Chris Dillow's Blog, page 115

September 25, 2014

Mansion Tax: bugs & features

Some of the opposition to Labour's proposed mansion tax seems to me to be confusing bugs with features.

For example, in the Times (£) Janice Turner claims the tax will hit "shabby family houses" which have soared in price because of the property explosion. But this is precisely the virtue of land taxes. London's house prices have soared for several reasons, but none of them because of the efforts of their owners. It's fair to tax people if they reap a benefit with no effort. And as for £2m being "shabby", Hugo Rifkind's tweet was right:

Anybody who says "perfectly normal houses in London now cost £2m" is welcome to buy my perfectly normal house in London anytime they like.

Similarly, Allister Heath says the tax would force people on low incomes to sell up. But this too is a feature, not a bug. Forcing such people out of their homes would free up the houses for those who need them more - families or people who need to be close to where they work.It thus ensures a more efficient use of the housing stock.

Jay Elwes objects that it would be difficult to value houses. I'm not sure. We know the price at which houses changed hands, and it should be straightforward to apply an inflation rate to those prices. I suspect this is just an example of the status quo bias - an objection to policies simply because they don't exist. Imagine if we had serious land taxes and someone proposed a tax on profits instead:

Are you mad? Do you know how difficult it is to measure profits accurately, and how easy they are to fiddle or to shift overseas? Only a fool would want to tax profits rather than land.

However, I don't want to wholly condemn the tax's opponents. When he says that the tax is "an arbitrary confiscation of wealth", Mr Heath has a point in two different senses.

First, taxes on assets should be capitalized into prices; if people expect to pay a tax on an asset, they'll pay less for it. This provides a double blow to current owners of £2m properties; they'll both have to pay tax and they'll suffer a capital loss. But it means that the future rich who'll want to buy a mansion won't suffer at all. Sure, they'll have to pay a tax on their mansion. But they'll have bought the mansion cheaper than they otherwise would because of the tax. It's a wash. In this sense, the mansion tax penalizes today's owners of expensive homes whilst leaving tomorrow's owners unscathed.

Secondly, there'll be some beneficiaries of this tax. People who own homes slightly less than £2m could see a capital gain, as buyers of £2m+ house switch to slightly cheaper properties. (Here's what sub-£2m buys near me.) I reckon that people who own houses woth around £1.8m are quite well off. On both counts, then, I sympathize with Mr Heath; this does seem arbitrary.

The solution to the second problem is straightforward (in theory!). As Ben Southwood says, council tax could be rejigged to become more progressive.

The first problem, however, remains. One solution would be to raise income tax on the rich. But that would raise far more opposition than there is to a mansion tax.

September 24, 2014

Forget the deficit?

Despite his denials, I suspect that Ed Miliband "forgot" to mention the deficit in his speech yesterday for the same reason schoolboys forget their homework - because they don't care about it.

If I'm right, he has an excellent antecedent. Back in 1933, Maynard Keynes said:

Look after the unemployment, and the Budget will look after itself.

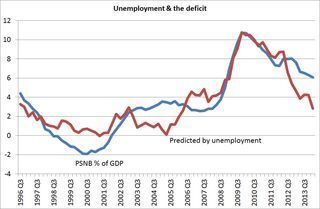

But is Keynes' saying still relevant? My chart shows the result of a simple test. It shows the regression of public sector net borrowing as a share of GDP upon the unemployment rate, plus lagged unemployment over the past 10 quarters.

I'm defining unemployment as the officially unemployed, plus the inactive who want a job: ONS data on this began in 1993, so the lags mean our data starts in 1996. And I'm using lags of unemployment because some taxes (such as corporation tax) only flow to the Treasury with a long lag.

My chart shows three things.

First, that there's a close relationship between the two: the R-squared is 75%, implying that Keynes was three-quarters right*.

Secondly, pretty much all the rise in the deficit between 2007 and 2010 is explicable by unemployment. In this sense, the deficit was cyclical.

Thirdly, in the last two years the deficit has been higher than unemployment would predict. You could interpret this as a sign of a "structural" deficit. But if you do, it's one that has emerged only since 2012. And it's no bigger than the "structural" deficit of 2005 - and you'll remember the great fiscal crisis of that year. Not.

In fact, I suspect there's a simple reason for this gap. It's simply that the drop in unemployment overstates the health of the economy. Joblessness has declined not just because the economy has grown buty because productivity has stagnated. This means we have not seen the rises in wages and profits we usually see when joblessness declines, and so tax revenues haven't risen as much as they should have.

In this sense, we might rephrase Keynes: look after unemployment and productivity, and the Budget will look after itself.

Now, I'll concede that I might be wrong here. Maybe there is indeed a "structural" deficit that requires significant fiscal tightening. But I'll need better evidence than estimates which are based upon the mumbo-jumbo idea of an output gap. And in the absence of such evidence, we should at least entertain the possibility that the deficit doesn't matter. Maybe therefore Miliband was right to forget it, as there are much higher priorities.

* I suppose one might argue that the relationship is the other way round, and deficits cause unemployment 18 months previously. Feel free to provide empirical evidence that this is the case.

September 23, 2014

How to attack Labour leaders

Dear political journalists.

Your job is to criticize Ed Miliband. Of course, this might be because he's doing a bad job. But it's also because you are well-paid and privately educated, and so naturally unsympathetic to most Labour leaders. You will, therefore, want to oppose him whatever he does.

In this regard, you can learn from your colleagues on the sports desk. After years of practice they have perfected the art of condemning Arsene Wenger regardless of facts or logic. Their tricks can be adapted to Ed Miliband, for example:

1. Everything can be redescribed; if a man walks on water, say he can't swim. When Arsenal played better in the second half than the first at Everton it was because Wenger got his tactics wrong in the first half, whereas when Chelsea did better in the second period against Leicester, it was because Mourinho gave a brilliant half-time team talk. You can do the same for Miliband. Redescribe his intelligence as nerdiness. And if he looks like being popular with Labour activists, say he is out of touch with "middle England" - where "middle England is the 5% of voters like you.

2. The double whammy. When Arsenal had Patrick Vieira, Wenger's teams lacked discipline. Now they have a better disciplinary record, they have a soft centre. The same trick works for Labour leaders. If they seem out of touch with voters, emphasize their weirdness. If not, accuse them of populism.

3. See problems where none exist. Just as every defeat for Arsenal is a crisis, so keep asking what Labour plans to do about the deficit, even though most economists and investors don't care.

4. Never look for reasonable motives. When Wenger said he would happily pay £42m again for Ozil, he was accused of being stubborn rather than of wanting to boost Ozil's confidence. Similarly, you must say Ed Miliband's inactivity during the Scottish referendum was due to weak leadership rather than to a desire to avoid someone else's mess.

5. Avoid details. Football pundits claim that Wenger can't coach defending - forgetting that only the money-launderers kept more clean sheets than Arsenal last season - without saying precisely how to improve the defence. Similarly, you should demand that Miliband appeal more to voters in the south, without saying how.

6. Confuse luck with skill. Pundits claim that Arsenal's long injury list down the years is due to Wenger's bad management rather than bad luck - though, heeding point 5, they never say precisely how. Similarly, you should say that falling unemployment shows that Labour's criticism of Tory austerity was mistaken, and not point out that this has only happened thanks to an unexpected collapse in productivity growth.

7. Ignore the fact that there are trade-offs. The pundits accuse Arsenal of defensive naivete because their fullbacks play high up the pitch. If they played deeper, however, the same gobshites experts would say Arsenal were over-run in midfield. The same trick works in politics. If Labour says little about the deficit, accuse them of lacking "credibility". If they have plans to reduce it, accuse them of tax bombshells and wanting to slash defence spending.

8. Never, ever mention the elephant in the room. Football writers (with the honorable exception of the gerat Matthew Syed) rarely point out that Wenger's relative lack of success in the last few years is because his rivals have spent hundreds of millions of pounds of stolen money. Similarly, you must never say that the biggest problem labour leaders face is that the power of the rich greatly constrains what any social democratic government can achieve. Pretend the game isn't rigged.

September 22, 2014

"Credibility"

At the end of an interview with Ed Balls this morning, Sarah Monague (02h 22m in) gave us a wonderful example of the ideological presumptions of supposedly neutral BBC reporting. She asked Nick Robinson: "It's about economic credibility here, isn't it?"

What's going on here is a double ideological trick.

First, "credibility" is defined in terms of whether Labour's plans are sufficiently fiscally tight*. This imparts an austerity bias to political discourse. There's no necessary reason for this. We might instead define credibility in terms of whether the party is offering enough to working people, and decry the derisory rise in the minimum wage as lacking credibility from the point of view of the objective of improving the lot of the low-paid.

Which brings me to a second trick. Credible with whom? We might ask: are Balls' policies credible with bond markets - the guys who lend governments money - or will they instead cause a significant rise in borrowing costs? Or we could ask: are they credible with working people? But neither she nor Nick presented any evidence about either group. The judges of what's credible seem to be her and Nick themselves - who, not uncoincidentally, are wealthy, public school-educated people.

This poses the question: what is the origin of this double bias?

It's tempting to say that it is a simple right-wing bias; why should people from public schools on six-figure salaries think that politics should concern itself with the living standards of ordinary people?

But maybe it isn't. What we're seeing here might be yet another example of an idea that's outlived its usefulness.

There was a time when the credibility of fiscal policy mattered; in the 70s and 80s, social democratic governments in the UK and France were constrained by the bond market vigilantes. But this is no longer the case. We live in a world of a savings glut and safe asset shortage. The bond vigilantes have gone home. Maybe Balls' looser fiscal policy might raise bond yields a little. But does this matter much when they are negative? However, Montague and Robinson haven't adapted to this new world, and - like all mad people in authority - are the slaves of some defunct economist.

So, I'm not sure what the reason for Montague's bias is. But I do know that the idea that the BBC is neutral is just...

* For more intelligent discussion of those plans, try this and this.

September 21, 2014

Capitalism & the low-paid

Is capitalism compatible with decent living standards for the worst off*? This old Marxian question is outside the Overton window, but it's the one raised by Ed Miliband's promise to raise the minimum wage to £8 by 2020.

First, the maths. This implies a rise of 4.2% per year; the NMW will be £6.50 from next month. However, as the NMW rises, workers' incomes don't rise one-for-one, because tax credits get withdrawn. Assuming an average deduction rate of 50% (it varies depending on whether workers have children - see chart 5.8 in this pdf), this implies a rise of 2.1% per year. However, if the OBR's forecasts are correct, CPI inflation will average 2% over 2015-20.

Miliband's promise, therefore, amounts to little better than a pledge that the incomes of the low paid won't fall in real terms - and not even that much, to the extent that inflation might exceed target.

Now, in fairness, Labour might well do more to help the low-paid by, say, increasing the generosity of in-work benefits. But promising to do this before the election would merely run into the question from dickhead journalists: "where will the money come from?" So it's best for Labour to under-promise.

Nevertheless, the raises the issue: what would serious policies to help the low-paid entail? I suspect they would require:

- Macroeconomic policies to boost employment. If you ensure a high demand for labour, you might eventually raise its price.

- A serious jobs guarantee; this would help give work to the less skilled, who might not benefit so much from higher aggregate demand alone.

- Policies to strengthen the bargaining power of low-paid workers. These could include stronger trades unions (pdf), but I'd add a citizens' basic income, which would give workers a guaranteed outside income, and so empower them to reject exploitative jobs.

This brings me to my opening question. Are these policies compatible with capitalism? On the one hand, yes - because higher aggregate demand would raise the mass of profits. But on the other hand, no**. For one thing, as Kalecki famously pointed out, macro policies to increase employment would weaken capitalists' political power by making business confidence less important for growth. And for another thing, more bargaining power for workers means less for capitalists. It's moot.

But this is precisely the debate we should be having. It could be that, whilst the constraints imposed by capitalism are tight, Labour might be over-estimating their tightness, and so will under-deliver for the low-paid.

* Note for rightists: As Adam Smith said, the notion of what's decent rises as incomes rise. And the fact that capitalism has massively improved workers' living standards in the past does not guarantee it will do so in future. As Marx said, a mode of production which increases productive powers can eventually restrain them. And as Bertrand Russell pointed out, inductive reasoning can go badly wrong.

** Simple maths might clarify. The profit rate, P/K can be expressed thus: P/K = Y/K x P/Y. Expansionary macro policy - especially in an environment of wage-led growth - would raise Y/K. But stronger workers' bargaining power would cut P/Y.

September 20, 2014

Economists as food experts

Simon Wren Lewis reminds me of Moe Szyslak.

No, I'm not trying for an improbable libel action. I'm referring to his call for a fiscal council. He says:

Politicians will believe anything that suits them. But what the independence referendum showed us is that voters have similar problems. As the campaign progressed the stronger the Yes vote became, and there is some evidence that this reflected additional information they received. As I suggested here, the problem is that this information was superficially credible sounding stuff from either side, but often with no indication from those who might have known better of the quality of the analysis.

There are ( at least) three relevant mechanisms here:

- Knowledge produces overconfidence. It's not just in politics that this is the case. It also happens when people are putting their own money at stake. For example, even well-informed investors are prone (pdf) to buying poorly perforning, high-charging funds because they erroneously believe that their knowledge gives them the ability to spot good funds.

- A selection bias. People get interested in politics because they believe that politics matters (like, duh). This means that those who speak on political affairs - not just professionals but blokes in pubs - are disproportionately likely to overstate the ability of policies to improve the economy when, in truth, as Simon says, "most of the time the macroeconomy stubbornly refuses to be impressed".

- Asymmetric Bayesianism. As we learn more about an issue, we learn the faults in our opponents' arguments whilst giving our own an easy ride. Thus, knowledge produces dogmatism.

For these reasons, even a quite well-informed electorate might have mistaken preferences.

Which is where I'm reminded of Moe. In The Gilded Truffle, he says: "Bring us the finest food you've got stuffed with the second finest."

The waiter replies: "Excellent sir. Lobster, stuffed with Tacos."

It's here that there's a role for fiscal councils. Think of them as food experts, telling us that the food we want might be expensive, bad for us or just not as tasty as we'd like - and, maybe occasionally, pointing us to cheap and tasty alternatives.

You might think that, in the IFS, we already have impartial fiscal experts. Sadly, though, its Mirrlees review has merely served as Exhibit A for Alan Blinder's famous remark, that economists have the least influence where they know the most. One case for putting a fiscal council onto a statutory basis is that doing so might cause people to pay more attention to it. Far from being undemocratic, such a council should improve the quality of democracy, by raising the quality of debate.

In this respect, its success requires two things. One is that its function be limited. If the council gets into the idiot business of forecasting, it will soon discredit itself.

The other is that the council should be explicit about the limits of what we know - for example that it's difficult to estimate Laffer curves precisely. The function of experts is not merely to introduce knowledge into the public realm, but also doubt.

September 19, 2014

Defending markets

I have often accused rightists of making a "small truths, big error" rhetorical trick - of using a small truth to disguise a big mistake. I fear, though, that this post by Richard Murphy shows that the left can do the same thing.

He points outthat the conditions required for markets to work optimally are extremely unlikely to exist in the real world.

This is true.

It is also irrelevant. Optimality is a massively demanding standard. if we were to scrap all institutions because they were sub-optimal, we'd have nothing left.

Nobody would seriously defend a market economy because it is optimal. Instead, the intelligent defence of markets is that they are (often) the least bad ways of coping with the fundamental problems of complexity, limited knowledge, bounded rationality and the (occasional?) human propensities for venality and greed.

For example, Hayek's defence of a market economy wasn't that it fulfilled the requirements for optimality; he described the textbook theory of perfect competition as "of little use." Instead, he said, markets were a way of aggregating dispersed information (pdf); countless traders and customers, taken together, know more than a central agency ever could. This, for example, is why prediction markets can be (pdf) more successful than individual pundits. And it's why computational experiments show that agents with limited rationality can produce efficientish markets. Under some circumstances, there is wisdom in crowds.

Similarly, when Smith wrote that "it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest" he was capturing the possibility that markets could channel greed for useful ends. By contrast, the argument against state control is that the state will be captured by the rich used used to serve their interests - a claim for which there is surely abundant evidence.

Now, of course, the notion that markets are always a less sub-optimal institution than the state is silly. How well markets work will vary from place to place and time to time, and often depend upon quite subtle differences in incentives and structure; sometimes, for example, bubbles occur in usually efficient markets. Most of us, I reckon, would favour tougher regulation of banks than greengrocers.

Personally, I feel a little embarrassed to say all this, as I think it's bleeding obvious.

But it's not just anti-market types such as Richard who don't realize this. Hayek's point about the virtues of disaggregated information-gathering is also underweighted by fund managers who rip off their clients by falsely claiming to be able to beat (pdf) the market, and by corporate bosses who think they deserve mega-million salaries for controlling big organizations.

It's insufficiently realized that the 1% and leftist anti-marketeers have a lot in common.

September 18, 2014

Distrusting politicians

One curiosity of the Scottish referendum campaign has been that polls show that Alex Salmond is less distrusted than other politicians. For example, when Yougov asked "how much do you trust the statements and claims made by the following people?" they found that 40% of Scots trust him whilst 55% don't. For Darling, the figures are 34-60; for Cameron 26-70; and for Miliband 25-67.

I say this is curious because good judges have plausibly accused Salmond of sophistry and deceit, whereas the charges of outright dishonesty against No campaigners seem less grievous to me. (Of course, many No claims might well have been wrong - but that doesn't imply dishonesty.)

Why, then, are the No campaigners so distrusted? Part of the answer, I suspect is a halo effect; we tend to attribute all bad qualities to people we dislike. Whilst this is natural, it is, however, not logical. For example, my opinion of Cameron is so low that I could be mistaken for a Tory MP, but I don't question his integrity. Rather, I think of him as Wilf McGuinness thought of George Best: "You can rely on George: he'll always let you down."

Another part of the story is that the expenses scandal discredited pretty much all Westminster politicians. I fear, though, that inferring from this that individuals are dishonest is another example of failing to see emergence. The story of the scandal was one of stupid rules and procedures and peer effects, not (mainly) of individuals' corruption.

Yet another part of the answer lies in lazy cynicism. "They're all the same - in it for themselves", "why is this lying bastard lying to me?" Such commonplace cliches are anti-political not just in the trivial sense of being hostile to politicians, but in the deeper sense of failing to see that people can have different policies and values to you and yet be entirely decent and honest.

But, of course, we shouldn't just blame voters. What we're seeing here is a downside of Hotelling's law. For years, the Westminster parties have scrapped for the "centre ground" using the same top-down managerialist ideology. This means that the discrediting of some politicians discredits all: if you stand close together, it'll be easy for people to tar you with the same brush.

This error though, can be avoided. Werner Troesken points out that peddlars of quack medicines (pdf) prospered for decades. They did this by investing in advertising and product differentiation - often employing great musicians to do so - so that the failure of one product, far from discrediting others, merely led to extra demand as people looked for alternative cures.

And herein lies a reason for the comparative success of Alex Salmond and Nigel Farage. In distancing themselves from the "Westminster elite" they have (partly) avoided being discredited by association. In this sense, they are emulating snake oil salesmen. As for any other parallels, well...

September 17, 2014

What Phillips curve?

Economists have recently been abandoning once-core concepts in macroeconomics such as the money multiplier and IS-LM model. This week's figures remind me of something I'd also throw on the bonfire - the Phillips curve.

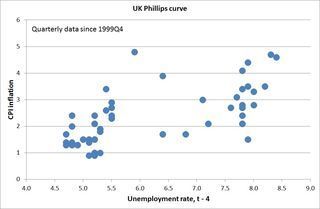

My chart shows the point. It shows that the relationship between the official measure of unemployment and CPI inflation four quarters later has been perverse. Higher unemployment has led to higher inflation, not lower as the Phillips curve says.

If we control for inflation expectations, as surveyed by the Bank of England, this perverse relationship weakens - but there remains a statistically significant positive relationship between lagged unemployment and inflation.

One reason for this might be that the official measure of unemployment is inadequate. It excludes the 2.3 million of "economically inactive" people who'd like a job and the 1.3 million of part-timers who want a full-time job.

If we take this wide measure and control for inflation expectations, we do get a negative relationship between unemployment and CPI inflation. But it is not statistically significant (p value = 25.7% for quarterly data since 1999Q4). Nor is it economically so; a one million drop in the wide measure of joblessness is associated with only a 0.16 percentage point rise in CPI inflation.

I'd suggest three reasons for this weak relationship. It's because the tendency for a tight labour market to raise wage and price inflation is offset by three other mechanisms:

One is globalization. In a small open economy, inflation depends upon inflation overseas and the exchange rate. Euro area deflation and the strong pound in recent months have offset falling unemployment. As one of the better macro textbooks says:

In an open economy, there is a range of unemployment rates consistent with the absence of inflationary pressure. (Carlin and Soskice, p343)

Secondly, fluctuations in aggregate demand aren't the only story. Supply shocks such as commodity price moves or changes in productivity growth can generate positive correlations between unemployment and inflation.

Thirdly, inflation isn't necessarily cyclical. In a classic paper in 1986, Julio Rotemberg and Garth Saloner pointed out that price wars were more likely (pdf) in booms than slumps. The fact that supermarkets are cutting prices now is consistent with this.

Now, all this said, I'll concede that the conventional Phillips curve might exist outside the UK - though even in the US it is rather flat. For practical purposes, however, unemployment tells us very little about future inflation.

September 16, 2014

Coping with complexity

Martin Wolf says something that I'm in two minds about:

People have to understand, when they're being taught economics, how little we know, how limited our data are, and how unbelievably complex our economic and financial system is.

I think people have to begin with profound humility and know an awful lot of economic history, as I've suggested. And they have to be told every day, "What I've just told you is almost certainly wrong."

I'll join him on the barricades in saying that the economy is a complex system which is inherently unforecastable and so we must be humble about some policy recommendations such as the precise stance of fiscal or monetary policy.

However, it doesn't follow that economists must be humble. As Herbert Stein said: "Economists don't know very much; other people know even less." Sometimes, the solution to complexity is simplicity.

I reckon that we do know three general principles about coping with complexity:

1. Ensure you have the flexibility to respond to shocks. This is one under-rated virtue of markets; whereas companies can die suddenly, markets rarely do. Networks are often more flexible than hierarchies.

A key thing here is to ensure that components are substitutes rather than complements, so that the failure of one doesn't jeopardise all. Phones4U, for example, has collapsed without widespread ill-effects whereas RBS's collapse created a crisis. One reason for this is that Phones4U has many substitutes - we can get phones elsewhere - whereas RBS had complements; its failure dragged other companies down by choking off credit. As Charles Jones has pointed out, one reason why some countries are poor is that they rely too much upon complementarities, so that the failure of one component such as a port or power plant can plunge whole regions into poverty. The banking crisis reminded us that rich economies also suffer this problem.

For me, this is one argument for Robert Shiller's macro markets. If we can't see recessions coming, we should cushion ourselves against them by using insurance markets rather than relying upon macro policy. Flexibility is better than futurology.

2. Be aware of cognitive errors. If you can't make correct decisions, at least avoid the best-known ways of being wrong.

3. Don't optimize, but satisfice. In a complex world, we often lack the data to make optimal decisions. But we can be roughly right rather than precisely wrong.

For more concreteness, let's apply these principles to financial planning - a field where economists certainly have useful things to say. They imply:

1. Always hold some cash. This protects you from correlation risk and liquidity risk, and ensures that you'll never have to be a forced seller.

2. Be aware of the common mistakes investors make, such as trading too often; being led by peer pressure into bad investments; or becoming too risk-tolerant in the spring and too risk-averse in the autumn.

3. Don't try and chase every penny, but instead find an asset allocation that's good enough. This means holding tracker funds and avoiding actively managed ones, where you're certain to incur high fees but far (pdf) from certain to out-perform.

I suspect, therefore, that economists don't have to be that humble - at least once we recognise that the job of economists is not to give futurological advice to empty suits, but rather to help ordinary people make better choices.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers