Chris Dillow's Blog, page 125

April 30, 2014

Begging the inequality question

Tim Worstall says Labour's idea of predistribution is inefficient because it is "cocking up markets". However, Labour defends predistribution - for example the freeze on energy prices - by claiming that markets are broken already. If they're right, such a freeze might be efficient in second-best terms.

What Tim's doing here is - literally - begging the question. He's assuming what must be proved - that we have an tolerably well-working market, intervention in which would be inefficient.

This, though, seems to me to quite a common error on the right. For example, Garrett Jones says we should become more tolerant of inequality, and less covetous. What this misses is that many of us dislike inequality not because we envy the mega-rich but because it is (sometimes) a symptom of malfunctioning markets - that, as Scott says, "the system is rigged." The fact that so many bosses get paid millions even for failure suggests that they are not paid their marginal product. Instead, some mix of agency failure, efficient wage considerations (bosses must be paid not to steal corporate assets) and arms races force pay above marginal product.

Sure, you can write models in which inequality emerges as if it were the product of free choices in a free market economy. You can also model a man's empty house as if he had called in the removal men - but if he has in fact been burgled, your models miss something.

I fear that some free market advocates - not all by any means, but some - are mistaking the map for the terrain. They forget that the textbook perfect competition model is not a description of reality but rather of a utopia against which to assess actually-existing markets. And sometimes - not always but in some important respects - they fall well short.

You might reply that this error is not a common one. Maybe not. But it could be a costly one. Insofar as advocates of free markets such as Garrett and Tim also defend inequality, there's a danger that the case for free markets gets poisoned by its association with indefensible inequalities.

My view of a free market economy is much the same as Gandhi's of western civilization: it would be a good idea.

A clarification. Of course, a free market economy would and does generate inequality. But most of us are more relaxed about J.K Rowling or Cristiano Ronaldo's wealth than about Dick Fuld's or Bob Diamond's. Free market inequality raises different issues than actually-existing inequality.

April 29, 2014

On economics education

What can economics students reasonably be expected to learn? Reading this post by Tony raised this question.

To see what I mean, consider the general skills one would need to understand panics and crashes, to take Tony's case. We'd need to know some maths and stats: what's wrong with Gaussian copulas? How do nonlinear differential equations describe bubbles? We'd need some economic history: without this, our only datapoint is 2008. We'd need detailed knowledge of regulation and market structure: what the heck is a CDO? To what extent did poor regulation cause the crisis? And we'd need some knowledge of the psychology of herding and wishful thinking, as well perhaps as some experimental economics: I'd add this paper to Tony's already-daunting reading list.

I'd be mightily impressed if a 40-year-old had all these skills. It would be utterly unrealistic to expect a 20-year-old to have them. And this is only one course.

The point here is that even the best undergraduate education can only scratch the surface of the discipline. It is therefore inevitable that students and their employers will complain about them being imperfectly prepared; as Cameron points out, such complaints are decades old. This isn't (just?) because their teachers are poor or ideologically blinkered. It's because three years is not long enough to learn very much.

So, what should economics students learn? I'd suggest that the priority should be to prepare them for lifelong learning about economics.

This should include a good grounding in conventional economics and - yes - in the mathematics required to understand it. This is necessary on practical grounds - for students going onto formal graduate study - but also intellectual ones. This is because conventional economics contains lots of truth. For example, the efficient market hypothesis gets tons of abuse, but the fact is that most stock market investors would be better off if they acted as if it were true. Also, you've got to understand conventional economics if you are to understand why and when it's wrong. I remember Manchester's Terry Peach telling me that heterodox economists must be better economists than neoclassical ones for precisely this reason.

However, learning only plain neoclassical economics isn't enough. It's like going to the gym and working only on your biceps; you'll end up a freak - albeit one capable of punching someone's lights out when they point this out. Something else is needed. That something isn't just heterodox economics, but a grounding in both statistical methods and critical thinking. By statistical methods, I don't mean deriving and proving lemmas about maximum likelihood estimators; if something's been proved once it doesn't need proving again. Instead, I mean knowing how to run statistical tests, how to interpret their results and the strengths and limitations of various statistical methods. Simon is right to say that the question "do fiscal expansions work?" should not have the answer "it all depends on whether you are a Keynesian or an Austrian." But it should lead to the question: what counts as good evidence here?

(My suspicion is that quite a bit of marginalist theory wouldn't survive a confrontation with the empirical evidence - but that's another story).

And it's here that behavioural economics enters. The point about cognitive biases is that they don't just apply to other people, but to ourselves. In this sense, learning about them should be a big part of a course on how to think properly.

The problem here is that there is a trade-off between depth and breadth; learning some things requires not learning others. But you'd expect the economics profession to be capable of dealing with trade-offs. Wouldn't you?

April 28, 2014

Interest rates, inflation & mechanisms

Reading Noah's discussion of the neo-Fisherite rebellion - the idea that low interest rates lead to lower inflation and higher rates to higher inflation - I heard the voice of the greatly-missed Andrew Glyn. He would ask: what's the mechanism? How, exactly, might interest rates have such an apparently perverse effect?

Let's start with the process whereby higher rates are meant to reduce inflation. The idea here is that they depress demand, thus opening up an output gap (or raising unemployment for those who prefer observable entities), which in turn reduces inflation.

However one big fact suggests that, in the UK at least, this mechanism is questionable. It's that the correlation between unemployment and inflation in the subsequent 12 months has been positive. Higher unemployment has led to higher inflation, not lower.

This is consistent with - though far from proof of - the possibility that higher interest rates do not lead to lower inflation. One reason for this might be that higher real interest rates act like an adverse supply shock. They not only reduce demand, but also tend to raise prices. I'm thinking of three possibilities here.

One was discussed by Fitoussi and Phelps (pdf) in their analysis of Europe's stagflation of the 1980s. Higher real rates, they say, encourage firms to increase their mark-ups to raise immediate cash rather than pursue growth. This is consistent with Rotemberg and Saloner's discussion (pdf) of why price wars are more likely in booms than slumps.

A second is that higher interest rates, especially if associated with less bank lending, tend to deter new companies from starting up or from expanding. This reduces the external restructuring that is a major source (pdf) of productivity growth, which would tend to add to costs.

The third is simply that interest rates are a cost of production - simply because production takes time and inventories, and higher rates raise the cost of both. (Let's ignore reswitching!)

Through these mechanisms, it's possible that higher interest rates act like higher oil prices or other costs of production. They both create unemployment and raise inflation. They raise the Nairu. Equally, lower rates - at least if associated with more plentiful credit - reduce both unemployment and inflation.

Now, there's an obvious objection to this. If lower rates lead to lower inflation why did Thatcher and Volcker raise rates in the late 70s and early 80s in order to (successfully) reduce inflation?

Here's a possibility. It depends on whether recessions have a "cleansing" effect. If they kill off lame ducks and allow productive firms to grow, their effect will be to reduce inflation. If, however, there's no such cleansing effect, they won't. And of course, whether there is (pdf) or isn't (pdf) might well vary from one recession to another.

In this sense, the question "do lower interest rates lead to lower inflation?" might have the answer: "sometimes yes, sometimes no." Maybe the reality is messier than models claim.

April 27, 2014

The problem of distribution

In a comment here, Nuno Ornelas Martins says: "the central problem of economics is the distribution of the surplus rather than the allocation of scarce resources."

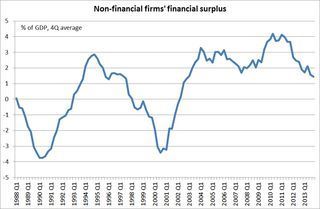

This, of course, flatly contradicts the standard view that scarcity is the problem of economics. However, in one context at least, he is right. J.W. Mason points out that, in the US, companies have (net) long ceased to raise money from financial markets. A similar thing is true in the UK; for years, companies' retained profits have exceeded capital spending - something which the OBR expects to continue.

It used to be the case that finance was scarce. The purpose of the joint-stock company was to overcome this problem, by allowing firms to raise small amounts of money from many dispersed investors.

But this is no longer so. From the point of view of existing companies, finance is abundant. Their problem is no longer one of the scarcity of finance, but instead of the distribution of surplus.

Sure, shareholder-owned firms raise cash. But they do so either through borrowing to buy back shares, or as a way for owners to cash out through IPOs. Such cash raisings aren't a means of raising investment funds.

This brings into question the nature of the firm. If external shareholders aren't necessary for raising investment funds, what use are they?

They don't provide effective oversight of managers; we know this from the theory of collective action and from the bitter experience of the banking crisis.

Nor is it that share prices signal which firms should invest and which shouldn't. Charles Lee and Salman Arif point out that, around the world, high investment leads to falling share prices, more earnings disappointments and weaker macroeconomic growth. This suggests that capitalism does a bad job of investment appraisal, with investment being driven by sentiment rather than by an accurate assessment of genuine profit opportunities. (Though this might tell us more about humans' bounded rationality than about the failure of capitalism.)

All this raises the question: if the problem is now the distribution of surplus, are capitalist institutions the best solution? It's tempting to think not. A natural alternative would be a more equal distribution of ownership, perhaps through a form of Roemerian market socialism, such that dividends would, in effect, be part of a citizens' basic income.

The obvious objection to this is simply that such a reallocation of property rights would be unjust; why should someone who owns lots of shares be expropriated more than one who is (say) long of housing?

And this raises a possibility which is counter-intuitive but I think at least reasonable - that the case for capitalism (in the narrow sense I intend here) lies more in justice than efficiency.

Note for the hard of thinking: I am not saying here that the central problem of economics is always distribution rather than scarcity. I'm just saying that, in this context and now, it is. Most interesting facts in the social sciences are local and particular.

April 24, 2014

Inequality: a missing perspective

The debate about inequality comprises, to a large extent, two camps. In one there are those like Martin Wolf who believe inequality is a problem which can be solved. In the other are those who doubt that inequality is a problem - either because "material equality has no intrinsic value" or because, as Tyler says, "what might appear to be static blocks of wealth have done a great deal to boost dynamic productivity."

This division, though, overlooks what seems to me a reasonably tenable position, which goes something like this:

Yes, inequality is a problem. This is partly because it is often a sign of market failure - as in banks' "too big to fail" subsidies or in an agency failure in CEO pay. But it also threatens to undermine democracy, social harmony and equality of respect.

However, sometimes, the solution is more costly than the problem. And inequality might be one of these times. There might be some efficient ways of reducing inequality - such as land value taxes, stronger trades unions or more worker ownership - but these lie outside the Overton window. Pretty much the only means of reducing inequality that is on the agenda is higher income tax. And in a country where tax morale is already low, higher taxes might have disincentive effects; they deter entrepreneurship as well as rent-seeking. What's more high taxes might cause what Assar Lindbeck calls (pdf) "norm drift"; in the long-run they might undermine pro-work and pro-entrepreneurship attitudes; this possibiliy is not captured by the IMF's finding (pdf) that moderate redistribution doesn't hurt near-term growth.There might be a good reason why to tax rates have fallen around the world since the 70s.

What's more, we can do a lot to help the worst off without worrying about the 1%. A citizens' basic income, serious job guarantee programme and better fiscal policy can be implemented whether we do something or not about the 1%. Indeed, given the political power of the mega-rich, social democrats might have more chance of success if they don't poke that particular hornet's nest.

Now, I don't believe this myself; I suspect it takes too pessimistic a view about Laffer curves. But it seems to me a position which reasonable people might take; it's close to Blairism.

This poses the question: why is it so little heard? It could be because it gets drowned out by the tribalism of the inequality debate; it breaks the first rule of political writing because it tells both sides of the debate they don't want to hear.

But there might be another reason. The weakness of this view might be related to what I've called the death of conservatism - the demise of the Oakeshottian melancholy tendency which sees some problems as insoluble, and its replacement with a managerialist faith that problems can be "addressed" as soon as we see them as such.

Personally, I find the loss of such a disposition a matter of regret, as it impoverishes our political debate.

April 23, 2014

Moyes' message

Some (female) tweeters have expressed exasperation at the amount of coverage given to David Moyes' sacking. I'm not sure they're right. Football is about more than 22 men chasing a ball. It also lets in light upon what is normally a shadowy but key feature of capitalist inequality - the role of management. So, in the spirit that every news item demonstrates what I've known all along, here are five lessons of Moyes' tenure at Manyoo.

1. "Nobody knows anything." There's a parallel between David Moyes and Gordon Brown. Both were widely seen at the time of their appointments as good successors to successful longserving leaders, and in both cases that widespread opinion was subsequently revised. (Contrast the reaction to Moyes' appointment to the "Arsene who?" headlines when Wenger became Arsenal boss.) This suggests that identifying successful leaders is like venture capital and the movie business: "nobody knows anything." As Marko Tervio has shown, this fact alone can generate inequality, because hirers will prefer to pay over the odds for known mediocrities rather than take a risk on unproven geniuses.

2.The contrast effect matters. Objectively, David Moyes' record at Manyoo wasn't too bad - especially if, as Danny Finkelstein stresses (£), we take account of the statistical noise surrounding such a small sample of results.But it looks bad because of the contrast with his predecessor's record. The message, as Andrew Hill says, is: "Never, ever, agree to take over from a legend."

3. Organizations matter more than individuals. The truth is that the Manyoo team isn't very good. Only three or four of them (Rooney, Mata, Van Persie and De Gea) would get into the first 11 of a top four side, and they won the league last season because their rivals were in transition rather than because of their own brilliance. Danny's right to say: "In most cases it is impossible to separate the success of a business leader from that of his or her team, from market conditions and from the strength of the product." Or as Warren Buffett put it: "when a boss with a good reputation takes over a business with a bad one, it is the business that keeps its reputation."

4. Competitive advantage is fleeting. Manyoo lost theirs because their rivals improved - in most cases by spending a lot of money. What's true in football is true in business generally - albeit at a slower pace thanks to market imperfections. Even giants die eventually.

5. Matches matter.Everybody has strengths and weaknesses, not least because a weakness is just a strength redescribed*. Moyes' misfortune is that his weaknesses - tactical caution and an inability to manage egos - proved more damaging than expected. This suggests that the job of finding a new manager is often misdescribed. The trick is not to find the best man but rather to find the right match - the man whose weaknesses won't hurt the organization too much.

There is, I think, a common theme here. It's that our attitudes to business leaders are coloured by cognitive biases and a failure to acknowledge bounded knowledge. Such attitudes might do more to sustain inequality than they do to promote effective organizations.

* For example, boldness is recklessness, attention to detail is pedantry, consistency is inflexibility and so on.

April 22, 2014

"British workers hit hard"

There's one curious thing about Ukip's notorious posters that hasn't been mentioned - that they represent a flat rejection of orthodox neoclassical economics.

"British workers are hit hard by unlimited cheap labour" says one poster. However, in theory this would be true even if our borders were completely shut to foreign workers.

The idea here is simple. If there were unlimited cheap labour overseas, foreign companies would be able to produce very cheap goods which would undercut UK firms. Those firms would then either close down - which would raise unemployment and cut UK wages - or would force their workers to accept lower wages. Either way, some British workers would be "hit hard." This would happen so long as there is free trade, even without immigration. This is factor price equalization, which is a cornerstone of basic trade theory.

In pretending that British workers can be protected from cheap foreign labour by immigration controls alone, Ukip is therefore rejecting factor price equalization.

Now, to some extent it is right to do so. FPE doesn't hold precisely*. But there is some truth in it: it's no accident that the relative labour market conditions of unskilled workers in the west have deteriorated since the entry of China and India into the world economy.

Nevertheless, this poses two questions for Ukip. One is: if unlimited cheap foreign labour is kept out of Britain, what do you suppose it will do? Many of the answers involve threatening UK wages via trade rather than via immigration.

The second is: if you're rejecting basic economics in one big regard, why are you so keen to accept it in others? Just as it's too simplistic to say that FPE holds completely, so it's also too simplistic to say that immigrant labour greatly bids down domestic wages: immigrants are complements to British workers as well as substitutes, and even if wages are bid down, the consequent disinflationary pressures should allow the Bank of England to run a looser monetary policy thus providing a boost to the demand for labour.

Ukip, then, seems to be rather selective in its faith in basic economics. Call me Mr Cynic, but I suspect that such selectivity might not be entirely based in empirical evidence.

* In this context - yet again - there's a useful distinction between mechanisms and models. As a precise model of the world, FPE is inadequate. But as a mechanism/tendency it contains some truth.

April 20, 2014

12 alternative principles

An old speech by Tom Sargent has had some praise and some criticism. But what would a more heterodox list of 12 economic principles look like? Here's my effort, observing Sargent's constraints of concision and relevance for young people starting out in life:

1. People have different motivations: wealth, power, pride, job satisfaction and so on. Incentive structures which suit one set of motives might not work for another.

2. Many things are true but not very significantly so.

3. Power matters: conventional economics under-states this.

4. Luck matters. The R-squareds in Mincer equations are generally low.

5. There is a great deal of ruin in a nation, and in an organization.

6. Individual rationality sometimes produces outcomes which are socially optimal as in Adam Smith's invisible hand, and sometimes not.

7. Trade-offs between values are more common than politicians pretend, but are not ubiquitous.

8. Cognitive biases are everywhere.

9. Everything matters at the margin, but the margin might not be very extensive.

10. The social sciences are all about mechanisms. The question is: which ones work when and where? This means there are few if any universal laws in the social sciences; context matters.

11. Accurate economic forecasting is impossible. But time-varying risk premia might give us a little predictability.

12. Risk comes in many types. Reducing one type of it often means increasing exposure to another type.

April 19, 2014

Axelrod & matches

Whilst I was gardening this morning, I wondered whether Labour is right to spend big money hiring David Axelrod as a campaign advisor.

The question arises because in gardening, context matters. The point isn't simply to find good plants, but to put the right plant in the right place: Japanese laurels at the back of a shady border, lupins in sheltered sunny spots and so on.

Exactly the same is true for people. Very often, successful hires depend not just upon the qualities of the hireling, but the match between him and context: what matters is putting square pegs into square holes.When the match is right, individuals look like great workers and when it's wrong they look like duffers even though they are the same people. For example:

- Tony Pulis struggled to turn Stoke from a team of mediocre cloggers but has done well in saving Palace from relegation.

- Christine Bleakley and Adrian Chiles looked like successful, popular presenters when they were on the One Show, but lost a big audience when they joined ITV's Daybreak.

- Boris Groysberg has shown that "star" equity analysts often see their abilities deteriorate when they move job. "Exceptional performance was more context-dependent than is explicitly recognnized by star performers or their employers" he says.

- Firms who hire managers from General Electric see very variable (pdf) results, depending upon whether the manager's experience is a fit with the organization or not.

- The performance of the same cardiac surgeons varies according to which hospital they work at. "surgeon performance is not fully portable across hospitals" conclude (pdf) researchers at Harvard Business School.

The question, then, is not: is Axelrod a clever chap? It's: is his successful experience with the Obama campaign portable or not? And there are reasons to fear not: UK elections are less fought upon attack campaigns and TV adverts than US ones. Outside of the US context - for example in his attempts to help Mario Monti - Axelrod's record is not stellar.

And herein lies my concern. I fear this hire is another example of cargo cult management - performing the ritual of hiring a star without inquiring closely into whether the star has the right context in which to succeed.

In this sense, Miliband seems still to believe in one of the most noxious aspects of New Labour ideology - a belief that organizations can succeed if only great men can provide "leadership." Such an ideology doesn't just help sustain inequality. It is also empiricially dubious.

April 17, 2014

Income & gender equality

Sometimes, it's the little words that reveal so much. I was struck by Phil's response to Rashida Manjoo's claim that sexism is worse in the UK than elsewhere. He writes:

I didn't for one moment think that the UK's sexism problem was worse than other developed nations.

Hold on. What's that word "developed" doing here? Why judge the UK only by comparably rich nations? Is Phil presuming that sexism is worse in poorer nations?

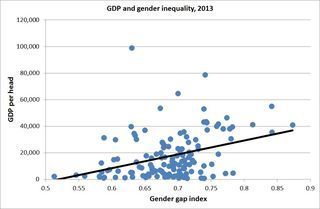

If he is, he's right - up to a point. My chart plots gender inequality, as measured by the WEF's gender gap, against GDP per head. You can see that there's a positive correlation in the chart; it is 0.36 for all 134 countries, but 0.52 if we exclude middle east countries who tend to have high oil revenues and poor gender equality scores. Sure, some poor countries score well for gender equality - such as Mozambique or the Philippines - but generally, Phil's presumption is correct. Poor countries are generally sexist ones.

The evidence here, of course, isn't just cross-sectional. It also exists in time-series; western economies are much richer than they were 100 years ago, and gender equality has also improved in this time; women at least have the vote now.

Why is there this correlation? There are three possibilities:

- Gender equality actually promotes economic development. There's good evidence (pdf) that educating girls (pdf) has a high pay-off in poor countries, perhaps by enabling them to better control fertility (pdf) and child mortality. And one study has found that "countries with higher shares of women in parliament have had faster growing economies" - probably because large numbers of female parliamentarians are a sign of other enlightened policies.

- Poverty and gender inequality have a common, third, cause. If men are wedded to traditional ways of treating women, they are likely also to be disposed to other traditional ways of life which are hostile to development.

- Development creates equality. As Ben Friedman and Deirdre McCloskey have shown, richer people tend to be more civilized ones. Yes, western bankers and CEOs are bastards, but they're vastly better than the Lord's Resistance Army or Boko Haram.

I draw two inferences from this. One is to support a point made by Diane Coyle in GDP: A brief but affectionate history. She says that although GDP is not a meaure of welfare, it is "highly correlated with things that definitely do affect our well-being." It would be rash to assume that none of the correlation between gender equality and income was due to causality from income to equality. Maybe one reason we need growth, especially in poorer countries without oil, is to improve the odds for women.

Secondly, there's a question here. The evidence shows that prosperity and gender equality go together. So why shouldn't this be true for other forms of equality? Why are women so unusual?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers