Chris Dillow's Blog, page 113

October 17, 2014

Diversity trumps ability

Jon Lansman wants Labour MPs to be "ordinary people who have held normal jobs" rather than career politicians. There's a powerful piece of thinking on his side - the diversity trumps ability theorem. This is an extension of James Surowiecki's wisdom of crowds theory, but it has been mathematically formalized by Lu Hong and Scott Page, who summarise it thus:

When selecting a problem-solving team from a diverse population of intelligent agents, a team of randomly selected agents outperforms a team comprised of the best-performing agents.

I'll spare you the maths, but give you the gist. Let's suppose that we want to find the best possible policy, according to some objective criteria - that is, we are in the domain of epistemic (pdf) democracy (pdf). Suppose too that there is bounded rationality and limited knowledge and that each individual selects the best option using his own information set and decision rule.

In these conditions, each individual, if s/he is moderately competent, will find a local maxmimum - the best option, given his/her information and decision rule.

But local maxima aren't necessarily global maxima. And Hong and Page show that even experts might well not find that global maximum because their decision rules and information sets might not be wide enough to encompass the best option: this might be because of deformation professionnelle, or groupthink or simply because their Bayesian priors limit the number of options they search for.

Instead, widening the population of searchers increases our chances of finding that global maximum, because doing so brings more decision rules and information sets to bear on the problem. Cognitive diversity - in the sense of different ways of thinking - can therefore beat experts. It increases our chances of finding the best option. This might be why diversity within companies is associated with more innovation.

Note that this requires effective deliberative democracy, so that lesser options can be discarded in favour of better ones; simple "speak your branes" direct democracy is not sufficient.

Jon's call for an end to Labour's meritocratic preference for career politicians should be seen as an endosement of the diversity trumps ability theorem.

Now, I'm not saying this theorem is universally valid. The virtue of fomalizing it as Hong and Page have done is that it allows us to see more clearly when it is and when it isn't, and John Weymark shows that there are conditions in which it doesn't hold. My hunch, though, is that it might be sufficiently applicable to the Labour party to endorse Jon's call.

Herein, though, lies what some might see as a paradox. The diversity trumps ability theorem is the strongest part of the case for free markets. It is by increasing the diversity of firms that we increase our chances of finding good new products and more efficient processes. The fact that so much (pdf) productivity growth comes from entry and exit rather than from the growth of existing firms can be seen as corroroboration of our theorem.

In this sense, the case for free markets and the case against decision-making by tiny homogenous elites have a common root.

October 16, 2014

Why Freud's wrong

As Lord Freud's more illustrious ancestor pointed out, our unguarded comments can sometimes reveal our true sentiments. It's for this reason that his claim that some disabled people are "not worth the full [minimum] wage" has outraged so many.

At best, the statement is careless. Sam is entirely correct to say that there is a huge distinction between people's moral worth and the value of their labour; the existence of bankers suffices to prove this.

There are, though, two issues here.

First, some of our language and hence thought blurs what should be a considerable distinction. When we speak of wages as "earnings" we are importing a notion of moral worth into what is in fact an amoral exchange. Similarly the common but cringeworthy talk of a man being "worth" £x million equates wealth with moral standing. As Adam Smith said in his better book, we have a "disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition." (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.28).

Secondly let's give Freud the benefit of the doubt, and assume that he meant that the labour of some disabled people is worth less than the minimum wage. (Giving him this benefit might be an example of what Smith meant, but let that pass.) Is he right? Should we relax the minimum wage to price them into work?

Such a view makes some sense if you think in terms of simple marginal productivity; there are some severely disabled people who can't do much. In the real world, however, the applicablity of marginal product theory is, ahem, dubious. As Lars Syll says (pdf):

Wealth and income distribution, both individual and functional, in a market society is to an overwhelmingly high degree influenced by institutionalized political and economic norms and power relations, things that have relatively little to do with marginal productivity in complete and profit-maximizing competitive market models – not to mention how extremely difficult, if not outright impossible it is to empirically disentangle and measure different individuals’ contributions in the typical team work production that characterize modern societies...Remunerations, a fortiori, do not necessarily correspond to any marginal product of different factors of production.

The key phrase there is "power relations." Years ago, I had a summer job cleaning in a bakery. Two of my colleagues were what were euphemistically called "a bit simple." But they were actually good workers - not least because, unlike we students, they didn't think hard graft was beneath them. If Freud had his way, people like them would be badly paid not because they can't work, but because they lack the bargaining power to demand their economic worth. In this sense, the call to scrap minimum wage laws is - in practice - a green light for the exploitation of the most vulnerable. Better ways of helping the disabled would be ways of improving their bargaining power: stronger trades unions, full employment, a citizens' basic income.

It is for this reason - rather than any mis-speaking - that Freud should be condemned. Either he is too stupid to see that labour markets are saturated with inequalities of power, or he doesn't care. Whichever it is, his position as a minister merely vindicates Adam Smith:

In the drawing-rooms of the great, where success and preferment depend, not upon the esteem of intelligent and well-informed equals, but upon the fanciful and foolish favour of ignorant, presumptuous, and proud superiors; flattery and falsehood too often prevail over merit and abilities.

October 15, 2014

Leaders' constraints

Nick Cohen has prayed me in aid of his call for Labour to sack Ed Miliband, by arguing that the Labour party is like a failing company, drifting towards failure.

I like the analogy between Labour and the firm, but I'd draw the opposite inference from Nick - that it suggests that changing leader would have little effect.

The analogy works because Labour, like companies has vintage organizational capital. It has a history and corporate culture which governs its behaviour today: it must be a centre-left party just as Marks & Spencer must sell knickers.

But here's the problem. This capital is both a strength and also a source of constraint. Corporate bosses' room for manoeuvre is constrained by groupthink, inside vested interests, corporate technology, bounded knowledge and - of course - market forces. Such constraints imply that leaders often make little difference. Paul Ormerod and Bridget Rosewell have shown (pdf) that corporate extinction is largely unpredictable and Alex Coad has shown that growth is mostly random. These two facts imply that corporate leaders have much less control over their fate than everyone pretends.

Much the same is true of the Labour party. Any leader would face tight constraints, for example:

- Policy options are seriously limited: there are few policies which would satisfy the three criteria of boosting economic growth, increasing equality and being popular.

- Labour is operating in a market for votes where customers are woefully ill-informed and irrational, not least about inequality.

- Any leader would be undermined by the media. If Balls were leader, he'd be presented as a Brownite thug; David Miliband would be an out-of-touch wonk; Andy Burnham too laddish and lacking gravitas. And so on*.

- Labour has ceased to be a mass party, and so is dependent for cash upon either unions or a few rich benefactors.

- The power of the rich, along with the fact that it's just darned difficult for policy-makers to affect long-run growth, greatly limits what Labour could do or say.

Such forces mean that pretty much any Labour leader would look inadequate. This is all the more so because part of Labour's corporate culture is a questionable record in actually picking leaders.

I say all this not so much to agree with Rob that a change of leader is undesireable, but also to raise a question: could it be that we pay too much attention to individuals in politics, and under-rate the many constraints they face?

* Even Jesus Christ wouldn't be a "credible" leader. Imagine if Nick Robinson had been at the Sermon on the Mount. "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth" - "It's a core vote strategy and an uncosted promise. The question remains: can Mr Christ engage with middle England?"

October 14, 2014

Job polarization

The Times' headline writers have given us a nice example of journalists' habit of equating the economy and the deficit. They've titled a piece by Ed Conway on how low wage growth has depressed tax revenues: "The UK is paying the price of its job miracle" - as if the UK is the same as the government.

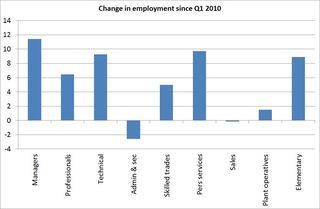

But what, exactly, is the problem here? My charts, taken from the ONS, might shed some light.

The first shows employment growth by occupation since Q1 2010 - which is when employment troughed; the figures refer to full-time employees and so exclude part-timers and the self-employed.

This shows that there has been strong growth in jobs in two low-wage occupations: personal services and elementary occupations. But it is wrong to say that there's been a general shift to low-paid work. Sales workers and plan operatives have little jobs growth - and indeed contraction in the former case. And highly-paid management jobs have grown faster than other occupations.

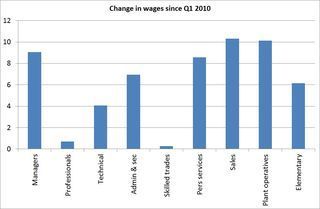

My second chart shows nominal wage growth. This has been relatively strong - I stress relatively - for lower-wage occupations. However, managers have also seen relatively high wage growth.

All of this isn't obviously consistent with the idea that falling real wages mean that workers have priced themselves into jobs*. If this were the case, you'd expect to see the biggest rises in employment in those occupations where relative wages have fallen. Instead, some sectors which have seen big employment rises have also seen rises in relative wages: this has been true for personal services and management.

These data are more consistent with job polarization than with a general shift to less skilled work or workers pricing themselves into jobs. There's been increased demand for managers and personal services workers - hence the combination of rising jobs and relative wages - but declining demand for routine white collar administrative jobs. (Quite why demand for managers seems to have risen is another story.)

I don't say this to reject the idea that employment growth has been unfavourable for the Exchequer; I suspect the problem has been decorporatization - a shift to self-employment - more than shifts within the composition of employment.

* I'm not saying the hypothesis is wrong - just that it doesn't jump out of these data.

October 13, 2014

Out of touch?

Yesterday, Ryan Bourne tweeted:

Just 13 per cent of people think 'Inequality' is the biggest issue facing country. Yet left wing commentators call others out of touch!

There is, I think, an answer to this. We must distinguish two ways of being out of touch with people. One is by not sharing their views, the other by not heeding their interests. I'll own up to being out of touch with voters' views, but I'm not sure I am so out of touch with their interests.

This distinction is, of course, only possible if people's preferences don't serve their interests. And in the case of inequality, I think one can argue this.

It is at least possible that inequality has adverse effects not just for the quality of democracy, trust (pdf) and social cohesion (pdf) but economic efficiency (pdf) too. This isn't merely because a shift in incomes to the rich, who happen to save more, depresses aggregate demand. It's also because inequality increases the narcissistic self-confidence of the rich and encourages short-termism, both of which contribute to financial crises.

However, there are psychological mechanisms (pdf) which cause people to accept inequality: these include the just world effect, status quo bias, anchoring heuristic and resignation.

The natural inference of these two thoughts is that inequality matters more than voters believe. We lefties might be out of touch with voters' beliefs - but we care about inequality precisely because we believe it damages voters' interests. And one can argue, as Daniel Hausman does, that it is interests that matter more than preferences.

In saying this, I'm not taking a uniquely leftist position. I'm echoing Edmund Burke, who argued that MPs should ignore the "hasty opinion" of voters if this clashed with the national interest. And I suspect even Ryan would agree. Most people want energy companies to be nationalized. Ryan probably thinks otherwise. This isn't because he's out of touch but because he thinks such a preference would not in fact have the benefits voters believe it would.

My point here is not about inequality: exactly the same thinking applies to immigration too. Instead, it's about the nature of politics. When we lefties (or, more precisely, I) complain that politicians are out of touch, what we mean is that professional career politicians serve the interests of the rich rather than the public. Our fear is that, when Ed Miliband promises to "listen" to voters, he will put Labour in touch not with voters' true interests but rather with their basest and most irrational impulses.

October 12, 2014

Cargo cult thinking about virtue

Tristram Hunt, inspired perhaps by ResPublica's call for a bankers' oath, wants teachers to take a public oath committing them to professional standards. This contains a speck of sense, but ignores some big questions.

The speck of sense is people have an urge to behave consistently. Once we have made a commitment we thus feel obliged to stick to it. As Robert Cialdini says:

Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. (Influence, p57)

So far, so good. There is, though, a lot that this misses. Not least is that the problem with teachers isn't so much that they behave unprofessionally in the classroom but that they don't stay in the classroom at all; two-fifths of newly-qualified teachers leave the profession within five years.

What's more, this ignores the fact that, insofar as a lack of teacherly virtue is a problem, the cause lies not (just) with inadequate individual teachers but in societal and institutional pressures which undermine professional ideals. I'm thinking here of three things:

- Managerialism. Setting targets and encouraging teaching to the test are not always compatible with the virtue of teaching, which is to bring the best out of every student. This is also a big reason why so many teachers leave. The problem here is - of course - not confined to teaching. In all professions, there's a tension between hierarchy and professionalism; one seeks to reduce professional autonomy, the other to expand it; one is concerned with the goods of effectiveness, the other with the virtues of excellence.

- Anti-intellectualism. A society in which young people want easy fame, in which schools are regarded as ideological state apparatuses, in which the mass media is trashy, in which intelligent people have no place in politics, and in which even supposedly valued science graduates are modestly paid is not one in which education has a high priority. Teachers are therefore running into strong headwinds.

- Money. Spending per pupil in secondary schools is just £5671 per year - one-third that of the better independent schools. Even if we leave aside the fact that you get roughly what you pay for, what does this difference tell us about how society values the education of the 93% of pupils who are educated in the state sector?

My point here is not merely a narrow one about teaching. It's a wider one about an important and neglected question: how do we promote virtue when there are pressures which undermine it? I fear that in not addressing this question properly, and in assuming that the fault lies solely in individuals and in neglecting those countervailing pressures, Mr Hunt is merely engaging in cargo cult thinking; he's fetishizing the rituals of virtue without investigatng the causes of it. It's enough to make me suspect that the Labour party might not be serious about social change.

October 11, 2014

The reification fallacy

Yesterday I asked whether those people who feel uncomfortable hearing foreign languages on the bus will also feel uncomfortable watching Ola Jordan and Kristina Rihanoff tonight. My question was a serious one. What I was hinting at is that concern about immigration is often not directed at specific people. When people say they dislike immigration they are not - except for a handful of outright racists - thinking of Ola Jordan, or Mo Farah, or the guy who owns the corner shop or the girl who works in the chippie or their work colleagues, but rather some amorphous mass over there that they read about in the papers.

It is this that explains a paradox - that worries about immigration are greatest where actual immigration is lowest: Ukip has big support in Clacton and (I regret) Rutland rather than London or Leicester. One poll (pdf) for Mori found that whilst 76% of people think immigration is a very or fairly big problem for Britain, only 18% think it is in their own area. As Mori says:

Readers of the print media were more worried about immigration than nonreaders, as were particular readers of titles that have had a heavy negative focus on this issue.

What's going on here is, perhaps, the reification fallacy - when an abstraction is treated as if it were a concrete, real thing with real effects.

I emphasize "perhaps", because one might reasonably be disquieted about immigration not because of its observable effects - which are benign in the economic sphere - but because it might in future have adverse effects upon social cohesion. But this surely doesn't warrant the high profile immigration has: why worry about potential problems rather that actual ones?

This, I suspect, is not the only example of the reification fallacy. If you were to ask those who want to leave the EU "what is the EU stopping you doing now?" I fear you'd often be met with silence or error. And, I suspect, managerialism contains an element of the fallacy; it attributes real effects to what is sometimes a mythical quality of"leadership"*.

Now, I am not saying here that visual evidence is all we need. When Marx said that "all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided" he was making the important and non-partisan point that social processes are often hidden from us. But there is a big distinction between uncovering things that exist and worrying about things that don't.

Even so, this raises the question: what would politics be like if people only relied upon the evidence of their own eyes? I suspect that economic issues of low wages and unemployment would be much more important.

However, it doesn't necessarily follow that there'd be a big shift to the left. Even in the days before the mass media workers were often quiet or conservative even though they had good reason for grievance - as Robert Tressell famously described. And this warns us that reactionary impulses shouldn't be blamed solely upon the media.

* I'm not saying this fallacy is confined to the right. When rightists ask: "what harm is inequality doing given that the rich are invisible?" they are accusing the left of the same fallacy. Personally, I think their question can be answered satisfactorily, but it's possible that some leftists are committing the fallacy.

October 10, 2014

The Ukip question

Ukip's success in yesterday's by-elections poses a question for the left: why has disquiet with the Establishment led to support for a rightist party rather than the left?

It would be wrong to dismiss Ukip voters as merely racist. For one thing, their massive support for public ownership of utilities puts them to the left of Labour. And for another, as Matthew Goodwin has pointed out, they are reacting against being neglected by the main parties; on this, even Richard and Frances agree.

On both grounds, the Left could mobilize such voters. But it hasn't. Why?

You might reply that it's normal for meanspiritedness and racism to increase in hard times and Ukip are tapping into this. But this just relocates the question: why have we failed to prevent such atavistic instincts gaining political expression? The question gains force because there's a strong rational argument against anti-immigrationism:

- The evidence (pdf) shows that immigration actually increases jobs and wages - perhaps even of the worst off.

- There are many bigger threats to the living standards of the sort of less educated people attracted to Ukip such as power-biased technical change, deindustrialization, globalization (pdf) and secular stagnation. A politics that was seriously concerned for the worst off would address these issues, rather than treat migrants as a threat.

- Even if we were to concede that immigrants are a threat to some British workers, the solution is not immigration controls - because if foreign workers stayed at home they'd depress UK wages through trade. Instead, the answer is some mix of jobs guarantee, expansionary macro policy, stronger trades unions and a citizens' basic income.

So, why have these arguments so little force with voters? Is it because the Left hasn't been brave enough to make them? Or because they are wrong? Or because the Left lacks a decent platform to do so and is shouted out by the media?

You might reply that I'm missing the point, and that disquiet with immigration is because people feel "uncomfortable" traveling on a bus or a train where nobody speaks English. This, though, poses other questions: if this is so, why do relatively few people say immigration is a problem in their own area (p90 of this pdf), and how come Ukip did so well in Clacton, which has so few immigrants? Do such people also feel uncomfortable watching Ola Jordan and Kristina Rihanoff on Strictly Come Dancing? And why has a non-economic feeling become so strong at a time of hardship?

Now, it certainly suits the Establishment for generalized discontent to be channelled into support for an anti-immigration party. It's no accident, therefore, that the media has emphasized anti-immigrationism and bigged up Ukip. But again, there's a question: why has the Left been so impotent in the face of this?

It's tempting to blame the power of the Establishment and the supineness of the Labour party. But are these really solely to blame? Or could it be instead that part of the fault lies also with the non-Labour Left itself, which is so congenitally disorganized that it couldn't pour piss out of a boot if the instructions were printed on ther heel?

October 9, 2014

The Establishment: a review

On the cover of The Establishment, Russell Brand describes Owen Jones as "our generation's Orwell." The comparison isn't wholly fanciful. Unlike almost everyone else on the left (including me), Owen writes beautifully well. Orwell said that good prose should be like a pane of glass, and Owen has given us a very clear window onto the nexus of business, politicians and the media that has greatly strengthened the wealth and power of the 1% since the 1970s.

Moreover, the very fact that he has chosen to attack the Establishment, at a time when more journalists turn their fire upon the poor, makes Owen - like Orwell - a heroic maverick.

It would be curmudgeonly to pick fault with what is in many ways a superb assault upon such an important target. But I am a curmudgeon, so here goes. One of my gripes is that I don't think he quite follows through on his early observation:

The Establishment is a system and a set of mentalities that cannot be reduced to a politician here or a media magnate there...Personal decency can happily coexist with the most inimical of systems.

This is deeply true. However, whilst Owen is great at describing "socialism for the rich" and the revolving doors that link politicians, journalists and the media, I fear he underplays the extent to which the power of the Establishment is systemic. For example, the problem with the media isn't that just that its owned by right-wing bastards or that journalists are drawn from rich backgrounds and are close to politicians. It is instead that the media have systematically created a hyperreal economy from which the interests of working people are largely excluded. And the BBC is perhaps as guilty of this as the Murdoch press.

Similarly, companies have power over government not just because of lobbying but because they control business "confidence" and therefore the fate of the economy.

These are not the only structural forces Owen underplays. He doesn't say that corporate welfare is needed because of the weakness of capitalism; a falling profit rate and dearth of monetizable investment opportunities means that capitalism cannot stand on its own two feet.

Indeed, I fear that Owen might be too optimistic about what even reformed capitalism can achieve. In an otherwise mostly reasonable list of policy suggestions (other than the call for capital controls), he claims that an active industrial policy could create "a new wave of green industries". But can it really?

My second gripe is that I fear Owen is missing a trick in not sufficiently emhpasizing the sheer incompetence of the Establishment in its own terms; it was, remember, bad management that brought down the banks. Bosses' claim that they deserve huge salaries because of their managerial talent is mostly plain wrong.

This matters. Owen says the left should buid "a compelling intellectual case that can resonate with people's experience". Surely a challenge to managerialism must be part of this. If there's one thing that's true and resonant with people's day-to-day experience, it's that bosses aren't as smart as they think.

So much for gripes. Owen also raises three questions which I'm not sure he (or I!) have an answer to.

First, how much power do the media have? Owen invites us to believe: a lot. But he also notes that threre's huge support for public ownership, suggesting the media's control isn't that great. So which is it?

Secondly, what's the link between ideas and systems? Owen devotes a chapter to right-wing think tanks - what he calls "outriders" for the Establishment. But it is odd to credit them with much influence these days, given that - as he rightly says - the idea that we have a free market is a "con" and a "fantasy." As Owen notes, the more intelligent and sincere right-libertarian is disquieted by our crony capitalism. Does this mean the think tanks were useful idiots for the rich? Or that their project failed eventually?

Thirdly, how do we achieve meaningful social change? It took free market think tanks decades to acquire influence: the Mont Pelerin Society was formed in 1947, 40 years before the UK began privatization. This suggests that social change is a long game. Could it be that a shift away from crony capitalism will be achieved not merely by formal political agitating but also by what Erik Olin Wright calls interstitial tranformations (pdf) - small but cumulative moves in the direction of decorporatization and decommodification?

October 8, 2014

Free markets need socialism

Aditya Chakrabortty describes well the huge size of the corporate welfare state. What he leaves out, however, are the colossal economic and political forces that give us such crony capitalism.

Of course, there's nothing new about state support for business: remember the East India Company? But it could be that there is especial need for it now. In a time of slower technical progress (pdf) and a dearth of monetizable investment opportunities, capitalism cannot generate sufficient profits under its own steam. Instead, it needs the state to create them by outsourcing, privatizations, bailouts and tax credits wage subsidies.

What's more, there are huge pressures on politicians to give business what it wants:

- As Kalecki pointed out, in a capitalist economy, growth and jobs depend upon business confidence, which governments must maintain.

- Politicians want money; bosses want political power. And when one person wants what another has, guess what - there'll be a trade.

- Politicians believe that the private sector has managerial skill. It thus outsources functions on the grounds of "efficiency". However, such skill might be partly illusory. Belief in it might instead be just the latter day manifestation of what Adam Smith called the "disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition*."

This poses a question. Given these structural tendencies for capitalism to degenerate into cronyism, could it be that some form of market socialism (big pdf) would do better? For example:

- It would eliminate the need for wage subsidies partly because a decent citizens basic income would allow workers to reject exploitative jobs, and partly because wages would be topped up by a share of profits.

- The maintenance of full employment via jobs guarantees and sane macroeconomic policy would reduce capitalists' ability to demand handouts and tax breaks, because "confidence" would no longer matter quite so much.

- Greater pre-tax egalitarianism - as workers' control enables them to restrain bosses pay - would reduce politicians' tendency to defer to the rich. And it would also reduce their incentive to give companies favours in exchange for high-paying jobs when they leave office.

Now, I say this tentatively as I'm deliberately vague about the precise nature of market socialism, vaguer still about how to achieve it, and because I'm not at all sure it would eliminate all the many pressures towards cronyism. I'm merely raising a question: could it be that, if you are serious about wanting a genuinely free market economy, then you must advocate not capitalism but socialism?

* Theory of Moral Sentiments I.III.28

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers