Chris Dillow's Blog, page 148

June 20, 2013

On ideology

A better person than me (and everybody else) once said that "culture is what you don’t notice.” The same is true for what is much the same thing, ideology. I was reminded of this by Hopi's proposal that the Independent open a chain of coffee shops on the grounds that Indy readers love their coffee shops.

Now, this is a modest proposal, a doo-dad that slipped into his head. But why, of all the possible ideas one can have, did this particular one slip into Hopi's head, and then onto the page? I suspect it's because of his social democratic ideology.

To see my point, consider what's wrong with the idea. Quite simply, it's that newspapers don't know how to run coffee shops. The Indy won't run coffee shops for ther same reason that Starbucks won't start producing tablets and smartphones even though their customers love them - they don't know how to do so.

But why can't they simply buy in such expertise? They could, but they have no more ability to identify and monitor such expertise than anyone else. For this reason, it is very rare for companies to diversify successfully out of declining industries. They are trapped by their vintage of organizational capital, by their culture.

This poses the question. Why did these objections not occur to Hopi, or to the editor in his head? This is where Hopi's social democratic ideology enters. It stopped him, or his internal editor, from recognizing these objections, in three ways:

1. Social democrats are (too?) optimistic about the limits of knowledge. Just as they think that governments can know enough to regulate industries or to run an effective macroeconomic policy, so they fail to see that managers' knowledge is bounded. Social democrats don't appreciate the force of Hayek's knowledge problem.

2.The managerialist's faith in the portability of management skills. Just as New Labour thought private sector bosses had expertise that could be transfered to the NHS or welfare state, so Hopi thinks the management talent which makes the Indy so well-run is transferable to coffee shops. This is a dubious assumption, challenged by John Pick and Robert Protherough:

The notion that [19th century bosses] had in common a single talent which can be recognised as "managerial skill", capable of ready transference between their different callings, is pure fantasy. That Dr Barnado could equally well have run a chain of newsagents, or that Thomas Cook could just as readily have run a chocolate factory, is manifestly absurd.

Yet the modern world believes as fervently in the transferability of management as it believes that management skills are separate and identifiable realities. (Managing Britannia, p13)

3. The failure to see the importance of path-dependency and organizational culture. For we Marxists, the state is as much iron fist as helping hand, a force which tends inevitably to serve the interests of capital. Social democrats, by contrast, think this history and organizational culture can be changed if only decent people like themselves were in charge.

In these ways, Hopi's ideology prevented him seeing the flaws in his proposal. Ideology reveals itself in the little things, the things that aren't said as well as are said.

Now, you might object to all this that I'm seeing what I want to see here. Maybe. But if my own blog isn’t the place to display the confirmation bias, I don’t know what is.

June 19, 2013

The Bank's scepticism

British capitalism is dysfunctional, and policy-makers have done little since the crisis began to repair it. This isn't (just) my opinion, but that of some monetary policy committee members. Today's minutes show that some thought that:

the benefits of further asset purchases were likely to be small relative to their potential costs. In particular, further purchases could lead to an unwarranted narrowing in risk premia.

For me, this is one reason to favour looser fiscal rather than monetary policy. Fiscal policy can be targeted towards real investment and jobs, whereas monetary policy, especially near the zero bound, has more uncertain scattergun effects.

But leave this aside. Let's ask: given the fiscal stance, is this a good argument against loosening monetary policy*?

Two things suggest not.

First, "narrowing risk premia" is not a bug of QE but a feature. One way in which QE is meant to work - and probably did at first (pdf) - is by encouraging a portfolio rebalancing towards corporate bonds and equities, which reduces firms' cost of capital and thus stimulates capital spending.

Secondly, even if looser monetary policy does lead to asset bubbles, this needn't be catastrophic. For example, the tech bubble burst in the early 00s without serious adverse effects upon output - not least because it wasn't accompanied by large deleveraging or counterparty risk - and it left us with a useful legacy of a broadband infrastructure and some valuable companies.

Why, then, are these considerations weak? The answer could be that MPC members believe two things (or at least attach some weight to them):

- that there's such a dearth of good real investment opportunities that looser monetary policy will instead lead more to malinvestments than to more productive activity.

- that the capacity of the financial system to bear risk is still so impaired that asset bubbles can't deflate without adverse effects.

Insofar as these are the case, then capitalism - in both its real and financial forms - is still dysfunctional. In this sense, MPC members are as sceptical about the functioning of the economy as some of us Marxists.

* I suspect a similar objection could be made to issuing forward guidance, as well as to QE; what's at issue here is monetary policy generally, not the precise form of it.

June 18, 2013

Recession & work ethics

Do recessions have longlasting adverse effects upon output? One common answer is that they do, to the extent that young people who are out of work lose experience and training and so are less productive even many years later. However, in a recent paper Dennis Snower and Wolfgang Lechthaler point to another mechanism through which such hysteresis can occur. Quite simply, unemployment causes otherwise diligent workers to lose their work ethic:

The deterioration of employment prospects during a deep, prolonged recession might induce some elite workers to lose their pro-work ethic. Since identities are sticky, they might keep their new identity even when the recession is long past. In this way, temporary shocks can have permanent effects and thus our model can explain the hysteresis in unemployment observed in many European countries.

This is consistent with evidence that deep recessions do indeed have long adverse effects upon output, and - of course - it strengthens still further the argument for policies aimed at ensuring near-full employment.

However, it bears upon another issue, one which often divides left and right - namely, the extent to which individuals' attitudes (such as work ethic and locus of control) are a cause of economic outcomes or a result of them. In other words, are the sort of people who appear on the Jeremy Kyle show the cause of mass unemployment or the effect?

Snower and Lechthaler's paper suggests the answer is at least partly "effect." In this sense, we can read it alongside Malmendier and Nagel's famous study (pdf) of the longlasting effects on risk appetite of recessions, and the evidence that people who are primed to conform (pdf) to adverse stereotypes really do live down to them.All provide corroboration of Marx's famous claim:

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

June 17, 2013

The policy mix

Should the next Labour government embrace fiscal conservativism as Hopi Sen suggests? I'm genuinely not sure.

Let's start from the premise that, for a given inflation target (or indeed a target for anything else), a tighter fiscal policy must imply a looser monetary policy. Fiscal conservativism thus implies monetary activism. Our question then becomes one of the right policy mix. What are the merits of a tight fiscal/loose monetary policy mix relative to those of looser fiscal and tighter monetary policy?

There are (at least) six considerations here:

1. What's the impact on the exchange rate? The textbook Mundell-Fleming model says a tight fiscal/loose money policy should depress sterling, which those hoping for reindustrialization might welcome. Personally, though, I don't think this is a big issue. Exchange rates rarely move as predictably as models assume, and the link between sterling and exports isn't obviously strong.

2.How close will we be to the zero bound? It's probably fair to say that the impact of monetary policies such as QE is more uncertain than that of ordinary interest rate moves. It is therefore imprudent to be a monetary rather than fiscal activist near the zero bound. I'd be happier with Hopi's policy mix in a world of, say, 5% interest rates than one of say 1% rates.

3.What sort of gilt yields will the next government inherit? Higher borrowing costs mean that a tighter fiscal policy is needed to ensure a stable debt-GDP level. The more the "bond bubble" deflates, therefore, the more reasonable will be Hopi's proposal.

4.What will be the impact on asset prices? Other things equal, a loose money/tight fiscal policy mix is more conducive to asset price bubbles (and therefore bursts) than the alternative. They might, therefore, sow the seeds of the next financial crisis*.

5.What determines capital spending? We all want this to rise. But how to achieve this? If capex is interest-rate senstive, then a tight fiscal/loose money is the way to go. But the very fact that investment has been so weak recently suggests this is not the case. A better way to boost capex might be simply looser policy generally - via a higher inflation target or a level-NGDP target or whatever. This would get the accelerator effect going.

6. What would be the impact on employment? I suspect that properly-targeted looser fiscal policy, such as genuine jobs guarantees, might do more to cut unemployment than loose monetary policy alone.

On balance, this leaves me with an open mind about Hopi's call. I am, though, clear on two things.

First, fiscal conservatism must be coordinated with monetary policy; Hopi's fiscal council will have to work very closely with the MPC. One criticism of George Osborne is that, in keeping the inflation target unchanged for two years, he didn't create enough roomfor monetary activism.

Secondly, Labour's fiscal policy should not be influenced by misplaced calls to apologize for its conduct in office. Economic policy should not be influenced by the post-truth media. But it probably will be.

* It's for this reason that I'm not sure about Simon's claim that, with hindsight, the last government should have run a tighter fiscal policy. Doing so would have reduced interest rates and so created an even greater house price bubble and even more profligate behaviour by banks.

June 14, 2013

Origins of the crisis

The IFS says:

The last decade as a whole was characterised by a very poor performance for average incomes. Between 2002–03 and 2009–10, no single year saw an increase in median income of more than 1.0%.

This reminds us of something I fear is often forgotten - that our economic troubles did not begin with the financial crisis of 2007-08 but rather pre-dated them.

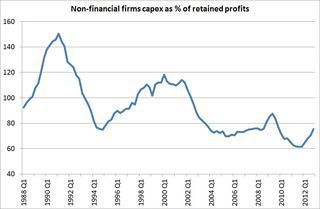

My chart shows this. It shows that firms were loath to invest long before the crisis. Capital spending fell relative to retained profits in the early 00s and stayed very low by historical standards. This reflects the "dearth of domestic investment opportunities" in western economies of which Ben Bernanke spoke in 2005. This is, of course, a cause of the weak income growth of which the IFS speaks; firms' reluctance to spend held down wage and employment growth. The "Great Moderation" might have led to irrational exuberance in financial markets, but it certainly did not unleash a boom in corporate animal spirits and real investment.

In fact, one could argue - as Ravi Jagannathan has (pdf) - that the financial crisis is not the cause of our woes but rather a symptom of this underlying problem. The story goes something like this.

After 1997, Asian economies wanted to run big current account surpluses, either as a policy of export-led growth or in order to rebuild reserves depleted by the 97 crisis. By definition, this meant they were net savers, which put incipient downward pressure upon global interest rates. In a parallel universe, these high savings might have financed a boom in real capital spending in the west. But because firms couldn't see good investment opportunities, this didn't happen.Instead, the lower interest rates fuelled a housing boom and the hunt for yield led to strong demand for mortgage derivatives. These bubbles in housing and derivatives then burst, giving us the crisis.

In this way, we've seen what Marx saw in the 19th century - that a lack of profitable opportunities in the real economy pushes people down "the adventurous road of speculation, credit frauds, stock swindles, and crises."

I say all this as a corrective to a common view on the non-Marxist left - that our economic problems are due to greedy bankers and to austerity. But this is nothing like the whole story. This has been a crisis of real, and not just financial, capitalism - which is why it is so intractable.

June 13, 2013

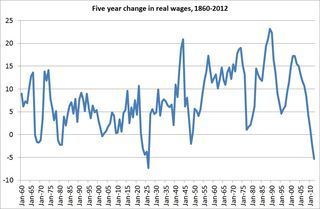

Why real wages are falling

Real wages are falling at a near-record rate. Yesterday's figures show that they were 6% lower in April than they were in April 2008. This is the biggest five-year drop in real wages since 1921-26, and the second-largest fall since records began in 1855.

This cannot be blamed simply on the recession. As the IFS has pointed out (pdf), real wages rose during the recessions of the early 80s and 90s. Something, then, has changed since then. But what?

Here's a theory. Back in the 70s and 80s, bosses could often not efficiently monitor their workers. To keep pilfering and skiving within tolerable limits they therefore had to pay better than market-clearing wages, to buy goodwill. The upshot was that wages rose even during downturns, because bosses feared that real wage cuts would create discontent and thus increase thieving, insubordination and malingering.

This led to a huge literature in economics on efficiency wages, gift exchange (pdf) and insider-outsiders (pdf), which tried to explain high and sticky real wages.

However, as Frederick Guy and Peter Skott have shown, socio-technical change since the 80s such as CCTV, containerization and computerized stock control has made it easier for bosses to monitor workers. Direct oversight means they don't need to worry about buying workers' goodwill. They are instead using the Charles Colson strategy: "When you've got 'em by the balls, their hearts and minds will follow."

Years ago, firms wanted smaller but motivated workforces. Now they can control workers directly, they don't need to worry so much about motivation* and so are content with larger but grumpy workers.

All this has three implications:

1. Talk of "wage rage" misses an important point. At the point of production - to use a quaint Marxian phrase - there is little meaningful rage, because workers can do little to fight falling real wages. (This poses the danger that such rage will find perhaps misdirected political expression, such as in antipathy towards immigrants.)

2. Issues of industrial organization - how firms are organized - have important macroeconomic effects. Macroeconomics cannot be easily studied separately from ind. org. Economists need to look inside the "black box" of industrial structure.

3. You cannot understand economics without understanding power. The fact is that bosses' power has risen and (many) workers' power has declined. In this sense, the rising incomes of the 1% and the fall in real wages for the average worker are two manifestations of the same process.

* except, of course for top-level managers who cannot be directly monitored - hence their rising incomes.

May 29, 2013

Taxes, norms & belief equilibria

Here's another recent finding in experimental economics:

We analyze how tax evasion is affected when the same income is earned without any effort, or with a moderate or high level of effort.We find that subjects who have invested high levels of time and effort evade significantly more taxes.

In other words, people who feel more entitled to their income, by virtue of sweating for it, are more likely to try to keep it.

You might think this unsurprising .But I think it highlights something I've said before - that neoliberalism is performative; it doesn't just describe the world, but creates it.

One claim of neoliberalism is that individuals are entitled to their incomes, as these are the result of work and contribution to society rather than to, say, luck or accidents of history. If people believe this, then they will have lower tax morale, and so will try to dodge taxes either legally or not. The neoliberal claim that higher tax rates reduce revenues will therefore be true. But this will be only so by virtue of people believing they are entitled to their incomes. Neoliberalism then becomes a self-fulfilling belief equilibrium*.

But we can imagine an alternative equilibrium - in fact we don't need to imagine it, as it has existed in some social democratic societies. In this, people regard their high incomes as a product of good luck, and feel obliged to share this fortune. As a result, they tolerate high taxes. In this world, the social democratic claim that high taxes don't reduce effort is true - but, again, only by virtue of people's prior beliefs.

This poses the questions: is it possible to shift the belief equilibrium away from the neoliberal to the social democratic one, and if so how?

It's in this context that we should interpret MPs' haranguing of companies for "immoral" but legal tax-dodging.

From one perspective, such finger-pointing makes no sense; if Labour MPs think companies should pay more tax, they should have changed the law during the 13 years they were in office. However, what they are trying to do is change social norms by stigmatizing tax dodging. This is more than reasonable. It is only by having norms which raise tax morale that higher tax rates can be reconciled with economic efficiency.

Whether MPs alone have the power to change norms is, however, another matter.

* The same might be true for corporate taxes. In a neoliberal world where managers' duty to maximize "shareholder value" is interpreted as narrow short-term profit maximization, we'll see more corporate tax dodging than we would in a world where social norms frown upon agressive tax planning with the result that companies who engage in it alienate customers and so suffer a loss of business.

May 28, 2013

The hollowed middle

What has happened to inequality in recent years? By one standard, it's increased; the share of pre-tax incomes going to the top 1% has rose from 10.4% in 1993 to 13.9% in 2010. By another standard, though, it hasn't much changed lately. Gini coefficients rose sharply between the mid-70s and early 90s but have since moved more or less sideways (figure 5 here).

There's no inconsistency between these two facts. The Gini coefficient measures all inequalities whilst the top 1% ratio measures just one. It's possible, then, for the top 1% to pull away from everyone else without increasing the Gini, as long as inequalities elsewhere in the income distribution are falling.

Which poses the question: if inequality between the top 1% and the rest has risen, in what offsetting sense has inequality fallen?

My table helps answer this. It shows ratios of income to the bottom decile for three years: 1977 (when current data began); 1993, when the Gini peaked; and 2010-11, the latest year available. I'm using two measures of income: original, which is pre-tax incomes from wages, savings and suchlike; and disposable, which are after directs taxes and benefits*.

This shows that between 1977 and 1993 all income deciles pulled away from the bottom two deciles. In 1977, the top decile's disposable income was 5.23x that of the bottom, but in 1993 it was 9.2x.

However, since 1993 these trends have greatly slowed, and in some cases reversed; I'm not sure how far what matters is the level of relative income rather than the rate of change. In terms of original incomes, the top deciles have lost relative to the bottom two. And because the top 1% has gained, we can say that they have also lost relative to the very rich.

However, since 1993 these trends have greatly slowed, and in some cases reversed; I'm not sure how far what matters is the level of relative income rather than the rate of change. In terms of original incomes, the top deciles have lost relative to the bottom two. And because the top 1% has gained, we can say that they have also lost relative to the very rich.

Take, for example, the 6th decile.Since 1993, it's disposable income has barely changed relative to the bottom decile, and it has fallen relative to both the second and top deciles. Much the same is true for the surrounding deciles.

In other words. what we've seen is a squeezed middle, with median earners losing out relative to the poor and very rich. This, I suspect, is due in part to job polarization - the fact that technical change has reduced demand for what used to be moderately well-paid routineish white-collar jobs.

Yes, most people are better off in absolute terms than they were 20 years ago. But we don't compare our incomes merely to those of our 1993 selves. We compare them to our contemporaries. And these comparisons show that the improvement relative to the poor for the middle deciles has more or less ceased since the 1980s, and in some ways it has gone into reverse.

I suspect this is important socially and politically. Politically, it might explain the the increased hostility towards the poor, whom the middling sorts perceive to be a greater threat to their relative position; envy, remember, isn't always directed towards those better off than us. And it might also explain resentment towards the "political class" which has failed to improve the relative position of median earners.

But I have a sense that it's worrying at a broader, social level. Is it really healthy for a society to see a hollowing out of its middle class, with those who are in it feeling threatened by and resentful towards both the poor and the rich?

* Taken from table 16 here, for non-retired households; the disposable incomes are equivalized - that is, they take account of differences in the size of households.

May 27, 2013

On within-class envy

One of the great failures of classical Marxism has been the lack of development of class solidarity. Marx expected the working class to become more conscious of its common interests and thus develop into a powerful political force.But this never happened to the extent that Marxists hoped.

Why not? One possible reason lies in reference group theory. This says that individuals compare themselves to their own social circle rather than to everyone, with the result that we envy colleagues and former classmates who have done slightly better than us rather than the super-rich. This erodes class solidarity.

Some laboratory experiments (pdf) by Philip Grossman and Mana Komai have shown how common such in-group envy is, and how damaging it can be.

They split subjects randomly into two groups - rich and poor, with the rich given a higher endowment and the chance to invest at higher returns than the poor. After a while of investing, and increasing class inequality, subjects were then given the opportunity to spend some money in order to destroy part of another's wealth.

If people were free of envy, they'd never take up this offer as it always impoverished them. But in fact, such choices were quite common. In total, subjects chose to destroy part of another's wealth in almost a quarter of the instances in which they could; 2346 times out of 9600 choices.

However, attacks by the poor on the rich were only a minority of all attacks - 619 of the 2346. Almost as often (509 times), the poor class attacked their fellow poor, with most of those attacks being upon people poorer than themselves. And most of the attacks upon the rich came from other rich folk.

This tells us that there is indeed some inequality aversion; people will pay money to reduce inequality. But this is only part of the story. Folk are also concerned with their individual relative status. So they'll pay money to hold down people who are slightly worse off than themselves, and to bring those slightly above them down a peg or two.

Of course, there are countless real world analogies to this behaviour. Old money sneering at new money, the rich complaining about the super-rich, "white trash" being racist and "strivers" attacking "shirkers" are all examples of within-class conflict. What's striking about this experiment is that such behaviour emerges so easily, without the aid of ideology or media manipulation.This suggests that the lack of development of class solidarity has some deeper-rooted causes than ideology alone.

For a Marxist, this is depressing stuff. But it should also concern any liberal or democrat.It suggests that people might support policies that hurt other poor people - for example, welfare cuts or immigration controls - even if they themselves are harmed by such policies. In this sense, people's preferences aren't necessarily the same as their narrow material interests.

May 26, 2013

What Eton knows

Some people are unhappy that an Eton entrance exam asked candidates to write a speech justifying the shooting of protestors. Their disquiet reflects the discomfort the soft-headed left feels when confronted with the cold hard facts of life.

It is no accident that the question follows a passage from Machiavelli. What we're seeing here is that Eton - the training ground for our future leaders rulers - instinctively understands the nature of power, whereas its soft left critics have always been simperingly naive about it. I mean this in five senses:

1. Political power rests, ultimately, upon force and violence. Plan A for the ruling class is to govern by consent. But there is a plan B.

2. Power comes with risks. If you give bosses power over companies, there's a danger they'll extract wealth for themselves at others' expense. If you give bankers' power over the economy there's a danger of damaging financial crises. And if you give guns to some people and not others, there's a danger people will be killed*. This is something New Labour never really understood. In creating so many new criminal offences and bolstering the power and self-importance of the police, it thought it was acting out of good intentions but was - to take only the latest example of many - merely giving them licence to bully old ladies.Good intentions are not enough.

3. Power depends upon mechanisms. The question rulers must ask is: what tools do we have to exercise our will? Eton knows that one such mechanism is force. Again, though, social democrats have long been naive here. One reason why New Labour was cringingly deferential towards bosses was that it thought that "leadership" was a magic which enabled things to get done, and that the secrets of such ju-ju were known by a priestly elite of "business leaders". But that naivete was nothing new. Back in 1931 a Labour government was replaced by a coalition government which promptly left the gold standard, prompting one Labour politician to bewail "Nobody told us we could do that." Both episodes betray social democrats' ignorance of the tools of power. But Eton's examiners know what the tools are.

4. The role of bad faith. The examiners are not asking for a philosophical defence of killing protestors, but for a speech. The difference is that political speeches need not be true or sincere. The legitimation of power rests partly upon lies and half-truths.

5. Who, whom? Lenin got it right. Power is about who does what to whom? Eton's examiners know that their charges will be the "who" and the rest of us the "whom."

A great thinker - well, greater than most on the non-Marxist left - once asked: "what chance have you got against a tie and a crest?" None at all, given that they know what power is whilst the soft left is just wimperingly emotive.

* I nearly wrote here that there's a risk that power will be abused. But when people speak of the "abuse of power" they often mean what they mean when they speak of "drug abuse" - the routine use of it.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers