Chris Dillow's Blog, page 143

August 30, 2013

Cameron's tragic failure

David Cameron is a terrible advert for Oxford PPE. He's long been ignorant of economics - as his prating about the "nation's credit card" and the "global race" attest - but his defeat last night suggests he knows little about politics and history too.

It's a cliche that this was a failure of leadership. I suspect, though, that it was a failure to even see what leadership is. Leadership is the art of getting people to follow you when they don't have to; if they do so because they must, you're not a leader but a boss.

But leadership in this sense is not just about speechmaking and doing the right thing. It's about getting dirty, and using the darker arts of politics.

One such art is timing. If your position is strong, you should act. If it's not, you should wait. Had Cameron waited until the UN inspectors have reported, his case would have been strengthened by reports of the incendiary bomb attack on a school.

But there's another failure. Leadership also means identifying potential oppenents and cajoling them - maybe nicely, maybe not - into supporting you. And at this, Cameron has long been poor. Fraser Nelson says he's "aloof." And only a few months into his permiership one Tory sympathizer wrote:

There is little affection for Cameron on the Tory benches. His regime is chilly, even aloof. MPs who cross him know that they are unlikely to be forgiven. Slowly, the numbers of the disaffected and dispossessed are growing.

Contrast this with two great American leaders - Abe Lincoln and Lyndon Johnson. Their success rested on not so much on them taking the moral high ground - the best that can be said for LBJ's "moral compass" is that it wasn't quite as defective as Nixon's - but on their ability to twist arms, and appeal to low motives.

Their precedents are, I think, relevant. Both men faced parties which were loose and fissiparous, which is the condition of today's Tories. Not only are they intellectually divided - for example on both social and economic liberalism - but they are also socially so; the Cabinet might be full of public school millionaires, but the backbenches aren't. His long failure to close this gap means that Cameron lacked both the ability to convert potential rebels and the trust which was necessary to induce people to follow him on what would have been a speculative venture.

In this sense, there's a tragic aspect to Cameron. He has thought of politics as (by his own lights) a noble venture - as when he pushed through gay marriage and in his desire to stop crimes against humanity. But politics isn't just that. Sometimes, to win a moral crusade you need immoral means. Leadership isn't about being like Martin Luther King, but being like Lyndon Johnson.

August 29, 2013

Tattoos, options & cognitive biases

A recent post of mine prompts the thought: doesn't the rise of tattooing raise some important economic issues?

What I mean is that we can think of getting a tattoo as an irreversible investment (pdf); removing them is expensive and painful, so in this respect they differ from piercings. And the thing we know about irreversible investments is that the threshold for undertaking them is typically quite high.This is because such investments (sometimes) have an option value - we have the option of exercising them later rather than now - and it often pays to hold onto such options.

This raises the question: why, then, do people want to exercise the option of getting a tattoo, rather than hold onto it?

Two cognitive biases are relevant here. One is the projection bias (pdf) - our tendency to under-estimate the extent to which our tastes will change in future. Just as we will undervalue equity options if we under-estimate future volatility, so we'll undervalue the the option of waiting to get a tattoo if we under-estimate the volatility of our tastes, and thus be more likely to get one now. In this context, a tattoo of one's football team is more rational than one of one's partner - your team is for life but your lover isn't.

The second bias is the present bias - the tendency to underweight the future. The more we discount our future selves - and the possible regret they will feel - the more we're likely to get a tattoo. This has some testable implications:

- People prone to such bias are more likely to have tattoos. Ceteris paribus, we'd expect people with lots of credit card debt (pdf) to have tattoos, as both are products of present bias.

- We'd expect criminals to be especially likely to be tattooed, to the extent that committing crime betokens a present bias, a failure to see that one's future self could end up inside.

- We're more likely to get tattoos if we feel sad, because sadness increases the extent of present bias. Getting inked after splitting up from one's partner should thus be common.

How does all this fit with the fact that the prevalence of tattoos has boomed in recent years? It could be that they are a product of a more egocentric culture - an artefact of neoliberalism? If folk become more egocentric, then we'd expect to see more tattoos to the extent that tattooing priveleges the present self over the future one. It could be, then, that the spread of tattooing is like household debt, "culture wars" over religion or the popularity of radio phone-ins. All are products of the age of ego.

Another thing: I suspect peer effects also matter here; folk get tattooed if their peers are. This might be why footballers - a group susceptible to peer pressure - are tattooed more than, say, individual sportsmen are.

August 28, 2013

Syria, trust & knowledge

There's one view of how the UK should react to the Syrian crisis that hasn't - with the possible exception of Robert Halfon (11.23" in) - been expressed. It's something like this:

This is not a matter for parliament or the public to debate. With a few exceptions - some of them of no account - everyone agrees that if Assad has used chemical weapons there is a moral case for restraining and punishing him: don't forget that intervention sometimes works. The question is one of practicality; is it possible to intervene for the better? Here, any fool can think of a dozen hypotheses why intervention might fail or backfire. Whether these hypotheses are correct depends upon conditions on the ground in Syria, of which most people - including MPs - have insufficient knowledge. Rather than have parliament debate the matter - which'll just give us pompous windbaggery and weaselling about the law - the decision should be taken by the PM, under guidance from the intelligence agencies who know the details of what's happening. This is a matter that should be left to the experts.

There's a big, obvious reason why almost nobody's saying this. It's that, since at least the "dodgy dossier", nobody trusts the security services at all.

Which raises an important point. Trust is not merely some airy-fairy moral concept or PR guff. It's an important real asset for an organization. The fact that the intelligence agencies don't have it severely impairs their ability to fulfill one of their proper functions, of informing the decision to go to war or not.That's a material weakness.

But the distrust should, I suspect, go further than this. The point Hayek so rightly made about economic knowledge - that it is fragmentary, partial and unreliable - applies even more to military intelligence. There's a reason why "for want of a nail" is an ancient rhyme; in war, tiny details can have huge effects. The concepts of complexity and emergence apply perhaps even more to civil wars than to other social phenomena.

There are some things which it is perhaps impossible to know. The fact that everyone seems to have an opinion on Syria tells us more about the ease which opinions are formed than it does about what is actually happening in Syria or about the nature of knowledge.

August 27, 2013

Limits to agency

Do the poor lack free will? I ask because of a Twitter argument I've had with Peter Risdon. I said that in criticizing the poor for their junk food diet, Jamie Oliver was blaming the victim. Peter replied: "You think that being poor removes from individuals the ability to decide how to act, albeit within limits affected by poverty?"

I'll not go as far as "removes." But I would stress the many channels in which the poor's agency to act "well" is constrained. These include:

- Poverty limits options. If you're poor, you're more likely to live in a food desert where healthy eating is less feasible. Sure, you could get nutritious food cheaply or even for free if you look in the right places. But to believe this is true for all the poor is to commit the fallacy of composition. And of course, this is only one of many ways in which poverty limits freedom; not least of the others is that poverty is associated with poor education.

- Social roles, priming and stereotype threat. The famous Stanford prison experiment showed how people quickly come to take on social roles, even if these are randomly assigned: guards became belligerent and prisoners docile. "Most of us can undergo significant character transformations when we are caught up in the crucible of social forces." writes Philip Zimbardo.People live up or down to stereotypes, especially if they are reminded of them. So if the poor are told that they are mindless, low-achieving criminals, they'll act the part.

- Learned helplessness and adaptive preferences. If people are told (for generations) by teachers, rulers and bosses to "do as your told" many will eventually become passive, and unaware of what agency they have. And if they have few attractive job opportunities, some will resign themselves to that, and become "lazy."

- Bad incentives. What's the point of getting a job if you lose benefits and face high costs of travelling and childcare? What's the point of doing well at school if you'll face social isolation (not just a problem for blacks)? Why save if you'll only be robbed?

- Role models. If you see people like yourself doing something, you'll think "I can do that". This is one reason why we often follow our parents' career paths; Jamie Oliver's parents ran a pub, and it's a small step from there to a career in cooking. If, though, you lack such models, you'll be less aware of your options.

- Peer effects. It's increasingly well known that our peers shape our choices. If our mates go to university, we're likely to. If they become criminals, so are we.

Now, in saying all this I'm not wholly denying that the poor have free will. It's just that it is a damned sight harder for them to choose well than it is for people in more favourable circumstances.

Nor is it only the poor who are constrained. There's not much agency involved when an Etonian goes to Oxford and thence to politics or the City: As Owen Jones rightly wrote, David Cameron is also "a prisoner of his background." Marx was aware that capitalists' choices are constrained by the forces of competition. And capitalists are themselves quick to deny their own agency when they claim that job cuts or austerity are "necessary."

Agency, in any fullish sense of the word, requires particular conditions which are only rarely met. What robs the poor of dignity - to use Peter's phrase - is not my pointing out the degree to which they lack free will, but rather the existence of those social conditions that limit it.

August 26, 2013

HS2: how to decide

Last night John van Reenen tweeted that the controversy about HS2 shows that we need a better way of making decisions about big infrastructure projects. He's right. Economists have known the answer here for years. We should use a demand-revealing referendum, as proposed by Ed Clarke.

The idea here is simple. We hold a referendum in which everyone in the country is asked to state the net benefits to them of HS2; as the scheme is likely to cost each voter at least £700, these benefits will be negative for some/many voters. Then we add up all the answers, and if we get a positive number we go ahead, and if it's a negative one we do not. Finally, we check the net total benefit against individual voters' stated benefits. If any voters stated so large a sum that their vote was pivotal, they must pay a tax equal to the difference.

This method has some huge virtues.

One is that it's decentralized. Instead of the HS2 decision being taken by a few special interest groups after what John Kay calls a "dismal" cost-benefit exercise, the decision is taken by everyone. Sure, voters' stated benefits will be wholly subjective. But this is a feature not a bug; as James Buchanan argued, costs (and benefits) are subjective.

Secondly, it's incentive-compatible. If you state too small a sum, you risk not getting your preferred option. If you state too big a sum, you risk being taxed. A demand-revealing refernedum thus forces voters to be honest.

Thirdly, if the use of such referenda were to be widely adopted, it would improve out political culture. There'd be no place for blowhards and windbags who overstate their case. Instead, they would have to proportion their estimate of net benefit to the evidence. We'd get much more reasonable, grown-up politics.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. Demand-revealing referenda are in theory wholly consistent with neoliberal ideology, because they reject the top-down central planning of Whitehall-run cost-benefit analysis in favour of a market process. And yet such referenda fall well outside the Overton window, and are proposed only by cranky extremists like me.

There is, though, a simple solution to this paradox. Adopting demand-revealing referenda requires that politicians and vested interests give up their power. And this won't happen. Power trumps ideas.

August 25, 2013

Cheryl Cole & the decline of liberalism

In achieving the unlikely feat of making her arse look unattractive, Cheryl Cole has drawn our attention to one of the most significant cultural changes of recent years - namely, the change in attitudes to self and identity as betokened by the boom in the number of people with tattoos.

In my formative years, pretty much the only people who had tattoos were sailors, convicts and bikers. This was because, to us, nothing mattered so much that we wanted a permanent mark of it on our bodies. The breakdown of traditional class, gender and religious sterotypes in the 60s, 70s and 80s led to a fragmentation and weakening of senses of identity. And insofar as identities did still exist, they were things to be escaped from, as tools of class, gender or racial oppression; it's no accident that slaves and concentration camp victims were branded and tattooed.

This was reflected in pop culture. The most iconic pop stars of the 70s and 80s were David Bowie and Madonna, who adopted and discarded identities and personas. And the most significant pop lyric was "This means nothing to me."

We were - whether we knew it or not - postmodernists, Rortyean ironists who kept a distance between our "selves" and our beliefs and our identities.

What we're seeing with the rise of tattoos is a backlash against this, a desire to close this gap - to identify the self/body with what one believes or loves. Whereas my generation had the artifice and alienation of Bowie and the new romantics, today's tattooed generation has "urban" music and pseudo-folk singer-songwriters with prentensions of being "real" and "authentic." "Humankind cannot bear very much reality" wrote T.S.Eliot. But nor can it bear very much scepticism and alienation. The atomic individual of liberal and conventional economic imagination - Amartya Sen's "rational fool" - is not something people aspire to be.

Does this matter? Perhaps, for two reasons.

One is that it is potentially illberal. The more people identify with their beliefs, the more they are likely to regard challenges to them as not just a clash of ideas, but as affronts to their selves. The rise of tattoos and the increase in the numbers of people "taking offence" are in this sense two aspects of the same phenomenon.

Secondly, as Akerlof and Kranton have shown, identities influence our economic behaviour. Our perceptions of who we are, and of whom we wish to identify with, shape not only our consumption decisions but also our career choices. There is, therefore a danger that identities might constrain our options and limit social mobility, by trapping people into gender, class and ethnic roles.

August 24, 2013

Labour's cost of living problem

Hopi Sen says he's a "cost of living sceptic". He'll not thank me for saying so, but I agree.

First,let's be clear way real wages have fallen. Duncan's right to say that inflation is not to blame, simply because we've seen many periods of inflation around current levels without falling real wages. Blaming inflation for falling real wages is like blaming plane crashes upon gravity.

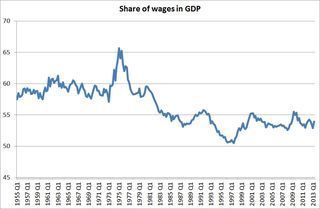

Nor is it because workers' incomes are being squeezed by more powerful capitalists. In recent years, the share of wages has been more or less flat; this week's figures show that the wage share of GDP is actually slightly higher than it was before the recession.

Instead, real wages have fallen simply because there's a massive excess supply of labour. If we add part-timers who'd like a full-time job and the inactive who'd like to work to the measured unemployed, there are 6.2 million waiting to work more - equivalent to 15.4% of the working age population. And there's an unknown number who are under-employed on the job.

Policies to increase real wages must, therefore, include measures to reduce this excess supply. And herein Labour faces two constraints. One is its commitment to some form of fiscal restraint. The other is that it faces demands (sadly from working class voters too) for "welfare reform", the effect of which would be to strengthen people's incentives to look for work, thus raising the labour supply.

Granted, there is an alternative here* - to raise workers' share of GDP, in ways suggested (pdf) by Howard Reed and Stewart Lansley. But here too, there are big constraints. Policies to increase minimum wages and strenthen collective bargaining would be resisted by capital, and it's possible that even if such measures were enacted, capital would respond by cutting investment and demand for labour; we cannot be confident that wage-led growth is feasible.

All of which brings me to endorse Hopi's point - that Labour's proposals to raise real wages are "small-scale.". He's right to say: "we’re setting up a general ‘crisis’ of living costs, against which our solutions then seem somewhat insignificant."

Herein, I think, lies a reason for Ed Miliband's much-criticized failure to push his economic message; he's aware of this big gulf between the size of the problem and the smallness of his answers.

However, to believe this is due to Miliband's personal, idiosyncratic weaknesses is to commit the fundamental attribution error. Labour's problem isn't a lack of "leadership" but rather that there are serious constraints upon what any social democratic government can achieve.

* You might object that there is one alternative that is very politically feasible - to have tougher immigration controls. However, there's no evidence that these would raise real wages, except slightly at the bottom end of the labour market, and even then only temporarily.

August 23, 2013

Demand curves

My post on rent control set me wondering: is there really such a thing as a downward-sloping demand curve for housing?

I ask because of simple introspection. If house prices were to fall sharply, I would not buy more. Nor would I buy less if prices rose. This is simply because I'm content with the house I've got. My "demand curve" for houses is a vertical line at zero, and I guess the same is true for millions of owner-occupiers. Granted, a fall in prices would allow some renters to buy. But their demand would simply rise from zero to one, and stop there. That's not the smooth line or continuous function of the textbooks.

Sure, there might be some property speculators who would increase demand as prices fell. But these are a small minority.

How, then, can we speak of a conventional demand curve for houses? If such a thing exists at all - which I doubt* - it is likely to exist not at the individual level, but in aggregate; a small drop in price would allow a few people to become owners rather than renters, and a larger drop would allow more to do so. In this sense, an aggregate relationship isn't simply a typical individual's behaviour writ large.

It's not just housing of which this is true. In a study of the Ancona fish market Alan Kirman and colleagues showed that, for very many individual buyers, there was no negative relationship between price and quantity demanded, and in many cases there was a positive relationship. But there was a downward-sloping demand curve in aggregate. They say:

The aggregate characteristic, the negative relation between price and quantity, is not a reflection of individual behavior.

I say this for two reasons. First, to question "representative agent" theory. What's true at the aggregate level need not true for a typical individual. Instead, outcomes are the product of complex emergent interactions.

Secondly, to counteract a common bias in our thinking about the role that networks and interlinkages play in economics. Insofar as we think about these - and we don't do so enough - we consider them as a destabilizing force; for example, when links (pdf) between banks created systemic risk, or when information cascades cause stock markets to fall. This, though, is only part of the story. As Kirman has shown, aggregation can also generate conditions for stability - such as downward-sloping demand curves - which are not necessarily present at the individual level.

* In practice, aggregate price and quantity demanded are positively correlated, simply because both are driven by the same things; incomes, credit availability, interest rates etc. To get a downward-sloping curve thus requires some careful controls. And even then we might have the problem of extrapolative expectations: a fall in prices might lead to lower demand, to the extent that potential buyers expect prices to fall further.

August 22, 2013

Agents of freedom

August 21, 2013

A case for rent control?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers