Chris Dillow's Blog, page 112

November 1, 2014

The heritability red herring

Here's an example of how the right are in denial about inequality.Responding to a report in the Telegraph that the offspring of parents with a degree go on to earn more than the children of less educated parents, Tim Worstall says:

What we’re seeing is that the children of the rich and or bright have higher incomes than the children of the not rich and not bright. And put that way it’s not really all that surprising, is it?

This, though, is only part of the story. Heritability of ability can explain why the children of rich and bright parents go on to earn more than the children of the poor and not bright. But it cannot explain why this tendency is stronger in some countries - such as the UK and US - than in others.

We'd expect genetic heritability to be roughly equal across countries. But intergenerational mobility is not: it is lower in Germany than Finland, and lower still in the US and UK. Why should ability be more heritable in the UK than Germany and more heritable in Germany than Finland? Tim gives us no reason to think it is.

Instead, what we have here is the so-called Great Gatsby Curve - a cross-country correlation between inequality and intergenerational income mobility.

The research reported in the Telegraph - to which Tim does not link - tries to explain this. John Jerrim and Lindsey Macmillan show (pdf) that three things other than heritability are at work:

- The correlation between parental education and children's education is higher in more unequal countries. This is consistent with income inequality buying unequal access to education - for example, because rich parents in unequal countries buy private tuition.

- The returns to degrees are higher in unequal countries such as the UK and US than in more equal ones. This magnifies inequality in access to higher education.

- In the UK, children of uneducated parents earn less than the children of educated ones, even if they have the same qualifications. This suggests that inequality operates through channels other than education - for example by nepotism and cronyism excluding state school kids from top jobs.

It's clear from Jerrim and Macmillan's work that the retort "it's coz ability is heritable innit" is inadequate.

This, of course, matters. It means inequality is - to a greater extent that Tim admits - a social construct rather than an artefact of nature.

Now, I stress that I don't say this merely to have a pop at Tim; for the purposes of this blog, individuals matter only to the extent that they exemplify social or intellectual phenomena. I fear, based upon some of the comments to his piece and (some of) the right's past form, that he is exemplifying a more general habit - a kneejerk denial of the costs of inequality based upon glib appeals to human nature and a reluctance to actually engage with research.

Another thing: if I were a rightist trying to justify inequality, I'd argue instead simply that intergenerational immobility is no problem.

October 31, 2014

Against evidence-based policy

What is the case against evidence-based policy? This is one question prompted by David Cameron's refusal to legalize drugs in the face of evidence that criminalization of them doesn't reduce their use.

The question, of course, generalizes. Many of us would argue that fiscal policy and immigration policy are also less than perfectly based in the evidence - and no doubt you can think of other examples. There must, therefore, be something to be said against evidence-based policy. But what?

One answer lies in something we know from financial decision-making - that greater knowledge doesn't necessarily improve the quality of decision-making. It might instead merely increase people's overconfidence and so magnify their mistakes.

This matters because in a complex world there is inevitably a lot that cannot be known about effects of policy, particularly in the long-run and about the possible effects of policy upon social norms. For example, whilst there is good evidence that immigration doesn't reduce wages on average, and might even increase them, there is - as Diane says - rather less hard evidence about their long run effects. Might it be that, in the long-run, a more ethnically heterogenous society would lead to greater tolerance of inequality? Or take tax policy. There might (pdf) be some evidence that higher taxes on top earners would, in the short run, raise revenue. But what about the possibility, stressed by Assar Lindbeck, that redistribution might in the long-run erode social norms in favour of work?

There's a lot that cannot be known about policy effects. Stressing the need for evidence might therefore cause us to overweight partial knowledge and so lead us astray.

I'd add three other arguments:

- Evidence-based policy is, necessarily, conservative simply because there's no available evidence one way or the other about the effects of truly radical policies. For example, would a high citizens' income or market socialism work? As they've not been tried, we can't know.

- If we are to base policy upon evidence we will have to override the public's preferences in many policy areas, simply because these are founded upon egregious errors. Whilst there is a case for doing this there is also a danger. Excluding the public risks increasing elitism and undermining the democratic spirit. Ignoring people's preferences might lead to a slippery slope in which governments eventually ignore people.

- Instrumental rationality is not the only rationality. As Robert Nozick said, there is is also symbolic rationality; we do some things not because they fit a narrow cost-benefit calculus but because they symbolize who we are. We might want to criminalize drugs to express our abhorrence of wasting lives to addiction; or we might favour minimum wages even if they destroy jobs to symbolize our distaste for low pay; or we could subsidise inefficient green energy to express our concern for the climate. And so on. Whatever you think of these examples it would surely be rash to dismiss symbolic motives entirely, given that it is otherwise hard to understand why people vote or protest.

Now, I'm not sure how strong these arguments are. I mention them because both main parties attitudes to (say) immigration and fiscal policy are not based in evidence. Which must mean that there is some sort of argument against evidence-based policy.

October 29, 2014

"A culture of mistakes"

The Sunderland Echo has a useful phrase - a "culture of mistakes". In fact, such a culture extends far beyond the Mackems. In a world of complexity, bounded rationality and limited knowledge, mistakes are inevitable and ubiquitous. The question, therefore, is not merely how to avoid them but rather: which ones should we make?

This question arises in countless contexts. Football teams must choose between playing from the back and so risking the mistake of giving the ball away in a dangerous area against playing it long and so making the more common but less costly mistake of conceding possession in less dangerous areas. Central bankers must compare the mistake of raising unemployment against the mistake of letting inflation rise; the notion of a central bank loss function is central (pdf) in macroeconomics. Social workers must compare the mistake of breaking up families unncessarily against the mistake of exposing children to danger. Medical diagnosticians must compare the mistake of false positives (seeing a disease where none in fact exists) against that of false negatives (failing to diagnose a disease where it does exist). And so on.

There is, however, one profession that seems to be an exception here - politics. Although mistakes are as common in politics as elsewhere, politicians rarely ask voters: which errors would you rather we made?

And yet this question is central to many policy areas. For example, in civil liberties we must weigh the mistake of risking an avoidable terrorist attack against that of curtailing freedom unnecessarily. Taxation policy must weigh the mistake of possibly permitting excessive inequality against that of perhaps reducing incentives to innovate. Benefit reform must weigh the mistakes of giving some claimants too much and others too little against the administrative errors that are inevitable when you try to change a massive and complex system. And so on.

AFAIK, though, no minister has said: "There will be mistakes in this policy. It's just that it's better to make the mistakes associated with this than the errors associated with other courses of action."

You might reply that this is because if they did so, they would be slaughtered by the media. Maybe so. But this merely confirms what I've said before - that the problem with our politics lies not (just) with our politicians but in our broader political culture which is too immature to recognise that the real world is more complex than human abilities can handle.

October 28, 2014

On false consensus

Last night, we saw a great example of how cognitive biases can have catastrophic effects when Corrie's Rob confessed to the World's Most Perfect Woman that he had killed Tina.

I suspect he did so because of the false consensus effect - our tendency to over-estimate the extent to which other people are like us. Because he knew that he'd killed Tina, he mistook the WMPW's suspicions for hard knowledge and so broke down in the false belief that he couldn't sustain his denial: the fact that he wanted the WMPW to keep quiet about the murder suggests this, rather than a Raskolnikovian urge to repent, was his motive*.

I sympathize with Rob here, because I am prone to the false consensus bias myself. For years in the day job I've been surprised when fund managers talk about behavioural finance as if it's a new thing: "surely everyone knows that", I've thought. And one reason why this blog is so badly written is that I tend to assume that others share my presumptions and knowledge to a greater extent than they do, and so I fail to explain things fully.

There's also good academic evidence for the false consensus effect, for example:

- It can cause people not to vote, because they believe - perhaps wrongly - that others think the same way as them and so their vote won't make a difference. This might explain why Thom was voted out of Strictly Come Dancing on Sunday.

- Trustworthy people over-estimate the extent to which others are trustworthy, and so lose money.

- Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi have shown that tall people over-estimate how many other people are tall; left-wingers over-estimate the prevalence of left-wing opinion; onwers of HTC phones over-estimate their popularity, and so on.

I'm pretty clear, then, that the false consensus effect is widespread. What I'm not so clear about is whether it has whether it has significant costs. I suspect it might, in (at least) three ways:

- It might cause us to under-estimate principal-agent problems because we exaggerate the commonality between ourselves and the agent. This might cause shareholders (or workers!) to insufficiently rein in chief executives, and cause us to become too optimistic about the extent to which politicians will act in our interests.

- It'll cause us to under-estimate the benefits of cognitive diversity. If we believe that everything thinks like us anyway, we'll not invest in ensuring we get a plurality of perspectives and we'll be overly inclined to trust hierarchical decision-making processes.

- We'll under-estimate the divisions between rich and poor. Paul Krugman has pointed out that the rich are invisible, in the sense that ordinary people under-estimate (pdf) just how wealthy they are. This is an example of the false consensus effect; people over-estimate the extent to which others are like themselves. But of course, it's not just ordinary folk who do this. The rich probably fail to see how the worse off struggle to get by.

Now, I know I risk sounding like a one-trick pony, but might there be a common theme here? Perhaps the false consensus effect - to some extent at least - is one of the many factors which helps to sustain hierarchy and inequality.

* Anyone who thinks it odd to mention Corrie and Dostoyevsky together is, of course, not the sort of reader I want.

October 27, 2014

Our distorted priorities

There's something I find depressing about the response to my post on Russell Brand - that it has received far more attention than almost all my other posts even though many of those are on what I'd regard as more important matters.

Now I know that writing about your blog traffic is, to paraphrase Lyndon Johnson, like pissing down your leg: it seems hot to you, but it never does to anyone else. But bear with me, because I fear that this pattern illustrates (at least) three depressing facets of our political life. (I might be committing the journalist's fallacy of drawing general inferences from particular data here, but I'll risk it.)

One is tribalism. As I've said before, people aren't really interested in politics in the sense of how our public realm should be governed. Instead, their interest in politics is merely tribal; they want to cheer their own tribe whilst booing the other. Attitudes to Russell seem unduly influenced by whether one regards him as one of us or one of them.

A second is that we live in a celebocracy. People want to read about celebrities; my post on Owen Jones also got disproportionate traffic. As Matt says, the left is at least as guilty here as the right. There's a long and largely inglorious history of leftists looking for heroes who in fact are deeply flawed.

Thirdly, people take their agenda from the media; I've often noticed higher than usual traffic when I blog about "newsworthy" matters.

Now, I don't say all this merely to deplore such trends. I'll confess to my share of tribalism and celeb-interest too: I spend more time than I should on Popbitch and the Mail's sidebar of shame.

Instead, my concern is that these tendencies, if unchecked, serve a reactionary purpose. The media-celeb-tribalism agenda serves as an Overton window, allowing light to shine on some issues but not others. But it's those other, endarkened, issues that truly bring into question the desireability of our existing order. My recent posts on social mobility, intellectual diversity, attitudes towards inequality and the constraints upon leadership are more important than my posts on Brand and Jones, and have more radical implications too. But because they fell outside the Overton window they were (relatively) neglected.

If we had a political culture that was seriously interested in social change, it would pay less attention to Russell Brand and much more to the Smith Institute report (pdf) on working conditions and Stuart White's piece on liberal responses to inequality - to take two very recent examples. But it doesn't. And that is an obstacle to egalitarian change.

I say all this not to expect you to give a damn about my blog's traffic - I don't, so why should you? - but to raise a question. It's a cliche to complain about politicians. But could it be that many of the problems with our politics lie not just with their inadequacies, but rather in the fact that even those voters who claim to be interested in politics have a distorted sense of what's important?

That poem by Bertolt Brecht is a terrible cliche, but it hints at some truth.

October 26, 2014

Russell Brand & our political culture

Everyone has been having a pop at Russell Brand. Focusing upon his foibles, however, serves to distract us from some fundamental defects of our political culture.

Take these quotes from him:

The economy is just a metaphorical device, it’s not real, that’s why it’s got the word con in it.

I’m not supposed to get my head around economics, none of us are, it’s designed to be obtuse. Look at those f***ing NASDAQ, FTSE, Dow Jones things...

I ain’t got time for a bloody graph… This is the kind of stuff that people like you use to confuse people like us.

These show that Sunny is right: Brand represents "anti-intellectualism on an epic scale".

Which poses the question: why, then, is he not being simply ignored as we would any other embarrassment?

Part of the answer is that we live not in a meritocracy but a celebocracy. Brand hasn't got a big publishing deal, acres of publicity and an invitation onto Newsnight because of the brilliance of his ideas but simply because he's a big celebrity - and as Nick says, TV bosses believe that the punters want celebs with everything.

In this respect, Brand is, well, a powerful brand. He is - in those words which Shoreditich twats regard as terms of commendation and the rest of us as a red light warning of undiluted bullshit - "cool and edgy". TV execs want him for the same reason middle-class teenagers go on gap years to Thailand or on Duke of Edinburgh award schemes; he offers a slight frisson of peril without actually offering any serious danger; I suspect this also helps explain Nigel Farage's appeal to the BBC.

It would, however, be silly to pretend that Brand is unique in his anti-intellectualism. Our ruling class - which includes the BBC and Labour party as well as the Tories - have created a hyperreal economy which obsesses over non-problems such as "the deficit" and immigration to the exclusion of truth and intellectual effort.

But the left is also at fault here. The question which Brand cannot answer - "replace capitalism with what?" - is also one to which it has little answer.

Any serious revolution would, of course, disempower political and business elites and empower people. Which raises many questions: why is there so little popular demand for worker management or even direct democracy? How do we promote anti-managerialism? Could we achieve worker democracy without weakening incentives to innovate? What institutions do we need to create a healthy deliberative democracy rather than debased populism?

Of course, people have been working on questions such as these for years but their efforts have, to put it mildly, not greatly entered the mainstream of the British left. Instead, as I complained nine years ago, much of the Left seem to prefer slogans and self-righteousness to serious thinking.

Just as some plants thrive in arid conditions, so Russell Brand thrives in our intellectual desert. Pointing to the ugliness of this plant, however, should not distract us from the fact that our biggest problem is our anti-intellectual political climate.

October 23, 2014

Immigration & capitalism

John Harris writes:

Perhaps those who reduce people’s worries and fears [about immigration] to mere bigotry should go back to first principles, and consider whether, in such laissez-faire conditions, free movement has been of most benefit to capital or labour.

Let's do this. Here are some first principles:

- Factor price equalization. Foreign workers can bid down British wages through trade. Whether they come here or not, their effect on wages is much the same.

- Complementarities. Some foreign workers are complements for native ones, and so raise wages of the latter. For example, Polish roofers allow British plasterers and electricians to do more work.

- Adjustment. Insofar as immigrants do reduce wages, this will also reduce prices. This allows interest rates to fall, which boosts demand for labour and hence wages. Also, a drop in the price of labour relative to capital should lead to rising demand for labour relative to capital. On both counts, labour demand should increase, thus reversing the initial adverse impact of immigration.

These principles imply that free movement won't much tilt the balance between capital and labour.

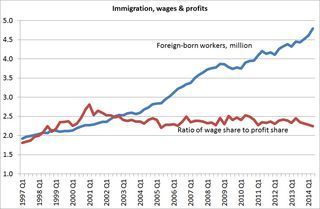

In the unlikely event of anyone wanting empirical evidence, my chart provides some. It shows that the ratio of the wage share in GDP to the profit share hasn't much changed in the last 10 years even though the number of foreign-born workers has risen. In fact, the wage share is higher than it was in 1997, even though the number of foreign workers has almost doubled. This is consistent with our first principles.

Now, some people might be surprised by the stability of the wage share. If the wage share hasn't changed, how come real wages have fallen and so many workers are struggling?

Simple. Workers aren't suffering because the balance of class power has shifted to capital. There are (at least) three other things going on, on top of unnecessarily tight fiscal policy:

- Job polarization. The number of decent middling jobs is falling, relative to low-paid ones.

- Decorporatization. There's been a shift from the corporate sector to the self-employed. This has squeezed profits and - to the extent that they are in part a share of economic rents - wages too.

- Falling productivity. Output per worker-hour is lower now than it was in 1997 - in part, perhaps because of lousy management (pdf). A smaller pie means less for everyone.

Wages, then, are being squeezed not by immigrants, but by some fundamental trends in capitalism.

In this context, the "modern left" that Harris sneers at should be a lot angrier than it is. Those who seek to link immigration with falling living standards are guilty not just of (perhaps wilful) ignorance. They are trying to shift the blame from capitalism to some of the least powerful members of society. That's not just racist. It's fascist.

October 22, 2014

Persuasion with statistics

Mark Thoma's point that apparently strong econometric results are often the product of specification mining prompts Lars Syll to remind us that eminent economists have long been wary of what econometrics can achieve.

I doubt if many people have ever thought "Crikey, the t stats are high here. That means I must abandon my long-held beliefs about an important matter." More likely, the reaction is to recall Dave Giles' commandments nine and 10. (Apparently?) impressive econometric findings might be good enough to get you published. But there's a big difference between being published and being read, let alone being persuasive.

This poses a question: how, then, do statistics persuade people to change their general beliefs (as distinct from beliefs about single facts)?

Let me take an example of an issue where I've done just this. I used to believe in the efficient market hypothesis. And whilst, like Noah, I still think this is good enough for most investors' practical purposes - index trackers out-perform (pdf) most active managers - I now believe there are significant deviations from the hypothesis, one of them being that there is momentum in share prices: past winners carry on rising and past losers continue to fall.

How was I convinced of this? As Campbell Harvey and colleagues point out, there are huge numbers (pdf) of patterns in the cross-section of returns. Most (though not all) leave me cold. Why has momentum been an exception?

There were two general things that persuaded me of this.

The first was evidence from different data sets. When I first encountered the case for momentum in Jegadeesh and Titman's paper, I merely thought: "that's interesting. I wonder if it applies elsewhere." So I set up a very simple hypothetical basket of momentum stocks for the UK - and found that it too has out-performed over long periods. And there's since been evidence that momentum effects exist in currencies, commodities, international stock markets and in 19th century markets.

The fact that different data say the same thing is something I found persuasive.

Secondly, there's powerful theory explaining momentum - all the more so because there is more than one theory.

One such explanation is simply that investors under-react to good news, causing shares to drift up rather than - as the EMH predicts - fully embody the good news immediately. This is intuitively plausible because casual empiricism tells us that Bayesian conservatism is widespread. But it's also consistent with another finding - that there's post-earnings announcement drift.

But this is not the only potential explanation. Another is that people have limited attention; some things escape their notice, so they might not spot when some stocks enjoy good news. This is consistent with the finding that that shares which see steady drips of news have stronger momentum effects than those which get a big splash of it.

And then we have an explanation for why smarter investors don't eliminate these irrationalities. Victoria Dobrynskaya has shown that momentum strategies have the wrong sort of beta: high downside beta and low upside. This means they carry benchmark risk - the danger of underperforming the general market. This makes them unattractive to those fund managers who fear being punished for under-performing.

My point here is, perhaps, a trivial one. The above is not a story about statistical significance (pdf). Single studies are rarely persuasive. Instead, the process of persuading people to change their mind requires diversity - a diversity of data sets, and a diversity of theories. Am I wrong? Feel free to offer counter-examples.

October 21, 2014

Facts, & the Establishment

Jeremy Duns accuses Owen Jones of some factual errors. Insofar as he's right, this actually strengthen the substance of Owen's big contention - that the Establishment is a self-regarding clique.

Owen's errors are not decisive ones; the claims he has got wrong are not load-bearing ones. Nobody is going to think "So, the DESO doesn't exist any more. This shows that there's no such thing as crony capitalism." In pointing out his errors, Jeremy is not so much defending the Establishment as attacking Owen.

Let's grant, for the sake of argument, that he's right - that Owen is using wrong or misleading claims, possibly deliberately, to stir up hatred. (I stress that I don't actually believe this. I just want to see where the worst-case characterisation of Owen leads us.) If this is so, all Jeremy has done is show that Owen is well-qualified to enter the House of Lords.

And what's more, he hardly unique in being careless with facts. The Establishment itself lies about the economy and welfare state, ignores key facts about migration, and rests for its support in part upon public ignorance. Being stupid little shits is a good career move in the Establishment - just look at Richard Littlejohn, Toby Young or James Delingtwat. It would be odd, therefore, to single out Owen.

And let's just ask. If Owen is so bad, why did one of the UK's biggest publishers commission him to write a book?

The answer lies on his Twitter page. He's got 222,000 followers. That's a big market. He's got a book deal for the same reason Russell Brand has - not because of his intellect or command of his subject but because he sells.

Which brings me to the point. If you believe the worst about Owen, then it corroborates those of us who fear that we live not in a meritocracy but in a celebocracy, in which fame - however ill-merited - begets more wealth and acclaim and in which intellect and honesty are unimportant. But this self-perpetuating, closed elitism and post-truth politics is exactly how some of us would characterize the Establishment.

October 20, 2014

Social mobility in a dystopia

I have long been sceptical of the feasibility and desireability of social mobility. Today's report by the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission, though, makes me wonder: is social mobility an out-dated idea?

To see my point, imagine two different societies. One is a bourgeois society, comprising a mass affluent middle class alongside some poverty. The other is a winner-take-all society in which the 1% enjoy huge incomes whilst the 99% just get by.

Now, the Milburn Commission's recommendations make sense for a bourgeois society. Improving the educational opportunities of the poor and their pathways into work would increase their chances of entering the legions of mass affluent.

But I'm not so sure they make so much sense for a winner-take-all society. In such a society social mobility will, by definition, be limited: only 1% of people can be in the top 1%. And whilst better education might increase one's chances of entering the 1%, it does so in the same way a lottery ticket increases your chances of becoming a millionaire: without it, you have no chance and with it only a slim one.

More likely, in this society, a degree would only equip you for some type of poorly paid or poor quality job. And it might even accelerate the degradation of previously middle-class jobs by increasing the supply of graduates faster than the demand for them.

And here's the problem. If you believe the pessimists about the impact (pdf) of robots or Pikettyan-type forecasts of the growing wealth and income of the 1%, we might be moving towards a winner-take-all society.

If they are right, the Milburn Commission's ideas to improve social mobility might be another example of ideas that have outlived their usefulness. They might make sense in the context of an economy in which there are high and stable returns to education - that is, the sort of economy which New Labour thought characterized the 1990s - but they are not so relevant to a world in which technical change, superstar effects and/or rigged markets generate a 99%/1% economy. In such an economy, Simon Kuper might well be right: social mobility should be a lesser priority than equality and community.

Now, I don't say this to endorse the dystopian futurology of the Pikettyans and robot-fearers. My point is rather that one's view of the desirability of social mobility, and one's proposals to increase it, must surely be founded upon some theory about the shape and determinants of inequality. And it's not obvious that the Milburn Commission has the right theory.

Another thing: I don't say this to completely rubbish the report. Its merits rather lie in its call for redistribution (a living wage) rather than in its policies towards social mobility.

Yet another thing: when Simon says that upward mobility entails loss and loneliness he is hugely and importantly correct. It is, ahem, ironic that politicians should fret so much about the loss of social cohesion due to immigration and yet want more social mobility even though this too would reduce that cohesion.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers