Chris Dillow's Blog, page 147

July 3, 2013

The investment problem

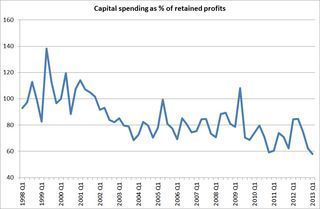

The UK is recovering. Surveys by Markit and the BCC show that output and orders are rising. There is, though, (at least) one big black cloud here, shown in my chart.It's that firms are still loath to invest. In fact, in Q1 non-financial companies capital spending fell to just 57.9% of retained profits - the lowest rate since records began*. I'm not sure things have much changed since March. The BCC's otherwise up-beat survey found that services companies' capex is still low, and Bank of England data show that firms are still increasing cash piles and repaying debt - consistent with a continued aversion to real spending.

It's hard to blame this investment dearth upon firms being forced to save by credit constraints. Today's Bank of England survey shows that the availablity of credit to firms has generally increased since 2010. And April's CBI survey (pdf) found only 12% of manufacturers saying that a lack of finance is a constraint upon investment.

So, what is the problem? There's a cyclical problem of weak demand; that CBI survey found 54% of firms saying investment was constrained by uncertainty about demand and 40% saying it was constrained by inadequate prospective profits. I'd add that this is overlain upon a longer-term lack of monetizable investment opportunities: note that the fall in the ratio in my chart came in the early 00s, and not during the crisis.

You might, however, suggest another, rosier possibility - that the relative price of capital goods has been falling, so that a given amount of nominal spending now goes further than it did: the prices of business investment goods haven't change much since the early 00s, which means they have fallen considerably relative to the GDP deflator.

This possibility, though, runs into two problems:

- Why isn't the price-elasticity of demand for capital higher? If it were greater than unity, then, we'd have seen nominal investment rising rather than falling.

- It deepens the productivity puzzle. It's sometimes said that labour productivity has stagnated because firms have substituted from capital to labour. However, since 2010 capital goods (measured by the business investment deflator) have fallen by around five per cent, pretty much the same as real wages. Now, it's perfectly possible for there to be capital-labour substitution without a change in relative prices. But to the extent that there has been, it's hard to attribute this merely to the drop in real wages.

Whatever the reason for weak investment, two things are clear. One is that we'll not get a decent recovery unless this changes. The other is that the long-term weakness in capital spending seems inconsistent with neoliberal notions that low business taxes and a quiescent labour force will increase investment.

And herein lies my worry. Low taxes and weak workers might not be sufficient to promote investment. But it is theoretically possible that they are necessary. If so, then the social democratic response to neoliberalism might be inadequate.

* The new vintage of data only goes back as far as 1998; the ONS is even better at expunging figures from history than Stalin was. However, previous vintages of data show that capital spending was a far higher share of retained profits in the 1980s and 90s - quite often exceeding 100%.

July 2, 2013

Basic income vs capitalism

Izabella Kaminska wonders whether it's time to take the idea of a basic income seriously? This raises a paradox.

On the one hand, the merits of a guaranteed income for all seem clear:

- It would be simple to administer, which should appeal to governments wanting to cut "wasteful" public spending.

- In giving an unconditional income to all, workers would be able to take on insecure jobs, training, internships or zero-hours jobs without fear of losing their benefits. In this sense, A BI underpins the flexible labour market.

- A BI could free people to do voluntary work, thus helping to promote the "Big Society."

- In replacing tax credits, A BI could well be associated with lower marginal withdrawal rates (pdf) than at present. This could increase work incentives.

The case for some kind of BI, then, seems strong. And herein lies my paradox. If the case is so strong, why has it for years not been considered by the main political parties, other than the Greens?

It's not obviously because it's unaffordable. I reckon a BI of around £130 per week - £20 more than the basic state pension and almost twice the JSA rate - could be paid for by scrapping current spending on social security and tax credits and by abolishing some of the many tax allowances (pdf), the most important being the £62.5bn cost of the personal allowance.

Instead, it's because A BI breaks with a fundamental principle of the welfare state. This, wrote Beveridge in 1942, is "to make and keep men fit for service.*" One function of the welfare state is to ensure that capital gets a big supply of labour, by making eligibity for unemployment benefit conditional upon seeking work. BI, however, breaks this principle.In its pure form, it allows folk to laze on the beach all day.

For many of us - including Philippe van Parijs who first alerted me to the merits of BI - this is not a bug but a feature. Jobs are scarce, so it's better for workers if some are subsidized not to seek them, leaving more opportunities for those who do want to work.

However, this is certainly not in the interests of capitalists, who want a large labour supply - a desire which is buttressed by the morality of reciprocal altruism and the work ethic. It is the fear that a BI would lead to mass skiving that keeps it off the political agenda.

Is such a fear justified? I don't know. Empirically, it's ambiguous, as a BI would - as I've said - in some ways improve work incentives. For capitalists, though, it is a risky prospect.

My suspicion is that a full BI is, for this reason, incompatible with capitalism. Yes, it might well be efficient in many ways. But capitalism is about maximizing profits, not utility.

* I can't find the full text of the Beveridge report online. The quote is on p170 of the version I read ages ago.

June 29, 2013

Immigration, class & ideology

One of my neighbours has been ill recently, so some of us have been maintaining her garden for her. Are we helping her or not?

It seems like a stupid question. I ask because of how Janice Turner in the Times (£) describe how her old school friend, Dave, changed from being a leftie to a supporter of the English Democrats:

The company, a high street retailer, preferred [immigrant workers] to union members like him. The warehouse had "high bays", areas where vast palettes are stored 100ft up. To avoid people below being squished, they are off-limits to all but trained staff. But awash with pre-Christmas business, the company wanted to site "picking aisles" - where staff meander, putting together an order - beneath the high bays. The unionized British workers refused but, using immigrant agency labour, the company did it anyway.

This, as Dave tells it, was the start of his political disillusionment.

But the migrant workers are doing just what we're doing for my stricken neighbour. I am migrating from my house to my neighbour's to do a job she doesn't feel up to, just as they are migrating from Poland to Doncaster to do a job Brits don't feel like doing. So, why is my migrant labour seen as a help whereas Poles' labour is considered a menace?

Two reasons.

First, the connection between migrants' labour and the benefits to others is less salient for Dave than it is between me and my neighbour. He doesn't see that the migrant labour is a complement to others' work - for example, the faster orders are put together, the more work their is for delivery drivers. And he doesn't see that, if immigrants work cheaper and faster than others, then prices are lower, which boosts customers' real incomes which allows them to spend more elswhere, thus creating jobs. Nor does he see that, ultimately, migrant labour might free him to take more productive work.

Secondly, whereas the effects of my labour fall upon a unified person - my neighbour - the effects of immigration take place in a class-divided society. For those in power, the benefits - high profits - are quick and easy. But for those at the bottom end of the labour market, they are less pleasant.

But it needn't be so. Imagine our retailer were a full-blooded worker coop. Workers would then think: "Isn't it great we don't have to that dangerous job now, so we can do nicer jobs and get a share of higher profits". And if redundancies are made, they'll be on better terms. (And of course, in a society not disfigured by class division, unemployment benefits would be higher).

In this sense, it is obvious that immigration - insofar as it does worsen the condition of some workers (which is easily overstated) - is a class issue. Rather than ask: "why are immigrants taking my job?" Dave could equally ask: "why are there class divisions which prevent the benefits of migration flowing to everyone?"

So, why is one question asked when the other isn't? The answer is that capitalist power doesn't just determine who gets what, but also what issues get raised and which don't. As E.E.Schattschneider wrote in 1960:

Some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out. (quoted in Lukes, Power: A Radical View, p20)

In this way, it is immigrants who get scapegoated rather than capitalists.

June 28, 2013

Celebrating failure

For a long time, people like me have accused politicians of importing into government the habits and ideology of corporate management. Listening to Osborne on Wednesday, however, made think that this accusation is wrong.

Take this passage:

I also said three years ago that I was confident that job creation in the private sector would more than make up for the losses [in the public sector].

That prediction created more controversy than almost anything else at the time.

Instead, every job lost in the public sector has been offset by three new jobs in the private sector...

A central argument of those who fought against our plan completely demolished by the ingenuity, enterprise and ambition of Britain’s businesses.

He's forgotten something here. Back in 2010, he thought the private sector would create jobs because the economy would expand. But the expansion has been much weaker than expected; In June 2010 the OBR forecast (pdf) that real GDP would be 9.5% higher in 2013 than in 2009. If its latest forecast is correct, it'll be only 3.8% bigger.

This poses the question. If real GDP is 5.2% less than expected, how can Osborne still rejoice about job creation?

Simple. It's because productivity has fallen.Rather than celebrate businesses' "ingenuity, enterprise and ambition", Osborne should be cheering their increased inefficiency.

The numbers here are huge. If GDP per person in employment had stayed at its 2008Q1 level, there would now be 1.3m fewer people in work than there are. If GDP per worker had risen by 2% a year - as it did in the 10 years to 2008 - there would be four million fewer in work. If half these showed up in the jobless count, we'd have 4.5 million unemployed.

Now, I don't think Osborne deserves any credit for this fall in productivity. And, in fairness to him, he's not claiming any. I've not heard any Tory say; "thanks to our policies, British business has become more inefficient."

But this is not the only way in which he's claimed credit for something he's not responsible for. He also rejoiced in the "£6 billion pounds a year less we are paying to service our debts." But the main reason why debt service costs are low is that gilt yields are (still) low (for now). And the main reason for this is that the (global) economy is so weak. Again, he doesn't deserve credit for this.

Instead, he looks like an in competent rifle-shooter who shoots wildly at a wall, and then paints targets around his bullet holes and shouts "Yay, I hit them." I suspect that if we'd had more normal productivity growth and higher unemployment, Osborne would be celebrating the increased leanness and efficiency of British business.

And this is why I say that government is insufficiently businesslike. Any competent business benchmarks itself against pre-existing targets. The man who misses some targets, hits others only by luck and who invents others after the fact would soon be dismissed as an incompetent bluffer.

In some senses - contrary to my general view! - perhaps we need more managerialism in government.

June 27, 2013

Not a fiscal problem

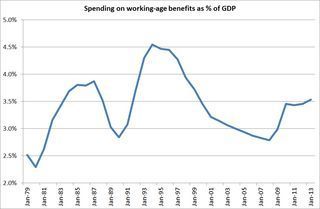

There's one point about the government's proposed benefit cap that's so obvious I'm embarrassed to point it out. It's that spending on non-pension benefits is not so much a fiscal problem as a labour market one, and an international one at that.

What I mean is that since the 1970s there's been a decline in demand for unskilled (pdf) workers across the western world. This has led to a combination of worklessness, economic inactivity and/or poverty wages across Europe and the US. This was the main reason why, even before the crisis, over five million (pdf) working-age Brits were claiming benefits. And it's this that explained why spending on benefits rose as a share of GDP so much between the 1970s and 90s.

In this context, the UK is not obviously an outlier. The OECD estimates that in 2010 (the latest year for which we have figures), only 56% of UK people who left school before 18 were in work. That compares to 85.1% for people with degrees. But these numbers are close to the OECD averages, of 55.5% and 83.1% respectively.

The UK's problem, then, isn't that we have an abnormal number of workshy unemployables. Nor is it - as my chart shows - that working age benefits are unusually high as a share of GDP right now. Instead, it's that we have been victims of a worldwide problem.

This suggests that if we want to cap working age welfare benefits, we should get more people into work.

And herein lies a hope,. It could be that the relative fall in demand for unskilled workers has stopped recently; it has been middlingly-skilled workers who have been displaced by technology recently, not grunt workers. This is consistent with benefit spending falling as a share of GDP in the 00s.

Whether this can continue is, of course, impossible to say; knowledge of the future is a contradiction in terms. My point is simply an obvious one which Keynes made 80 years ago:

Look after the unemployment, and the Budget will look after itself.

June 26, 2013

Two views of the state

The big divide in politics isn't (just) between left and right, but between statists and anti-statists. This is the lesson of the Prism affair and of the Met's snooping on the Lawrence family.

The issue here is how we think of the state.If you think the organs of the state are passive tools which promote the public interest, you might be appalled by these revelations. Anti-statists, by contrast, merely feel vindicated. To public choice libertarians, government agencies are not mere arms of the public, but agents with their own interests who want to expand their powers and budgets. From such a perspective, the police's desire to cover up its bungled inquiry into Stephen Lawrence's murder or the Hillsborough disaster, and the expansion of the NSA's and GCHQ's operations are not examples of agencies being "out of control." They just show what such agencies do; they cover up their inadequacies and seek to increase their powers.

On this point, Marxists and right-libertarians have common ground. These examples vindicate Lenin's view that the police and security forces are "special bodies of armed men placed above society and alienating themselves from it." And the very existence of the Special Demonstrations Squad corroborated Marxists' belief that the state served the interests of capital. Why else would the police devote so much effort to protestors against McDonalds and power stations when they were, at worst, only low-level criminals? It because they inconvenienced capital. And as Marx said, the state is "a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie."

This, though, poses the question. If the police and security agencies are self-interested and power-hungry, why do we not see more examples of their corruption, brutality and mendacity? Why have centrists been able to have faith in their good nature?

Simple.It's for the same reason that good parasites keep their host alive. If the police were nothing but corrupt thugs, they would lose their legitimacy and public revulsion at their behaviour would lead to their budget and powers being curtailed. They must, therefore, perform some useful functions to keep the public onside. This practical consideration - which some policemen internalize with a norm of public service - curtails their greatest excesses.

In this sense, we have a glass half-full/half-empty issue. The state and its agents are both iron fists and kid gloves. Statists are apt to forget the former, whilst Marxists and libertarians sometimes under-estimate the latter. But let's be clear that the iron fist (and the grasping hand, to push the metaphor) is always there, and sometimes not only in the background.

June 25, 2013

Of mice and men

Do organizations have an inherent tendency to promote immorality? This is the question posed by a recent experiment (pdf) by Armin Falk and Nora Szech.

They offered subjects the choice: to gas a mouse to death for 10€, or to let it live and get nothing. 45.9% of subjects chose to kill the mouse.

Then, they put other subjects into groups of eight, and gave each individual a choice of A or B. Option A was to let the mouse live and get nothing.Option B was to choose to kill the mouse and get 10€. The subjects were told that if one or more of their group chose option B, eight mice would die. Faced with this choice, 58.6% of people chose to kill the mice. That's a statistically significant 28% more.

The difference, they believe is because of what they call "diffused pivotality." In the second experiment, subjects can convince themselves that they aren't directly responsible for the deaths of the mice, as they can tell themselves: "if I don't choose to kill the mice, someone else will, so I might as well pocket the euros."

In other words, if people can pass responsibility onto others, they are more likely to act immorally.

This is not a new finding. It corroborates Stanley Milgram's famous experiment which showed that people are prepared to give others potentially fatal electric shocks if they believe they are sanctioned to do so by an authority figure. And it has been traditional for organizers of firing squads to put a blank bullet into a gun, so that members of the squad can convince themselves that they fired the blank and so were not responsible for the killing.

These results, say Falk and Szech, "demonstrate the power of organizations to promote immoral outcomes."

But what type of organization? It could be any, for example:-

- In hierarchies, junior members can absolve themselves of responsibility by thinking they are doing what their boss wants.

- In democracies, we might be willing to vote for selfish policies (such as immigration controls?) because we feel our vote won't be pivotal.

- As Steve points out, regulation can actually engender bad behaviour by giving people a "means of neutralization"; responsibility can be passed onto the regulators.

- In markets, people can claim that they are compelled to act badly by the forces of competition. People who sell arms to dodgy regimes commonly claim that if they didn't do so, others would.

Because of self-serving biases, I suspect that people will be quick to pass responsibility to others. However, my hunch is that hierarchical organizations are more conducive than other forms to convincing people that "diffused pivotality" exists and that they are not responsible for outcomes. If this is the case - and several million deaths in the 20th century are consistent with the hypothesis - then hierarchy is, literally, murderously wrong.

June 24, 2013

Meritocracy & justice

"We have been taught that meritocratic institutions and societies are fair" said Ben Bernanke recently. It's a view that seems widely held. In his effort to defend (pdf) the 1% Greg Mankiw suggests that a big reason for increased inequality is that:

Changes in technology have allowed a small number of highly educated and exceptionally talented individuals to command superstar incomes in ways that were not possible a generation ago.

What this view misses is that meritocracy is no evidence whatsoever of the justice of a social system.

Imagine a Stalinist centrally planned economy. The dictator knows that central planning is a difficult job requiring intelligence, skill and hard work. He therefore ensures a system of rigorous exams and hiring to ensure that the best people occupy key positions.

Such a society will be highly meritocratic, in the sense that there'll be a strong correlation between individuals' success - their position in the hierarchy - and their "merit": their IQ, capacity for work or (if you like) the "soft skills" which enable individuals to move up the hierarchy.

Indeed, it's quite likely that this society will be more meritocratic than free market economies, where dumb luck is so important. For example, Jamie Barton got £5000 for winning last night's Cardiff singer of the world contest whereas losers in the first round at Wimbledon get £23,500. It's hard to call this meritocratic, unless you define "merit" circularly as "whatever makes money".

So, is our Stalinist economy just? Not at all. Most of us - including Professor Mankiw I suspect - would argue that it is unjust because nobody should have the power over others which a centrally planned economy gives them.

What made the USSR an unjust society was not that there were deviations from meritocracy, but that there was colossal unfreedom and inequality of power.

This brings me to another point of Mankiw's. He says:

The most natural explanation of high CEO pay is that the value of a good CEO is extraordinarily high.

But our Stalinist might have justified high pay for central planners with the exact same argument: the value of a good planner of the bread supply in Nizhny Novgorod is extraordinarily high.

And in both cases, the counter-argument is the same. It is unjust that any individual has so much power - and, we might add, inefficient too, but that's another story.

The point here is that you just cannot infer the fairness of an economic system from its degree of meritocracy. An unfair system might be very meritocratic - as in my example of an idealized centrally planned economy. And a fair system might be unmeritocratic; Nozickeans would claim this for free societies in which people freely give others' stuff willy-nilly.

The correlation between individuals' "merit" and their individual success is, logically, independent of the question of the justice or not of the basic social structure.

June 23, 2013

Labour & the inflation target

If Ed Miliband really wants to combine fiscal austerity with economic recovery, there's one thing he could do which he didn't mention in yesterday's speech; he could heed Simon's call to raise the inflation target. This would tell the Bank of England to loosen monetary policy to offset fiscal austerity, and help reduce the debt-GDP ratio over time by inflating the debt away - what Duncan calls successful debt management policies. It would have other virtues, described by Laurence Ball.

Why, then, did Miliband not mention this possibility?

One argument against doing so is obviously absurdly inadequate. It's that higher inflation would erode real wages still further. This fails to see that falling real wages are a real, not a nominal problem. Real wages are falling because productivity is falling and because capital has power over labour, not because inflation is high. In fact, looser monetary policy would (subject to caveats I'll come to) actually improve the position by labour by stimulating the economy and improving demand.

Instead, there are three possible counter-arguments:

1. It would raise gilt yields and hence borrowing costs. This is not wholly obvious. Gilts are substitutes for other government bonds, so their yields will stay low if others do, except insofar as a higher inflation target would add to currency risk on gilts. This would happen to the extent that markets believe in PPP, but it's not obvious that they do. It's possible that inflation would reduce borrowing costs if it raises demand for index-linked gilts more than it depresses demand for conventionals.

2. It would raise the savings, as people save more in order to make up for the fact that inflation is eroding the real value of their cash holdings; high inflation in the 70s, remember, was associated with a big rise in the savings ratio. But again, this isn't obvious. Higher inflation and negative real interest rates also reduce the real value of debt. And looser policy would add to housing and share prices, thus generating (arguably!) a positive wealth effect that would reduce the savings ratio.

3. A higher inflation target would be superfluous, because the Bank hasn't got the ammunition to actually increase inflation. Interest rates are likely to be very low when Labout takes power in 2015 - markets are pricing in rates then of only just over 1% - which means the Bank would have very little conventional monetary policy power. This would put a lot of onus upon other policies such as QE or forward guidance (pdf) or the hope of a powerful expectations effect. But the efficacy of these is doubtful.

The case for a higher inflation target is therefore not obvious. But there is certainly, surely, a fruitful debate to be had here. Which makes me wonder why - in public at least - Labour isn't having such a debate. I fear that the desire to look tough and macho is getting in the way of good policy-making.

June 21, 2013

Happiness, relative income & self-interest

"A rise in other people's income hurts your happiness" said Richard Layard (Happiness, p46). "The consumption of the rich reduces everone else's satisfaction" say Wilkinson and Pickett in The Spirit Level (p222). Unusprisingly, then, some believe (pdf) that inequality reduces happiness.

Some new research, however, suggests this needs qualifying. Michael Nolan and colleagues estimate that our peers' income does indeed reduce our own life-satisfaction. But only among the over-45s. Among younger people, higher peers' income is associated with greater happiness*.

This difference isn't because young people are more generously-spirited than oldsters. Instead, it's because of what Albert Hirschman called the "tunnel effect". For a young person, someone else's prosperity is a signal of their own good prospects. For older people, though, others' success triggers unhappiness, as they reflect on the opportunities they missed. Whereas a young person sees a high income and thinks "that could be me soon" an oldster thinks "I could have been somebody."

This helps explain a paradox pointed out by Christopher Snowdon. He notes that people migrate from cities with equal incomes such as Sunderland to unequal London. This, he says, is inconsistent with The Spirit Level's claim that inequality creates unhappiness. But it is entirely consistent with Nolan's finding - because it is young folk who move to That London whilst older ones (such as me!) move out.

There is, however, another paradox here. If differences in relative income make young people (on average) happy and older ones miserable, then you'd expect younger people to favour inequality more than oldsters**. But this is not the case; youngsters, traditionally, are more left-wing than oldies.

Among oldies, the paradox is easily resolved. They internalize inequality, and regard it as their personal failing rather than a social problem. Among young people, however, things aren't so simple. It could be that what we have here is the same thing we see when wealthy pensioners support macroeconomic policies that result in low returns on their savings. People don't always support policies that are in their own narrow interests.

* This is consistent with the fact that oldsters are on average happier than youngsters; income comparisons aren't the only thing that matter.

** Strictly speaking, relative income isn't quite the same as general inequality, as the former is inequality amongst folk of similar age and education, but the overlap is close.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers