Chris Dillow's Blog, page 133

January 18, 2014

Paul Krugman & the nature of economics

Paul Krugman is being accused of hypocrisy for calling for an extension of unemployment benefits when one of his textbooks says "Generous unemployment benefits can increase both structural and frictional unemployment." I think he can be rescued from this charge, if we recognize that economics is not like (some conceptions of) the natural sciences, in that its theories are not universally applicable but rather of only local and temporal validity.

What I mean is that "textbook Krugman" is right in normal times when aggregate demand is highish. In such circumstances, giving people an incentive to find work through lower unemployment benefits can reduce frictional unemployment (the coexistence of vacancies and joblessness) and so increase output and reduce inflation.

But these might well not be normal times.It could well be be that demand for labour is unusually weak; low wage inflation and employment-population ratios suggest as much. In this world, the priority is not so much to reduce frictional unemployment as to reduce "Keynesian unemployment". And increased unemployment benefits - insofar as they are a fiscal expansion - might do this. When "columnist Krugman" says that "enhanced [unemployment insurance] actually creates jobs when the economy is depressed", the emphasis must be upon the last five words.

Indeed, incentivizing people to find work when it is not (so much) available might be worse than pointless. Cutting unemployment benefits might incentivize people to turn to crime rather than legitimate work.

So, it could be that "columnist Krugman" and "textbook Krugman" are both right, but they are describing different states of the world - and different facts require different models; I fear that Krugman's excessively combatative style is ill-judged in this context.

The question to ask of any model or theory isn't merely: is it internally coherent? It's: does it apply here and now? Here are three other examples of this:

- You can write some sort of model in which QE is deflationary. The question is: does that model apply to the economy today?

- Brad De Long has suggested that the "liquidationist" (pdf) theory of recessions - the idea that unprofiatable capital must be destroyed - was a terrible idea during the Great Depression of the 30s, but valid for some previous recessions. Different times require different theories.

- The idea of expansionary fiscal contraction might have applied in some times and places, but it hasn't applied to the UK recently.

My point here generalizes, I think. In the social sciences, very many hypotheses, models or theories are true of some times, some places and some people. One job of the social scientist is to judge which theory works when. We don't need theories of everything. We need theories of here and now.

Another thing: economic efficiency isn't the only relevant value here. There's also the principle of luck egalitarianism, which says we shouldn't penalize people for things thery can't control. This argues more more generous unemployment pay in hard times, as it's more likely in such circumstances that people are out of work through no fault of their own.

January 16, 2014

Inherently biased journalism

Lefties are getting het up about the portrayal of benefit recipients in Channel 4's Benefits Street. I fear, though, that everyone is missing a point here - that even good current affairs programming is biased.

I don't say this because of any conspiracy theory, but rather because there's a disjoint between human interest stories and the truth.

Let's start from a basic fact - that in the social sciences, pretty much anything is true sometimes. A lot of political debate is therefore about quantifiers: do we mean a few, some, most or what? Social phenomena lie on a curve; the question is: what shape is that curve? Sure, some benefit recipients are "scroungers", but some are folk who've paid in all their lives and suffered bad luck. The question is: what are their respective numbers?

This, though, is a matter of statistics. But stats are dry and boring, and never as memorable as good human interest stories; Tim Harford tries heroically to rectify this, but I suspect his audience is small. This is why the public are horribly wrong about basic social statistics.

Good TV programmes, though, are about human interest, not lectures in statistics. And this means even good programmes can be misleading. Channel 4 might think it fair and balanced to show a "scrounger" alongside a "deserving" recipient - but doing so isn't so balanced if the latter outnumber the former 10 to one. There are a couple of other dangerous biases involved too:

- If the scrounger is a charismatic figure, he'll loom larger in our memories than a less charismatic "deserving" person. The availablity heuristic will then lead us to over-estimate the number of "scroungers".

- We get more angry about injustices inflicted upon us than upon other people. Seeing a scrounger thus makes us angrier than seeing a genuine victim of poverty, and this too leaves a more vivid impression. (The issue here isn't the financial cost of "scrounging" which is small, but rather the sense that a norm of reciprocity is being violated).

However, there is nothing odd about what Channel 4 is doing here. There are numerous other ways in which the news and current affairs reporting can warp our perspectives.

- "Woman murdered" is news, "60 million not murdered" is truth. Reporting can thus increase the fear of crime beyond what its prevalence deserves.

- "Hundreds killed in factory collapse is news", "tens of thousands killed by poverty is not. The benefits of industrialization and globalization are thus under-weighted.

- In reflecting political opinion, journalism helps to maintain the Overton window by excluding reasonable but minority views. How often do you hear market socialist or genuinely libertarian/anarchist ideas?

- "Row", "split", "clash", "crisis" are journalese. Mild disagreement and indifference are not. The significance of most events is thus exaggerated.

- The mere act of communicating with someone encourages them to become more generous towards us. The fact that empty suits are always on the TV and radio thus generates sympathy towards them, whilst the exclusion of the poor from the media encourages hard-heartedness towards them.

My point here is a simple one. You cannot reasonably expect the media to promote the truth, so we should not base our political opinions upon news and current affairs programmes. Lefties should regard the media not as a reason for anger, but rather as an illustration of the subtle ways in which ideology is propagated.

January 15, 2014

Bonuses & arms races

There's an important economic principle behind the debate about bankers' bonuses. It's that individual self-interest sometimes conflicts with the collective interest.

What I mean is that it might well be rational for RBS to want to pay its bankers more to attract and retain good staff*. But the benefits to RBS of employing such people come at the expense of other banks. The star M&A banker wins business at the expense of rival banks; the good trader makes profits at other banks' expense and so on.

But what's true of RBS is true for any other bank. Each must offer big money to retain staff, the result of which is that aggregate banking profits are lower than they'd otherwise be. And over time, this means banks build up less capital than they would otherwise, with the result that the banking system as a whole is riskier than it'd otherwise be.

Banks are therefore engaged in a form of arms race. Just as if two rival nations compete to have the bigger military, the upshot will be that both are impoverished without any offsetting benefit, so banks are impoverished by high salaries.

There are several other examples of arms races, some of which are described by Robert Frank and Tom Slee, for example:

- Any individual might want to work longer than his colleagues to increase his chances of promotion. But if everyone does so, they all end up working longer than they'd like (pdf), without any improvement in their prospects for advancement.

- If people spend money to keep up with the Joneses - and they do - the aggregate result can be more debt and financial fragility without any rise in well-being.

- If education has a signalling benefit (it does), then each individual will feel the need to become at least as well credentialled as his peers. The result will be increased numbers getting degrees, but with a rising mountain of debt rather than an improvement in aggregate job prospects.

What we have in these cases is a form of market failure - because what's rational for any individual is collectively self-defeating. There is, therefore, a case in principle for government action to restrain pay. Hence the EU's bonus cap**.

In this context, the government has a dilemma; policies which might maximize RBS's value - paying to get the "best people" - might merely exacerbate collectively harmful behaviour.

I don't pretend to have any easy answer to these issues. I merely note that the issue of bankers bonuses falls into a set of behaviours which contradict the invisible hand theorem: the pursuit of self-interest does not always increase the collective good.

* It's also possible that bonuses have adverse incentives for the individual bank. For the purposes of my story, I'm ignoring this.

** Whether such caps work or not is another matter. Capping bonuses might lead to higher base salaries, and capping salaries might lead to more non-cash rewards such as company jets, prostitutes and yachts.

January 14, 2014

The immigration curve

What is the distribution of the impact of immigration? I ask because there's tendency to discuss immigration only in terms of average effects - the average being slightly positive (pdf) (in economic terms) if you're (pdf) in the reality-based community and negative if you're not.

This discourse, however, misses something - that there's a distribution around any average. Consider each particular immigrant. His effect on British society might be heavily negative (if he's a serious criminal), slightly positive (if he's a typical worker), or hugely positive - if he's a brilliant entrepreneur, scientist or sportsman.

We should, therefore, think of an "immigration curve", with a few serious criminals at one extreme, a mass of ordinary folk around the middle and a few great benefactors at the other. (I stress that I'm not thinking in narrow economic terms here - the benefits and losses are cultural as well.)

But here's the thing. There's no reason to suppose that this curve is bell-shaped.Quite the opposite. It's more likely to be positively skewed. There's a limit to the amount of cultural and economic damage an immigrant criminal can do - unless he gets to run a bank or football club. But the upside gains from a great migrant are potentially vast. The gains we make from getting an Andre Geim, Elias Canetti*, Ola Jordan, Wojciech Szczesny**, Friedrich Hayek, Michael Marks or Mo Farah - to name but a handful - offset a lot of petty criminals.

Thinking of an "immigration curve" helps explain why attitudes to migration differ:

- The more you believe a few great people can tranform society, the more you should favour free migration, as it raises our odds of attracting such people. Randians who believe in heroic entrepreneurs, or economists who think that socio-technical change is increasing the significance of superstars should therefore favour open borders - because that right tail of big contributors is a fat one.

- Hayekians, who doubt that governments have the knowhow to exclude "bad" immigrants and admit "good" ones, will favour more open borders.

- People of a conservative disposition - Oakeshottians (pdf) whose instinct is to regard change as deprivation - will oppose immigration, as they put less weight upon the small chance of a large upside, and worry more about the larger chance of loss.

- People who are more open to new experiences will favour migration, as they put more weight than conservatives upon the potential upside. It could be that liberals favour freer migration because liberal political views are correlated (pdf) with psychological openness.

- People who are in a position to reap the cultural rewards that a tiny minority of migrants bring will be more supportive of open borders than those who aren't. If you appreciate the work of Peter Medawar or V.S. Naipaul you're more likely to be pro-immigration than you are if your experience is confined to hearing disconcerting languages on the bus.

Herein, though, lies a problem. We know from behavioural finance that our thinking about probability distributions is clouded by numerous cognitive biases. It could be, therefore, that we all misperceive the shape of the immigration curve - including me.

* Is it just me, or is Auto da Fe one of the best novels ever written?

** You might object that Szczesny is a source of disutility for Sp*rs fans. But when Jeremy Bentham said that in measuring utility everybody should count for one and nobody for more than one, he didn't have Sp*rs fans in mind.

January 9, 2014

Tories & the minimum wage

Is it right to impose misery upon a few so that many people can gain? This ancient ethical question is raised by reports that the Tories are considering an above-inflation rise in the minimum wage.

I don't think this is motivated by a conversion to a Card-Krueger style belief that demand curves don't slope down (and nor perhaps should it be), or to the merits of wage-led growth. If this were so, there'd not be much left of conventional Tory economic thinking.

Instead, the justification for hiking the minimum wage could be the belief that the wage gains to the many more than offset the job losses suffered by a few.

To get a rough feel for how this is possible, let's use some estimates by Nattavudh Powdthavee*. He's calculated that a 1% rise in income raises well-being by 0.019 points, on a 1-7 scale. (I'm taking the fixed effects results in table 1).

If we take 100 minimum wage workers, you might think this means a 10% rise in the minimum wage would raise "utility" by 19 points - 10 x 0.019 x 100. You'd be wrong, because the higher minimum wage would trigger reductions in tax credits and other benefits. If we assume a withdrawal rate of 50%, we get a utility gain of 9.5 points.

Now, Professor Powdthavee also estimates that unemployment reduces well-being by 0.289 points. This implies that if fewer than 32 workers lose their jobs, then our 100 low-wage workers are, in aggregate, better off as a result.

This is plausible; it's unlikely that the price elasticity of demand for labour is as high as 3.2.

So, hiking the minimum wage is justified on utilitarian grounds, right?

Wrong. Higher wages for minimum wage-workers come out of employers' pockets, so they suffer a loss of utility. What's more, because higher minimum wages go party to the Treasury, their income loss isn't fully offset by workers' gains.

You might justify this by an empirical claim that the marginal utility of income is much lower for an employer than it is for an employee, or by a moral claim that low-wage workers' well-being matters more than that of employers. But I doubt a Tory would be comfortable with either.

Even if we allow for only a few job losses, therefore, it's likely that - from a Tory mindset - a minimum wage hike isn't a good utilitarian policy.

So why adopt it?

One possibility is that the public finances also enter Tories' utility function, so that a reduction in spending on tax credits becomes a good thing. This, though, is daft; in a liberal society, the state has no interests other than those of the people, so a transfer of income from employers to government can't raise utility.

The more rational possibility is that a rise in the minimum wage would steal Labour's clothes or shoot their fox - or whatever other vapid metaphor you prefer. If this is so, it means Tories are jeopardizing the (short-term) interests of some capitalists for their own advantage. Which raises interesting issues about the nature of the state in capitalist society.

* There are lots of ways you can quibble with this calculation, but I don't think doing so overturns my main points.

January 8, 2014

Lily Allen & decision theory

A tweet from Lily Allen raises some interesting economic issues:

About 5 years ago someone asked me to stream a gig live on second life for hundreds of thousands of bitcoins, 'as if' I said. #idiot #idiot.

This reminds us that tail risk - the small chance of extreme outcomes - isn't just on the downside. It's also on the upside. Which raises the question: is it wise to chase such upside risk, as Nassim Nicholas Taleb advises in The Black Swan?

Sometimes, the answer's yes: getting out and going to parties exposes us to the small chance of meeting someone who'll greatly enrich our lives. But sometimes, the answer's no. In stock markets, stocks with the small chance of big gains are overpriced on average; this is one reason why the Aim has under-performed for so long.

I suspect that Ms Allen's case falls near the latter camp. Anyone who's in the public eye gets hundreds of requests from timewasters, twats and parasites who won't pay for their time in proper money. The only way Ms Allen could have accepted the Bitcoin offer would have been to accept countless other idiot proposals. But this would have left her exhausted and poorer as she neglected proper paying work.

In this sense, there's a big difference between judging actions ex ante and ex post - between being rational and being right. Ms Allen was rational to reject the gig, even though she now feels she wasn't right to do so.

Which raises the issue of regret. The cost of that rejection is the regret at not getting the £60m+ she would have made had she accepted and kept the Bitcoins.

However, it's curious that Ms Allen should single this out for regret. Why doesn't she regret, for example, not buying ASOS shares when they were under £2, or countless other missed oportunities?

Every choice we make (or don't) closes off some opportunities; all choice carries an opportunity cost. We could therefore spend our lives regretting the countless shares we might have bought when they were dirt cheap, the horses we didn't back, the job offers we might have accepted, the partners we might have met had we bothered to go to that party, and so on. But if we did this, we'd just be crippled with remorse.

There's a good reason and a bad reason why we're not. The bad reason lies in a variant of the availability heuristic. Often, we don't see where the road not taken would lead, so its costs and benefits aren't available to us - and out of sight is out of mind. This heuristic, I suspect, explains why Ms Allen should single out rejecting that gig; its costs are now salient, which is unusual for a rejected option.

The good reason for not regretting so many choices is that we should ask not "was this action right?" but rather "was the rule which led me to this act rational?" For example, I don't regret missing out on shares whose prices have soared because I follow the rule "be a passive investor" - a rule which is if not optimal then at least reasonable. Likewise, the rule "reject offers from timewasters" was a rational one for Ms Allen, even though it was wrong in this one instance.

There is a point to all this. Economics is not (just) about bigthink or futurology or policy. It's about the choices we all make everyday. And this means that sometimes we can learn more from a celebrity tweet than we can from the pratings of pompous empty suits.

January 7, 2014

On forecast-based policy

There's one particular line in Osborne's speech yesterday that irritated me. It's this:

On the Treasury’s current forecasts, £12 billion of further welfare cuts are needed in the first two years of next Parliament.

Now, there is one fact about the Treasury's forecasts that is more important than any other.

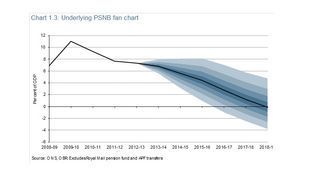

It's that they are wrong. The OBR has estimated that the standard error in PSNB forecasts three years out is 3.2 percentage points of GDP (table 2.2 of this pdf). One interpretation of this is that, given a forecast for PSNB of 2.7% of GDP in 2016-17, there's a roughly one-in-five chance of the actually government running a surplus then. The point about fiscal fan charts is that the fans are wide.

One reasonable principle of decision-making is that policies should not be based heavily upon a forecast with such huge error margins. The investor who bases his asset allocation upon an economic forecast, or the CEO who makes a big investment on the basis of one, are both being prats.

Yes, monetary policy is (sometimes) set on the basis of a forecast. But QE and interest rate changes are easily reversible if the forecasts turn out wrong. The same cannot be said of the benefit cuts Osborne has in mind.

Let's put this another way. In what circumstances is it likely that government borrowing will be high in 2017? To see them, remember what Mr Osborne doesn't seem to know - that the nation's finances are not the same as the government's. A government deficit, by definition, means that other sectors are running financial surpluses. This means some combination of three things: households are net savers, say because they want to repair their balance sheets; the corporate sector is investing less than its retained profits; and/or the rest of the world wants to be net savers - which implies weak overseas demand.

These circumstances will be ones in which the economy is weak and jobs scarce - which means that people will, through no fault of their own, find it difficult to move off benefits. And this is exactly the time in which benefits should not be cut. If anything, the time to cut benefits is precisely when cuts are not "needed" - when the public finances are healthy because the economy is booming.

Now, in saying this, I'm not arguing against benefit cuts per se. If you must argue for them, do so on grounds of claims about existing facts - such their possible disincentive effects - and not on the basis of the fictions which people call forecasts.

January 6, 2014

Rising pensions: who gains?

David Cameron's proposed "triple lock" on pensions is widely regarded as an attempt to bribe the powerful grey vote whilst ignoring younger folk. This is questionable.

From one perspective, the exact opposite is the case. Rising pensions are better for youngster than oldsters. This is simply because they can look forward to many years of rises, whilst an old person will probably die after only a few years of getting them. If you're 40 years shy of pension age*, a 0.5% annual real rise in the state pension increases the value of your retirement wealth by over 25%. This is much more than an 80-year-old will get, who can anticipate only eight years of rising pensions before he dies.

Why, then, does everyone think a rising pension is a bribe to oldies rather than youngsters?

One possibility is that Cameron's pledge is unaffordable and so it'll be reversed before 20-somethings retire. This, though, is doubtful; long-run forecasts for the public finances are subject to considerable uncertainty. And those who see the promise as a bribe aren't arguing that it is merely temporary.

Another possibility is that we discount the future, and so a higher pension is less valuable to youngsters than it is to older folk. However, long-term interest rates are close to zero. Even if we add to this the probability of death, which is less than 0.5% per year for the under-50s, we still have a low time-discount rate - so low that it could be that pension growth outstrips the discount rate, which would mean youngsters benefit more than oldsters from rising pensions.

Why, then, does everyone seem to take for granted that rising pensions are better for the old than young?

One possibility is that there's a bubble in gilts, which means that gilt yields are no guide to people's actual rate of time preference. Another possibility is that young people are risk-averse, and attach more weight to the risk of dying before pension age than life tables suggest. A third possibility is that Cameron's pledge carries a cost of higher taxes, and these will be borne by today's (and tommorow's) working people rather than by today's pensioners. In this sense, pensioners are getting something for nothing, whereas younger people are paying for their higher future pensions; oddly, though, nobody has translated Cameron's pensions pledge to mean "higher taxes on working-age people."

There is, though, a fourth possibility. It's that the commentariat believes (rightly or wrongly) that young people have very high time discount rates - say because of hyperbolic discounting or some other form of present bias - and so just don't appreciate that rising pensions will benefit them.

I'm not sure which of these is right; they might all be to some degree. My point, though, is simply that the kneejerk view that rising pensions are a bribe to the elderly requires some anciallary assumptions to hold if it is to be correct.

* Yes, the pension age will rise over time, but it's not obvious that Cameron's announcement yesterday represents any new news on this front.

Another thing: altruism complicates things a lot; I'm assuming it away.

January 3, 2014

Truth vs power

To everyone's complete unsurprise, newly-released Cabinet papers show that Arthur Scargill was right to claim during the miners' strike that the government planned to close many more pits than they were claiming in public. This is not the only way in which subsequent events have vindicated the miners. Jobs lost to pit closures have not (pdf) been fully replaced, suggesting that the slogan "coal not dole" did indeed make economic sense.

Scargill, then, had truth on his side. And what good did it do him?

Bugger all. He lost.

There's a message here that's still relevant today - that, in politics, power matters more than truth.Take just three examples:

- When Jonathan Portes tried to introduce some facts into the immigration debate, the BBC's Nick Robinson replied that "he would not have a chance of getting elected in a single constituency in the country".

- Iain Duncan Smith has repeatedly mangled the truth. But he has power and his more truthful critics don't.

- Critics of fiscal austerity were right. But for reasons which aren't entirely admirable, this fact isn't sufficiently recognised. Again, power wins. As Simon says: "the politicians want to go in the opposite direction to the one suggested by the economics."

You might think that post-truth politics is to be deplored. I fear, though, that such an attitude is little naive. To think that the truth should matter in politics is to commit a category error; politics is about power, not truth - and truth matters only to the questionable extent that it is a basis for a claim to power. Intellectuals' belief in the primacy of truth is an example of deformation professionelle - the tendency to believe that the values of one's own profession should apply more widely than they do.

I'm not sure the answer here is to fight lies with lies: the untruths of the powerless don't stand a chance against the untruths of the powerful. My inclination instead is to sympathize with Alasdair MacIntyre:

The barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. (After Virtue, p263)

Note for the hard of thinking: I'm not claiming here that the truth lies solely on the left. Immigration is not (or at least shouldn't be) a left-right issue. And on some matters - such as the denial about the incidence of corporation tax - many leftists are wrong and rightists are right. And I'd even concede that the rightist aim of shrinking the state isn't incompatible with the evidence.

January 2, 2014

The outcome bias

The FT reports that a plurality of economists believe that the UK's return to growth vindicates Osborne's austerity policies. This reminds me of a lot of football reporting, in that it seems an example of the outcome bias - the tendency to assess behaviour by results rather than by the quality of that behaviour.

In football, this bias takes the form of judging teams' play by the final score and downplaying the fact that the result was affected by luck. So, for example, Liverpool and Arsenal are deemed to have been poor because they failed to beat Man City and Chelsea - despite the fact that these failures were due in part to some dubious officiating*.

Similarly, the fact that the economy is now growing makes Osborne's fiscal policy look good.

This, though, is wrong. As Tony and Simon have said, a belated return to growth is entirely consistent with the orthodox Keynesian theory that austerity depresses output. To give Osborne credit for the recovery is like praising a taxi-driver for getting us home when he has taken us on a two-hour detour.

Instead, what we should be doing is blaming him for the detour. The belief that austerity would lead to decent growth was an unscientific one - simply a bad decision. The fact that the economy is now growing does not alter this fact, any more than a refeering error should alter our assessment of a team's quality.

My point here is not simply to rehash what Simon and Tony say better than I could. Instead, it's to point out that cognitive biases are ubiquitous. The same sort of error that causes us to misinterpret football games also causes us to misread the economy. The front halves of newspapers are as warped by irrationality as the back halves.

* The fact that the bad decisions favoured teams owned by multi-billionaires is of course mere coincidence.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers