Chris Dillow's Blog, page 132

January 30, 2014

Tax rises vs immigration caps

The 50p tax rate is probably getting more attention than such a minor measure deserves. But there's a point here that's been missed - that there's a parallel between higher taxes on the rich and immigration controls. Both policies, their critics allege, have similar effects: they reduce the supply of skilled workers and entrepreneurs.

Which poses the question: how can one support an immigration cap but oppose higher taxes on the rich, as many Tories do?

The question's acute because a tax rise has a marginal effect on labour supply - and might even have a positive one if income effects outweigh substitution effects - but immigration controls have a direct effect. A 50p tax might at the margin stop some people coming to the UK to start businesses.But immigration controls certainly do.

There's one answer to this puzzle that's obvious gibberish - that the case against higher taxes is a matter not just of economics but of freedom. However, stopping a man hiring whom he wants is probably as much a restriction of his freedom than taxing him more. And stopping someone working here is surely a greater restraint than higher taxes.

Instead, I suppose the argument is that exceptions to the immigration cap can be made for entrepreneurs and skilled staff. This is the Simon Cowell theory of the state - the idea that governments can act as talent-spotters.

This theory runs into problems.

First, it doesn't work now; there's agreement that current immigration controls are so tight as to deprive businesses of some key workers.

Secondly, a cap on poor and unskilled migrants would deprive us of high-quality talent simply because many of these - and their children - go on to become skilled workers and successful entrepreneurs. In the better parts of Leicester you can't throw a brick without hitting a rich man who arrived in England in just the clothes he was stood in. And if we'd excluded poor migrants in the past, we'd have not have had entrepreneurs such as Lew Grade, Isaac Wolfson or Charles Forte,not to mention more Indians than you can shake a stick at, and we'd not have household name firms such as Tesco and Marks & Spencer.

Let's, though, ignore these objections and assume - contrary to everything Hayek thought - that the state does have the knowledge to act like Simon Cowell. This only poses the question: if government is smart enough to spot talented migrants, isn't it also smart enough to do other things Conservatives oppose, such as intervene in or even control large parts of industry?

My point here is simple. It's quite coherent (though perhaps wrong) to support both tax rises and immigration controls - say because you doubt that tax rises have adverse effects or because you think that social cohesion trumps economic efficiency. And it's entirely consistent (though perhaps wrong) to oppose both, as proper libertarians do. What I have a problem with are those Tories who oppose tax rises whilst supporting immigration caps. Doing this requires some considerable mental gymnastics.

January 29, 2014

Deficit fetishism

There's a lot of public finance fetishism around, for example:

- Ed Balls promises to balance the government's current budget by 2020, without conditioning this on the state of the economy.

- People are questioning whether the taxpayer will ever recoup the money invested in RBS - ignoring the fact that if RBS hadn't been bailed out we might have had an even worse financial crisis which would have left us all poorer.

- The debate about the 50p tax rate has been mostly about whether it would raise revenue or not, when what really matters is its impact (or not) upon GDP.

- Owen Jones says a living wage would "save billions spent on social security", without noting that this is a bug, not a feature; it means a living wage, in itself, would be a fiscal contraction.

Underpinning these cases is the fallacy of petitio principii, or begging the question. Something is assumed which must in fact be proved - that the public finances matter. Given that the people lending to the government are happy to do so at nugatory interest rates, this is a big assumption. It also assumes that Keynes' words - "Look after the unemployment, and the Budget will look after itself" - are no longer relevant, without any proof that this is so.

You might reply that there is proof. The OBR estimates that there's a cyclically-adjusted (or "structural") deficit of 4.4% of GDP - which implies there'd be a deficit even if we did look after unemployment.

I'm not so sure. Estimates of the cyclically-adjusted deficit are massively uncertain, in part because they depend upon the mumbo-jumbo idea of the output gap. The best way of telling whether we have a structural budget deficit is to get the economy back to an acceptable level of activity, and then see what the deficit is. Let's look after today's problem today - of six million unemployed - and tomorrow's problems (if they exist) tomorrow.

But let's say we get to a reasonable level of activity, and there's still a deficit. What then?

By accounting identity, this can only mean that the private and/or overseas sectors are running surpluses - saving more than they are investing. Such surpluses are potentially demand-deflationary, in which case a fiscal tightening would add to upward pressures on unemployment.

What's more, if the private and overseas sectors are net savers, they are likely to be big demanders of safe assets - in which case demand for gilts might keep their yields relatively low. And if real yields are below trend growth, then a deficit is sustainable. (And if this isn't the case because

trend growth is low, then we have a bigger problem than the public finances.)

Now, I'll concede - unlike many MMT-ers - that it is theoretically possible that the deficit might matter: maybe investors would take fright at it and dump gilts and Bank of England buying of gilts might not solve this problem in a non-inflationary way. But this is a long story which needs to be

demonstrated. It is not good enough to merely assume this is a genuine threat and to assume the public finances matter - and even less good to jeopardize jobs on the basis of that assumption.

Instead, I fear that the importance given to the public finances in the public's mind rests upon some simple errors, such as silly talk about the "nation's credit card" and the daft idea that the public's finances are the nation's finances.

It might be good politics to pander to such irrationality, as Ed and Owen seem to be doing. But let's remember that good politics and good economics only rarely overlap.

January 28, 2014

Adnan Januzaj, & counter-signalling

It's not been often recently that Man Utd players have invited comparisons with some of the greatest geniuses of the last hundred years, but Adnan Januzaj has achieved this feat. Reading about his hapless date at Nando's reminded me of Richard Feynman and Hank Williams.

What I mean is that all three give us examples of counter-signalling, or showing off by not showing off.

Plain signalling is very common. People go to university to try to signal to prospective employers that they are smarter than they really are, and they engage in expensive (pdf) conspicuous consumption to signal that they are richer than they really are.

Mr Januzaj, however, has done the opposite.In taking Ms McKenzie on a needlessly cheap date, he was counter-signalling - giving the impression that he was poorer than he really was.

This is where a parallel with Professor Feynman enters. When he was at Caltech, he used a topless bar as his office. This too was a counter-signal. He was signaling that he wasn't a pompous poker-up-the-arse academic, but a regular guy.

This poses the question: why engage in counter-signalling? One answer, analysed (pdf) by Rick Harbaugh is that "top" types do it to distinguish themselves from middling sorts. He gives the example of really bright students not boasting about their grades in order to distinguish themselves from average ones who did that sort of thing. The mega-rich who dress scruffily also do this; they are distancing themselves from arrivistes who dress expensively to flaunt their wealth. I suspect Professor Feynman also did this; he tried to distinguish himself from ordinary professors who did worry about propriety.

I suspect, though, that there are two other reasons.

One is simply that positive signals are expensive. It costs money to go to college or buy flash cars - and, in Feynman's case, signalling propriety would have meant missing out on seeing naked women. Why incur an expense if you don't need to?

The other is that a counter-signal is a selection device, used to select an audience or client base. For example, Hank Williams used his Luke the Drifter persona to signal to record buyers that some of his songs weren't juke box material. And high-end wealth management firms never advertise, because they don't want the hoi-polloi as clients.

I suspect this is what Mr Januzaj was doing. In choosing a cheap date, he was trying to select against gold-diggers and in favour of girls who might want him for himself rather than his wealth and fame; the fact that he's caught the eye of Chelsee Healey suggests he might - unusually for a Man Utd player - have got a result here. Granted, this particular date ended badly. But then, a failure to score has been the story of Man Utd's season.

Another thing: if you're wondering why I've written about a footballer's date rather than "proper" economics such as today's GDP figures then you've missed the point of this piece.

January 27, 2014

Taxes & growth

Ed Balls' proposal of a 50p top tax rate has led to talk of a "disaster" or "suicide." This is silly hyperbole.

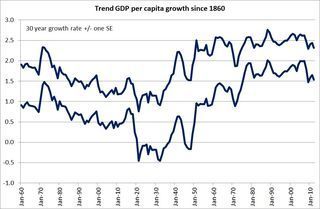

My chart shows why. It shows 30-year trend growth in GDP per capita, plus or minus a standard error. It'c clear that trend growth doesn't much change. "A bit above 1% before WWI, a bit below 2% since WWII with a lull in the interwar years" pretty much tells the story*. Growth is resilient to policy changes - perhaps because it is determined instead by technological opportunities. The idea that a tax tweak will cause disaster is historically ignorant.

To see why, let's assume that higher taxes do reduce labour supply. Let's say that the 50p rate causes Per Mertesacker (pbuh) to leave Arsenal. What happens?

Arsene Wenger does not decide to field only 10 men. He hires a replacement. The loss of GDP is therefore the difference between the BFG's salary and his replacement's. This will be small. It might even be zero; if the 50p tax rate deters footballers from coming to the UK, Arsenal will have to pay higher pre-tax salaries in which case the incidence of the top rate falls upon profits, not wages.

So, who loses in this case? The Exchequer might not; we might well be on the good side of the Laffer curve for footballers. And there's no loss of GDP - though there might be a shift from profits to wages.

Instead, the losers are Arsenal fans, who see a weakened team. But their loss is a gain for their rivals.

If the BFG isn't the only player to leave then fans generally will suffer a loss of consumer surplus from seeing worse football. If this reduces their willingness to buy tickets, football clubs will suffer. But GDP won't, as the fans spend their money elsewhere.

As go footballers, so go other employees. If the 50p tax rate causes Tesco's boss to leave, he'll be replaced. Tesco might lose from having to hire a second-rate CEO. But Tesco's loss will be Asda'sgain. And if many CEOs leave, we'll have worse-managed companies, but this might mean lower consumer surplus rather than lower GDP.

My point here is that productivity and hence earnings are properties of jobs, not individuals. If the jobs remain, any loss of income is small.

How can GDP fall, then? One possibility is that insofar as the incidence of the 50p tax falls upon profits, firms will have less motive and opportunity to invest. But this effect will be tiny. Another possibility is that the new CEOs, being second-raters, will be less able to innovate and expand. But again, this will be a small effect. And it might be non-existent, if the inferiority of the CEOs consists instead in their being less able to exploit workers effectively.

No. The way in which top taxes would reduce GDP is by either deterring entrepreneurs or driving them overseas. The former effect requires taxes to reduce effort - which might not be the case. And the latter ignores the many things that keep businesses in the UK, such as proximity to clients, a skills base or agglomeration effects. If top tax rates were important, the media would be worrying about migration to Bulgaria, with its 10% tax rate, rather than from it..

None of this is to deny that higher top taxes might have some disincentive effect - though some good work suggests they won't. It is just to note that there's no justification for talk of "disaster."

* We might note that growth was lower in the low-tax 19th century than it was in thr high-tax post-1945 period.

January 25, 2014

(Ab)uses of statistics

What's the point of the coalition's assertion that real take-home pay is rising?

I ask because voters' base their decisions not upon politicians' assertions about statistical aggregates, but upon their own individual perceptions (which of course might well be biased). Put it this way. When Ed Miliband talks of a cost of living crisis, voters might react in one of two ways. They might think he's talking rot, in which case the Tories should keep quiet on the Napoleonic principle that one should never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake. Or they might think his talk chimes with their own experience - in which case they'll not believe Tory claims to the contrary, even if these are correct on average, which is doubtful*. In the first case, the Tory claim is redundant, in the second it's implausible.

Macroeconomic data do not, and should not, over-ride individuals' local, dispersed knowledge of their personal situation.

You might think this is an Austrian point. But it is also a Keynesian one. Keynes described macro aggregates such as the price level or aggregate output as "vague and non-quantitative concepts" which are "unsatisfactory for the purposes of a causal analysis." To use a good if over-used metaphor, macro stats are only an imperfect map, not the terrain.

It does not automatically follow, however, that macro stats are useless. They could be a rough guide to policy. Targeting 2% inflation, for example, doesn't mean ensuring that prices rise 2% per year, but merely that they don't rise too much.

In this sense, Alasdair MacIntyre identified the purpose of macro stats - the claim to possess them is a claim to power: "What purport to be objectively-grounded claims function in fact as expressions of arbitrary, but disguised, will and preference" (After Virtue, p107). This sounds like a Foucauldian point, but it has been shared by people who wouldn't know Foucault from off stump. When he was Financial Secretary of Hong Kong John Cowperthwaite stopped his officials from collecting macro data** because "If I let them compute those statistics, they’ll want to use them for planning.’’

It's in this context that we should interpret the coalition's claim. They aren't talking to voters but rather to fellow members of the political class; journalists, party supporters and suchlike. The claim "incomes are rising" really means "our policies are OK." It's a claim to power.

This, though, is dangerous. If we focus upon macro data to the detriment of individuals' actual experience, we risk mistaking the map for the terrain. Which is one reason (of several) why Kenneth Boulding was right to say (pdf) that "almost all organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker."

* The claim that incomes are rising for all deciles is consistent with many people suffering a fall in income if they drop down into a lower decile. When Miliband is targeting only 35-40% of voters, this means his talk of a cost of living crisis might be good politics even if it is wrong on average.

** Strictly speaking, "data" is the wrong word. It comes from the latin for "something given", but in fact macro data aren't given at all but rather constructed.

January 24, 2014

Revenge effects

My belief that sports writing is the best form of journalism is bolstered by Ed Smith. He describes how the ideas that had improved the England team in recent years "were taken to counterproductive extremes" with the result that good players "become bad versions of their old selves."

What he's describing here is a fascinating mechanism - the idea of revenge effects. This is when a good policy has unanticipated adverse long-run effects that leave us worse off than before. They are a specific and grievous subset of the trivial law of unintended consequences.

There's a distinction between revenge effects and ordinary competition. It's common in sport and business for a good idea to be emulated by others, with the result that the advantage it gave its first adopter is competed away; this is the story of Moneyball. But it's rare in such case for the the first adopter to regret his innovation - which is what happens with revenge effects.

So, how common are such effects? David Swenson has compiled a great list. I'd highlight some others.

One is the overconfidence effect. Success can embolden us to take more risks, which can cause us to lose money. This can afflict individual investors, but also whole companies. For example, RBS's successful takeover of Nat West encouraged Fred Goodwin to take over ABN Amro, with catastrophic effects.

A variant of this is Minsky's financial instability hypothesis.This says that a period of economic stability will encourage people to take on more risk, which ultimately causes a financial crisis.

Another type of revenge effect is the efficiency wage hypothesis. This says that wage cuts will reduce productivity and increase staff turnover, more than offsetting the firm's benefit of lower wage costs.

Another mechanism through which revenge effects can work is long-run cultural change. Right-wingers who claim the welfare state has created a "dependency culture", left-wingers who complain that neoliberalism has created selfish individualism or anti-managerialists who claim that hierarchy demotivates workers are all telling stories of revenge effects.

Now, if take the idea of revenge effects to an extreme, we might end up with a John Gray-style scepticism about the very possibility of progress. This goes too far. Instead, I say all this to make two other points.

One is that the mere existence of revenge effects reminds us not only that our powers of foresight are very limited, but also that this lack can have nasty effects.

Secondly, there's an Elsterian point here. The social sciences are an inventory of mechanisms. A revenge effect is one such mechanism. The question - as for all social science is - when, where and how does such a mechanism operate? This can often only be answered with hindight. But then, nobody seriously thinks the social sciences are about forecasting, do they?

January 23, 2014

The myth of perfectibility

As a Marxist, I'm supposed to be a woolly-brained utopian whilst centrists are hard-headed realists. However, three things this morning make me suspect the opposite is the case: the Today programme's discussion of the disturbance at Oakwood prison; reports that more people die of heart attacks in the UK than Sweden; and news that NHS waiting time data are unreliable.

These stories seem to be framed as if they were deplorable departures from a norm of perfect organization. My reaction, however, is different. I remember Adam Smith's line - that there is a great deal of ruin in a nation. Any large organization will naturally contain some failures. There are, at least, two reasons for this.

One is the existence of trade-offs. Maybe prisons could prevent riots by being better staffed. But this would be expensive, and would trigger reports of "scandal of idle prison officers." Likewise, it would be expensive for the NHS to emulate best practice around the world, and efforts to do so would lead to headlines: "fury at NHS bosses free holidays". If you want lowish-cost public services, you must accept some imperfections.

One overlooked trade-off here is between efficiency improvements and consistency. Improvements - in hospitals and schools as in business - require experiments, to discover what works and what doesn't. But this would lead to complaints either about "postcode lotteries" (where successful methods aren't immediately available nationally) or about failing schools, where experiments don't work. You can avoid these problems by avoiding experiments - but the resulting consistency will be a mediocre one.

A second problem is bounded knowledge; management simply cannot know everything. It cannot predict where there'll be riots, as these are a classic case of emergent behaviour, and it is vulnerable to underlings manipulating data.

Sometimes, these two problems interact. For example, social workers cannot tell with 100% accuracy which children are in grave danger and which aren't. They must therefore choose between two errors: leaving children with parents where they might be mistreated; or breaking up families unnecessarily. Whichever they do risks the anger of the media mob - even though occasional errors are inevitable.

I stress that these failings are entirely compatible with hierarchic organization working in many/most cases. My point is merely that the best organizations are inevitably inherently imperfect and prone to error. We should not pretend - as the media (and bosses!) do - that management can be perfect and so failures could be eliminated if only people were smart enough; the outcome and hindsight biases, of course, contribute to this myth of perfectibility.

This myth, though, has pernicious effects. It encourages the belief that there can be a few heroic "leaders" who can achieve such perfectibility and who therefore deserve multi-million pound salaries and disproportionate esteem. If instead we saw small-scale failures as inevitable, we might be less inclined to pay big money for a job that cannot be done.

In saying all this I'm not making a Marxian point: my influences here are Smith, Berlin, Hayek and Oakeshott. It's insufficiently realized that scepticism about the powers of management isn't a Marxian view but rather a properly liberal-conservative one.

January 22, 2014

Who needs productivity?

"Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run it is almost everything." If Paul Krugman's famous saying is right, the UK economy is in trouble because today's figures show that total hours worked rose by 1.1% in the last three months, which implies that output per hour is falling, and is well below its pre-recession peak. And Duncan thinks Krugman is right:

Unless we see a pick-up in productivity growth soon then the UK risks much slower growth, and lower living standards, in the future.

But could it be that they are both wrong, and that stagnant productivity and decent output growth are compatible for at least a few more years?

To see my point, consider the standard story about why productivity matters. This says that if there's no productivity growth, output growth requires more employment and this higher demand for labour will raise wage growth. This will lead either to higher price inflation and hence higher interest rates or to a profit squeeze. Either higher rates or a profit squeeze would reduce firms' motives to expand and so kill off growth. Sustainable output growth thus requires productivity growth.

But there's something wrong with this story. As Jon Philpott points out, wage inflation has so far not risen at all in response to falling unemployment. There are several reasons why this might be, which might continue to hold down wages:

- Unemployment is higher than the jobless count suggests, implying that there's much more pent-up supply of labour. If we add to the unemployment count the inactive wanting work and part-timers wanting full-time work, there are still over six million people unemployed or under-employed. And even if employment grows by 2% a year for the next five years, there'd still be three million jobless on this measure.

- Memories of the great recession will have a scarring effect, by making workers scared to push for higher wages.

- The mass supply of labour from the far east will continue to hold wages down (pdf).

- Pay restraint and job losses in the public sector - the OBR foresees general government employment falling by over 500,000 in the next four years - will hold down private sector wage growth.

If these factors continue, we could see more of what we've had recently - GDP growth plus jobs growth without much inflation and hence no need for higher interest rates.

This need not imply a squeeze on profits. Wage growth of one per cent and zero productivity growth implies unit wage costs of one per cent. Barring adverse commodity price shocks, this is consistent with stable profit margins at low inflation. And with output growth raising the output-capital ratio, this gives room for profit rates to grow, thus maintaining or even increasing firms's motives to invest.

Granted, this story implies a fall in real wages for those in work. But this is offset by rising incomes as other move into work. In the year to Q3, real disposable incomes rose despite falling real wages, in part because of rising employment.

There is, of course, a lot that could go wrong with this scenario, and I'm not sure I believe it myself - though you shouldn't give a damn what I believe.But there's one thing that lends it a little credence.It's that some research has found that the link between output growth and productivity growth even over longish periods isn't as strong as you might think.

So, perhaps we should consider the possibility that we'll see continued stagnant productivity and output growth for a few more years. This would imply that the wage squeeze will continue even as unemployment falls.

January 21, 2014

Democracy & dissonance

I fear this piece by John McDonnell highlights a sort of cognitive dissonance which is common on the left.

He (rightly) bemoans the "debased politics" of hostility to migrants and benefit claimants, but seems to think the answer is a "People's parliament", in which parliament is more open to meetings of ordinary" folk.

This misses something - that the public supports caps (pdf) on migration and welfare spending; for example, in a recent YouGov poll (pdf), only 15% said welfare benefits should be protected from further cuts.

"Debased politics", then, doesn't represent a failure of democracy but rather the triumph of it. The problem with politics is not that politicians are out of touch with voters - but that they are too much in touch.

And this is where cognitive dissonance enters. Some of the left can't see that their cherished beliefs - in democracy and in income equality and tolerance - are incongruent. Rather than acknowledge this conflict, people like Mr McDonnell seem to want to try and dodge it, by hoping that a different form of democracy will somehow produce healthier attitudes.

This is theoretically possible; maybe some forms of deliberative democracy will cause prejudice to be eroded by contact with facts - but this is not assured, and Mr McDonnell gives us no reason to suppose it will happen. Indeed, research suggests that exposure to evidence that opposes our beliefs can merely cause us to entrench (pdf) our beliefs still further.

What the non-Marxian left is missing here is that capitalism sustains itself in part by generating cognitive biases - ideology - which serve to support the existing order and oppose egalitarian policies. In other words, there is a conflict between (capitalist?) democracy and justice.

Although this seems - and is - Marxian, it leads to a conclusion most associated with Isaiah Berlin:

Some among the great goods cannot live together. That is a conceptual truth. We are doomed to choose, and every choice may entail an irreparable loss. (“The pursuit of the ideal", p11 in The Proper Study of Mankind)

January 20, 2014

Market trade-offs

Ed Miliband's promise to introduce more competition into banking has faced some intelligent criticism. But it also raises some fundamental tradeoffs we face in thinking about states and markets. These are:

1. Shareholder value vs a vibrant market. Jonathan points out that the fall in bank shares after Miliband's speech is just what we'd expect to see as investors anticipate lower monopoly profits. This highlights the fact that a truly healthy market is not good for shareholders, simply because it means that profits are low and risky. If you want to see a well-functioning market, look at the fruit and veg traders on Leicester market. None of them goes home in a Bentley. For this reason, any attempt to introduce genuine competition will be resisted by fierce lobbying.

2. Anti-statism vs pro-markets. Miliband's call for state action to increase competition isn't as paradoxical as it seems. It's consistent with Polanyi's claim that the emergence of a market economy requires all sorts of state interventions. Insofar as this is the case, supporters of a free market economy cannot be anti-statist.

Of course, this view has its critics. It's possible that, in the long-run, bank competition will be increased by market developments such as alternative currencies and P2P lending. And Eamonn Butler claims that deregulation would increase bank competition.

I agree, up to a point; red tape often favours incumbents and deters entry. But I suspect that even in a dereglated industry, entry into banking would be difficult simply because of high capital requirements and the need for goodwill and brand power to induce depositors to trust the new entrant.

3. Competition vs stability. Joseph Schumpeter noted that competition "incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure" and unleashes a "perennial gale of creative destruction". A truly competitive banking system would be an unstable one, with some banks collapsing. This is not a bug, but a feature; productivity increases precisely because (pdf) firms exit the industry.

This, though, poses the question: do we really have the systems in place that would allow majorish high street lenders to go bust without seriously adverse effects upon lending and confidence? Does Miliband really want to test this?

This point generalizes. Schumpeter was, of course, not the first to note the instability of a competitive economy.94 years earlier, some guys wrote:

Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.

Which brings me to a fourth trade-off - that between a market economy and old-style conservatism. The Oakeshottian conservative, who is averse (pdf) to change, should see much to fear in a truly dynamic market economy. There are - as Polanyi recognized - strong reasons why most advanced societies have retreated from free market economics.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers