Chris Dillow's Blog, page 137

November 9, 2013

Is conservatism dead?

Whatever happened to good, genuine conservatism? I'm prompted to ask by a post by Ben Cobley. He says that a debate about immigration which focuses only upon economics misses the point - that immigration also matters because it challenges our sense of home and community.

In this, Ben is echoing Oakeshott (pdf):

To be conservative...is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried...Familiar relationships and loyalties will be prefered to the alure of more profitable attachments...Change is a threat to identity, and every change in an emblem of extinction.

Such a sentiment isn't wholly absurd. There's some - albeit mixed (pdf) - evidence that immigration (pdf) can undermine some types of social capital, at least in the short-run and when it occurs against a background of deprivation (pdf) and inequality.

However, the most vocal Tory critics of immigration don't seem to take this Oakeshottian communitarian line. Instead, they seem to prefer to challenge the economic evidence which shows (pdf) that immigration is - for the most part - a net (pdf) economic benefit.

The contrast between these two lines is stark. To attack the economic evidence is to be shrill and anti-scientific, whereas the Oakeshottian disposition is cool, wistful and melancholic.

And here's the paradox. Oakeshottian sentiments are, I suspect, far more common on the left than the right. Elegies for lost working-class communities, for example, are more Oakeshottian than much of what we hear on the right, and Ben himself is writing from a leftist perspective.

Hence my question: why did the conservative dispostion fade on the right?

Perhaps it hasn't, and I'm a victim of the selection bias: shrill overconfident hysteria makes itself heard above quiet melancholia - a process amplified by the media selecting voices for controversy rather than truth-value.

If it has, what went wrong? I would blame - but then I would! - the capture of the Tory party by managerialists and the rise of an egomaniac culture which prefers to parade overconfident ignorance rather than gentle scepticism.

Whatever the reason, Ben's lament about the state of the immigration debate tells us something not just about immigration but about the decline of a reasonable and sometimes valuable sentiment.

November 8, 2013

On (rational) expectations

Reading Simon's defence of rational expectations made me wonder: what's the empirical evidence here?

One obvious data source is the Bank's survey of households attitudes to inflation. Every three months it asks people what they think the inflation rate has been in the last 12 months, and what they think it'll be in the next 12. My chart shows the median answers to these two questions.

It's clear that there's a close link between the two; the simple correlation coefficient since data began in 1999 is 0.88. Regressing inflation expectations upon current inflation gives us the equation: 0.87 + 0.6 x past inflation. Whilst this might be consistent with some rational expectations, it's also consistent with a simple rule of thumb: expect inflation to be what it is now, but adjust down if inflation is unusually high, and up if it's unusually low.

This in turn is consistent with Paul Ormerod's claim (pdf) that we should model behaviour as if agents used rules of thumb rather than full maximization.

So, is Simon wrong? Not necessarily. Look what happened in the recession. Inflation expectations then were lower than you'd expect from this rule of thumb. In exceptional circumstances, then - by which I mean the cases of most interest - agents form expectations in some other way.

How? Rational expectations are certainly one possibility. Another (non-exclusive) possibility is that, as Chris Carroll has described, expectations spread in much the same way diseases do: if enough people have (say) low expectations for inflation, they'll infect others.

This leaves me in an awkward position. On the one hand, agents sometimes (often) seem to have what Simon calls "naive" expectations. But on the other, they don't always have them.

Which brings me to something I've said before - that we should think not just about models, but mechanisms. We should ask: what is the mechanism by which inflation expectations are formed? It is perhaps reasonable to suspect that in ordinary times, the mechanism is a backward-looking rule of thumb. After all, in stable times, folk have better things to do than think about inflation. In abnormal times, however - such as recessions or high inflation - the costs of being wrong about inflation become higher, which leads people to abandon rules of thumb in favour of something else.

Now, this is much easier said than modeled; it leads us into Markov-switching models and other stuff I don't understand. And it might not be much use for forecasting purposes: can we tell in advance whether the expectations formation process will shift? Maybe the real world is more complicated - nay, complex - than any single model would suggest.

November 7, 2013

Unavoidable failure

I recently wrote that one of the lazy assumptions of the political-media class is the belief in perfectibility and inability to see that failure is very common. Since writing that, we've seen two examples of what I mean: reports that the cost of two new aircraft carriers is double its initial estimate; and the PAC's claim that the implementation of the new universal credit has been "extraordinarily poor".

Such episodes confirm my prior, that mismanagement of big projects should be regarded as the norm and success as the exception. This is simply because such things are more complex than any single individual can possibly manage; bounded knowledge isn't an individual weakness to be deprecated but rather an ineliminable fact about the human condition.

Our inability to see this leads to the planning fallacy. Imagine that, for a project to come in on time and on budget, 50 separate elements must come together, and imagine that each has a probability of success of 98%. Basic maths then tells us that the probability of the project succeeding is only 36.4%. Sadly, though, many politicians don't know basic maths.

You might think that this just shows us how inefficient the public sector is - which is only to be expected given that incentives are weak and departments are run by the sort of people who give mediocrity a bad name.

I fear, though, that this is too glib.As Paul Ormerod has said (pdf), "failure is pervasive" in the private sector too, and for the same reason - that managers' ability to know enough is severely limited (pdf). For example, around 10% of firms cease trading every year, which means that the chances of long-term survival are very slim.

And bosses are like politicians in at least two respects; they too misunderstand the basic maths which warns that planning is failure-prone. And they too are selected to be overconfident about their chances of success.

Perhaps, then, politicians, journalists and the media share a common ideology - a presumption that top-down management can competently oversee complex events to a greater extent than is the case. This presumption leads then to fail to see that what makes the private sector successful - insofar as it is - is not so much the quality of management as the existence of markets. The general public might have anti-market attitudes - but so too does the ruling elite.

November 6, 2013

ignorance

Economics, it is said, is the study of scarcity. There is, however, one thing that certainly isn't scarce, but which deserves the attention of economists - ignorance. A recent paper by Richard Zeckhauser and Devjani Roy - which introduces a new method of economic research - shows that this is unjustly neglected in economics.

Conventional economics analyses how individuals choose - maybe rationally, maybe not - from a range of options. But this raises the question: how do they know what these options are? Many feasible - even optimum - options might not occur to them. This fact has some important implications.

1. It matters for labour market mismatch. If people don't know of jobs they could reasonably fill, we'll get a mix of unfilled vacancies and unemployment - a bad Beveridge curve. This is likely to be an especial problem (pdf) in recessions, when job destruction requires people to change careers.

The issue here isn't just a short-run cyclical one. Young people can be ignorant of what careers are possible, and so drift into jobs they are unsuited for whilst neglecting worthwhile options. This is why better careers advice or role models are so important.

2. It matters for investment. If folk are ignorant of the possibility of an impending crisis, they might over-invest. Equally, though, firms' ignorance of technological or market opportunities can cause them to under-invest.

It's in this context that entrepreneurship matters. An entrepreneur is someone who reduces ignorance, by finding a market or technology of which others were ignorant. The conventional economics of "max U from a range of given options" has no place for entrepreneurship. Once we put ignorance at the heart of our thinking, a place emerges.

3. Ignorance can be a corporate resource. Customers who don't know of alternative products get ripped off; potential rivals who don't know the technology or market don't enter the industry.

4. Reducing ignorance can raise long-run economic growth not just by improving labour market matches, but by raising awareness of possibilities. Robin Hanson has said that we can think of really long-run growth as a series of ever-increasing modes. But why might growth rise? One reason could be that in traditional hunter-gatherer or agricultural societies, people's small social circles made them ignorant of economic possibilities, whilst increasing networks - first through mass literacy and latterly through the web - expand people's horizons and reduce their ignorance. One could argue here that social structures and cultures which block such networks - such as presenteeism - thus serve to impede growth.

Now, I suspect (hope) that this will seem trivial to economists in the Austrian tradition, which has tended to recognise (pdf) the role of ignorance. It does, however, clash with the managerialist ideology of our time, which pretends to manage away ignorance. In a brilliant post, Will Davies gives a lovely example of this. Academics making funding applications, he says:

have to describe the entire project, its outcomes and 'impact' in advance. These pieces of science fiction serve little purpose of ensuring that money goes to the 'best' recipients, but a great purpose in reassuring the state that nothing unexpected will happen.

But the entire point of economics - and indeed of life - is that the unexpected does happen. An ideology which overlooks ignorance is therefore a fiction. And worse still, a potentially costly one.

November 5, 2013

Living Wage macroeconomics

Macro policy matters more than micro. This is one message we should take from Howard Reed's claim (pdf) that a living wage could be a net creator of jobs.

This claim rests on three assumptions, which I find questionable.

First, that "the short-run impact of reduced profits on consumer demand is zero." If this is the case, then the transfer of income from employers to employees (who are likely to spend their incomes) would boost GDP. But I'm not so sure it is. For one thing, many low-wage employers aren't giant corporations but smaller firms whose owners rely upon their profits. Secondly, expectations matter. If employers expect further rises in the living wage, and further cuts in profits, they might cut their consumer and investment spending in anticipation.

Secondly, he assumes that the £3.3bn improvement in government finances from higher tax receipts and lower benefit spending will be used to increase public spending and investment. This is an important point. Some supporters of a living wage say it will improve the public finances. Howard is entirely correct to see that this isn't a virtue of the plan, but a defect. On its own, a living wage is a fiscal tightening, which is a net destroyer of jobs.

Thirdly, Howard assumes this spending will have big multipler effects. He says: "multiplier effects are larger – and perhaps much larger – when national economies are operating well below full employment."

I agree this is the case when we're at the zero bound. However, a living wage won't be introduced until after 2015. By then, we might be moving away from the zero bound; markets expect three month rates to be 1.4 percentage points higher in September 2016 than they are now. This poses the danger that fiscal looseness could be offset by monetary tightening, implying lower multipliers and less job creation.

I don't say all this to rubbish Howard's paper. It's an excellent piece of work. I do so instead to point out that a living wage makes sense only within the context of an expansionary macroeconomic policy. Without this framework it is a threat to jobs, not (just) because higher wages might destroy jobs - Howard questions this, but I'm not so sure - but also because of that fiscal tightening implied by higher wages. And given that well-being is more sensitive to job losses than to income gains, this is a big drawback.

In fact, there's another reason why macro policy matters. As Howard points out, the biggest winners from a living wage are households in the middle of the income distribution, not those at the bottom. A living wage is not much of an anti-poverty policy. One of the best things governments could do to reduce poverty is to get more people into work. And that's a task for macro policy.

November 4, 2013

Price signals vs culture

Why don't people respond more to price signals? I'm prompted to ask by Laurie Penny's complaint at being ripped off to live in a rat-infested slum.

She's right that this is outrageous. But she seems unaware that the solution lies not with better housing policy - we'll grow old waiting for that - but in herself. Every writer must ask: what would Hunter S. Thompson do? And the great man would have legged it out of the city - though not before shooting the rat. The great thing about being a writer is that you can do the job anywhere. The answer to Laurie's problem is simply to move out of London. You can rent a four-bed house in Leicester (say) for the price of a one-bed flat in Hackney.

And of course, it's not just renters who have an incentive to move. For the price of a one-bed flat in London, you can get a detached house here in Rutland plus a few hundred thousand pounds in change. I know - I did.

In not doing this, though, Laurie is in the great majority. Latest figures show that, in the year to June 2012, a net 51,700 people moved out of London into the regions. This is only 0.6% of London's population. Which seems to me to be a tiny number in light of the massive house price gap. John says professionals and creatives are being priced out of London - but the process is an awfully slow one.

Why so slow? Of course, some people need to work in London. But I suspect these - policy wonks, City workers and suchlike - are a minority. And, yes, we must guard against the fallacy of composition here; whilst it's possible for any individual teacher (say) to move out of London, not all of them can.

Nevertheless, we have a puzzle here. I suspect a big part of the answer lies in a preference for familiarity. We know that ambiguity aversion can be a powerful force in economics, and it's close cousin, the home bias, can cause people to buy disproportionate quantities of local goods and assets. Perhaps the same thing is keeping Londoners in London - an aversion to change. (You could, of course, put a positive spin on this by calling it a preference for the social capital of one's friends.)

In this respect, of course, British culture is very different from, say, the US's. In the latter, there's a long history - captured in song and literature - of people moving hundreds of miles. Here, there isn't. The upshot is that people are slow to respond to the signals being sent by the housing market.

This illustrates a general point. Markets are not merely places where anomic rational calculating machines meet. They are instead embedded in a society and in cultural norms. And sometimes, these norms stop those markets working as well as they otherwise would.

November 3, 2013

Ten political assumptions

A commenter on a previous post suggested I compile a list of "10 lazy assumptions that are part of the mainstream political consensus." Although the point of being an amateur blogger is that I don't have to do requests, it's a fair question. Here goes. (What follows is in part a summary of recent posts).

1. Managerialism. The dominant ideology in politics is that problems are soluable from the top-down, and the answer to organizational failure in the public services is better management. This overlooks the possibilities that: management competence is limited, in part because - as Hayek said - knowledge cannot be centralized; that hierarchy has a demotivating effect upon workers; and that faith in management is an ideological front for rent-seeking.

2. Devaluing professional autonomy and ethics. The counterpart of the elevation of management is - in schools, universities and hospitals - a denigration of traditional professional standards and ethics. This denigration extends to politics. Politicians presume that they should be like businessmen, and ignore the possibility that - as Oakeshott said (pdf) - politics is itself a "specific and limited activity".

3. The myth of perfectibility. Politicians don't believe there is a great deal of ruin in a nation. Instead, their attitude to failure - be it riots, the murder of babies or cost over-runs in government IT projects - is that not that such things are inevitable in a fallen world, but that lessons must be learnt. (Of course, they never are.)

4. A faith in hydraulic policy. Politicians are selected for their belief that policy matters, and so exaggerate both the power of policy, and the differences between the main parties.

5. Ignorance of deadweight costs. Immigration controls, anti-drug laws and complicated welfare states all impose deadweight costs. Politicians underplay these.

6. A belief in the virtue of "hard work." This ignores the fact that many virtuous activities are not paid employment, and that a desire for work is futile in an era of mass unemployment.

7. The fetish of public opinion. Politicians take voters' preferences for granted, and fail to see that they might be warped by cognitive biases or adaptation to injustice. As a result, some otherwise reasonable policies - open borders, basic income, worker control - are off the agenda.

8. A partial use of cognitive biases. Cameron's "nudge unit" tells us how politicians see cognitive biases - as a lever for improving the behaviour of others. What they don't see is that their own ideas, and those of voters, might also be disotrted by cognitive biases.

9. A consensus on the size of the state. The main parties agree that government should account for around two-fifths of the economy. The possibility of either greatly expanding the role of the state through public ownership or the role of markets through macro markets or demand-revealing referenda are alike excluded. When politicians talk of bringing markets into public services, it's usually a cloak for increasing the profits of client companies.

10. A belief in government as Santa. Politicians agree that their clients - married couples or the hard-working low-paid - deserve favours whilst others (scroungers) deserve punishment. The possibility that such distinctions are very narrow and costly to make is downplayed.

I don't say all this to mean these assumptions are necessarily wrong. I do so just to point out that politcal debate is much narrower than you might think. What's more, these assumptions are shared not just by politicians but by much of the media too.

November 2, 2013

The wage problem

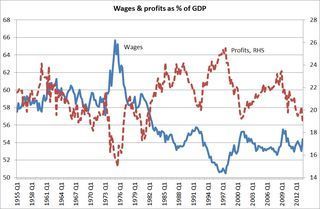

Hopi expects that Ed Miliband's speech on wages next week could say that "not enough of our national income has been going to the many." A glance at the national accounts data, however, suggests this claim is problematic.

My chart shows wage and profit shares since quarterly data began in 1955.It shows that the wage share - the proportion of national income going to the many - is now around its post-2000 average. Polly's right to say that the wage share fell "long before the crash". But it did so between 1975 and 1997. It's the profit share that is unusually low by recent standards, not the wage share.

This shouldn't be surprising. For one thing, the profit share is partially cyclical; it tends to fall in recessions and slowdowns. And for another, productivity has fallen, which suggests that one way in which capitalists exploit workers - getting them to work more intensively - has weakened in this recession.

Duncan is right to say we have a wage crisis rather than a cost of living crisis. But wages are low because the economy is weak, rather than because capitalists have been grabbing a bigger share of the cake recently.

All this said, you could still argue that the wage share is too low and the profit share too high, in two ways:

1. Any amount going to profits is unjust. This is because profits are a sign that workers are being exploited (pdf), and capitalists do nothing to justify such a return. There's good evidence, for example, that firms with external shareholders have lower capital spending, worse corporate culture and inadequate control over management.

2. Even though the profit share is quite low by recent standards, a shift in incomes from profits to wages might be a good thing, if the propensity to spend out of wages is higher than that to spend out of profits.

Claim 1 is, I fear, too radical for Miliband junior. And claim 2 is probable rather than certain.

So where does this leave us? Simple. The most obvious solution is the wage crisis isn't to shift the share of incomes - I share Hopi's scepticism about micro-interventions - but simply to increase the demand for labour through macroeconomic policy. Sadly, though, with monetary policy of dubious efficacy, looser fiscal policy ruled out - because it just is, all right? - and jobs guarantees used to harass the jobless rather than to provide an employer of last resort, such policies probably won't be equal to the scale of the task.

November 1, 2013

Marxism, socialism & technology

Rejoice! Tim Worstall has become a Marxist. He points to an example of how technology shapes people's choices of whether to cooperate or not as corroboration of Marx's claim that "The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life." He then says:

If the old philandering sponger off Engels was correct on this then should we listen to the modern leftists who insist that we should all be doing much more cooperating socially and a lot less competing...? No, absolutely not: for what is being stated is that that level of cooperation or competition is emergent from the technologies in use... Even if the old boy was correct on this point the wailings of his successors are still wrong.

Here, though, Tim wrongly conflates the Marxist and non-Marxist lefts. Sure, the non-Marxist left wants more cooperation. But we Marxists see that, within the confines of capitalism, this is happy-clappy idealizing - a bit like Hopi Sen's "yes, we'd like a free pony." Marxists know that socialism requires particular material conditions, and that if these are lacking, revolution will be premature. As Marx said:

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed.

There are two particular conditions here:

1. People must be sufficiently wealthy that they have pro-social motives. Marx saw what Ben Friedman has corroborated - that the potential for cooperation grows with income; desperate men rarely think of others. Here's Jerry Cohen:

[Marx] thought that anything short of an abundance so complete that it removes all major conflicts of interests would guarantee continued social strife, "a struggle for necessities and all the old filthy business". It was because he was so uncompromisingly pessimistic about the social consequences of anything less than limitless abundance that Marx needed to be so optimistic about the possibility of that abundance. (Self-ownership, Freedom & Equality p10-11)

2. Technologies must exist which permit cooperative modes of production, and which capitalism cannot develop.

Here, though, it is quite possible to argue that we are moving in this direction, in (at least) two ways:

- The decline of mass production and rise of more human capital-intensive businesses means that traditional capitalism with external shareholders and top-down hierarchies is no longer technically efficient. A classic paper (pdf) by Luigi Zingales discusses this in non-Marxian terms.

- The internet is facilitating cooperation at the expense of traditional capitalism. We see this most clearly in the way the media and music industries are suffering, but we could add P2P lending too.

Sure, these are small beer now. But they might grow. The socialist revolution might take as long as the industrial revolution.

But that's not really my point. My point is rather that there is a sharp difference between Marxism and the soft left. One of these points of difference is that Marxists are sceptical about the possibilities for non-market forms of cooperation within capitalism. In this sense, Tim's more of a Marxist than he'd like to admit.

October 31, 2013

Against forecasts

I said yesterday that forecasting isn't part of proper economics at all. I should expand.

There is pretty much no reputable profession which rests its reputation upon forecasts. You don't expect a doctor to tell you what your next ailment will, or a mechanic to tell you the next fault your car will have. Why then, expect economists to have powers of foresight not vouchsafed to other professionals?

The question is especially acute because there are several strands of economic thinking - I'm thinking of complexity theory as much as the efficient market hypothesis - which tell us that both financial markets and economies are unforecastable.

You might object here that if economics doesn't make forecasts, it can't test its hypotheses against the evidence. This is wrong. We must distinguish between forecasting and predicting. A prediction is a conditional statement, a hypothesis, whereas a forecast is an unconditional one. "If you cut prices, then ceteris paribus, demand will rise" is a prediction. "Demand will rise" is a forecast. And predictions can be tested against actually-existing past facts - for example the hypothesis, "value stocks are riskier than others and so should offer higher long-run average returns" can (only) be judged against existing evidence.

From this perspective, the fact that so many tried and failed to predict the crash doesn't discredit economics, but actually vindicates at least three of its predictions:

- Complex emergent processes are almost impossible to forecast.

- It's impossible for most people to forecast asset prices correctly, because if they see a crash coming they'll sell up in advance and so prices would never rise so much as to crash later.

- People respond to incentives. If you give people incentives to do daft things - and economic forecasters are well-paid - then daft things is what they'll do.

It's worth noting here that some of those who are credited with forecasting the crash seem not to have actually done so; Steve Keen's precise forecasts for 2008 are hard to pin down, whilst Nouriel Roubini seems to have got a lot wrong as well as right.

Long before the crash - in 1990 - Deirdre McCloskey wrote: "The best economic scientists, of whatever school, have never believed in profitable casting of the fores." ( If You're So Smart, p109) Her comment stands.

As she points out, the belief that economists should forecast rests upon wishful thinking - of the same sort that's given us raindances, witchdoctors and ju-ju men. There's a hope that some arcane knowledge will bring us a fortune. But it can't. Worse still, there's a political urge here as well. The desire for economic forecasts is also a desire for a form of knowledge that will give us control over human events. As Alasdair MacIntyre noted in After Virtue, the claim that we can foresee and control the future is a claim to power. There's something deeply contradictory about the urge that economists both forecast the future and become more humble. You can't have both.

And herein lies a paradox. Usually, I call myself a Marxist and am in a minority. In this context, though, I'm in a minority by being anti-Marxist. Marx famously said "the philosophers economists have only interpreted the world, in various ways: the point, however, is to change it." For me, this is wrong; the point is merely to interpret the world - something we can do without forecasting it. In this sense, those who want economic forecasts are being more Marxian than me.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers