Chris Dillow's Blog, page 124

May 25, 2014

The Overton wall

There's a common implicit theme in two of my recent posts which I should make explicit. It's that conventional party politics, and discussion thereof, systematically excludes some important questions. The Overton window - the narrow range of subjects which are deemed fit for discussion - is surrounded by an Overton wall, which blocks lots of important questions.

I posed one such unasked question here: why should the public's preferences shape policy, when those preferences are ill-informed or downright malevolent? The answer is not that, in a democracy, public opinion must rule. There are huge areas of social life where democracy is withheld - namely in companies - even though workers' opinions on how to organize their workplaces are probably better-informed than their opinions on, say, immigration. But the question: "when should democracy exist and when shouldn't it?" is off the party-political agenda.

So too is the question I posed here: could it be that there are tighter limits upon the ability of governments to redistribute incomes or raise growth than politicians - especially social democratic ones - pretend.

Other questions are also under-emphasized, for example:

- Are secular stagnation and/or technical change a threat to people's living standards and if so what can be done? (Yes, Osborne at least showed awareness of the debate about stagnation, but his flat denial of its likelihood was both unconvincing and ignorant of the fact that policy should address not just central case scenarios but also risks, especially if these are low probability but high-cost ones).

- How should fiscal policy be set if - as I argue on p12 of this pdf - economic forecasting is impossible?

- Whilst politicians had an opinion on whether Pfizer should have taken over Astrazeneca, none seemed to pose the more fundamental question: are shareholder-owned companies with (perhaps) short-term horizons really a good way of organizing research with payoffs in the far-distant future?

Now, you might object that I'm guilty here of standard commentator's narcissism: "everyone is wrong because they are ignoring my hobby-horse". I don't think so. These issues are increasingly being discussed in the economic mainstream; when Charlie Bean says Bank rate might stabilize at 3%, he's hinting at the possibility of prolonged stagnation. And they surely direct address the important issue of people's living standards.

What's more, because they are not asked, we are left with an absurd politics which seem to think that jobs and incomes are threatened only by immigration rather than by technical change, globalization or capitalists' power, and which gives us a cult of leadership which thinks that a party's fortunes can be tranformed by changes of leadership.

It's often said that people are estranged from a political elite which is dominated by Oxford PPEists. What this misses is that some of us who are Oxford PPEists also find party politics irrelevant and alienating.

May 24, 2014

Housing vs financial wealth

Chris Giles deserves great credit for his careful scrutiny of Thomas Piketty's data, and Piketty also deserves credit for the openness of that data and for his generous response to Chris. Like Justin Wolfers and Paul Krugman, though, I wonder just how damaging Chris's critique is of Piketty's central thesis.

Chris says that, in the UK, "there seems to be little consistent evidence of any upward trend in wealth inequality of the top 1 percent." He points to ONS data showing that the top 1% owned 12.5% of all wealth in 2010-12.

However, this proportion is depressed because house prices are high. These mean that the owner of quite a modest home has substantial wealth which naturally depresses the proportion of wealth held by the really well-off.

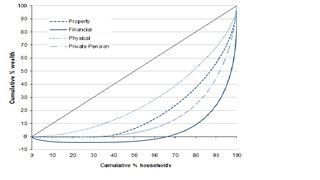

If we look only at financial wealth, we see a different picture. The top 1% owns 36.4% of all financial wealth, and the top 10% owns 75.9% (table 2.6b of this Excel file). As the ONS points out, the Lorenz curve for financial wealth is much steeper than that for property wealth. If you believe the ONS is under-counting offshore wealth, inequality is even greater.

This poses the question: should we conflate housing and financial wealth as Chris and Thomas both do? Perhaps not, because housing wealth might not have as much "wealthiness" as financial wealth, in four senses:

1. Is housing net wealth at all? Willem Buiter argued that it isn't, because high house prices are a liability for non-owners who'd like to buy. On this view, the liabilities of non-owners are greater than the ONS estimates and so wealth is more concentrated than it claims.

Housing is only wealth for those planning on trading down - and these are probably a minority of home-owners.

2. Does housing do as good a job as financial wealth in cushioning us from shocks? There are two reasons to think not. One is that housing wealth doesn't protect us from local economic risks. If a big local employer closes down, home-owners might lose their job and see their house price fall. Also, housing doesn't protect us from distribution (pdf) risk. Think of house prices as being capitalized future wage earnings and share prices as capitalized future profits. If there is a permament(ish) shift in income from wages to profits - say because of robotization, globalization (pdf) or other increases in capitalist power - house prices will fall as wages do but share prices will rise. Financial wealth will therefore be a better hedge than housing against a drop in wages.

3.Does housing wealth give us as much freedom as financial wealth? I suspect not, in part because it's lumpier than financial wealth: it's easy to create an income by drawing down financial wealth, but less easy to draw down housing wealth as home equity release schemes are often poor value.

4. Does housing give us political power? To some extent, yes; nimbyism prevents new building, and there's a strong lobby in favour of low mortgage rates (though its power consists in harming the incomes of moderately well-off savers rather than the mega-rich with more diversified portfolios). But on the other hand, it is ownership and/or control of capital that confers power over economic policy-making, for example by being able to demand low taxes or that governments don't damage business "confidence".

My point here is a simple one. Wealth inequality matters because of what wealth does. (For me, one curious omission of Piketty's book is that he doesn't tell us enough about why we should care about inequality.) It's possible that financial wealth does more than housing wealth. If so, it is inequality of this that is more important.

May 23, 2014

Immigration: the preference problem

What role should the public's preferences play in policy formation? I'm prompted to ask by David Goodhart:

The [immigration] debate is over. About 75 per cent of the public think immigration is too high and should be reduced. All three main parties agree.

But of course, whilst public opinion might be settled on one side of the question, most (pdf) expert opinion (pdf)lies on the other side. By "experts" I don't just mean pointy-headed "metropolitan" intellectuals such as Jonathan Portes, but also those members of the public with most experience of immigration. UKIP have polled badly in Birmingham and London which have for years received many immigrants. This is consistent with a finding by Mori (pdf), that whilst most people think immigration is a national problem, they don't believe it to be one in their own area. As Robert Peston says:

The threat to living standards and quality of life of immigration is more in the perception than the reality.

In saying this, I don't mean to imply that all opposition to immigration is wrong. The problem is that reasonable disquiet about immigration - a sense of loss of feelings of home - are commingled with ideas that are mistaken (for example on the economics of migration), illiberal and yes occasionally racist.

Hence my question: why should politicians accede to preferences that are misguided or even evil?

There's a long intellectual tradition which says they shouldn't - from Edmund Burke contending that MPs should over-ride the "hasty opinion" of their constituents, through Jon Elster (pdf) and Eric Posner (pdf) (among many others) to Daniel Hausmann arguing that:

people's preferences are in some circumstances good evidence of what will benefit them. {But] when those circumstances do not obtain and preferences are not good evidence of welfare, there is little reason to satisfy preferences.

This is, of course, no mere theory. Human rights exist precisely to protect people from the illiberal preferences of majorities, and politicians have often over-ridden public opinion - for example in opposing the death penality.

The question then is: is immigration policy an area where the public's preferences should be fulfilled or not? The last Labour government thought not, and (haphazardly) prioritized liberty and economic efficiency over the majority will.

The problem here, of course, is that whilst the role that preferences should play in policy-making and in welfare is a tricky philosophical one, politicians are in the business of seeking power rather than higher ideals. The pressures on them are thus to kow-tow to populism. We should remember, though, that from many perspectives there can and should be more to politics than this. In this sense, Goodhart is wrong: the debate certainly isn't over.

May 22, 2014

What can governments do?

Do we greatly over-estimate what governments can accomplish? This question occured to me during my holiday reading. This is because there's a common theme in Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century and in Greg Clark's The Son Also Rises. Although the two books discuss very different types of inequality - wealth in Piketty and opportunity in Clark - they share the same view that inequality is hard to change. Here's Clark:

The intergenerational correlation in all the societies for which we construct surname estimates...is between 0.7 and 0.9, much higher than conventionally estimated...The arrival of free public education in the late 19th century and the reduction in nepotism in government, education and private firms have not increased social mobility.

And here's Piketty:

France remained the same society, with the same basic structure of inequality, from the Ancien Regime to the Third Republic, despite the vast economic and political changes that took place in the interim.

Reading this reminded me of Landon-Lane and Robertson's paper, in which they argued that "there are few, if any, feasible policies available that have a significant effect on long run growth rates"

If we put all three claims together, we have a contention that should disturb leftists especially - that there is little that governments can do to radically improve the life-chances of the worst off, because there's no (feasible?) way of greatly increasing growth or of greatly increasing the redistribution of wealth or opportunity*.

I stress the words "greatly" and "radically" in that paragraph; it's quite possible that a government can nibble away at the edges of inequality, and this is not to be sniffed at. The point is merely that there might be powerful reasons why Labour governments have generally disappointed their supporters.

In this context, I suspect there has long been an excessive division on the left, the latter-day manifestation of which is between Blairites and the far left. On the one hand are those who are too happy to compromise with capital, and on the other are those who are over-optimistic about the prospects for radical change. There is, though, a third way: we can recognise that governments can only do a little to help the worst off, whilst at the same time deploring this fact and regretting the power that capital has.

In saying this, I do not intend to endorse Gramsci's phrase about “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”. This has long struck me as silly: willing things don't make them so.

* I'm using "feasible" ambiguously here. Infeasible might mean that policies won't work technically, or (as I suspect instead) that they are ruled out by the power of the rich.

May 8, 2014

What can economics explain?

The death of Gary Becker, the father of the "economics of everything" set me wondering: could it be that basic neoclassical economics does a better job of explaining "non-economic" behaviour than it does of economic phenomena?

Take three examples where basic neoclassical is, at best, questionable:

- A theory of distribution. The idea that wages are equal to workers' marginal product is deeply questionable. It seems instead that power, rent-seeking and institutional frameworks also matter enormously; the fact that there's no correlation between patterns of income inequality and of human capital inequality should be awkward for neoclassicals. And the idea of a marginal product of capital is just close to meaningless, which gives neoclassical economics little idea of where profits come from.

- The Solow-Swan growth model found that most economic growth was due to exogenous technical progress, which is pretty much no explanation of growth at all. The difficulty (pdf) of relating growth to human capital suggests that augmented theories do little better. And the fact that governments in developed economies can do little to change long-term growth rates suggests that growth theory hasn't (yet?) had a useful policy influence.

- The neoclassical explanation of unemployment stresses wage inflexibility and "rigidities". But this fails to account for why unemployment was high in the 19th century.

By contrast, Beckerian economics has given us some useful insights into crime, family life (pdf) and racial discrimination.

There might be good reasons for this difference. Matters of individual choice are often more tractable in the "non-economic" than economic arena. The man thinking of committing a crime, for example, doesn't face such severely bounded rationality and knowledge as the company boss making investment decisions. Problems of aggregating different goods are less relevant. And whereas financial capital is now abundant, time is not - and so the neoclassical presumption of scarcity remains relevant to our life choices.

Now, I'm not saying here that neoclassical economics of everything is a complete theory. The assumption of an atomic rational maximizer is challenged by cognitive biases and peer pressures - though Becker was well aware (pdf) of the latter. And it's an open question how far the Beckerian approach can explain the collapse in crime rates recently. It might be, though, that neoclassicals' limitations in these areas are more resolvable than in others.

What I'm saying here might earn me the wrath of both heterodox and orthodox economists, but it is in a sense trivial.Different theories can explain different things. The idea that one theory fits all owes more to fanaticism and tribalism than to the data.

May 7, 2014

Austerity, & the peak-end rule

There's more wisdom in Simon Wren-Lewis's casual comments than there is in many people's considered thoughts. Discussing the "absurd" idea that the recovery validates fiscal austerity, he says: "Next time you get a cold, celebrate, because you will feel good when it is over!"

Such celebration is a common psychological phenomenon. When I used to get attacks of gout, I would feel euphoric as they faded away because mere discomfort felt wonderful after extreme pain.

However, this euphoria can distort our judgments. Daniel Kahneman has pointed out (pdf) that our memory of painful experiences follows what he calls a "peak-end rule"; we judge them not by the moment-by-moment experience of pain, but by a comparison of the worst pain with the end-point. If we experience severe pain followed by discomfort - as in an attack of gout - our memory of the episode is not as unpleasant as it would be if we experienced ever-increasing levels of pain and then a sudden stop.

This pattern fits in with George Osborne's rising approval ratings. Living standards are still squeezed, but less so than a few months ago. Pain has thus given way to discomfort, which means the peak-end rule makes austerity feel good.

Although this rule describes our retrospective assessment of pain, it is irrational in two ways.

First, one corollary of the rule is duration neglect; our memories of painful episodes aren't well correlated with the length of such episodes.

Secondly, the rule implies that adding discomfort to the end of a period of pain can actually improve our memory of that period - even though the discomfort is unnecessary. As Kahneman wrote: "adding a period of diminishing discomfort to an aversive episode makes it globally less aversive." This means that, in retrospect, we look favourably upon gratuitous discomfort.

Public approval of Osborne isn't based merely upon bad economics, therefore. It's founded in psychological mechanisms which distort judgments. "Bourgeois" social science corroborates the Marxian claim that political beliefs can be subject to false consciousness.

One other thing. Kahneman's theory is based upon a study (pdf) of colonoscopy patients. In this sense, George Osborne is very much like a pain in the arse.

May 6, 2014

When labour isn't fungible

Tim Worstall gives us a nice example of the classical liberal mindset. Objecting to Owen's talk of the "trauma" of deindustrialization, he writes:

People have moved away from an activity that no longer adds value to other occupations that do add value. And so does the human species become ever richer, as we move capital and labour from low...activities to higher value adding ones.

The same is true of the manufacturing in the North that people so decry the disappearance of. The game is all about adding value and if it turns out that staffing an old folks home adds more that humans value than does making thing to drop on your foot then we're richer for the change in what people do.

In saying this, Tim is committing the error I've accused some classical liberals of making; he's mistaking the map for the terrain. He gives a good account of how a well-working labour market should work. But he fails to ask: is this how the market works in reality? And the answer is: maybe not. The fact unemployment rates are high in many areas that experienced a lot of deindustrialization alerts us to the possibility that labour isn't completely fungible; workers made redundant in heavy industry don't swiftly become care home workers. One study of the effect of pit closures in the 1980s found (pdf):

Between 1981 and 2004, 222,000 male jobs were lost from the coal industry in [mining] areas; this was offset by an increase of 132,400 in male jobs in other industries and services in the same areas.

You might object that 132,400 out of 222,000 means Tim is more than half-right. But this omits the fact that unemployment is a massive source of misery. Even if the transition from miner to care home worker does eventually occur, the temporary joblessness during the shift isn't just a waste of resources, but a big loss of happiness.

In this context, Tim is too sanguine about relative decline. He says: "going from being a comparatively rich part of the country to being a comparatively poor one is not the same as becoming poorer or impoverished." This overlooks the fact that relative poverty matters. As Adam Smith - who gave his name if not much else to the Adam Smith Institute - wrote:

By necessaries I understand not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life, but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without. A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt, the want of which would be supposed to denote that disgraceful degree of poverty which, it is presumed, nobody can well fall into without extreme bad conduct.

In saying all this, I don't mean that Tim is entirely wrong. He's right that, over time, labour must shift; we need care workers more than a stovepipe hat factory. Tim's error, instead, is to understate the pain - and time - involved in this shift.

In doing this, and in writing of the human species becoming richer, Tim is coming close to the view that the happiness of some individuals must be sacrified for the welfare of the collective. Which seems to me to be nearer to Stalinism than to classical liberalism.

May 5, 2014

Keeping the rich rich

Andrew Lilico says:

I would prefer a system in which the wealthy were allowed to lose their money if their investments go bad, in which the state does not intervene in the economy to keep the rich rich. I grant that we do not have such a political system now – the bank bailouts of 2008 and since have made that clear to everyone.

The bailouts, though, are only a small part of the story here. There are countless other ways in which the state helps keep the rich rich, for example:

- The state enforces property relations, including intellectual property rights. "Private property cannot survive without the guarantee of government" says Ferdinand Mount, who's hardly a rabid leftie. This guarantee, though, is asymmetric; if you have a troublesome tenant, the police might turn up mob-handed. But if you have trouble with your phoneline, they are unlikely to raid BT's offices.

- Planning restrictions help to keep house prices high, to be the benefit of landlords, and help to maintain local near-monopolies for example by restricting the number of retailers in an area.

- The state played a key role in the process of primitive accumulation - imperialism and slavery - which provided a basis for capitalist wealth today. It wasn't Marx who wrote "All rights derive from violence, all ownership from appropriation or robbery", but von Mises.

- Government spending is a form of corporate welfare. At its best, it helps sustain demand for capitalist products. And at its worst - for example in overpaying for military equipment, paying for welfare-to-work programmes that don't work or just outright fraud - it gives capitalists something for nothing.

- The ordinary welfare state helps the rich too. Most obviously, housing benefit subsidizes landlords. But it's also the case that welfare benefits help underpin and stabilize aggregrate demand, and help to maintain a supply of labour, all of which benefits capitalists.

In saying all this I'm not denying that inequality wouldn't arise in a freed market. My point is just that such inequalities - the Robinson Crusoe example Andrew gives - would be very different from the inequalities that actually exist now.

Nor am I denying that there might be a case for such massive state intervention. When investment is in private hands, it will only occur if those hands can be reasonably certain of a return. In this sense, economic growth - at least within a capitalist economy - requires the state to guarantee capitalists' wealth.

Instead, my point is simple. If Andrew is serious about wanting the state not to intervene in the economy to keep the rich rich, he must adopt a very radical position indeed. I warmly welcome him into the left-libertarian fold.

May 2, 2014

Citizens vs economists

Ha-Joon Chang says:

Economics is not a science...Very often, the judgments by ordinary citizens may be better than those by professional economists.

He doesn't provide any empiricial evidence for this - that would be too scientific. But I suspect it is true in one sense, and false in others.

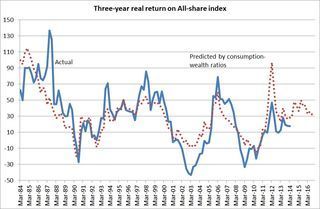

It's true in that citizens' - or at least consumers - judgements can do a better job of economic forecasting than the experts. My chart shows how the ratios of consumer spending to house and share prices have done a decent job of forecasting stock market returns over the last 30 years*; this is a simplified version of the famous Lettau-Ludvigson result (pdf), as corroborated by some Bank research.

The idea behind this is a wisdom of crowds one. If individuals anticipate better times, they are likely to spend more and so consumer spending will be high relative to wealth. If they anticipate bad times, spending will be low. Whilst any individual might be mistaken, their errors cancel out, with the result that aggregate spending forecasts share prices and economic growth. This is a Hayekian finding: there's wisdom in the dispersed, fragmentary knowledge of millions of people.

1-0 to Chang.

But in other respects, he's wrong. Brad Barber and Terrance Odean have shown that, around the world, most individual equity investors under-perform the market.This tells us that ordinary citizens know less than the experts - because expert advice is to invest in trackers. The efficient market hypothesis of economists might not be perfect, but most individuals would do better if they heeded it.

This poses the question. If ordinary people do worse than experts when they are investing their own hard cash, won't they be even stupider when they don't have skin in the game. Three facts make me think so:

- George Osborne has a high approval rating, even though orthodox economics, as Simon is sick of telling us, tells us that his actions delayed the recovery**.

- Many people want benefit cuts, in ignorance of how mean they really are.

- Most people think immigration has been bad for the economy - in contradiction of most of the scientific evidence.

In these respects, I prefer professional economists' judgments to those of citizens. And I suspect Mr Chang and his readers would too.

This is not (just) a conservative, orthodox opinion. One famous heterodox economist cautioned against relying upon people's opinions of appearances and demanded a scientific approach which looked behind them. "All science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided" he said.

In truth, I'm not sure Mr Chang believes what he's saying. When Cambridge's economics exams are marked, I suspect it will be by professional expert economists and not by ordinary citizens. But then, radicalism usually stops when it challenges one's own ego and power.

* The equation here is: 2.12 x consumption/All-share index ratio) + (3.07 x consumption/house price ratio) - 212. House prices are from the Nationwide, consumption from the ONS.

**There's always a danger of falling into "no true Scotsman"-type thinking in defining orthodox economics, but I reckon that if something's taught to first-year Oxford students, then it's orthodox.

May 1, 2014

Egalitarianism in the lab

Which sort of inequalities should we tolerate and which should we remedy?

One respectable philosophical position here is that of luck egalitarianism. This distinguishes between brute luck and option luck: option luck describes the outcome of gambles we have chosen, whereas brute luck describes luck beyond our control. The luck egalitarian would equalize the outcome of brute luck, but not that of option luck. He would compensate someone who loses their job in a recession, say, but not someone who loses their money in a casino.

You might not agree with this view, but it's surely tenable.

Here, then, is a surprise. In a laboratory experiment, almost nobody is a luck egalitarian.

Johanna Mollerstrom, Bjorn-Atle Reme and Erik Sorenson gave people $24 and told them they faced three equiprobable scenarios. In A, they would keep the money. In B and C, they would lose it. However, they were given the choice to buy insurance against scenario B, but not C. Scenario B is therefore a case of bad option luck, whereas scenario C is bad brute luck.

152 subjects at Harvard Business School were then faced with pairs of subjects who had experienced these scenarios and given the choice to equalize incomes within the pair. And here's the strange thing. Whilst there was a decent minority of strict egalitarians, who equalized in all scenarios, and of "libertarians" who never equalized, only one of the 152 subjects was a consistent luck egalitarian.

Instead, many subjects were what they call choice compensators. They were more likely to compensate people who suffered scenario C if they had bought insurance against scenario B than if they hadn't - even though that choice made no difference to their loss.

There might be a justification for this. Buying insurance signals that you are risk-averse, so losses hurt more - and subjects are keener to compensate people for if they face a painful loss.

However, something nastier might be going on. Maybe subjects want to reward "good" behaviour - buying insurance - even if that behaviour is irrelevant for the outcome in question. Worse still, some might be looking to blame the victim, and see not buying insurance as a sign of recklessness.

It's in this context that a lot of political rhetoric makes sense. If you think the poor are "hard-working families", you'll be think they made the right choices and so deserve redistribution. If instead you think they are lazy scroungers, you won't. Those of us who point out that laziness and scrounging might be irrelevant for actual outcomes are missing the point; people are looking for a moral basis for redistribution, not for a causal link between behaviour and outcomes.

Now, in these lab experiments, subjects didn't have to use their own money to equalize. In the real world, where there's a self-serving bias, people will be even keener to find reasons not to redistribute.

We should, however, remember that there is a difference between what's right and what's popular. The fact that almost nobody is a luck egalitarian is not sufficient to show that luck egalitarianism is wrong.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers