Chris Dillow's Blog, page 116

September 15, 2014

The costs of poshos

Nick Cohen has brilliantly described how the arts and media are becoming dominated by public school products to the exclusion of people like us. This makes the irrational class-hating part of me - which is the biggest part - want to take up arms. But the rational bit of me wonders: what exactly is the problem here?

I don't think the problem is that talent is being wasted. Maybe it is, but having a few jobs done by second-rate public schoolboys rather than first-rate state school ones is surely a second-order cost. Remember that the single individual who's probably done most damage to the economy in recent years - Fred Goodwin - went to state school.

Nor even is there a huge injustice here. The financial payoffs to acting and journalism are on average small (and in journalism the non-pecuniary rewards are even smaller). Forcing bright state school people out of acting or the media and into other professions might even be doing them a favour. The biggest injustice isn't what happens to clever state school kids after 18, but rather the fact that people from poor backgrounds are much less likely to go to good universities than the rich, and that unqualified people suffer unemployment or poverty wages.

Instead, I suspect that there's another cost of having public school people dominate the media and arts. It's that this domination produces systematic ideological distortions.

For example, a Dulwich-educated stockbroker who wants to destroy workers' rights is presented in the media as a man of the people. And a man who consorts with a violent criminal and who has twice been sacked for dishonesty is spoken of as a potential Prime Minister. Such an inversion of common sense is surely facilitated by a media which regards public school backgrounds as normal and therefore unthreatening. The BBC's three most senior political reporters (Norman Smith, James Landale and Nick Robinson) were all privately educated; I suspect this imparts a bias, consciously or not.

Secondly, a media which is dominated by people from posh backgrounds is prone to over-estimate middling incomes; if you, your family and friends are on six-figure salaries, you'll regard these as more normal than they in fact are. This can lead to the interests of the well-off being wrongly conflated with those of the average person, which the result that political discourse is biased towards the interests of the rich.

Thirdly, an arts establishment dominated by the well-off is less able to portray the realities of life for the poor.

To see what I mean, picture the 1930s depression. If you're like me, your visual images come from Steinbeck and Orwell, and the aural ones from Woody Guthrie and the Carter Family. Picture the 1980s recession, and we (I?) recall the Specials, Brookside and Boys from the Blackstuff. Now picture the recent Great Recession. What do you see? What do you hear?

Nothing. Culturally, the recent recession didn't happen. And this is perhaps not unrelated to the fact that people from poor backgrounds - with the sensibilities this implies - are excluded from the arts establishment.

I'm tempted, therefore, to claim that there are costs to having the arts and media dominated by public schools.

Except that is, for one thing. Capitalism tends to produce false perceptions in people anyway; it sustains itself in part by producing an ideological bias. A public school establishment might contribute to this bias. But it would probably exist even without their efforts.

September 14, 2014

"Same policies work everywhere"

Back in the day, a concatenation of circumstances led to me being alone in a room with a well-known economist who was then advising governments around the world. I thought I'd start the conversation with the anodyne remark "it must be a fascinating challenge to give policy advice in so many different places."

"No", he replied. "The same policies work everywhere."

I was surprised by this. One of us is wrong here, I thought, and if it's me, at least nobody is getting hurt.

I was reminded of this by this Venn diagram, reproduced by Tim.

The diagram's force rests upon the belief that the same policies work everywhere - that a price rise has the same effect in all markets.

But this is precisely what advocates of higher minimum wages question. One argument for them is that a higher price of labour won't reduce demand - because employers have monopsony power, or because higher wages will be offset by lower turnover.

This highlights two different ways of thinking about policy, pointed out by Edmund Burke, as discussed (pdf) by Jesse Norman.

On the one hand, he said (par 12 here), there is "the nakedness and solitude of metaphysical abstraction". The Venn diagram depends for its power upon this way of thinking - that the abstractions of Econ 101 work everywhere.

Burke, however, rejected this:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.

From this perspective, Krugman and other advocates of minimum wages are making a reasonable point. The circumstances of labour markets are not the same as those of carbon markets, so political schemes that are beneficial in the one can be noxious in the other.

Now, I don't say this to defend minimum wages. I think a much better way to help the low-paid would be to strengthen their bargaining power via policies such as expansionary macro policies, a serious jobs guarantee, a basic income and stronger trades unions. Instead, I do so to point out that if you wish to argue against minimum wages you must counter the monopsony-style arguments.

Snarking about inconsistency might be good enough for Oxford Union-style debating knockabout. But it's not serious economics. And- given the Burkean dichotomy - nor is it good philosophy.

September 12, 2014

The referendum, & risk attitudes

To what extent is the Scottish referendum about the benefits of independence and to what extent is it about people's attitudes to risk?

To see my question, think of independence as an investment with a risky payoff - which is what it is.

There are two reasons why one might reject such an investment. One, trivially, is simply that you expect a negative payoff. The other is that you expect a positive payoff but think the risks around it are too high.

It is perfectly possible for two people to agree upon payoffs and risks and yet one would accept the proposal and the other reject it because one is more risk-tolerant than the other. This is commonplace in asset allocation. Two investors might agree upon expected returns and volatility and yet one might hold more equities and fewer safe assets than the other simply because of differences in tastes.

Mightn't the same be true for many people for Scottish independence? Two Scots might agree on the payoffs and risks to independence but one might vote yes and the other no because of differences in risk tolerance.The statement "Independence probably would be a good thing, but I don't want to risk it" seems tenable to me.

There's an analogy here with the Duhem-Quine thesis. Just as experiments are usually tests of joint hypotheses, so too are referenda; they test attitudes to risk as well as expected payoffs.

One fact lends credence to this. It's that women seem more inclined to vote no than men. For example, the latest YouGov poll shows men 51-44 in favour of independence but women 39-55 against. I don't see why men and women should have different knowledge about the effects of independence. But I do know that there's evidence that women tend to be more (pdf) risk-averse than men. And this would tip more into the no camp*.

Now, this isn't decisive. There's less evidence for gender differences in uncertainty-aversion - and this (unknown unknowns) might be more relevant than risk-aversion (known unknowns) to the vote.

Nevertheless, it's possible that in a tight contest the referendum might be decided not just by the merits or not of independence, but by attitudes to risk. A no vote might tell us not that independence is a bad idea, but that it's a good one but some Scots are too risk-averse to chance it.

If I'm right, there are some implications.

One is that, from a nationalist point of view, autumn is the wrong time for a referendum. We know from the stock market that risk appetite is seasonal; it's high in the spring and low in autumn - which is why the "sell in May, buy on Halloween" rule usually works so well. Because the Nats want a high appetite for risk, they should have gone for a spring vote.

However, all is not lost for the Nats. There's also some evidence that risk appetite is affected by the weather - it's higher in sunny days than wet ones. If the Indian summer lasts into next week, it could tip some into the yes camp. Not many, granted - but in a tight vote, even small influences count.

Secondly, if Scotland does vote no, the Nationalist cause won't die. Everyone has immunizing strategies which protect their cherished beliefs from challenge. Nationalists could claim not that Scots believe independence to be a bad thing, but that some were too risk-averse to go for its benefits. It'll be very difficult to refute this.

* Whether this is because of nature or nurture is moot but irrelevant for my purposes.

September 11, 2014

How Scotland should decide

Whatever the result of the Scotish referendum, almost half of all Scots will be disappointed, some very much so. Would there have been a better way of arranging things?

Possibly. I'm thinking of a demand-revealing referendum. The idea here is simple. Rather than simply put an X in the yes or no box, voters are asked to state the monetary value they would put upon independence; for nationalists this would be a positive amount, for unionists a negative one. And then, we look at whether any individual's vote was big enough to change the outcome, and levy upon him a tax equal to the net gains the other side would have had in the absence of his vote.

Take an example with three voters. Alec would vote £100 for independence, Bruce would vote £30 for no, and Charlie would vote £40 for no.

As £100 beats £40 + £30, independence wins. However, because Alec's vote is decisive, he must pay a tax of £70 - the net gains Bruce and Charlie would enjoy has Alec not voted.

The beauty of this system is that it forces people to express their true feelings. If you vote too big a sum you risk having to pay a big tax, whereas if you vote too little you risk not getting your way.

This procedure is consistent with the greatest happiness of the greatest number. In our example, independence is a potential Pareto improvement, in that Alec could in principle compensate Bruce and Charlie and still be better off*. By contrast, simple majority voting allows the weak preferences of the many to outweigh the strong preferences of the few.

In this sense, utilitarians should prefer a demand-revealing referendum to a simple one.

I'd add two further benefits:

- Demand-revealing referenda would improve the quality of debate by forcing partisans to say how much they value indepdendence or the union. This would moderate the rhetoric on both sides and militate against some forms of self-deception - though it would of course be too optimistic to think demand-revealing referenda would eliminate all cognitive biases.

- Demand-revealing referenda reduce bitterness. In my example, Bruce and Charlie can console themselves by knowing that if they had really wanted to save the union, they should have voted more. In this sense, losers have themselves to blame, not others. This should reduce the recriminations that follow the result.

There's one objection to this scheme that I don't think is adequate - that you can't put a price upon feelings of nationhood. This fails because we already put prices onto lots of things: libel laws put a price upon reputation; the criminal injuries compensation authority prices injuries; and NICE even puts a price upon life. There shouldn't, therefore, be an objection in principle to pricing national sentiment.

Another objection is that demand-revealing referenda give power to the rich; the more money you have, the more you can afford to vote a big sum.

But it's not clear how decisive this objection is. Existing political arrangements also give the rich power, not only because they can make donations to parties and causes but also because the media defer to and publicize their opinions.

Insofar as this is a decisive objection, it is a case for reducing inequality rather than for rejecting more efficient forms of public choice.

And herein lies my point. One under-appreciated cost of inequality is that it might reduce the quality of public decision-making.

* I say "in principle" because if they were to be directly compensated, they would have an incentive to overstate their opposition to independence in the hope of getting a bigger pay-cheque. This would remove a big benefit of demand-revealing referenda, namely that they encourage people to state their true preferences.

September 10, 2014

Uses of illiteracy

The level of financial literacy in the UK, says Atul Shah, is "shockingly low". I wonder to what extent this can, for practical purposes, be corrected.

What I mean is that there's a big difference between knowing something and acting on it. We all know that if you consume more calories than you burn up, you'll get fatter. But this doesn't prevent obesity. In the same way, mere brain-knowledge about financial literacy might not prevent people making bad financial decisions. There are (at least) four reasons for this:

- Desperation. Even if you know that an APR of 4000% is a lousy deal, you might also know that your kids need new shoes. Guess which fact wins.

- The media. If the business and finance sections of the papers were literate and honest, they'd say: "we don't know much about the future, so stick some of your money into equity tracker funds and get on with your life." They don't say this because they must sell adverts and wrap some text around those adverts - and high-cost actively-managed funds are more likely to advertise than trackers. More generally, TV adverts - and even the programmes themselves - encourage us to spend more and get into debt.

- Other pressures.When we feel low, we're apt to spend and borrow more. And we're also prone to spend more if our neighbours do so.

- Cognitive biases. Even financially literate investors over-invest in expensive but poor-performing actively managed funds because of overconfidence or because an anchoring effect causes them to underestimate how horribly fees compound over time.

For these reasons, financial literacy itself is not enough. What matters is not just financial planning but character planning. Just as we keep our weight down by getting into habits of exercise and healthy eating, so we stay financially healthy by having the habit of spending less than we earn.

Which brings me to a problem. This would not be in the interests of capital.

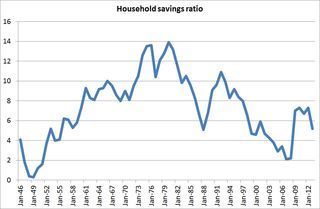

The simple maths of profits tells us this. Companies - in aggregate - can cope with high wages if those wages are returned to them in the form of consumer spending. If, however, wages are saved they become a net cost and, ceteris paribus, a threat to profits. It's no accident that the crisis of profitability in the 1970s coincided with a high personal savings ratio.

So, not only is financial literacy difficult to operationalize, it is also bad for capitalism not just because it deprives some firms of mug punters, but because it is a systemic danger to profits.

September 9, 2014

Preferences vs interests

Matthew Parris's piece in the Times has become notorious. However, he is raising an important point about political psychology which demands more attention than it gets.

He says:

I am not arguing that we should be careless of the needs of struggling people and places such as Clacton. But I am arguing - if I am honest - that we should be careless of their opinions.

This poses the old question: should politicians serve people's preferences or interests?

Parris is following a long bipartisan tradition which answers: the latter. This is what Edmund Burke meant when he said that MPs should ignore the "hasty opinion" of their constituents, and it's what various leftists have had in mind when they've worried about false consciousness.

The distinction matters because research (pdf) in behavioural economics shows that people's preferences often don't promote their interests. To take a few examples:

- Projection bias (pdf) means that we fail to foresee our future tastes. We fail to see that we'll adapt to some things (such as new consumer goods or to stock market losses) but not to others, such as commuting.

- Hyperbolic discounting means that we might never get round to things that are good for us, such as starting a pension plan or going on a diet.

- Adaptive preferences cause the poor and unjustly treated to reconcile themselves to their situation and so not demand their full entitlements.

- Anchoring effects and just world illusion cause people to accept inequalities.

- Low subjective well-being can cause people to make systematic errors such as borrowing and spending too much.

- People often violate the most basic requirements of rational preferences, such as transitivity.

Given this evidence, Parris's position seems quite reasonable. I've argued for it myself in the context of immigration. And many critics of Parris would surely say we should ignore the preferences of (say) climate change deniers or homophobes. And surely every decent parent knows that we can advance sometimes interests by ignoring their preferences.

So, what's the problem?

Simple. History. In practice, ignoring people's preferences has often meant ignoring and violating even their most basic interests. Benevolent despots have been much more discussed than observed.

There is, however, a solution here. It's perfectly possible to have an institutional framework which protects interests whilst ignoring some preferences. Human rights exist precisely to ensure that our basic interests are protected - not least from others irrational or vicious preferences.

However, I suspect the disquiet about Parris's article is founded in the fear that these rights aren't extensive enough to ensure that the interests of "struggling people" are sufficiently protected.

There is a solution here - welfare rights. Just as a right to liberty protects us from the mob, so a right to welfare would protect the worst off from those who would go further than Parris in being heedless of them. The answer to many political problems is - a citizens' basic income.

September 8, 2014

Two conservatisms

Reading Shuggy's doubts about whether Scotland really is left-wing and James Forsyth's account of Tory divisions, I was struck by a common theme - one which also links with Douglas Carswell's defection to Ukip.

The theme here is a longstanding division within the Conservative party, which we might call that between the optimistic and pessimistic traditions.

The pessimistic traditon - which I associate with Oakeshott (pdf) - is wary of change, seeing it as deprivation, whilst sceptical of those offering political programmes, fearing that they over-estimate the powers of government rationality and under-estimate the law of unintended consequences. The optimistic tradition, on the other hand, believes that change - often in the direction of free markets - is both feasible and desirable.

This, for example, was the division between Thatcherites and "wets". Wets thought the best they could do was accommodate themselves to social democracy and achieve managed decline for the UK. Thatcherites thought free markets would unleash an economic renaissance.

It is also the division within the Tories over Europe. Optimists think we are better off out whilst pessimists see the EU as flawed but fear the disruption of leaving and so seek to tweak its imperfections.

The division isn't always so clear. I'd characterise the Cameron government as a mix of both. Its belief in free schools and expansionary fiscal contraction are optimistic, whilst the general lack of legislative optimism betokens pessimism. I'd even suggest that Thatcher was a mix of both: her reluctance to reform the NHS, for example, reflected a scepticism about the limits of what she could achieve.

This, I think, helps explain Carswell's defection. His political programme - direct democracy and much smaller government - puts him on the optimistic end of the spectrum. Small wonder that he felt unhappy with the (often) cautious pessimism of Cameron.

And this is where Scotland comes in. Shuggy writes:

[The SNP] have not enacted one single redistributive policy in the last seven years...Some sharper nationalists have been candid enough to acknowledge attitudes to the welfare state in Scotland are an indication of our conservatism as a nation, at least as much as our supposed socialism. There's a whole bunch of people going to vote Yes because they want things to stay the same, not because they want change.

This reminds us of an important point. Scotland has not always been anti-Tory. Before the 1980s, it often voted heavily Conservative. This, I suspect, was because the Scots have long had a big tradition of gloomy melancholic scepticism which was comfortable with the pessimistic strand of Conservatism. Scotland turned anti-Tory - and nationalist - when that strand was overpowered by a Thatcherite and post-Thatcherite free market optimism.

You might wonder why I'm saying all this; why should I intrude into the private grief of Tory unionists?

Simple. I am sympathetic to the Oakeshottian pessimistic tradition, and fear that its eclipse is a costly one. The divisions within the Tory party, and the possible break-up of the UK, show that those costs are even more widespread than I'd imagined.

September 7, 2014

Interest rates & the 1%

Nick Rowe says some of the answers to Paul Krugman's question - why do some of the 1% want to raise interest rates? - are daft conspiracy theories. I'm in two minds here.

Let's start by sharpening Krugman's puzzle. Since the mid-80s, the income share of the 1% has risen at the same time as real interest rates have fallen. This tells us that low rates are compatible with the 1% doing well. And there are good reasons why this might be so. Easy money is good for asset prices, and low rates allow banks to borrow cheaply, to the benefit of senior bankers.

Hence the force of the question: why do some of the 1% want higher rates?

One big reason is an empirical claim - that a small rate rise now would nip inflation in the bud and so prevent bigger rises later. In this way, a rate rise now is consistent with low rates over the long-term. This "stitch in time" reason for a rate rise was expressed by Andrew Lilico of the shadow MPC, who favours (pdf) a rate rise as "a chosen small step to normalisation rather than the first forced step in a series of rapid rises."

In this sense, I sympathise with Nick. We don't need a conspiracy theory. Those who want higher rates are making a reasonable (though I think dubious) intellectual point.

However, there is a political undertow here. It's about the balance of risks. In particular, the 1% are more inflation-phobic and less unemployment-phobic than the rest of us.

I agree with Steve that the rich hate inflation not least because it creates uncertainty. (There's also the historical point that the inflationary 70s also saw the nadir of the fortunes of the 1%: this might be just coincidence, but why risk it?)

This alone creates a bias to tighten. What amplifies this bias is that the rich can tolerate mass unemployment. Nick's parallel with the 1930s is, I think, irrelevant. Back in the 30s, mass unemployment was a threat to the rich because workers could see a plausible alternative to the existing order in communism. Today, by contrast, there are no big feasible alternatives to capitalism and so unemployment is not a political danger - which means it is more tolerable.

This answers Peter's question: why has the Keynesian coalition vanished from modern politics? It's because it is no longer politically necessary. It was not Keynes who convinced capitalists of the need for full employment but Lenin.

That said, it's not necessarily in the interests of the rich to have really high unemployment, because this could weaken aggregate demand sufficiently to depress share prices and increase default risk. However, the extent to which this is the case depends upon whether growth is wage-led or profit-led: a low wage share might depress consumer spending and hence growth, but on the other hand, a high profit share might embolden capitalists to invest. Reasonable people can disagree on the extent to which this is the case and thus the extent to which unemployment is good for the 1%.

On balance, then, I sympathize with both sides. On the one hand, Nick's right to say the call for higher rates is the sort idea that people reasonably disagree about. But on the other hand, an understanding of economic policy surely requires us to ask: what is in the interests of the 1%?

September 4, 2014

The simplicity paradox

Simon wonders why simple theories of inflation are so attractive. For me, this raises a paradox.

There's a long tendency for people to be attracted to simple ideas. Many believe that there are easy solutions to tricky problems - be they independence, a smaller state, getting companies to pay fair taxes, whatever. (Yes, Marxism used to be among such ideas.) There's a name for this - the Casaubon delusion, the notion that there's a key to all mythologies.But, as several millions corpses in the 20th century warn us, such keys often don't exist. Foxes (pdf), who know many small things, do better than hedgehogs who know one big thing.

However, the opposite of a great truth is another great truth. In other contexts there are indeed simple solutions or near-solutions.Gerd Gigerenzer has shown (pdf) that simple rules of thumb are surprisingly effective, and evidence from many different contexts supports the claims of Robyn Dawes (pdf) and Paul Meehl (pdf), that simple models often out-perform expert judgment.

Take two examples of this.

One comes from stock-picking. There's good evidence that some strategies do beat the market on average over the long-run: momentum, defensives and quality. Such stocks can be identified not by judgment, but by simple stock screens.

Another comes from management. As Nick Bloom has shown, good management (pdf) often consists not so much in the exercise of judgment and discretion, but in the implementation of control and feedback rules; the work of Shann Turnbull is interesting in this context too. (This is not to say that implementation is necessarily a simple task).

However, there is popular resistance to the use of such simple methods. Very few stock-pickers rely solely upon simple screens* and our attitudes to management - especially among the political-media class - haven't progressed beyond "ju-ju man do magic."

So here's the paradox. We often believe in simplicity when we shouldn't, and don't believe in it when we should. John Stuart Mill said that liberty is often granted when it should be withheld and withheld when it should be granted. The same, perhaps, applies to simplicity.

* This might be reasonable for professional fund managers as such strategies carry benchmark risks, but retail investors have no such excuse.

September 3, 2014

Fighting the pro-capitalist state

Owen Jones has a brilliant description of how the state doles out welfare to the rich whilst bashing the poor. What should be the political response to this?

I fear that social democrats see this merely as a failing of personnel; if only we had politicians of enough courage and sense of justice, things would be different. In fact, this is nowhere near enough. There are powerful structural reasons for the pattern Owen describes - for why, in Marx's words, the state is "a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie." I'm not thinking here merely of the fact that capitalists make political donations and offer well-paid jobs to superannuated politicians and expect their money's worth from doing so. There are two other mechanisms.

One is that governments need economic growth, which makes them dependent upon capitalists. Michal Kalecki put this well:

Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence. If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment...This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.

This explains why the government gave big handouts to the banks. In 2008 bankers could credibly claim that without those handouts, the economy would have collapsed.

Broadening the point slightly, it also explains the spread of outsourcing. In a world of secular stagnation, profits can't grow much through ordinary investment and technical change, as both are weak. Instead, profits must grow by expanding the domain in which profits can emerge - hence the corporatizing of state functions.

Secondly, politicians believe that the private sector has management expertise. Outsourcing happens because ministers think that the private sector can manage some functions better than government. And the banks were left unreformed because the government thought bankers' expertise was necessary to restore the banks to profitability.

A reversal of the trends which Owen decries requires a weakening of these two mechanisms. Is this possible?

I suspect the second mechanism is the more vulnerable one. The left can and should devote far more effort to attacking the myth that private sector managers have expertise. This would consist of:

- Pointing out that the claim to such expertise is very often merely an ideological front for theft.

- Emphasising the distinction between markets and capitalism. Insofar as the private sector does increase efficiency, it is to a large extent because market forces drive out (pdf) inefficient producers, and not because good management raises the performance of existing ones.The fact that outsourcing firms are often incompetent fraudsters shows how hard it is to raise efficiency in honest ways.

- Granted, there is sometimes such a thing as good management. But it consists (pdf) in ensuring good control and feedback structures are in place. It does not mean mindless wibble about leadership, strategy and vision.

- Where some people have the skill to build such structures, their expertise should be under democratic control. The expertise of scientists and economists is subordinate to the political process. The expertise of managers should be no different.

Saying all this, though, merely runs into a problem. The state is actually shifting in the exactly opposite direction. It is embracing a top-down cult of management which is the enemy of creativity and professionalism.

Marx thought that the pro-capitalist state could only wither away after a socialist revolution. I fear he was right - and that such a revolution is a distant prospect.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers