted just a few days ago:

We will continue to monitor comments on social media & any offensive comments will be investigated.

That's in a country where "offensive" football chants are criminalized, where people are punished for "offensive" expressions, and where there are calls pretty much every day for someone who has "offended" others to be sacked or punished by the law.

Not that the hypocrisy is confined to those in power. As Nick Cohen has said, it's ubiquitous:

The same people who scream “censorship” and “persecution” when one of their own is targeted lead the slobbering pack when the chance comes to censor and persecute their enemies. They want them fined, punished and sacked.

In fact, I suspect we should regard the Charlie Hebdo murderers not just as extreme Muslims but rather as extreme versions of the narcissists who want any "offence" against their purified identities to be punished.

Herein, though, lies my question. Where are the real, honest, defenders of freedom?

We'll obviously not find them in the police or security services who forever want to expand their powers. Nor are the main political parties unequivocally on the side of freedom. The coalition, like New Labour, has actually increased the number of new criminal offences. And the next election is likely to be a competition for who can most restrict freedom of movement. Nor should we expect companies to support freedom. Those bloggers who have criticized newspapers for not reprinting Charlie Hebdo's cartoons miss the point - that people become bosses by surrendering principle to pragmatism, which is no basis for a vigorous defence of freedom. More generally, as Nick says, companies use libel laws to suppress critics.

It's in this context that we should remember one of Marx's insights. Ideals, he thought, triumph not because of their intellectual strength but because of their political power: capitalism, he thought, would be overthrown not by sweet reason but by the power of the working class. The problem that we supporters of freedom have is that whilst we have right on our side, we don't have might.

January 8, 2015

Deflation: why worry?

Should we worry that the euro zone is in deflation (pdf)? Certainly, deflation is a symptom of a severe problem - that of weak demand which has resulted in almost one-in-four (pdf) young people being out of work. And the very fact that deflation is unfamiliar might create uncertainty which itself is bad for economic activity. Beyond this, however, I suspect that what we have to fear is not so much deflation as bad policy.

For one thing - as Robert Peston points out - the fall in the CPI is entirely due to lower oil prices, which should raise real incomes and activity. (Note, though that even excluding energy inflation is only 0.6 per cent, which is well below the ECB's target of "below, but close to, 2%." In this sense, there has been a failure of economic policy.)

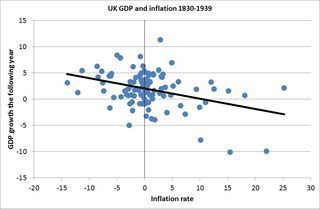

And for another thing, history tells us that deflation needn't lead to weaker growth. My chart plots GDP growth against inflation in the previous year for the UK before WWII - a period when deflation was common. You can see that, if anything, deflation led to faster growth than did inflation. Of course, there are many differences between 19th Century England and the euro zone today (though maybe not so many in Germany), but this historical evidence suffices to tell us that there is no necessary, inherent reason why deflation must lead to worse economic performance.

All this said, there is a danger here. It lies in the dynamics of government debt. Remember the simple equation which tells us what primary budget balance governments must run to stabilize the debt-GDP ratio. It is:

d * [(r-g)/(1+g)]

where d is the debt-GDP ratio, r the nominal interest rate and g the nominal growth rate.

This equation tells us that if g falls relative to r, then more fiscal austerity is needed to stablize the debt ratio. And such a fall is quite possible if (for example) permanently lower inflation is accompanied by markets worrying about debt sustainability, which would keep bond yields high.

This poses the danger of a vicious circle in which deflation leads to austerity which leads to further deficient demand and deflation.

What could prevent this? In theory, the mere existence of the inflation target should do so; this should keep inflation steady at just under 2%. What's in doubt, though, is whether the ECB can or will achieve this. In this sense, calls for a higher inflation target, whilst perhaps reasonable in other contexts, aren't (yet) relevant; the ECB's not hitting its current target, let alone a higher one.

Instead, there are two other possibilities. One, of course, is full-blown QE. Sure, it's doubtful how much this will raise activity and inflation. But even so, it has another virtue. It would hold down bond yields and so help prevent the rise in r - g that would worsen debt dynamics. In this sense, QE is a form of fiscal policy.

Ah, yes - fiscal policy. The solution to deflation at the zero bound is simply a looser fiscal policy. And, taking the euro zone as a whole, there is plenty of room for this; the OECD estimates that the region is running a surplus on its underlying primary balance.

It is, however, unlikely that this option will be exercised. Which is why I say that the biggest danger for the region isn't so much deflation as bad policy.

January 7, 2015

Endogenous preferences

The conventional neoclassical view that consumers have rational preferences that maximize their utility is wrong, according to new experimental evidence.

Researchers got some students in Prague to taste an unpleasant mixture of Fanta, salt and vinegar and then to say how much they would need to be paid to drink a larger quantity of the concoction, with those who stated a below-median price being required to actually drink it. This exercise was repeated ten times.

They found that subjects' offers were strongly influenced by the median price elicited in previous auctions. This is not necessarily irrational; someone wanting the money rather than the nasty taste would want to bid a penny less than the median. What is odd, though, is that those subjects who were told about the lowest offers offered lower prices themselves, which was against their own interests. "Preferences are endogenously determined by the market process themselves", they conclude.

This is more evidence that peer pressure matters; it influences our decisions to spend or save and our decisions on how to invest.

This experiment shows that these peer pressures matter even when people's choices are anonymous - that is, in the absence of social pressures to conform. They also matter even in purely private contexts, when people must weigh their idiosyncratic distaste for the drink against their desire for money.

Consumers' choices are shaped by the When Harry met Sally principle: "I'll have what she's having."

One reason for this might be that preferences are, within some range, indeterminant; this might also explain another anomaly from the perspective of conventional theory, that consumer choices are shaped by how they are framed. This point was classically made in a famous (though apocryphal) exchange between George Bernard Shaw and a socialite:

'Would you sleep with me for... for a million pounds?' `Well,' she said, `maybe for a million I would, yes.' `Would you do it for ten shillings?' said Bernard Shaw. `Certainly not!' said the woman `What do you take me for? A prostitute?' `We've established that already,' said Bernard Shaw. `We're just trying to fix your price now!' "

In fact, though, Shaw was being a little harsh: his interlocutor's preferences were merely less well-defined than standard theory assumes.

This might explain a lot. It might contribute to the emergence of Adler superstars (pdf) - musicians and authors who make millions despite a lack of talent: as Andrew Hill says, people want to buy what others are buying. It might also explain the Steve Brookstein effect - the tendency for apparently popular X Factor winners to sink quickly into obscurity; it's because popular preferences might not be as strong as they seem.

You might think this is just yet another attack on orthodox neoclassical economics. I suspect, though, that the problem goes further. Political preferences might also be endogenous; other laboratory experiments show that our attitudes to inequality - to take just one example - are shaped by an anchoring effect or by simple resignation. It might, therefore, be that our political preferences are also endogenous and do not serve our interests. If so, the problem with democracy isn't (just) the politicians, but the voters.

January 6, 2015

Hyperbole in politics

The start of the election campaign has already produced silly hyperbole, with the The Tories claiming that Labour's spending plans would be "disastrous" and lead to "chaos" and "real poverty."

The problem with this isn't just the obvious one, that we actually need more public spending and a looser fiscal policy than the Tories are offering. Even if we make the heroic assumption that Tory policy is right, the attacks on Labour are still horrible overstatements.

For them to be true requires some combination of two things to be the case: that slightly larger planned borrowing (the IFS thinks Labour's plans are for a bigger deficit of only around 1.5 per cent of GDP) will lead to big rises in interest rates; and/or that aggregate demand is highly interest-sensitive, so a rise in borrowing costs will choke off economic activity.

Neither of these is the case. Real long-term interest rates have trended downwards since the mid-90s, whilst government borrowing has increased. And if lower interest rates had a very powerful effect on spending, the economy would be booming now as never before.

Even if you believe that a looser fiscal policy would be wrong, it would surely not be a disaster. Not all policies that are sub-optimal are catastrophic. To pretend that they are is just stupid overstatement.

In one sense, such hyperbole is forgivable. One thing that all governments have in their favour is the fear of the unknown. It's natural for incumbents to play upon this by exaggerating the cost of the opposition's policies. And, of course, politicians are selected to over-estimate the good and evil that policies do: you don't go into politics unless you think policies make a big difference.

Nevertheless, such claims are misleading. It is, in truth, very difficult for governments in developed economies to make a decisive difference to economies or societies for good or ill. One reason why politicians are seen as useless is precisely because they cannot make as much difference to our lives as they pretend*.

A big reason for this is that economies are complex. On the downside, this means it is difficult for policies to have big, predictable positive transformative effects. On the upside, though, complex systems can be resilient to suboptimal policies and choices. As Adam Smith said, "there is a great deal of ruin in a nation." One of the under-rated differences between developed and under-developed nations is that the former are more resilient to shocks than the latter.

You might think I'm labouring the obvious here. Maybe. But maybe not. It's not just politicians who are selected to be biased to over-estimate the effects of policy. So too are political reporters. When they report hyperbole without giving it scrutiny they are promoting a false image of the economy - that it is a delicate flower vulnerable to small changes in policy. This is yet another way in which the media constructs a hyperreal economy which is unrelated to what the rest of us live in.

* I don't think the claim that austerity has depressed economic activity is a counter-example here. Fiscal multipliers, in bad times, are a little more than one. If they were 5, 10 or 20, austerity would be disastrous. As it is, it is just bad.

January 4, 2015

Who bears risk?

There's one aspect of the collapse of City Link that deserves more attention than it gets - that it undermines the conventional idea that firms' owners are risk-takers.

Better Capital's stake in the firm took the firm of a secured loan, which means they'll get first dibs on its residual value. Thanks to this, Jon Moulton, Better Capital's manager claims to stand to lose only £2m - which is a tiny fraction of his £170m wealth.

By contrast, many of City Link's drivers had to supply capital to the firm in the form of paying for uniforms and van livery, and are unsecured creditors who might not get back what they are owed. Many thus face a bigger loss as a share of their wealth than Mr Moulton. In this sense, it is workers rather than capitalists who are risk-takers.

This point is not, of course, specific to City Link. Most decent-sized businesses represent only a small fraction of a diversified portfolio for their capitalist owners, whereas suppliers of human capital usually have to put all their eggs into the basket of one firm; only a small minority of us have "portfolio careers" . All that stuff they teach you about the benefits of diversification applies in the real world to capital, not labour.

There are two implications of all this.

First, it means that the idea that capitalists are brave entrepreneurs who deserve big rewards for taking risk is just rubbish. As Olivier Fournout has shown, the idea of managers as heroes is an ideological construct which serves to legitimate power and rent-seeking.

Secondly, it suggests that ownership might in some cases lie in the wrong hands. Common sense tells us that those who have most skin in the game should have the biggest say simply because they have the biggest incentive to ensure that the firm succeeds. As Oliver Hart - who's hardly a raving lefty - says: "a party with an important investment or important human capital should have ownership rights." This is yet another case for worker ownership.

This in turn reminds us of a cost of inequality; sometimes, ownership is in the wrong hands simply because the most efficient owners can't afford to buy the firm.

All this poses the question: are there policy measures, other than worker ownership, which could ensure a more equitable bearing of risk?

One answer would be policies to achieve serious full employment. Full employment would allow workers to reject job offers which expose them to excessive risk, and it would mitigate human capital risk by ensuring that those who lose their jobs - and the collapse of firms is an inevitable part of capitalism - can quickly find new work.

Secondly, we need a more redistributive welfare state. The welfare state is not a scheme whereby "we" pay for "scroungers". It is instead an insurance mechanism. It is a means of pooling human capital risk; we pay premiums (tax) in good times and receive compensation in bad times when such risks (illness or redundancy) materializes. The fact that many workers suffer a massive drop in income when they lose their jobs suggests the welfare state isn't providing enough insurance.

Of course, all these ways of improving risk-bearing fall outside the Overton window.

January 2, 2015

Blair the ideologue

In his interview with the Economist, Tony Blair seems like a sad old man living in the past. He says that "the Labour Party succeeds best when it is in the centre ground" - something which entails "not alienating large parts of business, for one thing”.

What this misses is that things have changed since the 1990s. What worked for Labour then might well not work now.

What I mean is that in the 1990s Labour could plausibly offer positive-sum redistribution and could therefore please both left and right. Take for example expanding higher education. This was leftist - because a higher supply of graduates would bid down the graduate premium and hence help reduce inequality. But it was also rightist because it improved skills and opportunity. Or take tax credits and minimum wages. These were leftist because they reduced poverty, but also rightist because they encouraged work. Similarly, the promise of policy stability was intended both to please business and to encourage job creation.

Such policies were centrist, vote-winning and (within limits) reasonable economics.

However, we don't live in the 90s any more. There are at least five big differences between then and now.

1. In the 90s, New Labour's centrist policies were consistent with mainstream economics. There was a decent overlap between good politics and good economics. This is no longer the case. The political centre supports austerity and tough immigration controls. These are not just inhumane but economically illiterate. The political centre and the economic centre are two very different things.

2. If positive-sum redistribution is at all feasible (and it is an if) it consists in wage-led growth. This is not especially politically centrist.

3. The danger for Labour is no longer merely that voters will leave it for the Tories for fear that it cannot be trusted on the economy. It's also that they won't vote at all or will switch to Ukip because they fear Labour is insufficiently anti-establishment and too centrist; Ukip supporters, remember, overwhelemingly support (pdf) price and rent controls and nationalization. They want a government that alienates business.

4. New Labour thought that managerialism would increase efficiency in the public and private sectors. However, with productivity stagnating in both public and private sectors, the evidence now tells us that this is not the case and that, instead, managerialism is an ideological cover for the enrichment of a minority. Policies to increase equality and efficiency must, therefore, challenge managerialism.

5. In an era of secular stagnation, macroeconomic stability - even if it can be achieved which the experience of 2008 suggests is not possible - is not sufficient to boost investment, innovation and growth. Perhaps, therefore, greater intervention is necessary.

My point here is that Blairism should not be rejected (merely) because it is insufficiently left-wing as Neal Lawson claims, nor (just) because the centre ground is a "nonsensical chimera" as Phil claims. Instead, it should be rejected on the purely pragmatic grounds that the economy has changed since the 90s and so we require different policies. In failing to say this, Blair appears to be an irrelevant out-of-date ideologue.

December 31, 2014

In praise of complexity economics

The Economist's ranking of the most influential economists of 2014 has been derided, and Tyler Cowen provides a more sensible list. But I wonder: which economists should be more influential than they are?

The glib answer here is: whoever corroborates my prejudices. A less glib answer would be the countless economists who are doing good work which is insufficiently appreciated by the public: I try to publicise some of this in both here and in my day job.

But there's another answer I'd like to offer: those economists who have been working in the field of complexity economics. Perhaps the pioneer here is Brian Arthur, who has written a great short introduction (pdf) to the subject. But I'd also mention Eric Beinhocker*, Cars Hommes, Alan Kirman and, in financial economics, Andrew Lo, whose theory of adaptive markets I find an attractive alternative to the efficient/inefficient markets hypothesis.

One feature of complexity economics is that recessions can be caused not merely by shocks but rather by interactions between companies. Tens of thousands of firms fail every year. Mostly, these failures don't have macroeconomic significance. But sometimes - as with the Fukushima nuclear power plant or Lehman Brothers - they do. Why the difference? A big part of the answer lies in networks. If a firm is a hub in a tight network, its collapse will cause a fall in output elsewhere. If, however, the network is loose, this will not happen; the loss of the firm is not so critical. Daron Acemoglu has formalized this in an important paper, and there are some good surveys of network economics in the latest JEP.

The question is: why is complexity economics not more influential?

One reason is that it requires different techniques. It can't be studied merely by problem sets (ugh) devoted to standard optimization techniques. Instead, it requires agent-based simulations (here are a couple of examples), laboratory experiments of the sort done by Charles Noussair among others, or close attention to history and the institutional and cultural settings in which markets operate.

And therein lies a second reason why complexity economics is under-rated. For me, one of its big messages is that context matters. Emergent processes sometimes lead to benign outcomes and sometimes instead to inequality and inefficiency, and which turns out to be the case can hinge on quite small differences. The great economists of the 20th century - such as Keynes, Samuelson or Friedman - tried to offer a general theory. Complexity economics doesn't.

There's a third reason why complexity economics is under-rated. It does not give us a means of foreseeing the future. Of course, conventional economics doesn't do so either. But the difference is that complexity theory tells us that such forecasts might well be impossible - which is not what the customer wants to hear. The best it can do is help us understand what has happened. And for me, this is good enough. As someone once said, "Economists have only changed the world; the point, however, is to understand it."

* The Origin of Wealth is like Marx's Capital or Kahneman's Thinking Fast and Slow; it gets a lot better once you get past the first 50 pages or so.

December 30, 2014

The diversity paradox

Listening to Lenny Henry on the Today programme this morning, I was reminded of a paradox about diversity.

What I mean is that there are (at least) three distinct meanings of the term. One is ethnic and gender diversity - ensuring that women and minorities are fairly represented in positions of power and prominence. A second is cognitive diversity - giving space to different intellectual perspectives. And a third is ecological diversity: having a variety of strategies and business models.

I would argue very strongly for diversity in the last two senses.A multiplicity of perspectives - or epistemological anarchism in Paul Feyerabend's words - can be a solution to the problems of (tightly) bounded knowledge and rationality; this is expressed mathematically in the diversity trumps ability theorem. And ecological diversity can protect economies from shocks: the 2008 crisis was so severe because there was a lack of such diversity in the financial sector because many banks were following similar strategies. In a changing environment, mixed strategies help ensure survival.

A big reason why I support gender and ethnic diversity is because I favour these other forms of diversity. There's evidence that ethnic diversity can promote innovation and productivity, probably because it contributes to diversity in these other senses.

Which brings me to my paradox. My support for all three types of diversity is, I fear, not widely shared. Quite the opposite. Whilst there is widespread support in words (if not deeds!) for ethnic diversity, some of the dominant trends of our time are working against diversity in the other senses. For example:

- The main political parties have become more homogenous in the sense both of squeezing out mavericks and in the sense of becoming increasingly dominated by career politicians to the exclusion of people from working class backgrounds.

- Managerialists' attempts to impose hierarchy and targets onto all organizations are an attack upon ecological diversity.

- Social media might have exacerbated the trend towards groupthink, in which dissonant views are shouted down.

- There's a variety of perfectly coherent views which are far less heard than their merits would warrant: Oakeshottian conservativism, small state Keynesianism, left Hayekianism and so on.

Such conflicting attitudes to the different concepts of diversity are evident on the Left. Lefties have been happy to call for more ethnic diversity whilst fiercely opposing free schools - though the latter, insofar as they have merit at all, are an example of ecological diversity.

Not that the vice is confined to the left. I suspect that those "socially responsible" bosses who want to promote women and minorities in their firm often do so by hiring those who think just like them - thus achieving ethnic diversity at the expense of cognitive diversity.

All this brings me to a variant of the question asked by Nkem Ifejika: what's the point of having so many ethnic minorities in positions of power and prominence if nothing else changes?

Mr Henry replied that doing so would level the playing field. That's reasonable insofar as it goes. But given that equal opportunity and social mobility are such weak ideals, I fear that it grossly undersells the potential benefits of diversity.

December 18, 2014

The fiscal-monetary mix

In my previous post, I pointed out that, given the inflation target, a less tight fiscal policy implies higher official interest rates. This means that the choice between the two main parties isn't just about fiscal policy, but about the fiscal-monetary mix: Labour offers looser fiscal and tighter* money than the Tories. Which poses the question: what should be the right mix?

Simon is, of course, right:

It is stupid to commit to further significant fiscal contraction (‘austerity’) when interest rates are still at or close to their lower bound. It means we become more vulnerable to adverse shocks to demand.

Let's suppose, however, that the OBR's forecasts are right and that the economy can grow decently and that inflation will rise even with a tight fiscal policy: this is, of course, a strong assumption as economies are inherently unforecastable. If this is the case, we might well be pulling away from the zero bound midway through the next parliament; markets are pricing in a 1.5% Bank rate by 2017.

Which poses the question: what should be the policy mix then? If we could achieve the same growth and inflation with different fiscal-monetary mixes, which mix should we prefer?

The argument for fiscal tightness is straightforward. We need to stabilize or reduce the debt-GDP ratio sometime. Intergenerational equity counts for something, and there's a risk that global real interest rates will trend up, adding to debt service costs. There's also a case for raising real interest rates: a long period of low rates risks creating a social norm against saving.

There are, though, three issues here.

1. Inequality. For a given level of unemployment, loose money and tight fiscal policy might generate more inequality. This is because loose money raises the prices of assets, which are - by definition - held by the rich. Also, the burden of fiscal austerity is likely to fall upon welfare claimants. (Yes, many of the poor are in debt - but the interest rates they pay aren't related to Bank rate.)

This, though, isn't a knockdown argument. If a loose money/tight fiscal mix does have adverse effects on equality, the solution lies in changing taxes and benefits - not necessarily in altering the policy mix.

2. Secular stagnation. If low interest rates stimulate productive capital spending, they are to be welcomed. However, if there's a dearth of monetizable investment opportunities, low rates might instead fuel bubbles and malinvestments. In such a world, looser fiscal policy might be preferred precisely because it would crowd out the private sector.

Again, though, it's not clear how relevant this is. On the one hand, the housing market seems to be cooling and the stock market isn't in a bubble: if it were, I'd have retired by now. But on the other hand, the fact that business investment fell in Q3 suggests that real investment opportunities might still be limited.

3. Practicality. One argument against a sharp tightening is that it implies cuts in public spending which are too big to be credible. A slower pace of cuts would have the virtue of giving the government time to research ways of improving efficiency; make the organizational changes which could deliver services more cheaply; and create more of a political consensus on which functions the state should relinquish.

Now, I don't have especially strong views here. Which is my point. The best fiscal/monetary mix depends upon the context. As Edmund Burke said:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour and discriminating effect.

I can easily imagine circumstances in which I would be on the side of some sort of fiscal austerity; my opposition to austerity so far has been because the circumstances aren't right for it.

I fear, though, that my view is a minority one and that many others' positions (on both sides) are more fixed. But then, that's the thing about us Marxists - we are so much less dogmatic than others.

* By tighter money, I mean a higher real Bank rate. I find arguments about the definition of "tight" money tiresome.

December 16, 2014

Deficits & interest rates

I fear that the argument between Robert Peston on the one hand and Simon, Paul and Alex on the other about the relationship between government borrowing and interest rates is understating something important.

I agree with Robert's critics that interest rates are not determined by bond vigilantes or confidence fairies - at least for the UK at current debt levels. But there is a different reason to think that a looser fiscal policy would lead to higher rates.

Quite simply, looser fiscal policy would lead to higher aggregate demand and hence to a smaller output gap. If you believe - as the Bank of England does - that a smaller output gap leads to more inflation (or at least the risk thereof) then this means higher interest rates will be needed to hit the inflation target. And because gilt yields should be equal to the expected path of future short rates, it follows that a looser deficit should mean higher yields.

Paradoxically, the more Keynesian you are, the more you should accept this. If you think fiscal multipliers are very big, then looser fiscal policy means much bigger aggregate demand and hence - given the Bank's remit* and view of the inflation process - significantly higher rates.

In this sense, the choice is not just about fiscal policy but about the fiscal-monetary mix. Labour is offering looser fiscal and tighter money than the Tories.

In this context, David Cameron said something yesterday that's misleading. It's this:

By 2018 we will be putting money aside so that if any crash or shock happens to our economy, we will be better prepared.

Now, it might be that a tighter fiscal policy now would give us more room for fiscal manoeuvre when the next recession hits. But the counterpart of a tighter fiscal policy is that interest rates will stay close to the zero bound - which will give us less room for monetary manoeuvre in future. It's not obvious which is best.

One could easily argue - though I'll save this for another day - that a looser fiscal/tighter money policy is preferable. It's entirely coherent to say: "Interest rates would be higher under a Labour government - and a damned good thing too."

Herein, though, lies a puzzle. If Labour's policy implies higher interest rates, why aren't we seeing more volatility in gilts as market opinion about the election outcome varies?

One possibility is that there won't in reality be much difference between the two parties' fiscal policies simply because the Tories' stated plans are nonsense: four-fifths of macroeconomists agree with Rick that their spending plans are in la-la land.

Another possibility is that interest rates won't rise much whoever controls fiscal policy, as they'll be held down by some combination of secular stagnation, deflation and stagnation in the euro area and (very arguably) falling oil prices.

These two possibilities hint at something else - that perhaps the debate about the impact of the deficit upon interest rates isn't very important for practical purposes.

* Those who argue for a serious reflationary policy should be calling not just for looser fiscal policy but for a change to the inflation target too (and of course many are).

Another thing: Robert's "fey anthropomorphism" of the market is mistaken. The "Mr Market" metaphor can sometimes be horribly misleading.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers