Chris Dillow's Blog, page 140

October 8, 2013

Redistribution

We tend to think that the left supports redistribution of wealth and income whilst the "right" - classical liberals if not David Cameron - opposes it. This is not true. Many rightists favour redistribution, and not merely to bankers and bosses, simply because pretty much any policy intervention is redistributive.

I'm prompted to say this by the launch of the much-derided Help to Buy scheme. This redistributes wealth from future home-owners - who'll buy at a higher price - to present-day ones,who'll see their house prices rise.

Similarly, the proposed tax break for married couples is redistributive. For a given level of tax, it means higher taxes on singletons. We could justifiably call the married tax allowance a tax on widows.

To take a different example, HS2 - if it goes ahead - will also redistribute wealth. It means higher wealth for those who own houses in those areas that benefit from better transport links, and lower wealth for home-owners who suffer noise and less pleasant country views.

Or take planning regulations. A relaxation of planning laws to permit easier housebuilding would redistribute away from nimbys towards housebuilding companies and would-be home-owners who could more easily afford to buy.

I don't say all this to support or oppose such policies - merely to note that they are redistributive.

Now, libertarians might object that such redistributions are the effect of meddlesome government. In their ideal polity, we'd simply have secure property rights and no redistribution. I'm not sure. In a minimal state, we'd still have technical change. And this itself creates de facto rights. For example, in the 19th century mid-west, the invention of barbed wire (pdf) allowed land-owners to enclose large areas, thus strengthening their property rights. In the 21st century, file-sharing gives young people the idea that they have a right to free music. Faced with such technical change, even a libertarian state would have to choose how to allocate new rights - for example, the right to shared files versus the right to protect one's intellectual property. However it chooses, there's redistribution.

I say this to endorse Frances' claim; governments don't "defend" property rights but create them.

But there's another point. It's that the political question cannot be: redistribution or not? This is because government is inherently redistributive - though I'll concede that this is more true of actually-existing governments than libertarian fantasies. Instead, the questions are: between whom should governments redistribute, and how? The principle that governments should redistribute has long been conceded.

October 7, 2013

Ignore the newspapers

Another day brings another furore about the press, the latest being about The Sun's stigmatizing the mentally ill. This poses the question: why should we fret about newspapers' misconduct?

I'll fess up here. I read the Mail most days. But I also read Holy Moly and Popbitch, and for similar reasons. I don't regard any of them as politically serious.

In fact, there's decent evidence that the political importance of the dead trees was over-rated, even before their circulation began to fall. Here's one US study (pdf) by Jesse Shapiro and colleagues:

We find no evidence that partisan newspapers affect party vote shares, with confidence intervals that rule out even moderate-sized effects. We find no clear evidence that newspapers systematically help or hurt incumbents.

This is consistent with John Curtice's assessment (pdf) of the 1997 election:

Relative to the often highly evocative and strident manner in which the British press often conducts itself, its partisan impact is a small one.

Since then, it's highly likely - given their falling sales - that newspapers' influence has declined further. In the last general election, there was no relationship between the papers' political positions and aggregate votes.

Sure, there is some countervailing evidence. Fox News does seem to have influenced American voters; a neat experiment suggests papers can affect voting; and there's evidence that local papers can encourage turnout and hence improve the vigour of local democracy.

On balance, though, we probably exaggerate the influence of the press. And insofar as this does exist, it's likely that its many infractions against decency are eroding it still further.

Insofar as voters have ideas that we leftists don't like - and in some respects they don't - it is because of cognitive biases which arise without the media's help.

Of course, journalists think that newspapers matter enormously, but then sausage-makers think that sausages matter a lot. We should take neither at their word.

I fear that lefties who fret about the Mail's antics are actually playing into its hands. Like a has-been popstar craving attention, the papers are resorting to ever-more desperate efforts to attract eyeballs. Linkbait is now a business model, and your outrage is their profits.

Let's be clear. The newspaper business is a relatively minor one - the average household spends less each week on papers than it does on fish - which doesn't deserve the attention we give it.

October 6, 2013

Complexity & alienation

In the day job, I point out that the "Mr Market" metaphor can be be misleading. If markets are complex emergent processes, as Alan Kirman shows, prices and quantities cannot be seen as the result simply of an individual's behaviour, writ large and markets are unpredictable.

Such a conception is consistent with Marxian concepts of alienation and reification. In capitalism, said Marx, "the productive forces appear as a world for themselves, quite independent of and divorced from the individuals." Or as Lukacs put it:

A relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a ‘phantom objectivity’, an autonomy that seems so strictly rational and all-embracing as to conceal every trace of its fundamental nature: the relation between people.

Insofaras there is a justification within Marx's writings for a centrally planned economy - and, right-wingers please note, Marx wrote very little about central planning - it probably lies here. Central planning is, allegedly, a means of bringing an alien process under conscious human control. In this sense, modern work on complexity helps to buttress classical Marxism.

This poses the question: should we care about alienation in this sense? I don't think we should.

For one thing, as John Roemer says (pdf), for many people, alienated work can be a liberating force. (There's an analogy with urbanism here: many people welcome the freedom that anonymous city living gives them).

And for another, it's not obvious that central planning actually can bring market forces under human control, at least not without huge cost in terms of innovation.

Instead, I suspect that the sense in which alienation mattered most to Marx - and should matter to us - is a slightly different one. It's that, in producing capital and profits, workers saw the products of their labour become means of their domination:

The object which labor produces – labor’s product – confronts it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer. The product of labor is labor which has been embodied in an object, which has become material: it is the objectification of labor...Under these economic conditions this realization of labor appears as loss of realization for the workers; objectification as loss of the object and bondage to it.

The problem here, though, is not so much alienation as domination, in the sense of oppressive working conditions, and inequality. These problems, we now know, are not necessarily solved by central planning, but are perhaps soluble by more equitable market processes.

I say all this for two reasons. First, to ask the left: what exactly is wrong with capitalism, and do those problems really need central planning to fix them? Secondly, to point out to the right both that Marx's conception of the economy is consistent with new thinking about complexity, and that one of his concerns was to expand freedom, in the sense of better enabling people to take charge of their destiny. Yes, central planning failed to achieve this, but I don't think this discredits the Marxian project.

October 5, 2013

What I learned at Oxford

It's 30 years, almost to the day, that I darkened Corpus's doors to study PPE - “a soft option for the weaker man”. Which raises the question: what did I learn so long ago that's still useful?

I didn't learn much about how to interpret economic data; econometrics came in my masters degree, and I learnt the minutiae of official numbers on the job: I gather that this is still the case, which is a shame because you can go a long way simply by knowing what the heck the ONS are playing at.

Nor did I learn anything about Austrian economics. I don't remember Hayek's name even being mentioned (though I'd read The Constitution of Liberty at school).

Here then, is what I did learn:

1. Economics is the study of mechanisms, not models. The question is: through what mechanism does X affect Y? This'll change with time and place. The task, therefore, is not (merely) to solve models, but to ask: which one is most relevant to our current situation?

2. Economic theory has a history, which can be usefully studied. There are some problems which modern economics hasn't solved but ignored.

3. Economics cannot be studied in isolation. Any serious thought about economics will soon run into political questions such as the nature of power, or philosophical and psychological ones such as the nature of rationality.

4. Don't bore your reader. "Stir me up with a good first sentence", Brian Harrison told his students. One virtue of the tutorial system is that your tutor will let you know if his attention is flagging. This means you don't have to write all you know; brevity is a virtue (I'm looking at you Frances and Bill).

5. Read the original. If you want to know what, say, David Ricardo thought, read David Ricardo, not the secondary literature - even if it'll hurt like hell. This means not relying on media accounts of speeches or data.

6. Intelligence isn't everything. Amongst my rough contemporaries, the most conventionally successful have not been the smartest (in the narrow sense of the word), but the nicest - though I'll grant this mightn't be a representative sample. And if you want a first, the self-discipline required to knuckle down and revise matters more than raw IQ.

All this said, the biggest thing Oxford gave me was a love of Leonard Cohen and Hank Williams. At this distance, the biggest impact of university is perhaps psychological, not intellectual. Readers should be grateful I stop here.

October 4, 2013

Mistaking power for virtue

Simon Wren-Lewis wonders why some economic journalists have been too generous to George Osborne's claim that austerity has worked. The answer lies with Adam Smith. We have, he says, "a disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful":

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments,I.III.29)

What the FT and Ms Flanders (to take Simon's examples) are doing in giving Mr Osborne too much credit is exactly what Gordon Brown did when he praised the "great personal warmth and kindness" of Paul Dacre. They are mistaking power for virtue.

This error mightn't be due merely to the hope of favour. As Smith said, "Our obsequiousness to our superiors more frequently arises from our admiration for the advantages of their situation, than from any private expectations of benefit from their good-will."

To put this into modern, Lakoffian, terms, what's going on here is a form of framing (pdf). The "corridors of power" frame people so well that venality and mediocrity appear as virtue and wisdom.

One way of correcting this framing is to ask ourselves of a political speech or newspaper article: what would we think of this if it were a blog? I suspect we'd overlook Osborne's thoughts as juvenile cliches. And we'd pass over that notorious Geoffrey Levy piece as mere linkbait, pausing perhaps only to wonder about the state of mental health care.

This framing-induced deference has two pernicious effects. One is that it is yet another way in which inequality feeds on itself. The other is that it helps to narrow the Overton window. In giving excessive respect to the ideas of the powerful, we help to entrench such "thoughts". And the counterpart of this is that ideas - from right and left - which aren't in the mainstream are dismissed as "unworkable" - if, indeed, they are even considered.

Luckily, though, the Overton window does shift: for example, within my lifetime, public ownership of utilities has gone from being received wisdom to unthinkable and might now be shifting back again.

Exactly how the Overton window does shift is unclear. What is clear, though, is that moving requires us to ditch some centuries-old cognitive biases.

October 3, 2013

Marxism, freedom & the Cold War

Ben Brogan's claim that Ralph Miliband was on the wrong side of "the struggle between freedom and communism" has been rebutted by Norm. There's more to add.

First, the attempt by the right - we can add Douglas Murray - to identify Marxists with Soviet apologists is very silly. There's a big strand within Marxism of libertarianism and even anarchism, which loathed the Soviet Union. For example, with the space of a few pages, Trotsky describes Stalinism as "vileness", "degeneration", "moral decay", "barbarism" and "lagging behind a cultured capitalism". In the Marxian circles I moved in in the early 80s, the debate wasn't about the merits of the Soviet Union, but rather about how best to describe its many inadequacies.

Secondly, let's ask: what sort of freedom did the pro-capitalist opponents of the Soviet Union in the mid-20th century believe in?

It certainly wasn't freedom for homosexuals, who suffered brutal repression. Nor was it freedom for young men. The slavery that was National Service did not end until 1963 - and some died during this time. Nor was there freedom for women; tough divorce laws and the legality of marital rape violated the basic principle of self-ownership. Nor was there free speech; not only did we have repressive libel laws, but also theatre censorship until 1968. Nor even was there some of the economic freedoms which today we take for granted; even the Tory governments of 1951-64 had exchange controls, laws against Sunday trading, more central planning than we have now, and public ownership of many of the commanding heights. Remember, Hayek dedicated the Road to Serfdom to "socialists of all parties", who ignored him for 30 years.

And this is not to mention Pinochet or McCarthyism...

Now, I'm not claiming here any moral equivalence between Stalinism and Conservatism. Instead, I'm making two points.

First, it is just plain stupid to pretend that the Cold War was a fight between Marxism and freedom. Many Marxists supported freedom and opposed the USSR, and many conservative Cold Warriors were enemies of freedom.

Secondly, it's not just Communists who had some evil ideas in the mid-20th century.

So, here's my offer to Ben Brogan and Douglas Murray. If you stop pretending that all Marxists are opposed to freedom, I'll not accuse Tories of murdering Alan Turing.

October 2, 2013

The intelligence curse

One of the more curious politican interventions of recent days has been claim that George Osborne thinks Iain Duncan Smith is "thick." I say this is curious not because of the tedious matter of whether Osborne really believes this, but because it's not at all clear that intelligence is a great virtue in politics.

Casual empiricism makes me suspect so. Harold Wilson was brilliant at Oxford, but was a much less successful PM than Thatcher, Blair or Churchill who weren't noted intellectuals. And intelligent men such as Oliver Letwin, Tony Wright and David Willetts (to name but three) haven't had stellar political careers.

One reason for this lies in the nature of politics. Many political problems are either insoluble, or have quite simple solutions which are unsellable (basic income, voluntary jobs guarantee, drug legalization). For the former category intelligence is useless, for the latter unnecessary.

But there's another reason. It's that intelligence (in the narrow sense of IQ or book-learning) can crowd out other virtues. For example:

- If you're so brilliant you can pick things up quickly, you'll not develop the determination and stickability you need to cosy up to dullards, sit through interminable meetings or plough through red boxes.

- Intellectuals want to say something interesting. And this leads them into "gaffes". Keith Joseph's flirtation with eugenics is the most notorious British example of this, but Larry Summers has made a career of it.

- Intellectuals are, very often, out of touch; they might well therefore lack the political antennae which tells them what'll sell and what won't.

- Intelligence can lead to one of two possible drawbacks. Sometimes, it can breed indecisiveness, which might have been Wilson's problem; being able to see both sides of a problem can rule out clear and decisive leadership. At other times, it might lead to overconfidence and hubris. The poll tax, remember, was the idea of intelligent people.

But here's the thing. All this doesn't just apply to politics. I suspect it's true of many other careers.Miriam Gensowski has estimated (pdf) that, among high-IQ people, the link between IQ and earnings is not significant; it's conscientiousness and social skills that matter more. Beyond a certain level, then, intelligence doesn't matter. And even across a wider ability spectrum (except perhaps at the very low end) it matters less (pdf) than many believe (pdf).

Personally speaking, all this is consistent with introspection. I suspect that if I had a higher IQ (and I have no idea what my IQ is), my life wouldn't have been much different - and if it had been, I might well have been poorer rather than richer. If I'd had better social skills, ambition or a capacity to tolerate boredom, however, I might well have been more "successful". I know it's dangerous to generalize from personal experience (especially mine!) but mightn't this be more widely the case?

Another thing: for Christ's sake, don't claim that IDS's advocacy of workfare and benefit caps shows he's thick. The idea that people would agree with us if only they were more intelligent owes more to self-love than to serious thought.

October 1, 2013

Are jobs a cost?

Tim Worstall says:

Jobs are a cost of producing renewables, not a benefit of them, just as with anything else. We want to produce whatever it is we want to produce with the least use of human labour, not the most.

I'm not so sure.

Tim would be right if we had full employment. In such a world, the opportunity cost of having a worker in a low-productivity job is having him in a higher-productivity job. In this sense, low-productivity jobs are a cost. Tim's right, therefore, that - in the long-run, and assuming displaced workers find employment - the sort of technical progress which "destroys jobs" is actually a good thing - as it frees people up to do more useful things*.

However, the more astute of you might have noticed that we don't have full employment. And this changes things. This is because unemployment is costly. The social cost here is not so much the welfare benefits paid to the jobless: these are, in effect, a transfer from taxpayers to Lidl, Matalan and landlords. It is rather that the unemployed are much, much less happy than the employed. This is not simply because they have lower income. "Becoming unemployed is much worse than is implied by the drop in income alone" say (pdf) Di Tella and colleagues. One reason for this is that the jobless suffer from feeling that they are violating social norms about the value of work.

From this perspective, jobs are a benefit; they help - perhaps only partially - to restore people's self-respect and well-being. This might even be true of work that's of questionable conventional "value"**. In Bridge on the River Kwai, Lt. Colonel Nicholson gets his men to build a great bridge - even though it would help the Japanese war effort - because it's a way to improve their pride and morale. I suspect that story generalizes; even digging holes and filling them in again might help increase happiness by improving the unemployed's social contacts and friendships. (It is, of course, a long leap from saying this to saying that work programmes must be compulsory.)

That said, this is is not an argument for creating low-value jobs. Within a voluntary job guarantee scheme, there's an opportunity cost to paying people to dig holes and fill them in again; it's that they could be doing something more useful***.

In this sense, Tim's right that we should pay attention to the quality of jobs that are being created. But to say that "jobs are a cost" is - at our current juncture - far too simple.

* One might quibble here about the quality of jobs. But I suspect the idea that call-centre work is worse than mining or old-style farming owes more to romantic nostalgia than to facts.

** I hate the word "value".

*** The fiscal cost of a job guarantee scheme is another question; if multipliers are below one, it is a cost, but if it's above one, it's not. But this is not the point Tim's making, which is probably just as well.

September 30, 2013

Help to work?

I fear there's an element of dog-whistle politics in George Osborne's "help to work" plan - the whistle being that he's appealing to those who wish to blame the unemployed for their plight under the guise of helping them. I say so for the following reasons:

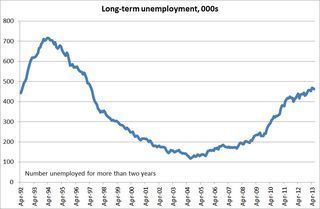

1. This is not really about being "fair to those who pay for welfare" simply because the net exchequer cost of long-term unemployment is low. There are now 462,000 who have been out of work for over two years. With JSA at £71.70 per week, this costs £1.7bn per year - a little over 0.1% of GDP, which is well below the forecast error in government borrowing*. If Mr Osborne is serious about helping the jobless find work and reskilling them, this'll cost money. An "intensive regime of support" for addicts and illiterates won't come cheap. As I've said before, scrounging is not a major macroeconomic issue.

2. Unemployment is a massive source of unhappiness. ONS data show that whereas only 3.7% of those in work report very low life satisfaction (0-4 on a 0-10 scale), 14.1% of the unemployed do. Worse still, the unemployed do not adapt to their situation. This suggests that, if Mr Osborne's offer of help is sincere, there needn't be any element of compulsion in it because - for the most part - the long-term unemployed do want to work.

3.There's strong evidence that many (not all) workfare programmes fail (pdf) to get people into lasting employment. This warns us that, in the wrong hands, such schemes can be more of a way of harassing and stigmatizing the unemployed than actually helping them.

4. There's a big cyclical element in long-term unemployment. It rises in recessions and falls in booms. At it's low-point, there were fewer than 150,000 who'd been out of work for two years or more. The present rate is three times this. This suggests that long-term unemployment is more about macroeconomic conditions than workshyness and folk wanting something for nothing.

Now, I don't want to be too hard on Osborne here; his speech wasn't as harsh on the unemployed as I'd feared it might be from this morning's reports. And given the huge welfare cost of joblessness, any genuine help for them is to be welcomed. I just wish politicians (of all parties) wouldn't try to mix this with the base motive of encouraging people to blame the victim.

* Yes, the unemployed are entitled to other benefits, but they're entitled to some of these if they get low-paid work.

September 27, 2013

Misallocating blame

After the battle of Arginusae in 406BC, six Athenian generals were executed for failing to rescue some shipwrecked sailors, even though they could not have done so because a violent storm (pdf) prevented them.

Many of you might think this unjust. The Kantian control principle says we shouldn't blame people for bad luck. We moderns, then, surely wouldn't make the same error as the Athenians.

Oh yes, we would, according to some recent experiments by Joshua Miller and colleagues. They split subjects into a principal and agent. The agent chose between a safe option and a lottery, and the principal then split a sum of money between himself and the agent after seeing the outcome of the lottery. They found that principals' payments depended upon the outcome of the lottery, even though this was obviously out of the agents' control. For example, agents who chose the safe option were paid less if the lottery won than if it didn't:

Principals in our experiment clearly exhibit unjustified blame: they adjust the payment to the agent according to the difference between the realized outcome and the outcome of the alternative the agent had not chosen, even though it is clear that he was not responsible for the outcome.

This isn't a lone finding. It's consistent with research by Jordi Brandts and by Nattavudh Powdthavee and Yohanes Riyanto which has also found that people just can't distinguish between luck and skill even in the elementary conditions.

I fear that this might have important social consequences. If we muddle up luck and agency, we'll be apt to blame the poor too much for their misfortune, with the result that redistribution towards them will be less than it otherwise would be. What's more, we'll also be too indulgent towards the rich. We'll think that success is due to ability when it might be due to luck, and so tolerate mega-buck salaries. We'll also misallocate resources by creating a demand for forecasters, share tippers and active fund managers, most of whom owe what little success they get to luck rather than skill.

To the extent that this is the case, our tolerance of inequality is founded upon a simple error (and not just this one - but that's another tale). Perhaps we haven't made as much progress since ancient times as the self-regard of our age would make us believe.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers