Chris Dillow's Blog, page 128

March 21, 2014

Fairness and the majority

Richard Murphy touches on an issue which, though neglected, divides political activists from many observers, and social democrats from Marxists. He says: "[when] it comes to fairness majority opinions matter."

Now, this is true in the sense that a society whose policies and institutions violate the majority's perceptions of fairness will be an unstable one - as nation-builders often discover.

Where it is doubtful, though, is whether majority opinion decides what's fair.

There's a long tradition in ethical thinking, from the book of Exodus - "Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil" - to Amartya Sen (pdf) and some interpretations of intersectionality which doubts the ability of the majority to decide what's fair.

Most of us would accept these doubts in the context of other societies. We don't think the repression of women and gays is fair in Saudi Arabia, nor that it was fair in the past, merely because most people in Saudi Arabia or in early 20th century England thought them so. The statement: "slavery was fair once" would strike most of us as absurd, or at least as requiring a lot of justifying.

But why should we suspend such doubts in today's Britain? Most people - to take one example - agree with the statement: "it is fair that foreigners should be excluded from much of the UK labour market." But a few decades ago, most would have agreed with the statement: "it is fair that women should be excluded from much of the labour market." What, morally speaking, is the difference? Could it be that we see one merely because Peter Singer's "expanding circle" of concern has expanded to include women but hasn't yet expanded to include foreigners?

Let's face it, the standard of public "debate" about moral questions is not high; most claims about morality are mere emotivist spasms or expressions of narcissistic self-righteousness.

I suspect - though this might be the confirmation bias! - that recent thinking has deepened scepticism about the ability of the majority to perceive what's fair. Cognitive biases such as the just world fallacy, stereotype threat, adaptive preferences and anchoring effect help to provide popular support for inequality; John Jost calls this system justification (pdf).

It's in this context that there's a difference between Richard and me. He says:

On the welfare cap I have no doubt the majority will consider what is being proposed to be profoundly unfair if they realise just who is affected.

But I don't much care what the majority thinks; the cap is either fair or not, regardless of what the majority think.

This difference reflects two differences between us. One is that Richard's a social democrat and I'm a Marxist. Whereas social democrats try to work within the confines of what the public considers "fair", and try to tweak those perceptions, we Marxists fear that this is a forlorn task because the power of ideology warps those perceptions.

The other is that Richard is an activist and I'm an observer. And in a democracy, success as an activist is determined by what the majority think - by whether you win elections; how often do we see politicians cite opinion polls as if they decided matters?

And this is what bothers me. Public opinion might decide what is a successful political strategy, but it is more questionable whether it should decide what is a morally right one. One of my fears about Labour politics is that this distinction is often ignored.

March 20, 2014

Ex-growth

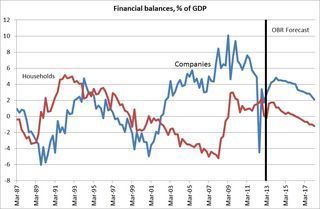

Once upon a time, we used to think that the function of the financial system was to channel savings from households - who were savings or for a rainy day - towards companies who could invest them productively*. That world has gone, and it won't return for some time if you believe the OBR's forecasts.

These show that whereas companies are expected to run a financial surplus throughout the next five years - albeit at a declining rate - households are expected to start to run a deficit.

If the OBR is right, this means that, by the end of this decade, we'll have seen 18 years in which (except for one quarter) companies have run a higher financial balance than households.

This stands on its head the old-fashioned image of financial intermediation. This now consists of transferring corporate savings to households, to spend on housing.

Now, of course the OBR's forecasts might well be wrong; forecasts are. But they seem plausible. If we see a normal upturn the share of profits in GDP will rise, as mass unemployment continues to hold wages down. Allied to a continued (if slightly lesser) dearth of investment opportunities, this will keep retained profits higher than capital spending. Meanwhile, households could respond to that squeeze on wages by saving less.

This picture is consistent with the corporate sector having gone ex-growth. It's common for large mature companies such as Next to generate more cash than they can usefully invest. "UK plc" generally has been in this position for several years, and the OBR expects it to remain so.

Curiously - as with the productivity collapse - George Osborne failed to mention this in his speech yesterday.

But it surely is of immense significance; can an economy really prosper for long merely by building and selling houses? There are two big questions here: is there anything that could usefully be done to expand investment opportunities, or to get firms to better use the few that do exist? And/or: should we think more about the policies we need in an economy that's gone ex-growth?

I'm not sure of the answers here. But as I've said before, I wouldn't mind if our political class at least bothered to ask them.

* Yes, I know banks create money. I'm talking here about shifts of real resources.

March 18, 2014

"Subsidizing" childcare

It's fitting that Nick Clegg should have announced an increase in the state subsidy for childcare, because the policy is a sanctimonious front for something that is inegalitarian and economically illiterate.

Let's start from the fact that this subsidy must be paid for by other tax-payers. It's therefore not just a subsidy to parents, but a tax on singletons.

This is inegalitarian not just because it means that a single person on the minimum wage is subsidizing the lifestyle choice of couples on six-figure incomes. It's inegalitarian in two other ways.

First, the costs of a family don't rise proportionately with household numbers. The cliche "two can live as cheaply as one" isn't literally true, but it is partly so. This is captured by the notion of equivalence scales, which adjust household incomes for family size. Such scales tell us that a household with two adults and a young child needs an income of 1.8 times that of a singleton. But this in turn means that if two people in a couple have similar incomes - and given assortative mating many do - then the couple is better off than the singleton. Subsidizing childcare is thus regressive in many cases.

Secondly, there's reasonable evidence that marriage improves people's mental and physical well-being. This means a tax on singletons to help couples is welfare-regressive; it gives to those who have.

Why, then, do it? Simple. Couples with children have political power; politicians defer to Mumsnet, and yet many people sneer at "spinsters with cats". All we're seeing here is another example of politicians trying to give money to the powerful. Clegg's claim that this is about a "fairer society" is mere blather.

The policy is also economically illterate because it ignores two important economic ideas: fungibility and incidence.

A childcare subsidy is fungible; if parents are spending less on childcare, they've more money for something else. A lot of child benefit is spent on alcohol. The same might well be true of the childcare subsidy.

There's one sense, though, in which this isn't entirely true. Not all of the subsidy will benefit parents. This is where the concept of incidence comes in. Let's say the policy works as some hope it will, and encourages mothers (or dads) to look for work. Two things will then happen: the extra labour supply will bid down wages; and insofar as parents find work there'll be extra demand for childcare, which will tend to bid up prices of it.

Insofar as this is the case, the childcare subsidy doesn't just benefit parents, but employers and nurseries.

There is, though, another sense in which the policy is economically illiterate. The opportunity cost of subsidizing childcare is that money could be spent on genuinely giving children the best possible start in life, by more investment in early years education, especially for kids from poor homes. Clegg has foregone this opportunity, and would rather give yummy mummies another bottle of Chardonnay.

March 17, 2014

Memories, & mechanisms

In the LRB, James Meek suggests that support for pan-Russianism is helped by generational change:

Many of the most articulate and thoughtful Russians and Ukrainians, those of middle age who knew the realities of Soviet life and later prospered in the post-Soviet world, have moved abroad, gone into a small business or been intimidated: in any case they have been taken out of the political arena.

In Russia and Russophone Ukraine the stage is left to neo-Soviet populists who propagate the false notion of the USSR as a paradisiac Russian-speaking commonwealth, benignly ruled from Moscow...If you were born after 1985 you have no remembered reality to measure against this false vision.

This hints at an interesting mechanism in the social sciences - that change can happen simply as one generation forgets what an earlier one knew. As George Santayana said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

My favourite example of this is Andrew Newell's explanation of why the inflation/unemployment trade-off worsened in the late 60s. It was, he says, because a generation of workers who remembered the depression of the 1930s retired and were replaced by a generation that had known nothing but security and full employment and so were more emboldened to push for higher wages.

The same could be true in financial markets. It's sometimes said - in a variation on Minsky's financial instability hypothesis - that stock market bubbles occur after a generation that remembered previous crashes has retired; given short careers in the City, this happens quite often.

It's possible that a similar thing happens in attitudes to wars. It might be that the US and UK became keener on overseas adventures as memories of Vietnam and Suez faded.

The psychology behind this is Humean. Our actual lived experience gives us impressions which enter our mind with "force and violence." But the experiences of our parents and grandparents which we only hear or read about are mere ideas, which are only faint images of impressions.

So far, so good. But this is only half the story. It is also possible for the experiences even of distant generations to affect our behaviour now. For example, Germany's experience of hyper-inflation in the 1920s makes them inflation nutters today; Greeks' experience of Ottoman rule has made them disinclined to pay tax; and slavery has had a long-lasting economic and perhaps psychological impact.

Sometimes, then, historical memories fade and sometimes they linger - in both cases with material consequences.

This is not a contradiction. What we have here are two separate mechanisms through which history can cause social change - in one case because it's forgotten, in another because it's remembered if only viscerally. All of which vindicates Jon Elster:

It is sometimes said that the opposite of a profound truth is another profound truth. The social sciences offer a number of illustrations of this profound truth. They can isolate tendencies, propensities and mechanisms and show that they have implications for behaviour that are often surprising and counter-intuitive. What they are are more rarely able to do is to state necessary and sufficient conditions under which the various mechanisms are switched on. (Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, p9)

March 14, 2014

Credit controls & the crisis

Richard Murphy says that the Bank of England's statement (pdf) that banks create money by lending means there is a case for credit controls. I fear he's being a little hasty.

It is of course true that banks create money by lending; I'm surprised that anyone should be surprised by the Bank's statement of the obvious*. But that is not the only way in which banks affect the money stock. They also do so by issuing shares or bonds. If they issue shares, the money stock falls and if they buy shares it rises; this process is measured by net non-deposit liabilities in table A3.2 here.

And here's the thing. The problem we had in the run-up to the crisis was not simply that banks were creating loans and therefore money. It's that this money creation was not matched by issues of capital. The ratio of banks' total assets (mostly loans) to their equity rose. This suited bankers because the higher the ratio of assets to equity, the higher is return on equity in good times and so bank bosses can claim higher salaries; Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig are good on this.

It was this high asset-to-equity ratio that got banks into trouble. RBS and Northern Rock didn't fail because lots of their loans turned bad. RBS failed because it didn't have a sufficient equity cushion to absorb losses at ABN Amro. And Northern Rock failed because it had funded loans by borrowing in wholesale markets, and those markets seized up in 2007.

Quantitative credit controls wouldn't have prevented all this. At a time when banks wanted to leverage up, such controls might instead have caused them to buy back equity. This would have left them vulnerable to losses on bad takeovers or to a loss of interbank liquidity.

Instead, what we needed was better prudential regulation (or public ownership!) to ensure banks had an adequate equity base; quantitative credit limits, in themselves, do not achieve this.

I stress this point for a reason. I fear that we're in danger of misdescribing the financial crisis. It was not so much a macroeconomic failure, caused by high debt, as an organizational failure; bad management led to over-extended balance sheets, and shareholders failed to stop this. In this sense, the crisis was a failure of hierarchical capitalism and not something that could have been prevented through better macroeconomic management.

In saying I don't mean to deny that there might be a case for quantitative credit controls. If there is such a case, it lies in stories of adverse selection and asymmetric information; high interest rates mean that only reckless or confident borrowers apply for loans. In such a world, quantitative limits might be superior to interest rates.

However, such limits don't follow automatically from the Bank's description of the money creation process, and they aren't sufficient in themselves to prevent banking crises.

* Maybe because I've tended to regard textbooks as a help in passing economics exams rather than as a means of understanding the economy.

March 13, 2014

Openness in policy-making

On Twitter, Ben Chu has asked for a counter-argument to Chris Giles' call for the Bank of England to follow the Fed in publishing full transcripts of MPC meetings. I think such an argument exists, but that it draws attention to a general failure of public debate.

The argument - as Chris acknowledges - is that it might stifle debate. I find this plausible. The economy is a complex, emergent process which is inherently unpredictable. What's more, the economy isn't merely risky, but uncertain. We don't know where the big dangers will come from; for example in the mid-00s everyone told us that current account imbalances and hedge funds were a threat to financial stability, but few told us that banks were.

This means that, after the passage of time, many contemporaneous statements about the economy will look wrong. Not only will forecasts be wrong, but we'll be worrying about risks that don't materialize and not worrying about ones that do.

With hindsight, everyone looks daft. The claim that publishing transcripts will make some MPC members reluctant to speak, for fear of looking silly in a few years' time, is therefore one I find plausible.

But its strength rests upon two aspects of our culture which are questionable.

The first is an excessive faith in experts. If you believe the economy is predictable and controllable by men of good judgment, then errors are something to be excoriated. Such a view will stifle debate.

But this is the wrong frame. Errors are inevitable. We should therefore judge people not by whether they happen to be right, but rather by whether their beliefs were rational - that is, proportioned to the evidence as it existed at the time. From this perspective, it would be wrong - and possibly irrational - to decry people for being wrong. If this were so, MPC members would feel less constrained by the threat of future publicity.

The second problematic aspect is the presumption that the role of experts is to express their personal opinion.

But it needn't be so. An expert isn't merely some guy with an opinion. It is someone who is capable of giving the strongest possible argument and counter-argument for a case - who knows all the perspectives on an issue and the evidence and counter-evidence. (This is what I was trying to do in yesterday's post).

This points us to another way of organizing MPC meetings. Someone could be designated an "inflation nutter" and tasked with providing the best argument for raising rates; someone else could be the "dove"; someone else the worryguts about financial risk, and so on. (I'm thinking here of a variant of De Bono's six hats). If any MPC member can't fill such roles, he's probably not qualified to be on the committee.

Such a structure would create rigorous constructive debate whilst avoiding the twin evils of groupthink or a conflict of egos. It would also free MPC members from the fear of future criticism for being wrong, because the views they expressed would be those of their roles not their selves.

Of course, members would have to step out of their roles to vote on policy. But this doesn't bear upon the issue of publishing transcripts, simply because members' votes are recorded in the minutes of meetings.

I say all this not to say that Chris is right or wrong to call for publication of transcripts. Rather, it's to suggest that, if he is wrong, the problem lies not so much with his argument as in the defective nature of the way policy is organized and debated.

March 12, 2014

Arguing against immigration

James Brokenshire's recent speech on immigration has been widely decried as one of the worst ever. This poses a question: is it possible to make an intelligent case against immigration? Here's how I would try.

The economic evidence tells us that immigration is good for the economy. But economics also tells us something else - that this doesn't much matter. As Andrew Clark says, "the rising trend in GDP per capita is certainly not matched by an analogous movement in average happiness". Whether the Easterlin paradox is really true or only roughly so needn't detain us. What matters is that the welfare gain from economic growth is small.

What does affect well-being, though, is friendship (pdf). Happiness research tells us that this is great for well-being. However, for whatever reason, inter-ethnic friendships are rare, both in the UK and US. I suspect a similar thing is true for nationality; how many of you count Romanians or Bulgarians as friends? This suggests that mass migration might increase social isolation - which matters more for well-being than money.

This point widens. There's some evidence that, at least in unequal (pdf) nations and poor (pdf) communities, immigration can reduce social capital. As Ben says, there might be a link between immigration and the UK's increasingly atomized society.

You might reply that the solution to this is for immigration to occur against a background of greater equality. If more of us were comfortable, there'd be less suspicion of immigrants.

But immigration might, ultimately, erode demand for redistributive policies. One reason for this is that the act of migrating is an individualistic one, and parents might transmit such an individualistic mindset to their children, which would create a culture hostile to collectivism and redistribution. Is it really just a coincidence that the one developed nation founded upon immigration just happens to be the one that historically has lacked a major socialist party or tradition?

Another reason is more unpleasant. It's that ethnic diversity reduces demand for egalitarian policies; people are happier to fund welfare states if the money is helping their "own kind." "Racial cleavages seem to serve as a barrier to redistribution throughout the world" concludes one study (pdf).

All this shouldn't merely worry lefties. It's quite plausible that decent welfare states are good for the wider economy, because they help smooth out macroeconomic fluctuations and so reduce business uncertainty. This could - in the long-run - mitigate the economic benefits of migration.

Now, I'm not sure I subscribe to the above. I've raised issues about the relevance of happiness research; the trade-off between liberty and social capital; the distinction between changes and steady states; and the role (if any) that dirty preferences should play in politics.

But my opinion doesn't matter. My point is that it is possible to make a reasonable argument against immigration which doesn't degenerate into economic illiteracy, racism or sneers at "metropolitan elites." Which kind of makes me wonder why it's so rarely heard.

March 11, 2014

On compensating advantages

Milena Kremakova asks:

Why is it that in our society, there seems a general rule that, the more obviously one’s work benefits other people, the less one is likely to be paid?

There's a perspective here that I feel is under-rated, and it's one that's consistent with both friendly (pdf) and unfriendly explanations of the rising incomes of the rich. I'm thinking of Adam Smith's idea of compensating advantages.

This says that differences in pecuniary rewards are offset by non-pecuniary advantages. Smith gave the example of miners who were well-paid relative to other labourers, as compensation for having to work in dark and dangerous conditions.

I've long had sympathy for this view; I earn much less now than I did when I worked in the City, but this is offset by having more interesting and enjoyable work and nicer surroundings.

This helps answer Milena's question. If your work helps others, you can take satsifaction and self-respect from this. To offset this pleasure and pride, money wages are low. By contrast, if you're a boss, you might feel a sense of persecution or disrespect from some people you'd rather impress: in the words of the great Natalia Boa Vista, "executives are right down there with paedophiles." For this reason, you'll be well-paid for the same reason Smith thought actors and opera-dancers were well-paid - to compensate for the discredit of being in such professions.

You might reply here that the egomania of those in top jobs insulate them from feelings of shame - as we've seen recently with Bernard Hogan-Howe's claim that he's the best man to lead the Met and Danny Cohen's belief that he's underpaid.

Such narcissism, however, has a drawback. It means one is never happy with what one has got; you feel that you deserve more money and acclaim: as the song goes, it's so hard to find one rich man in ten with a satisfied mind.

We have two pieces of empirical evidence here.

One comes from Andrew Clark. It's that although income inequality (defined by the share of the 1%) has risen in recent years, happiness inequality has declined. The other is that the correlation between individuals' incomes and well-being, though positive, is low. For example, Nattavudh Powdthavee's work (pdf) suggests that raising one's salary from £100,000 to £200,000 increases well-being by only around 0.14 points on a 1-7 scale.

These findings don't support the idea that differences in income are wholly offset by non-pecuniary rewards. But they do suggest that there's perhaps a hefty mitigation.

My point here is not that we should pity the rich. Instead, it's to challenge social democrats' opinion about why inequality matters. The problem is not so much that some people are living very well at the expense of others; a focus on incomes exaggerates the extent to which this is the case. Instead, it matters to the extent that inequality (or the forces that cause inequality) has adverse social and economic effects.

March 10, 2014

The power of the 1%

Simon asks why there's so little outrage about the high incomes of the top 1%. Let me deepen this question.

I suspect that one reason is that people don't see top incomes as affecting them; they don't look at Euan Sutherland's pay and think "that's coming out of my pocket".

But this lack of reaction is contestable. It's quite possible that we would be better off if the top 1% were less well-paid.

Simple maths tells us that if the income share of the top 1% could be reduced from its current 12.9% to 9.9 per cent - its level in 1992 - then the incomes of the 99% would rise 3.4%, equivalent to a gain of £72 per month for someone on £25,000 a year.

Of course, this calculation only makes sense if we assume such redistribution could occur without reducing aggregate incomes. But such an assumption is at least plausible. The idea that massive pay for the 1% has improved economic performance is - to say the least - dubious. For example, in the last 20 years - a time of a rising share for the top 1% - real GDP growth has averaged 2.3% a year. That's indistinguishable from the 2.2% seen in the previous 20 years - a period which encompassed two oil shocks, three recessions, poisonous industrial relations, high inflation and macroeconomic mismanagement - and less than we had in the more egalitarian 50s and 60s.

What's more, there are reasons to suppose that the disease of which high top pay is a symptom - the managerialist ideology which empowers CEOs to enrich themselves - is bad for the economy:

- It encourages short-termism, as managers try to deliver financial results to justify their high pay at the expense of long-term investment and research.

- CEOs who think of themselves as heroic leaders can become emboldened to take reckless decisions, especially if they refuse to countenance criticism and so, in Ken Boulding's phrase (pdf), end up "operating in purely imaginary worlds.“ Fred Goodwin's disastrous takeover of ABN Amro wasn't an idiosyncratic failure, but rather the result of the cult of narcissistic bosses.

- Leader-dominated organizations can demotivate junior staff who look to the top for guidance rather than solve problems themselves. This problem can be exacerbated because staff in top-down organizations are often insufficiently well supervised and thus prone to skiving and thieving. There's reasonable evidence that organizations which empower workers (pdf) are more productive than those that don't.

It's a reasonable hypothesis, then, that the power of the 1% is bad for the economy.

However, in popular discourse, this hypothesis is not so much explictly rejected as not even considered, whereas the idea that immigration is bad for the economy is widely accepted even though it's wrong.

What can explain this? Simon blames the media. But I'm not sure this is the whole story.

For one thing, there has been cross-party support for the 1%. New Labour rarely saw a boss it didn't cringe towards, and social democrats main gripe with power has long tended to be not that it is too concentrated but that it just happens to be in the wrong hands. And for another, we shouldn't write off false consciousness: cognitive biases can indeed help to sustain inequality.

Whatever the cause, the fact is that the lack of outrage about CEO rip-offs is itself evidence of the great power they have - the power to keep some debates off the agenda. As Steven Lukes wrote:

Is it not the supreme and most insidious use of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural and unchangeable? (Power: A Radical View, p28)

March 7, 2014

Ukip's strange "libertarianism"

Ukip councillor Donna Edmunds has said that shop-owners should be free to refuse to serve women or gays: "I'm a libertarian so I don't think the state should have a role in who business owners serve."

As an expression of ultra-libertarianism this might just about be defensible in itself. But it runs into a problem. If you think people should be free to choose whom they sell to, shouldn't they also be free to choose to sell their labour to whichever willing buyer wants it?

But Ukip wants to deny them this right. It wants tough immigration controls. Not only are these curbs on the rights of sellers, but they also infringe the rights of business owners which Ms Edmunds is so keen to assert: if businesses should be free to refuse to serve gays, shouldn't they also be free to hire whomever they want? We have a very selective form of libertarianism here.

In itself, of course, this is no biggie. Most of us believe that some liberties should be restricted. But it's difficult to see the grounds for selection in Ms Edmunds' case. It's hard to believe they are consequentialist ones. We know that immigration has economic benefits, so you have to impute large cultural costs to it to want it restricted. This is a tenable position in itself - albeit not one I share. But there are surely also cultural costs in permitting business owners to refuse to serve gays; doing so fosters a homophobic atmosphere. It's hard to see a reason for liberty in the one case but not the other.

It would be easy to dismiss Ms Edmunds as the kind of fruitloop we could find in all parties.

But there's something else. Nigel Farage has defended the right of a "comedian" to tell racist "jokes." Again, in itself such a view is tenable. But again, we run into the problem: why be so libertarian in defending racists and so anti-libertarian about immigration?

What we're seeing in both cases is what I've called asymmetric libertarianism. It's libertarianism for bigots but not for foreigners. There's a word for this. It begins with R.

On this, I'm with Peter Risdon: fuck Ukip.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers