Chris Dillow's Blog, page 118

August 7, 2014

Two politics

"Local politician considers becoming MP" should, be rights, be a story only of interest to local newspapers. If the national media take an interest, it should only be to ask whether a man who has twice been sacked for dishonesty and who has conspired with a serious criminal is fit to enter parliament.

Which poses the question: why was this story the lead item on Radio 4's news yesterday and in the Times today, and in hagiographic terms?

Partly, it's because the media is so London-centric that it regards the North Circular Road as an iron curtain. But there's something else going on. It's that there are two types of politics which have become so distant from each other that they shouldn't share the same name.

Politics1 is politics in its traditional form. It asks how relations between citizens should be regulated.

Politics2 is the subject of political journalism in the media. And this is often a different thing entirely, being focused upon personalities and presentation. It is that makes Mr Johnson political2 news, because he is a "character" who fulfils a major function of politicians - to provide entertainment for journalists*.

It's become a cliche to say that politics2 is a soap opera. But this is an insult to soaps, which contain diverse and sometimes sympathetic characters, and which often raise important issues.

Even when politics1 and politics2 should coincide - for example on the Scottish independence debate - they don't: Radio 4's PM programme, for example, tried to reduce it to a matter of Salmond's and Darling's personalities. The fact that the BBC gives so much publicity to Mr Johnson and little to serious MPs such as Jesse Norman or Jon Cruddas shows that politics2 has displaced politics1. It's no wonder, then, that so many social and economic changes are happening without politicians' noticing.

I think of this as a political blog. But what's striking is that the things that I consider to be political1 questions are so rarely discussed by mainstream politicians, and certainly don't form the substance of the BBC's political reporting: is the wealth and power of corporate bosses justified? What should be the respective domains of market, hierarchy and cooperation? what is the relationship between institutions, culture and morality? What role should emotion, ideology and irrationality play in public life? How do bounded knowledge and cognitive biases shape politics?

For me, questions such as these (and there are more - these are just some of my interests) should be the basis of politics. But they are largely ignored.

This ignorance serves a deeply reactionary function. In keeping fundamental issues off the agenda, whilst promoting an image of politics as a wrestling match between "characters", politics2 helps to preserve the power and wealth of elites by failing to ask the questions that might undermine their legitimacy.

* I'd even put another of the week's biggest news stories - the resignation of Baroness Warsi - into this category, because it is about what pose to strike about the middle east: would Benjamin Netanyahu ever say "Best seek peace with Hamas, lads, because the Brits are cutting up rough?"

August 6, 2014

Peer effects in companies

"Corporations are people" said Mitt Romney. He was more right than he knew, because two new NBER papers by Christopher Parsons and colleagues show that companies are like people, in the sense that they are prone to peer effects:

We find that a firm's tendency to engage in financial misconduct increases with the misconduct rates of neighboring firms. This appears to be caused by peer effects, rather than exogenous shocks like regional variation in enforcement. Effects are stronger among firms of comparable size, and among CEOs of similar age.

In this sense, firms are just like ordinary people in that they are more likely to commit crimes if their peers do. This might be one reason why so many banks were involved in fixing Libor and in mis-selling PPI.

We find that a firm's investment is highly sensitive to the investments of other firms headquartered nearby, even those in very different industries...

We, of course, cannot rule out the possibility that area co-movements arise because of irrational herding, which would be the case if managers put too much weight on the beliefs of their neighbors.

Again, there's a direct analogy here with people;there are peer effects in individuals' spending, perhaps in part because their expectations are infectious.

There is, I suspect, an important political point here. There's a tendency to defer to "business leaders" as if they have superior insight into the economy; how often are they uncritically interviewed on the Today programme, for example? Such deference is misplaced. Rosewell and Ormerod have shown that "bosses have very limited capacities to acquire knowledge about the true impact of their strategies." And Charles Lee and Salman Arif have shown that higher capital spending leads to disappointing profits, consistent with it being driven by sentiment rather than a rational assessment of profitable projects. We should read Parsons' research in this tradition. It suggests that corporate bosses are not wise and rational leaders but are instead as easily led as impressionable teenagers.

So, why are we paying them so much?

August 5, 2014

Decorporatization

In the day job, I've coined a newish word - decorporatization.

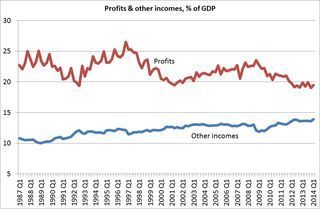

My chart shows what I mean. It shows that in recent years we haven't seen just a squeeze on wages, but also a squeeze on profits; the share of these in GDP has fallen recently. One reason for this is that the incomes of the self-employed - measured by the ONS as other incomes - have increased. This hasn't happened because the self-employed are raking it in, but because there are so many more of them.

This is what I mean by decorporatization; we're seeing a shift from corporate sector activity to the self-employed.

Some of this might be due to firms employing freelancers and one-man subcontractors rather than staff - perhaps because transactions costs have fallen. However, whilst this might have have increased profits for particular firms, it hasn't increased them in aggregate.

What might also be going on is a shift in consumption patterns. For example, if we pay a gardener £100 we have £100 less to spend in the corporate sector. And it might also be that there are countless small-scale shifts in spending happening: for example from supermarkets to farmers' markets; from banks to P2P lending; from shops to eBay; from removal companies to men with vans; from chain coffee shops and restaurants to independent ones and pop-ups. And so on. You migh think these are small changes. But they can easily add up to a couple of percentage points of GDP.

I don't know if these changes will continue. Maybe Rick is right and that as the economy picks up, poorly paid under-employed freelancers and handymen will return to employment thus reversing these trends. Or maybe they won't, perhaps because more people will want to escape corporate drudgery and downshift whilst the fashion for artisanal goods and services will continue.

But futurology isn't my point. Instead, there are two others.

One is that culture matters for macroeconomics even over shortish periods. A cultural change towards self-employment - both the supply thereof and demand for its goods - is affecting profits now.

Secondly, those hipster twats who think they can sock it to "The Man" by tweaking their "lifestyles" aren't as stupid as they look. Small-scale changes can add up to significant discomfort for big capitalism. As I've said, social change can happen without formal politics realizing it. The transition from feudalism to capitalism didn't happen quickly or because of nationally organized political protest ("What do we want? Less socage! When do we want it? Now!") so perhaps the transition from capitalism* won't either.

* Clarification for the hard of thinking: by capitalism I mean a system of ownership, not a market economy.

August 4, 2014

Economists & the public

In a comment here, I propose the creation of a new job, or jobs - professors for the public understanding of economics, analogous to the professorships at Bristol and Oxford which do the same for science.

I'm not thinking that such jobs should necessarily be part of a free market priesthood; there's more to proper economics than "Markets work, ner, ner". Instead, the role would be to try to inform the public of what economists know and don't. This would consist of at least three objectives:

- to narrow the distance between the academic consensus and public opinion which is especially wide in the cases of fiscal policy and immigration.

- to enhance the public image of economics - for example, by demonstrating that there are rough consensuses on many issues, and by telling people at every opportunity that macroeconomic forecasting is not proper economics.

- to help people make better personal financial decisions by promoting financial literacy and by alerting people to the systematic cognitive biases that cause bad decision-making. For me, economics is not just - or even mainly - about policy, but about helping people with everyday decisions. There's tons that economists can do here.

I've no doubt that such positions are desirable. What I doubt is whether they are feasible. Even if such jobs existed, I'm not sure their holders could succeed. There are (at least) four big barriers here:

1. Incentives. The traditional "publish or perish" academic environment has incentivized new research over the public engagement I have in mind. It's not clear how far this will change with the REF's inclusion of "impact" as a factor in determining department's funding.

2. The "gee whizz" factor. Scientists have an advantage over economics in that they can highlight new discoveries or the wonders of the universe. Economics is inherently less exciting - in part because it often reminds people that there are very few free lunches and no easy road to riches.

3. Public prejudice. People - and the media - don't want to be told that the facts don't fit their prejudices. Telegraph readers won't want to hear evidence against austerity, nor Guardian readers evidence that markets sometimes work. And as Jonathan Portes knows, telling people facts about immigration is like reciting poetry to a pig.

4. Vested interests. Economic literacy would be a threat to many firms. Lobbyists for tax breaks would fall foul of the fact that the best tax systems are flat(tish) and simple; payday lenders would suffer if people knew the power of compounding; and few high-fee fund managers would survive in a world where investors knew that the efficient market hypothesis was a good working assumption.

What I'm saying here is the counterweight to what I said yesterday - as Jon Elster said, the opposite of a great truth is sometimes another great truth! Yes, there is a gulf between academic economists and the public. But the blame for this doesn't lie with academics alone.

August 3, 2014

What use are academics?

What are academics good for? asks Simon Wren-Lewis. I'm tempted to reply along the lines of Edwin Starr - absolutely nothing, as least for British academia.

Simon is right to say that the academics are correct to take a dim view of austerity. However, many of the same textbooks that tell us that austerity doesn't work also perpetuate guff about the money multiplier and central banks creating money. Here's Simon:

The textbooks are out of date. The core of what is taught to undergraduates has not changed in fifty years, whereas macroeconomic thinking has changed substantially. However we are not using fifty year old textbooks. You will actually find a great deal of the more modern stuff in the textbooks, but essentially in the form of add-ons. So first students are taught that central banks fix the money supply, and then they learn about Taylor rules.

The non-economist can surely be forgiven for not giving sufficient credence to the anti-austerian view, when the same sources are plain wrong on another matter*.

In this sense, academics are failing us. The other day, I wanted to know: what is the present state of research on the link between education and economic growth? Where would I go to answer this, or questions like it? Yes, there's the great Journal of Economic Perspectives and the partially paywalled Journal of Economic Surveys. But these are international ventures. Where are the British academics who are content to do similar services?

I have two other gripes.

First, many academics are idiots, in the ancient Greek sense of the word: they don't participate in public life. It's still the case that only a minority blog, for example. Yes, the few that do are great - but we're talking quality not quantity here.

Secondly, the quantity of research is actually rather low. I'm in the unusual position of being a consumer of academic work. A large chunk of my day job (and blogwork) consists of scouring Repec, SSRN, IZA and CEPR for new research. Remarkably little of what I find comes from British academics. (Some still persist in keeping their work behind paywalls, which I regard as pure criminality.) Granted, I might have a biased perspective here; my interests are in finance, labour, macro and behavioural economics and perhaps UK academia is strong elsehwere. But I'm not sure this fully exculpates them.

Now, I'll concede immediately that these flaws - if such they be - aren't wholly imdividual failures. It's likely that, just as the financial system can cause rational individuals to produce institutionalized stupidity, so the academic system - with the twin pressures of the REF and teaching burdens - cause academics to become institutionalized idiots.

But is this the whole story? Might it also be that academic culture militates against academics contributing more to public understanding? A culture of pedantry, maximally ungenerous reading (and fear thereof) and obsession with methodology aren't conducive to an outward-looking contribution to open public life.

I say all this in a mood of sorrow and relief. Sorrow, because a potentially great resource is being wasted. Relief, because I might well have become an academic if there had been jobs available in the 1980s. Very often, I say a little prayer of gratitude to Lady Thatcher for saving me from that fate.

August 2, 2014

Limits of rationalism

The other day, I sympathized with Oakeshott's anti-rationalism. Bang on cue, rationalist-in-chief Richard Dawkins showed one of the weaknesses in rationalism. He tweeted:

Date rape is bad. Stranger rape at knifepoint is worse. If you think that’s an endorsement of date rape, go away and learn how to think.

When some objected to this, he replied:

I don’t think rationalists and sceptics should have taboo zones into which our reason, our logic, must not trespass...

I deliberately wanted to challenge the taboo against rational discussion of sensitive issues.

What this misses is that taboos exist because humans are emotional creatures. We feel upset and disgust, and taboos exist to protect us from such feelings. Introducing rape gratuitously into a public discussion upsets some people unnecessarily. Etiquette dictates that we don't do this - just as it dictates that, on meeting Professor Dawkins, one should say "hello" rather than "you're a cunt aren't you." And disgust, like it or not, is the basis for some moral judgments - such as the belief that some things such as human organs or sex be not traded in markets.

Demanding that there be no taboo zones and that reason and logic go everywhere is, in this sense, a demand that people be dessicated calculating machines devoid of emotion. Even if this were desirable - which is very dubious - it is a futile call.

Nor is it obvious that the emotions which give rise to taboos can be subjected to the tribunal of reason. David Hume, for one, thought not:

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them...

Where a passion is neither founded on false suppositions, nor chuses means insufficient for the end, the understanding can neither justify nor condemn it.

I'll confess that this is true for me; my antipathy to inequality is, at root, an emotional one and my apparently rational arguments are the slave of that passion. I suspect - though cannot prove - that the same is true of Dawkins. Reading The God Delusion gives me the impression that Dawkins is motivated by an emotion of disgust at some of the effects of religion. I happen to share that feeling in many ways, but it is a feeling.

Here, I suspect, Dawkins is being inconsistent. What he's demanding is not so much that everyone be dispassionate but that they share his disgust at some things and his lack of disgust at others. He's complaining: "Why can't everyone be like me?"

And this brings me back to Oakeshott. The rationalist, he wrote, is:

something of an individualist, finding it difficult to believe that anyone who can think honestly and clearly will think differently from himself...

His ambition is not so much to share the experience of the race as to be a demonstrably self-made man.(Rationalism in Politics, p6-7)

In this sense, rationalism is close to narcissism.

August 1, 2014

Poverty: structural or individual?

Is poverty structural or due to individuals' failings? Matt Bruenig and Noah Smith are debating this. I'm inclined to agree with both of them.

I agree with Noah that the two are not mutually exclusive. A quick thought experiment shows this. Imagine a dictator were to set the distribution of incomes so that a few were very rich, many did OK but that a big minority were poor. And he then allocated positions in this distribution on the basis of various psychometric tests for intelligence, laziness and character. Would poverty in this society be due to structures or individuals?

Obviously, to structure - because the dictator has set the structure of incomes so that some are poor.

Obviously also to individuals - because there is a perfect correlation between poverty and low intelligence or other character failings.

The distinction, then, isn't robust.

Another thought experiment might help us distinguish the two. What would happen if everyone were to become intelligent, educated and hard-working?

The "poverty is individual" brigade would say that some form of Say's law would lead to the creation of sufficient good, well-paid jobs to eliminate poverty. The "poverty is structural" band would say that this won't happen, because inequality, deskilling and unemployment are inherent structural features of capitalism, which would condemn some to (relative) poverty even if we were all smart and employable.

What's the empirical evidence here? Immediately, we run into a problem. The research on the links between human capital and aggregate growth, whilst large, is not conclusive (pdf). On the one hand, Erik Hanushek among others thinks there might be big macro-level payoffs to higher cognitive skills. But on the other, there's lots of scepticism about the link between education and growth. Bryan Caplan's reading of the evidence is that the response is "low" - and Middendorf and Krueger and Lindhal agree (pdf). This is consistent to the private payoffs to education being due to signaling - which implies that it is one's relative, not absolute, level of education which determines one's income. If so, better education for all won't raise incomes much.

All this said, two bits of evidence - on top of my priors! - makes me side with Matt in believing that mass upskilling won't eliminate relative poverty.

1. Graduate over-education is significant in most countries. This suggests that Say's law doesn't work; good jobs haven't increased fully in response to a supply of educated workers.

2. There's no correlation between inequality in human capital and in incomes, either across countries or over time. This is inconsistent with human capital-based explanations for inequality, but consistent with the view that inequality is due to inequalities of power.

Personally, I suspect that the "poverty is individual" view owes a lot to ideology: system justification and the just world fallacy cause people to blame the victim. Actually proving this beyond doubt is, though, perhaps impossible.

July 31, 2014

Am I a Tory?

Am I a Tory, or is Jesse Norman a socialist? I'm prompted to ask because the other day he reminded me of his superb lecture (pdf) on Burke and Oakeshott.

What I mean is that, as Jesse says, both men, in their different ways, supported tradition against rationalism. This anti-rationalism, says Jesse, is "one of the central intellectual roots of conservatism through the ages."

That small c in "conservatism" is well chosen. Take three examples:

- You can read Harry Braverman's account of deskilling - which is as relevant today as ever - as being in this tradition. He's defending traditional craft skills against rationalist scientific management. Except that he's a Marxist.

- In the miners' strike, it was leftists who supported traditional communities against "sophisters, economists and calculators” who wanted to close the pits. (The fact that the sophisters' sums were wrong merely reminds us that rationalism and rationality are two different, and opposed, things.)

- Oakeshott's complaint in Rationalism in Politics (pdf) that rationalists elevate their "reason" over traditions and institutions can easily be read as supporting resistance to the managerialist assault upon universities. Such resistance is, I suspect, found more among leftists than Tories.

Jesse continues:

Rationalism can be seen in totalitarian societies, which seek to capture and organize the staggeringly diverse potential of human beings, and frame it on some Procrustean bed".

It certainly can. But for me, managerialist rationalism is also totalitarian, in the sense both that it wants to extend to places such as universities where it is unwarranted, and that it seeks to suppress diversity in favour of conformist careerism.

So, it seems that me, Jesse, Burke and Oakehott have much in common. And, indeed, Jesse is well aware (pdf) that crony capitalism and excessive CEO pay are inconsistent with conservative tradition he praises.

Where, then, do we differ? On at least two points.

First, I'm not so sure that Westminster politics can restrain crony capitalism whilst supporting free markets or what Jesse calls real capitalism. There are very powerful forces which mean that a free market economy tends to degenerate into cronyism.

Secondly, I don't regard rationalism merely as an intellectual defect. Instead, it serves an ideological function; it tries to justify the power of elites. As Alasdair MacIntyre wrote:

Do we now possess that set of lawlike generalizations governing social behaviour of which Diderot and Condorcet dreamed? Are our bureaucratic rulers thereby justified or not? It has not been sufficiently remarked that how we ought to answer the question of the moral and political legitimacy of the characteristically dominant institutions of modernity turns on how we decide an issue in the philosophy of the social sciences...

The realm of managerialist expertise is one in which what purport to be objectively-grounded claims function in fact as expressions of arbitrary, but disguised, will and preference. (After Virtue, p87 & 107)

I don't, though, want to emphasise too much the differences between me and Jesse. I just want to note that antipathy towards managerialism is based upon a wide and powerful intellectual tradition.

Another thing: Jesse commends Burke's statement that “Circumstances ... give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour and discriminating effect”:

The practical public reasoner — let’s call him or her the politician — must determine what the relevant circumstances are which make Avthe right policy to achieve it. A similar set might imply policy B, or a further set policy C. An obvious policy A may fail depending on circumstances, while an unobvious policy B succeeds".

But this is what I am getting at when I urge people to think about mechanisms rather than models - because mechanisms are local and partial and vary according to circumstance. And this is no mere theoretical point. The reason why I (and Simon I suspect) are hostile to Osborne's fiscal austerity is that whilst austerity might be justifiable in some circumstances - if interest rates are high - those circumstances are not here and now.

July 30, 2014

The economic base of virtue

ResPublica's call for more virtue in banking looks like it is out of step with our times. This is an indictment not of ResPublica, but of our times. In fact, virtue is necessary for a healthy free market economy because virtuous men do the right thing without law, and so virtue is an alternative to an arms race between ever-increasing regulation and ever more cunning attempts to game such regulation. Free markets, in this sense, need a moral framework.

This poses the question: what is the economic basis of virtue? If you think this is a Marxian question, you'd be only half right. When Deirdre McCloskey says that markets promote virtue and Dan Ariely says that exposure to centrally planned economies promote cheating, they are agreeing (rightly) with Marx that "the mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life."

Now, we know that bankers have been serial criminals. This tells us that there is something anti-McCloskeyan about the industry - that it breeds vice not virtue. But what? Here are six possibilities:

1. Short-term incentives. Annual or quarterly targets for sales or profits encourage people to meet targets now even if this means breaking rules: why bother helping your employer avoid a fine in a few years' time if you fail to make your targets and are sacked before then? Such targets thus create institutionalized criminality - in the sense that future punishments are discounted so heavily as not to be a disincentive. The Bank of England's proposals to claw back bonuses are an attempt to address this problem.

2. Whereas McCloskey might be right that competition for customers encourages virtues of trustworthiness, competition between traders doesn't. It instead breeds a dog-eat-dog mentality.

3. Neoliberalism can be performative; it doesn't just describe the world, but creates it. If you claim that people are amoral and self-interested and that government regulation is inefficient and undesirable, people might act in an amoral way and seek to evade regulation. And if you believe a (misreading?) of Friedman, that "The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits" you will aim to maximize profits, come what may.

4. Mere proximity to money can encourage unethical behaviour, and self-interestedness (pdf).

5. Selection effects. Hierarchies can select in favour of some vices such as narcissism, overconfidence, and psychopathy.

6. Diffused pivotality. Big organizations can encourage vice by removing individual responsibility; we can justify behaving badly by believing that we're doing what the boss wants or that if we didn't do it, someone else would.

Now, I'm not claiming that these mechanisms are found exclusively in banks and nowhere else; I suspect that 5 and 6 help explain Ariely's finding that centrally planned economies encouraged cheating. Instead, what I'm suggesting is that there are some mechanisms - which are stronger and more prevalent in some places than others - which undermine virtue. To this extent, Alasdair MacIntyre is right and McCloskey wrong: we lack the institutional and cultural basis for an ethics of virtue.

In this context, ResPublica might have a point in advocating more diverse ownership and governance systems - because some of these might do a better job of promoting virtue than existing structures.

I don't know if they will. But I do know ResPublica is asking the right question, of how to promote the virtues in which a free market does serve the public good. The fact that so few people are taking up this point - preferring instead cheap sneers at the (albeit silly) call for bankers' oaths - makes me suspect that some on the right are more interested in shilling for the rich than in promoting a free market economy.

July 29, 2014

The productivity silence

Simon Wren-Lewis wonders why the government has been so silent about stagnating productivity. I suspect there's a simple reason for this: you don't look a gift horse in the mouth. The drop in productivity growth has saved Osborne a massive embarrassment.

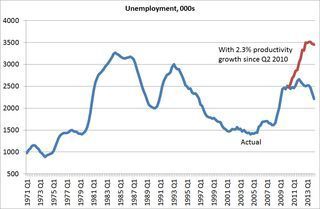

To see this, consider a counterfactual. Imagine that productivity (defined as GDP divided by total employment) since the general election had grown by 2.3% per year - its average from 1977 to 2007 - and that output had followed the course it actually has*. If this had happened, employment would now be 2.48 million lower. If half of this number were counted as officially unemployed, there'd be over 3.4 million registered as unemployed. And unemployment would have topped 3.5 million last year. That would be a post-war record.

Now, this would not mean that the Tories would have admitted that austerity had been a horrible error. I suspect that, in this scenario we'd be hearing a lot more about the damage done to the UK from the euro area's weakness. And Tory lackeys would be claiming there had been an outbreak of mass laziness; as we're seeing in other contexts, some people will defend any atrocity if it is committed by their own side. Even so, though, the productivity stagnation means that Osborne has dodged a bullet. It's been a massive stroke of luck for him.

Or has it? One could argue that austerity has contributed to the productivity slowdown in at least four ways:

- A tougher benefit regime has forced the unemployed to look for work, thus bidding down wages.

- Cuts in public sector jobs have reduced real wages and so encouraged some firms to substitute labour for capital.

- Low interest rates have allowed inefficient "zombie companies" to stay in business. This has depressed productivity in the same way that keeping injured soldiers alive reduces the average health of an army.

- Standard multiplier-accelerator effects mean that austerity depressed private sector capital formation, and the subsequent lower capital-labour ratio has reduced productivity.

I suspect that, except for the first of these, there might be something in these mechanisms. But perhaps not enough to explain all of the massive slowdown in productivity.

And, in truth, I suspect the Tories agree. Back in 2010 none of them said "Sure, austerity will depress output growth, but it will also depress productivity and so reduce unemployment." And even now none of them are claiming credit for the productivity slowdown.

But unless they do make these claims, they cannot - by the same reasoning - take credit for falling unemployment. This is because unemployment is lowish (on the official measure) and falling solely because of the productivity slowdown, and not because of strong output.

In this sense, the Tories' silence about productivity is because they are doing what decent people do - they are keeping quiet about some extraordinary good fortune.

* Is this scenario plausible? You could argue that it's not, because higher unemployment would have depressed consumer spending - though this only strengthens my point that the productivity slowdown has been a gift to the Tories. Alternatively, you might argue that productivty has been weak because output has been weak. However, the fact that productivity hasn't risen even as output has recovered renders this claim less plausible than it was a year ago.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers