Chris Dillow's Blog, page 122

June 18, 2014

The poor white problem

Why do poor whites do so badly at school? For example, only 32.3% of white British eligible for free school meals get five or more "good" GSCEs, whereas 52.% of Asians eligible for them do so and 48.2% of blacks do (Excel table here, via Sam).

Here's a theory.It rests on two premises:

- ability to pass exams and earn a living is highly correlated between parents and children, as Greg Clark suggests. For our purposes, it doesn't matter whether the transmission is via genes or culture.

- ethnic minorites are more likely than white British to be underpaid relative to their abilities. This might be because they suffer labour market discrimination (pdf), or because immigrants are more likely to be over-educated for their jobs than natives.

These two premises alone would generate a pattern in which poor white British do worse at school than ethnic minorities. This is because many poor minority children will come from good-ability parents who happen to be poor, whereas the white British will be more likely to come from lower-ability parents. And insofar as ability is inherited, minorities will then tend do better at school.

Now, neither left nor right will like this. The left will object to the assumption of a high inter-generational transmission of ability, and the right to my highlighting of racial discimination in labour markets. And managerialists will object to the apparent fatalism.

But it doesn't matter what you like. What matters is what's true. Is this theory?

Perhaps the strongest evidence against it pointed out by the Education Select Committee (par 44 of this pdf) - that there are massive regional variations in poor whites' attainment. For example, in Peterborough only 12.6% of whites eligible for free school meals get five good GSCEs, whereas in Lambeth almost half do. This huge discrepancy, says Adam Bienkov, suggests that where poor whites do badly it is because of poor schools rather than a lack of inherited ability.

Undoubtedly, this is part of the story. But I'm not sure it's all.

For one thing, in most (not all but most) of those local authorities where poor whites do well at school, poorer ethnic minorities do even better. For example, in Lambeth 49.6% of poor whites get five good GSCEs, but 57.7% of poor minorities do. (Annex 2 here). And even in Lambeth, poor whites do worse than the average poor Asians across the whole country.

And for another thing, it might not be fully possible for the rest of the country to emulate London's success. Insofar as better teachers would rather work in London than in Peterborough, poor whites in the latter are at a disadvantage. And as the JRF has complained, many schemes aiming to improve poor kids' achievements have been "a proliferation of ‘hopeful’ interventions with unknown effectiveness".

However, I don't mean this as a counsel of despair. I do so instead to repeat what I've said before - that if we want to improve the life-chances of the worst-off, the answer lies not just in investing in education, but in more income redistribution.

June 17, 2014

History's winners

I know it is usually the epitome of lazyblogging to point out the deficiencies of Louise Mensch's thinking, but there's something she tweeted recently (via) that deserves attention. Objecting to the continued backlash against the Sun's despicable coverage of Hillsborough, she said:

Nobody at the Sun was bloody even working there then. They were mostly kids and teens. It's absolutely immoral to blame them.

This is wrong. Put it this way. Why does she (and her colleagues) work for the Sun rather than simply blog on their own? The answer is obvious - the Sun has a big, monetizable readership that Ms Mensch couldn't create for herself, and this allows her to earn more from writing for the Sun than she could from blogging.

But why does the Sun have this advantage? It's because it built it up over time. Ms Mensch is profiting from the Sun's history. And if she wants to benefit from that history, she can hardly complain when others point out that the history is a less than glorious one.

But here's the thing. What's true of Ms Mensch is true for all of us who work for big, old organizations. Why do I get paid by the Investors Chronicle but not for blogging? It's not because my blogging is mere hot air whereas my day job isn't. Nor is it because I have ability when I write for the IC but not when I blog. Instead, it's because my writing for the IC generates a useful and monetizable match between my skills (such as they are) and my employers' vintage organizational capital. My wages are not a pure return to my skill - if they were, I could be paid for blogging too - so much as a share of that monetizable match.

For most of us, skills alone don't generate income; it is instead the match between skills and organizations that do so. This is why Wayne Rooney earns so much more than Tom Finney did. Ms Mensch gets (I presume) a decent wage from the Sun because there's a good match between writing shit and selling shit.

Most of us owe our salaries to history - to the existence of organizations which have built up monetizability over time.

It's in this context that Ms Mensch's error is a widespread one. She sees people as individuals detached from history. But we are not. Not only are we shaped by history, but we owe our wealth or poverty to history too.

This is trivially true of the differences between nations. I'm rich and the typical Burundian is poor not because I'm clever and hard-working whilst he isn't but because I was born in a country with three centuries of economic growth behind it and he wasn't.

It is also true of differences between people in the same nation. Imagine we'd had no social or technical change since medieval times. Then me and Ms Mensch wouldn't earn much, whereas the otherwise unemployable meathead who's good in a fight would do OK. But because we've had such change, we're doing OK and the meathead is on the dole. We've benefited from centuries of literacy-biased technical change just as some folk more recently have benefited from maths-biased technical change.

We recently - and rightly - commemorated the heroes who fought at D-Day. But we don't just owe our good fortune to them, but to the millions of our predecessors in the last few centuries who contributed to economic growth, to companies, and to the institutions which sustain and enhance our well-being.

When Barack Obama said "you didn't build that", he was speaking an important truth. Some people like Ms Mensch, however, are too knuckleheadly narcissistic to appreciate this.

June 16, 2014

Militarism and growth

There's one big omission in Tyler Cowen's argument that peace is bad for growth - opportunity cost.

The conventional neoclassical view is that £1 spent on the military is £1 not spent on something else, and that something else might well involve more productive activity than having soldiers sitting in barracks. This was the point made by Frederic Bastiat in his 1850 essay, That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen:

When a tax-payer gives his money either to a soldier in exchange for nothing, or to a worker in exchange for something, all the ultimate consequences of the circulation of this money are the same in the two cases; only, in the second case, the tax-payer receives something, in the former he receives nothing. The result is - a dead loss to the nation.

Against this, Tyler's arguments seem questionable. His claim that "the very possibility of war focuses the attention of governments on getting some basic decisions right" might surprise those of us who suspect government is dysfunctional even in matters of life and death; the phrase "snafu", remember, is military slang.

And whilst he is right to point to some innovations that arose from militarism, doing so runs into Bastiat's injunction to consider the unseen. From a neoclassical viewpoint, military spending diverts resources from cilivian spending, some of which would have produced other innovations. It's possible that a bigger civilian economy would generate faster growth by "learning by doing effects", or simply because the private sector is on average better at innovating than the government.

All of these objections, however, rest upon a questionable assumption - that resources are fully employed so that higher military spending means lower civilian spending. If resources are unemployed, the opportunity cost argument fails so Tyler might be right: for this reason, he is too hasty to dismiss Keynesian considerations.

In this context, Tyler has some interesting predecessors - Marxian underconsumptionists such as Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy. Back in 1966 they argued that capitalist economies tend to stagnate because capitalism's massive potential to produce was not matched by growth in potential demand. Military spending, they argued, helped fill this gap and thus boost growth:

If one assumes the permanence of monopoly capitalism, with its proved incapacity to make rational use for peaceful and humane ends of its enormous productive potential, one must decide whether one prefers the mass unemployment and hopelessness characteristic of the Great Depression or the relative job security and material well-being provided by the huge military budgets of the 1940s and 1950s. (Monopoly Capital, p210)

Keynesians might object that civilian public spending would also boost aggregate demand. But, said Baran and Sweezy, from a capitalist point of view military spending was superior. It gave fat, reliable profits to government contractors in a way that, say, paying teachers doesn't. And a militaristic society fosters a culture amenable to capitalists, of conformity to authority.

So, who's right - Tyler and the Marxian underconsumptionists or the neoclassicals? Personally, I think this is another area where there are no universal truths in economics. Militarism might well have been bad for economies in the full-employment late 60s and inflationary 70s. But it's plausible that it helped in the deflationary 30s. And it could be that today has more in common with the 30s than the late 60s.

June 15, 2014

Cognitive biases in football punditry

Football might be the world's most popular sport, but moaning about co-commentators runs it a close second: so far, Clarke Carlisle, Andy Townsend and Phil Neville have all trended on Twitter and not in a good way.

One reason - or at least justification - for this contumely is that their judgments are often clouded by numerous cognitive biases; I've long suspected that Daniel Kahneman could have re-written Thinking Fast and Slow by taking examples solely from football punditry.

Here is an (incomplete) inventory of these biases:

1. Hindsight bias. How often after a player shoots wide, does Andy Townsend say he could have passed instead? It's easy to know the right thing to do when you've seen what went wrong. This is especially true when discussing defences. Pointing out that the defensive shape was wrong after it conceded a goal is not good enough; the question is: did that same shape prevent many other goals? Americans call this Monday morning quarterbacking: it's a shame there's no English equivalent.

2. Outcome bias. Results shape our perceptions of performance. For example the Netherlands' 5-1 defeat of Spain looks like a tonking. But their third goal might have been disallowed; their fourth was due to an unusually bad goalkeeping error and their fifth caught a demoralized side on the break. It's a cliche - because it's true - that football is a game of small margins, but if those margins all drop in your favour you can achieve a great result without a proportionately superior performance.

3. Misperceiving randomness. There's always one team at a World Cup that does surprisingly well. This, though, is only to be expected. A lot of teams have a small but reasonable chance of getting to, say, the quarter-final. Across 32 teams, one of those chances is likely to turn up - just as we are likely to win a prize if we buy enough lottery tickets.

4. The hot-hand fallacy. This is a tendency to see "form" where none really exists but merely a run of luck. Take, for example, a player who scores a goal every other game - roughly Suarez's and van Persie's record but less that Dzeko's. Over a 50-game career, such a player has a 50-50 chance of scoring six goals in six games. Such a run could well be enough to win him a golden boot and legendary status. A variation of this fallacy is the "commentator's curse" - when a commentator praises a player only to see him shank a pass horribly. What happens in such cases is that an in-game run of luck suddenly stops.

5. Bayesian conservatism. Once we've got an idea that a team or player is rubbish, we interpret evidence to back up this idea; this is seen in co-commentators repeating themselves. My prior is that Diego Costa is a nasty cheating traitor who will therefore fit in well at Chelsea; I doubt this will change.

6. Selective perception. This is closely related to conservatism. It's our tendency to notice evidence that supports our priors more than evidence that contradicts it. So if we have an idea that someone is a good player, we'll spot his good points more than his bad; this is especially likely because so much of what players do (or don't do) happens when they don't have the ball; do they make good runs, or track back well?

7. Over-reaction. For example, Uruguay looked poor last night. Is this because they are a genuinely mediocre side (as their qualifying record suggests) or is it because they had an off-day? We can't tell for sure on the basis of 90 minutes. If we do so, we might well be over-reacting.

8. Overconfidence. Everyone thinks their opinions on football are the correct ones, in part because we underweight our vulnerablity to all of the above; this is the Dunning-Kruger effect. One example of this is that many of us are backing Brazil to win the cup. But in fact, although they are favourites the smart money thinks there's a 75% chance they won't win.

Of course, cognitive biases aren't necessarily wrong; indeed, they persist precisely because they sometimes (often) lead us to the right conclusion. And sometimes, they can cancel out; for example, Bayesian conservatism offsets over-reaction. My point is merely that one reason why pundits so often annoy us is that they are prone to such biases - and, of course, we are morely likely to see such biases in others than in ourselves.

June 14, 2014

Affluence, & art

Anyone who's spent much time within my earshot will know that I regard Jolie Holland as a genius. However, on seeing this I felt betrayed. She's having fun. With friends. The low-fi marginalized obscurantist I fell in love with has left me.

However, our instincts are something we must analyze. Why do I feel this way? In part, it's because I've lost my manic pixie dream girl. But there's something else going on.

It's that we expect our heroes to suffer. You don't have to look far in our cultural history to find the origin of this - though in the "song of the millennium" Jolie disavowed the analogy - but, curiously, the image of the crucified Christ was rare in the early centuries of Christianity.

This is especially true of cultural figures; the "tortured genius", the "27 club" and the artist starving in the garret are cliches.

However, we don't expect our doctors or - perish the thought - or bankers or manager to suffer for their craft, so why should we expect artists to do so, and be disappointed when they don't?

One answer is that suffering is necessary to express others' pain. But art isn't necessarily about suffering: think of, say, Austen or Armstrong. And I suspect there's a massive misperception of correlation going on here. Of the billions of people to have led lives of poverty and misery, only a tiny handful have produced great art. And of the tiny minority to have led relative comfortable lives, several have done so; even within jazz music - a genre stuffed with hard lives (some self-inflicted) - Miles Davis and Duke Ellington came from relatively affluent backgrounds.

You might think all this is far removed from my usual preoccupations. I'm not so sure (not that I care if it is). The Easterlin paradox poses the question: what are the benefits of economic growth? If it were the case that more widespread affluence were to deprive us of great art, then growth would indeed be a mixed blessing.

Sure, it might feel like this; one could easily argue that many musical forms in particular are in decline. But contemporaries are rarely good judges of culture - Beethoven and be-bop alike had bad reviews - and it's normal to think that the Golden Age was in the past.

So, perhaps our instincts are wrong. And even if we do live in an age of mediocrity, it might be for reasons other than our greater prosperity than earlier generations.

But what of Jolie's new album? I think the hivemind summarized by metacritic has it roughly right. If you're inviting comparisons with the Velvet Underground rather than Billie Holliday, you're not doing too badly.

June 12, 2014

Implementation

Larry Summers says something important and overlooked here: "it is much easier to design policy than to implement it."

This is surely true. It's a cliche of ministerial memoirs that a man arrives in Whitehall with high hopes only to find that reform is harder to achieve that he hoped. Take for example universal credit. Most of us would agree that it is a good idea in principle to simplify benefits and reduce withdrawal rates (let's leave aside the level of the benefit). However, the implementation of the scheme has proved trickier than the basic idea. A similar thing might be true of free schools and I suspect that in foreign policy - in peacetime and war - implementation is everything and top-level policy design relatively trivial.

However, media reporting of politics underweights this. Political reporting, and especially comment, dwells upon either soap opera or policy initiatives. Of course, there is much reporting of implementation but this is mostly after-the-fact descriptions of individual failure rather than analyses of the structures which produce that failure - which corroborates the old jibe that a journalists is someone who watches the battle from the mountaintop and then rides down and bayonets the wounded.

This is to be regretted because there are strong reasons to suspect that the policy implementation process is sub-optimal.

One is that politics is dominated by what I've called cargo-cult management. There's a fetish of "leadership" and "boldness" which encourages a neglect of the unglamorous gruntwork of proper management: tracking progress, achieving small partial targets and overcoming problems. This neglect will be magnified by cognitive biases such as overconfidence and groupthink.

Perhaps the most grievous problem, though, is a lack of information. "Make sure you get real-time, high-quality data" says the Cabinet Office Implementation Unit. Giles Wilkes' experience suggests this advice has, well, not been implemented:

Much of the time, Whitehall throngs with officials struggling just to find out what is going on. The sound of dysfunction is not the cacophony of argument, but the silence of suppressed documents and unreturned phone calls.

There are many reasons why this is the case. Some are exacerbated by politicians' own stupidity and arrogance; if they think bad news challenges their egotistical self-perceptions they'll be loath to hear it and underlings will censor themselves, and if whistleblowers are threatened with disciplinary action they'll keep quiet. Other problems, though, lie in the very nature of hierarchy. It easily produces silo mentalities and a lack of trust which impedes the information flow necessary for proper policy implementation. It also yields perverse incentives: it's much more pleasant to give your superiors good news than bad - so guess what they'll hear?

In saying all this I'm merely echoing something Kenneth Boulding wrote back in 1966 (pdf):

Organizational structure affects the flow of information, hence affects the information input into the decision-maker, hence affects his image of the future and his decisions, even perhaps his value function. There is a great deal of evidence that almost all organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

The questions he posed back then have not satisfactorily been solved. It is not just the England football team that has failed to progress since 1966.

June 11, 2014

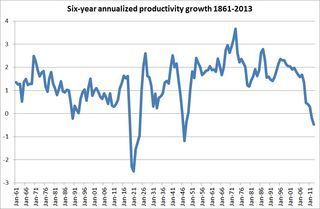

The productivity slump

Productivity growth is still falling. Today's statistics show that hours worked rose by 1.5% in the three months ending in April, but the NIESR estimates that GDP grew by only 1.1% in the period.

This is weird in two senses.

First, it means that productivity is now significantly lower than it was in 2007. Such a prolonged fall is almost unprecendented. My chart shows that, except for the transitions to peacetime after the two world wars, we haven't seen a six-year long fall in productivity since the late 1880s*.

Secondly, it gravely weakens the most optimistic explanation for the post-2008 drop in productivity. We had hoped that this was due in part to labour-hoarding; firms hung onto skilled workers in the downturn in anticipation of needing them in the recovery. This theory, though, implies that productivity should now be rising as output recovers and hoarded labour is utilized more intensively. That it is not doing so suggests that there's some other reason for the productivity slump.

But what? There are several possibilities, including a slowdown in technical progress (pdf) and the possibility that the fall in bank lending is retarding the "external restructuring" that usually contributes so much (pdf) to productivity growth.

Although the productivity slump - like so many other issues! - doesn't get much attention from the political class, it matters enormously for the cost of living crisis. If productivity is falling then real wages can rise only if there's a fall in the share of profits in GDP or if there's a favourable change in the terms of trade such that import prices fall. The former is unlikely given the power of capital. And the latter should not be banked upon, especially if Iraq's oil supply is disrupted.

This poses the question: what can be done to raise productivity?

One possibility is that we should simply wait. Maybe, as MacAfee and Brynjolfsson argue, we'll see productivity surge once managers reorganize production to take proper advantage of digital technology. Or maybe the recent pick-up in business optimism will encourage firms to invest in productivity improvements; as Christopher Gunn points out, animal spirits can cause productivity changes.

But what if waiting isn't enough? What policy changes might raise productivity?

There's one answer here that isn't sufficient - deregulation. The data shows that during the free market era (1855-1914) output per worker grew by 1.1% per year, compared to growth of 2.1% during the social democratic period 1946-79. This tells us that the idea that free markets generate big productivity rises owes more to bigotry theory than to historical experience.

* The data comes from the Bank of England, updated from ONS sources.

June 10, 2014

"British values"

Michael Gove's proposal that schools promote Britsh values prompts the obvious question: what are British values?

The standard politicians' answer is sanctimonious and hypocritical talk of toleration and fair play - presumably to distinguish us from the bigoted Dutch and cheating Belgians.

We can, though, tackle this question another way. A person's values consist not in what they say but in what they do. Actions speak louder than words. As that book which Gove sent to schools said:

Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?

Even so every good tree bringeth forth good fruit; but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit. (Matthew 7:16-17)

Fruits can be measured. To discover British values, we should therefore look at how our behaviour differs from that of other countries.

In many ways, it doesn't. For example, school results, openness to migration and life satisfaction aren't much different from other developed countries. One British value, then, is mediocrity. Here are some other values:

- Drunkenness. Brits consume an average of 10 litres of alcohol per year, compared to an OECD average of 9.1.

- Laziness. The average Brit works 1654 hours per year, compared to an OECD average of 1765, although we are around average for the productivity of those hours.

- Obesity. A higher proportion of Brits are porkers than most other nations.

- Criminality.The British are more likely (pdf) to rob, rape and assault people than are citizens of most other developed nations - though we're less inclined to commit murder.

It's not all bad, though. Brits are also relatively environmentally friendly. UK CO2 emissions per unit of GDP are one-third below those of the OECD average, although the latter is inflated by the US's high pollution. And we are also more generous to poorer nations; our overseas aid is a larger share of GDP than most other nations - though whether all Tories share this value is unclear.

There's one other big difference between us and many others - our acceptance of inequality. The top 1% get 12.9% of gross income in the UK. Though less than the US (19.3%), this is more than France, Sweden, Germany or Switzerland. Whether this value is to be applauded or not is debateable.

On balance, the empirical evidence suggests "British values" are not to be encouraged. But, then the facts are irrelevant, aren't they?

June 9, 2014

Why fix banks?

Do we need banks? Frances raises this question. She says:

Lack of spending in an economy (shortage of aggregate demand) is caused by distributional scarcity of money, not by lack of loans. It is not necessary to restore lending in order to encourage spending. It is necessary to replace the money that is not being created by banks.

She's right. The famous "helicopter drop" - more realistically, a money-financed fiscal expansion - might well* do more to boost aggregate demand than measures to boost credit supply such as the Funding for Lending Scheme or "targeted" LTROs.

But this poses the question. If governments can bypass banks by simply printing money, why bother to fix the banking system at all? Why not just let it be a dysfunctional casino?

The question gains force from the likelihood that, in practice, measures to improve bank lending are in effect subsidies to bankers. I suspect that the reason bank shares did so well after the ECB's announcement last week isn't so much that investors are looking forward to a brighter economic future, but simply that LTROs are yet more hand-outs.

There is, though, an answer here. It's not that helicopter money would be inflationary; in the euro area, higher inflation is something to be desired. Nor is it much of a problem that such a policy would create a merely "artificial" boom; I've always been irritated by Austrians' tendency to dismiss some economic actions as less genuine than others in violation of Hayek's justified warnings about the boundedness of individual knowledge.

Instead, the reason to fix the banks lies in allocative efficiency. One function of banks - albeit one they have always performed indifferently - isn't merely to create money but to screen investment projects, financing good ones and rejecting bad. A simple helicopter drop isn't sufficient to ensure that enough money flows to the businesses or potential businesses that need it.

You might object that it's silly to worry about allocational efficiency when the economy's depressed: as James Tobin said, "It takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap."

However, the inefficiency caused by inadequate bank lending isn't merely a static one. It matters for growth too. As Jonathan Haskel and colleagues have shown (pdf), a lot of productivity growth comes from "external restructuring" - from new establishments opening and older, inefficient ones closing. A lack of bank lending prevents this restructuring and so slows down productivity growth. I don't think it's an accident that UK productivity growth has slumped since the financial crisis.

In this sense, Frances isn't entirely correct. We do need to restore lending. How much we need to do so depends upon one's view of secular stagnation; if there's no demand for loans because there are no profitable investment opportunities, the need isn't as urgent as it would be if firms were credit-constrained**.

What would be nice, though, is if a way could be found to fix banks that wasn't simply a back-door subsidy. But it would be idealistic to hope for this.

* Subject to the caveat that some debt-constrained recipients of the money might use their windfall to pay down their debts.

** CBI surveys show that only a tiny fraction of manufacturers aren't investing because of a lack of external finance. I'm not sure how convincing this is. The CBI surveys only existing firms rather than those that don't exist but might if their would-be founders could get credit. And firms might be constrained from investing by the fear that credit might dry up in future even if it's available now.

June 6, 2014

The home-working puzzle

The internet isn't working. This is one inference we could draw from an ONS report this week. It shows that only 1.4 million employees, or 5.6% of the total, work from home*. This is a rise of only 1.5 percentage points since 1998.

This looks like a small rise given that we are supposed to have had a technological revolution since 1998, with broadband internet, Skypeing and mobile telephony making remote working much more feasible.

So, why hasn't homeworking increased more?

Of course, for many jobs it's just infeasible; you can't stack shelves at Tesco from home. And some people claim that we are more productive if surrounded by inspiring colleagues whom we can bounce ideas off, though in my experience this is...

But on the other hand, there are huge costs to working away from home: renting office space, transport costs and the waste of time spent travelling - and this is not to mention the stress and unhappiness of commuting.

Why, then, are employers still keen to incur these costs? There are two possibilities.

One is suggested by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson in The Second Machine Age. They point out that when electricity was introduced into American factories in the 1890s, productivity growth didn't initially change even though electricity was to revolutionize the economy. The reason for this, they say, is that "general purpose technologies need complements" - and the most important of these are changes in organization and business processes. But, they say, it was only after 30 years - when managers brought up on the pre-electricity era retired to be replaced by younger ones - that such changes were made to take full advantage of electricity.

It could be that a similar thing is retarding home-working: bosses accustomed to seeing their lackeys in the office aren't willing or able to make the organizational changes that would exploit new technologies.

There is, though, an alternative theory, associated with Stephen Marglin (pdf). He argues that the early factories supplanted home-working not because they were technically more efficient, but because they gave capitalists more control over the labour process and hence the power to extract more of the gains from the employment relationship for themselves. A similar thing might explain employers' aversion to home-working today. Or, more loosely, perhaps narcissistic managers want to feel a sense of power from seeing employees working.

What's consistent with this view - though not proof of it - is that the ONS finds that workers in higher-paid occupations such as technicians and managers are disproportionately likely to work from home. Some of us have the bargaining power to demand that we work in more pleasant conditions.

I don't know which of these theories is right. Luckily, though, the fact that I work from home has probably improved my health sufficiently to increase my chances of living long enough to find out.

* defined as spending more than half one's working time at home.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers