Chris Dillow's Blog, page 114

October 7, 2014

"The economy"

On the Today programme yesterday, Nick Clegg said (2'11 in):

You've got a Labour party that of course famously refuses to talk about the economy, a leader that failed to even address ther deficit.

Hold on. Labour has been banging on for months about the cost of living crisis. Sure, Miliband "forgot" to talk about the deficit in his conference speech. but the deficit is - of course - not the economy.

Then on PM yesterday (about 17'402 in), Carolyn Quinn said:

The Lib Dems claim they'd fix the economy more fairly than the Tories; they'd eliminate the deficit not just by cutting spending as the Tories promise but by raising taxes on the rich.

In the context she's using the word, she clearly means not "fix the economy" but "fix the deficit".

Now, I had thought that Clegg had merely mis-spoke. But it's unlikely that two people would mis-speak in exactly the same way within hours of each other. I suspect something else is going on - the construction of a hyperreality.

They are trying to equate the deficit with the economy, to give the impression that good economic policy consists not in boosting real wages, cutting unemployment, or addressing the threat of secular stagnation but merely in "fixing the deficit." The fact that Clegg is a politician and Quinn a journalist is, in this context, a distinction without a difference; they are both in the same Bubble pushing the same quack mediamacro.

Worse still, by "fixing the deficit" they mean some type of austerity. But there's a big difference between the two. We could - perhaps - fix the deficit by state-contingent fiscal rules, or by adopting a higher inflation target (or NGDP target) and thus using monetary stimulus to inflate our way out of government debt. However, even these options are outside the Overton window.

Instead, the only economic policy permitted by the Bubble is the fake machismo of "tough choices." Not only are these tough only for other people - mostly the most vulnerable - but they don't even work in their own terms; one lesson we've learned since 2010 is that "tough decisions" to cut the deficit don't actually do so as much as their perpetrators hope. But then, in the Bubble's hyperreality, neither justice nor evidence count for anything.

October 6, 2014

Tory crisis, capitalist crisis

Much has been written about the divisions in the Tory party and the realignment of the right. I'd be failing in my Marxian duties if I didn't link the Tories' troubles to the crisis of capitalism. So here goes.

For years, there have been - roughly speaking - two strands of Conservatism, which can coexist in the same person: a sceptical, melancholy strand which aims at managing decline; and a more programmatic one.

The latter - associated with Thatcherism, the Britannia Unchained crew and Tory defectors to Ukip - goes like this: if only we can shrink the state, cut red tape, get out of the EU and restrict workers' rights, we'll unleash the dynamism of British entrepreneurs and enjoy strong growth.

However, whilst this might have worked in the 80s, it's questionable whether it'll work now. If the secular stagnationists are right, capitalism has lost its mojo, and there's no underlying dynamism just waiting to be unlocked. And if wage-led growth theory is right, bashing workers might merely depress aggregate demand.

Herein, perhaps, lies a reason for the growth of crony capitalism, about which some Tories are sincerely uncomfortable; in secular stagnation with a dearth of monetizable investment opportunities, capitalism doesn't have the oomph to grow under its own steam, so it needs the state to create and guarantee sources of profits.

We can see the two strands of Conservatism as mirroring the question about whether secular stagnation exists. Programmatic Tories deny the problem and think that another dose of Thatcherism is sufficient, whilst the sceptical-melancholy tendency fears that we might be in a stagnant world so that free market policies won't work now even if they worked before.

Now, I'm not saying that the Tories are having the debate about secular stagnation and wage-led growth explicitly - merely that there's a close analogy between the debate on the right and the debate among economists about the underlying vitality of capitalism. Some Tories have always been good at understanding things tacitly and intuitively.

The question: should we massively shrink the state and leave the EU, or should we merely try to shore up crony capitalism? is rooted in a question about the very nature of capitalism. With the latter in doubt, conflict within the Tory party is to be expected.

October 5, 2014

Narcissism, hubris and "success"

I've seen two things recently suggesting that the rich and powerful are prone to what might be called psychological disorders. In The Establishment, Owen Jones says that top pay and MPs big expenses claims were driven by a narcissistic "because I'm worth it" mentality. And in the FT, Gillian Tett describes how successful managers are prone to hubris.

There's something in this. Narcissism pays both across the wage distribution - because men who spend lots of time in front of the mirror earn more - and in the boardroom: narcissistic CEOs are better paid. And way back in 1986, Richard Roll said that value-destroying takeovers were often motivated by hubris (pdf) - though he was only echoing Kenneth Boulding's warning (pdf) of 20 years earlier, that:

There is a great deal of evidence that almost all organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

But I wonder: what exactly is the link between success and narcissistic overconfidence?

On the one hand, there might well be causality from hubris and narcissism to economic success. Narcissists have the thick skins which prevent them being disheartened by setbacks. And they give off more competence cues which hirers mistake for actual competence, and so are more likely to climb up the greasy pole.

However, I suspect there are also two other mechanisms here.

One is a selection effect. Many successful people can retire or downshift in their 40s because a few years of six-figure salaries and London house price inflation should allow one to build up a decent nest-egg: even with with interest rates at their present nugatory level, the price of a decent flat in Hampstead would give you an income of twice the median wage. This means that only narcissists and people daft enough to be "passionate" about their career stay in work long enough to become top managers.

Secondly, Gillian is right - success causes hubris. The thing here is that this can be true even if that success is due just to luck. A new paper by Christoph Merkle and colleagues shows that even neutral observers are fooled by randomness and so see skill where there is in fact only luck. Given the self-serving bias, it's even more likely that managers will see their own success as due to skill rather than luck. Though this is well-documented in finance, I suspect it also happens in non-financial businesses as high profits here can sometimes be due to the good luck of tail risk not materializing.

I say all this for two reasons. First, to point out a paradox. On the one hand, people with some mental illnesses - depression, schizophrenia - suffer stigma and discrimination in the labour market. And yet on the other hand, the market actually favours and produces some other mental disorders. This might be consistent with a Szaszian view of mental illness.

Secondly, all this brings into question the efficiency of hierarchies: is it really a good idea to put power into the hands of people who are systematically irrational? Despite the fact that the collapse of the banking system in 2008 gave us a clear answer to this question, hierarchy persists. Which only confirms the success of the Establishment in creating a hyperreal economy in which evidence doesn't matter.

October 3, 2014

Why not wage-led growth?

Britain's big supermarkets are in trouble. Tesco's share price has halved in the last year, Morrisons has begun a price war with Aldi and Lidl, and Sainsbury's CEO Mike Coupe says: "The supermarket industry has changed more rapidly in the last three to six months than any time in my thirty years in the industry."

There's an obvious cause of these troubles. Six years of falling real wages - with maybe more to come - have forced shoppers to become more bargain-conscious and to shift to low-cost stores. This shift is quite consistent with Mr Coupe's claims that things are changing rapidly now, because consumer spending is a matter of habit, peer effects and social norms (such as the erstwhile stigma against Lidl), and these can change slowly at first but them quickly.

This, though, implies that the wage squeeze isn't just bad for workers but also for at least part of capitalism. Which in turn supports the idea that wage-led growth (pdf) would benefit not just workers but bosses too. Perhaps, therefore, the interests of capital and labour coincide. All would benefit from higher wages.

Which brings me to a puzzle. Very few commentators on the supermarkets' woes are drawing the inference that the TUC might be right: Britain needs a pay rise because falling wages hit businesses as well as households.

Why are they not doing this? It could be, of course, that it's mistaken. Just because some capitalists would benefit from higher wages it does not follow that all would. However, whilst there has been a debate about wage-led growth in economics blogs, this debate, AFAIK, has barely entered media or business circles.

I fear there's a reason for this, pointed out by Selina Todd in The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class. Workers' interests, she says, have always been regarded by those in power as a sectional interest opposed to the national interest. Even the 1964-70 Labour government, she writes, "regarded workers' rights as being distinct from the 'rights of the community'."

From this perspective, the failure of "business leaders" to even consider the possibility that wage-led growth is in most people's interests might be an example of a path-dependent belief - an idea that lingers on even if it has outlived its usefulness.

Or is it? Perhaps instead what we are seeing here is what Kalecki called the "class instinct" of capitalists. This tells them that even if higher wages do benefit capitalists in the short-term, they are to be resisted because of their longer-term dangers. After all, if we start empowering workers, where will it lead?

October 2, 2014

Are cuts "feasible"?

On the Today programme this morning, Ryan Bourne said (2'38") that spending cuts need not have "hugely detrimental effects on the public services":

Other countries spend significantly less as a proportion of GDP than the UK. It's a question of political will as opposed to economic feasibility.

I'm not so sure.

First, though, some context. Current Tory plans envisage cuts in public spending, but with health, education and overseas aid protected. This implies large cuts elsewhere. As the OBR says:

By 2018-19 the [resource departmental expenditure limits] for unprotected departments would be 5.4 per cent of GDP, little over half the level spent in 2013-14 and less than half the level spent in 2010-11...In real terms...total RDEL spending in 2018-19 would be 22 per cent down on 2010-11 and for the unprotected departments down 45 per cent. Adjusted for the ONS’s specific deflator for changes in the price of government consumption, the declines would be 9 per cent and 36 per cent respectively. (Par 6.16 of this pdf)

The IFS numbers are quite similar. So, is Ryan right that this is feasible, or is it instead "brutal" as Rick says?

Three things speak in Ryans' favour, but I'm not convinced by any of them.

1. The cuts envisaged for 2015-16 to 2018-19 are a bit less than those we've already had.

I'm not sure, simply because we should have picked the low-hanging fruit by now, and further cuts will be harder. Also, whilst one or two years of pay restraint is feasible - especially when private sector wages are squeezed - it's not obvious that many such years are possible.

2. There have been cases of big cuts in public spending without disastrous effects around the world.

However, many of those cuts came from lower interest and welfare spending rather than departmental spending. And they came at a time when the macroeconomic environment was conducive to the possibility of expansionary fiscal contraction.

3. As Vito Tanzi and Ludger Schuknecht have shown, newly industrializing countries, such as South Korea, have combined low public spending with good social indicators.

The problem here is path dependency. It might well be possible to have small effective government if you're starting from scratch. But we're not. And big government can lead to big government for at least two groups of reasons:

- Vested interests. Years of big government create a client base for big government and thus pressures to maintain it. I'm not thinking here merely (or even mainly) of public sector unions. There are also capitalist interests in favour of big government, not to mention public sector managers who have more incentive to maintain their positions than to enhance efficiency.

- Cognitive limits.The difficulties the government has had with Universal Credit and free schools shows just how hard it is to actually implement change. And whilst it is possible in theory to cut waste, the (correct) Hayekian strictures that central planners have bounded knowledge warns us that waste can't be identified from the top-down.

I say all this for two reasons. First, to note an irony: the same free market theory that calls for spending cuts also tells us - through the economics of public choice and bounded knowledge - that such cuts are hard. Secondly, to note that if cuts are to be reconciled with decent services, the solution might lie in abandoning top-down managerialist conceptions of how to run those services.

October 1, 2014

The economy as hyperreality

A lot has been written about the failures of economics, some of it worth reading. However, as far as I know, nobody has pointed out that pretty much all of us - me, Simon Wren-Lewis, the Adam Smith Institute and all - make a systematic error in thinking about economic policy.

This struck me when reading this by John Kay:

Government by announcement is now characteristic of British politics. The goal is to make statements that will receive favourable media coverage. There is little perception of any need to follow up on these announcements, or consideration of how they might interact with other similar announcements, and no concern for the effects of the uncertainty these initiatives create for people engaged in real business.

This makes the same assumption that Simon makes when he writes about "mediamacro". It assumes that there is a real thing out there called the economy which policy impinges upon and so there's a distinction between impressing the media and good policy-making.

This assumption is questionable. Perhaps we should instead think of the economy as a hyperreality.

Here's Wikipedia:

Baudrillard defined "hyperreality" as "the generation by models of a real without origin or reality", it is a representation, a sign, without an original referent. Baudrillard believes hyperreality goes further than confusing or blending the 'real' with the symbol which represents it; it involves creating a symbol or set of signifiers which actually represent something that does not actually exist like Santa Claus.

And here's the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

What passes for reality is a network of images and signs without an external referent, such that what is represented is representation itself.

These, surely, are better descriptions of "the economy" as the Westminster Bubble sees it than our old-fashioned empiricist idea of "the economy" as an external reality. "The economy" is a set of symbols which exists in its own right without reference to anything else. And good policy-making consists in appearing to manipulate those symbols in a manner satisfactory to the creators and upholders of that hyperreality. "Mediamacro" is the only macro - or at least, the only macro that matters for policy purposes.

Now, you might reply here that, eventually, "bad" policy - in the quaint empiricist sense - will eventually make itself so obvious that the hyperreality can't ignore it. I'm not sure.

For one thing, voters' perceptions of empirical reality are skewed both by fundamental ignorance and by ideology. Hyperreality can thus be sustained by an interaction of the public, politicians and the media. And as Simon says, the direction of causality of the creation of this hyperreality is unclear: do the media merely reflect voters' opinions, or create them?

And for another thing, when it comes to creating hyperreality, we are emphatically not all equal. The suffering of the unemployed, poor and disabled might be "real" to them - but if you're outside the 1% you have little hope of affecting the hyperreality that matters.

What I'm saying here is that those of us who complain about economic policy are assuming what has to be proven - that there's an external reality which matters more than the hyperreality of the media-political elite. And this is questionable. To those who boast of being in the "reality-based community" there's an obvious retort: who gives a damn about your so-called reality?

September 30, 2014

The deficit: blame foreigners

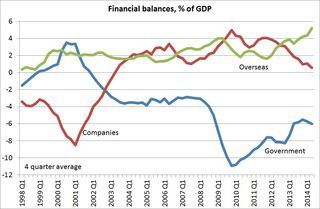

For a long time, I've argued that government borrowing is due is large part to the corporate sector's financial surplus - its excess of retained profits over capital spending. However, today's GDP figures show that something else is also happening.

These show that the corporate sector's surplus has disappeared; in fact, in Q2, companies in aggregate ran a small deficit. However, although the declining corporate surplus has been accompanied by falling government borrowing, the latter is still large. Why?

Statistically speaking, the main counterpart to government borrowing is no longer corporate net lending but rather overseas net lending - or, to put it more familiarly, a current account deficit. It is foreigners' net saving, rather than companies', that is the counterpart of government dissaving.

Of course, "counterpart" does not tell us anything about causality. So, what is the direction of causality?

You could argue that our borrowing from overseas is caused by government borrowing. Maybe government borrowing has inflated demand which in turn has sucked in imports.

Now, whilst this has happened sometimes, it is not the case here and now. Several facts tell us as much: that UK real interest rates are negative; that there are 5.65m unemployed; that inflation is low; and that real GDP has grown only 2.9 per cent in the last six years.

Perhaps, therefore, the correlation goes the other way - it is foreigners' saving that is causing UK government borrowing. Weak demand overseas means weak UK exports which means a weak economy and tax revenues.

To put it another way, in the much of the world savings exceed domestic investment. This might be because of big oil revenues (the middle east);weak welfare states and capital markets (China) or being daft twats (the euro area). Whatever the causes, such net saving means - by definition - that someone somewhere must borrow. This someone is partly the US, but also the UK government. This explanation is consistent with the fact that UK government borrowing has been accompanied by negative real interest rates.

Which brings me to a puzzle. We British tend to blame foreigners for lots of things, from unemployment to the craptacularness of the England football team.Such blame is generally wrong. And yet when foreigners might be responsible for one of our problems (assuming the deficit to be such), nobody points this out.

September 29, 2014

When failure is success

Here's a glorious example of the media's bubblethink: the Guardian's political reporters describe Osborne's stewardship of the economy as the Tories "strongest card."

Let's just remind ourselves of the facts. Back in June 2010 the OBR forecast (pdf) that real GDP would grow by a cumulative 8.2% in between 2010 and 2013. In fact, it grew by only 3.1%. Partly because of this, the deficit is much larger now than expected. In 2010, the OBR forecast that PSNB in 2014-15 would be £37bn, or 2.1% of GDP. It now expects it to be £83.9bn, or 5.5% of GDP.

This poses the question: how can such failure be regarded by the Bubble as success? Here are five possibilities:

1. The peak-end rule. Daniel Kahneman has shown (pdf) that our memory of events is distorted by how they end, so that great pain followed by discomfort is regarded more favourably than pain alone, even if the former episode goes on for longer. The fact that the economy is now growing therefore leads us to under-estimate the pain of the stagnation of 2011-12 - just as our relief at finally getting home causes us to overlook the fact that the cab-driver took us on a two-hour detour.

2. Luck. The collapse of productivity growth means that the modest growth we've seen has translated into surprisingly strong jobs growth, for which Osborne is (wrongly) getting credit. In fact, if productivity had grown at a normalish rate in recent years, unemployment would have hit a record high. I doubt if Osborne would be regarded as a success in that case.

3. Risk aversion and status quo bias. People prefer the devil they know - and Osborne's stewardship is better known than Labour's policies.

4. False excuses. The coalition has tried to blame the euro area's weakness for our weak growth. This, though, won't wash; a policy that works only if everything goes OK is no policy at all, given that surprises are inevitable.

5. Managerialist machismo. If you use the language of "tough choices" and "prudence", some people will take you at your word. As Cameron Anderson and Sebastien Brion have shown, overconfident people who give off competence cues are wrongly seen by others as having genuine competence.

Whatever the reason, the fact is that it is only within the groupthink bubble that Osborne's macroeconomic policies can possibly be regarded as a success.

September 27, 2014

On correlation neglect

In the Times, Danny Finkelstein expresses disquiet about Operation Yewtree:

"My word against some bloke after more than 20 years is good enough for you?" [Liz Kershaw] asked. The police wouldn't need other evidence to charge?

"Well" replied the officer. "If it was just one girl obviously the Crown Prosecution Serivce would probably throw it out. But if more than one girl came forward, well..."

The clearest statement I have ever seen of the dubious policy of using legally weak individual allegations to support each other.

He's touching upon a widespread cognitive error here - correlation neglect.

If lots of women were to independently make allegations against someone, those allegations might be credible - though whether credible enough to overcome the reasonable doubt hurdle is another matter. The problem comes when the allegations might be correlated. If one allegation against a public figure encourages others to make allegations, the subsequent allegations might not have as much weight as they would if they were independent. The latter allegations might be cases of misremembering or mistaken identity. If so, there's a danger of an information cascade; several allegations might be due not to independent pieces of information which support each other but to a common mistake.

Now, I've used the word "might" a lot in that paragraph. But we do have a much clearer example of the danger of correlation neglect in criminal law. In 1999 Sally Clark was convicted of murdering her two babies on the evidence of a pathologist who claimed that the chances of two babies dying of cot death as Ms Clark claimed were vanishingly small. His statement was an example of correlation neglect; it might have been true if the chance of one baby suffering cot death were independent of the chance of his brother dying. But if there are common environmental risks of cot death, then the chances are correlated, so the chances of two deaths are much higher than the pathologist claimed. Ms Clark was eventually released on appeal.

It's not just prosecutors who are prone to correlation neglect. It also happens in investing. Benjamin Enke and Florian Zimmerman show that people fail to discount correlated signals about future returns, and so over-invest in assets which look good. And Erik Eyster and Georg Weizsacker show that investors treat (pdf) correlated assets as uncorrelated and so fail to diversify risk properly.

And, of course, it also happens in politics. We fail to discount the political opinions of our friends because they are correlated: our friends tend to have similar backgrounds and outlooks on life. We are, say (pdf) Glaeser and Sunstein, "credulous Bayesians", who over-react to weak information.

Such correlation neglect contributes to the bubblethink I discussed yesterday. It also generates political polarization (pdf) and overconfidence; Enke and Zimmerman show that it can be a source of stock market bubbles because investors become overconfident about future returns. In the legal context, such overconfidence can lead to false convictions.

These, of course, can have terrible effects: after she was released, Ms Clark drank herself to death. In this sense, correlation neglect can be deadly. Whether this has any relevance to the UK's decision to go to war in Iraq is a question I shall leave to others.

September 26, 2014

Bubblethink

In the Times, Phillip Collins says:

Mr Miliband...would rather forget about the deficit and talk about something else. Alas, this is not a viable choice because reality keeps forcing its way in.

Whoa there. Who's reality? It not the reality of the markets, where real gilt yields are negative and there's a shortage of safe assets. It's not the reality of an economy where the deficit is largely due to still-high unemployment and weak incomes growth. It's not the reality of an economy that's "crying out for public stimulus". And it's not the reality where our most fundamental problem is not the deficit but stagnant productivity.

What we have here is yet another example of what Simon calls mediamacro. I suspect, though, that this is the symptom of an underlying disease - that the media exists entirely within a Westminster bubble. Mr Collins thinks the deficit is a "real" problem not because there's empirical or theoretical evidence that it is, but simply because the groupthink of Very Serious People says so.

This is not the only example of Bubblethink. Another habit of the Bubble is to overestimate the number of well-paid people like themselves. This gave us the utterly cretinous headline in yesterday's Times: "Middle class? You'll be ruined by a mansion tax."

Such Bubblethink feeds on itself. One way in which it does so is by current affairs programmes relying upon a circle-jerk of gobshites to the exclusion of experts who might prick the bubble; the fact that James Delingtwat appears on the BBC more than Simon Wren-Lewis tells you all you need to know.

Another way in which it does so is through the BBC's fictitious pursuit of "due impartiality", which promotes the belief that impartiality between two parties with imbecilic ideas about the deficit or economic effects of immigration somehow represents the truth. This was brilliantly lampooned by Alexander Cockburn:

Hunter-Gault: A few critics of slavery argue that it should be abolished outright. One of them is Mr.Wilberforce. Mr. Wilberforce, why abolish slavery?

Wilberforce: It is immoral for one man ...

Macneil: Mr. Wilberforce, we’re running out of time, I’m afraid.

Although that was written 32 years ago, nothing much has changed.

Herein lies a thought. There's some evidence that our brighter politicians are aware of the dangers of Bubblethink - perhaps more so than much of the media. Could it be, then, that the Westminster bubble describes the media more than politicians?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers