Chris Dillow's Blog, page 149

May 23, 2013

On terrorist probabilities

Why aren't the Scots doing more to combat their culture of violence? Why aren't its community leaders doing more to rein in their violent minority? Don't we need tougher laws to protect us from the threat posed by men of Scottish appearance?

You might think I've lost my mind. From a statistical point of view, though, I haven't.

According to table 1.18 of this pdf, there were 89 Muslims in prison for terrorist offences in March 2012 . As there are 2.7 million Muslims, this is 33 per million.

By contrast, there were at the latest count 2382 people imprisoned in Scotland for assault or murder. That's 449 per million.

The prevalence of violent people in Scotland is therefore 13.6 times that of terrorists among Muslims. In fact, this is an understatement. A Scotsman who has committed a violent crime is more likely to be out of prison than a Muslim terrorist, either because he's more likely to have gotten away with his crime or because he's more likely to have finished his sentence.

If it is reasonable to speak of a problem of Muslim terrorism, it is therefore an order of magnitude more reasonable to speak of a problem of Scottish violence.

I anticipate two objections here.

One is that terrorism is nastier than street fights. True.But we must distinguish between the cost of an event and it's probability; I'm talking about the latter.

Secondly, the prevalence of terrorism is greater among Muslims than non-Muslims; Nick Cohen is correct to point out that popular culture misrepresents terrorism in this regard. We can quantify this. There are 29 non-Muslims in prison for terrorist offences. That's a rate of 0.5 per million non-Muslims in the population generally. So, Muslims are more likely to be terrorists than non-Muslims. Coincidentally, the difference between the two groups is about the same (pdf) as that between the prevalence of assault in Scotland and New Zealand - so my analogy holds.

But of course, P(A|B) is not the same as P(B|A). The fact that a terrorist is likely to be a Muslim does not mean a Muslim is likely to be a terrorist. Even if we assume that there are ten terrorists walking the streets for every one inside, then 99.988% of Muslims are not terrorists. To put this another way, there's only around a one in 8000 chance of a Muslim being a terrorist; it's 16 times more likely that the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge will name their child Wayne.

Given all this, why does anyone think terrorism is a Muslim problem? There are several biases at work:

1. The out-group homogeneity bias. Will Davies tweeted that "in my day, a bloke who stabs a random stranger then rants about the government was called 'insane'". This is true if the bloke is one of "us". If, however, he is one of "them" then he is more representative of "them".

2. The narrative fallacy. We love to tell stories and read messages into things, and thus underweight the significance of random nuttery. Frank Furedi says:

One problem with the construction of the random fanatic, is that virtually any form of incomphrehensible act of violence – a school shooting, a crazed knife attack – can be redefined as an act of political terrorism. That is why far too many people cannot resist the temptation of defining the tragedy in Woolwich as an act of political terrorism.

3. The availability heuristic. Dramatic events weigh heavily upon our mind, and this causes us to overweight their probability.

4. Many groups have an incentive to exaggerate the significance of terrorism, and to reframe insane violence as "terrorism." For the police, such attacks give them a chance to further inflate their sense of self-importance and to seize more powers. And politicians can use the image of grave danger and an evil foe to appear Churchillian.

Some things, however, are less significant than they seem.

May 22, 2013

Superstars' baleful effects

Do we over-rate the importance of individual talents to organizational performance? I ask because of this finding by Sander Hoogendoorn:

Team performance exhibits an inverse u-shaped relationship with ability dispersion.

This comes from a study of MBA students' collaborations on business projects. But it is consistent with a finding from baseball, that teams with middling levels of ability dispersion do better than those with low or high dispersion.

It's easy to hypothesise why this might be so. Where's there's middling levels of ability dispersion, less able team members can learn from their superiors. But if there's too much dispersion, they might instead rely too much upon their superstar and shirk responsibility themselves.

Although the only formal study of this hypothesis for football is ambiguous, it is consistent with something Bill Shankly said: "A football team is like a piano. You need eight men to carry it and three who can play the damn thing" - that is, a middling ability distribution. Spurs' sad failure to qualify for the Champions League also corroborates it. They - more than Arsenal or Chelsea - probably have a greater dispersal of ability; the performance gap between Bale and (say) Adebayor is probably larger than than between any two regular Arsenal players*.

All this evidence suggests that relying upon a single superstar is dangerous. There's other evidence for this. Boris Groysberg has shown that the performance of apparently superstar equity analysts declines when they move firm. And many TV shows continue to thrive after the departure of their apparent stars; one of the more significant and forgotten facts of the 1970s was that the Generation Game reached its peak of popularity after Bruce Forsyth left and was replaced by Larry Grayson.

But its not just in important matters such as sport and TV where an excessively lop-sided dispersion of ability can have adverse effects. The same might also be true in politics. The two dominant politicians of our age have been Thatcher and Blair. But under and after their leadership, their parties decayed in both membership, finances and, perhaps, intellectual vigour.

Sure, superstars can sometimes transform a team or organization. But other times, they can serve like Potemkin villages - a healthy facade behind which lies nothing of substance.

* Remember, we're controlling for average ability here.

May 21, 2013

Why pre-tax inequality matters

Does pre-tax inequality matter? I ask because of a dispute between Aditya and Tim. Aditya says that inequality is back at 1920s levels - which is true if we consider the share of the richest 1% - to which Tim replies that the relevant metric is inequality after taxes and welfare benefits:

What we really want to do is measure the distribution after we’ve changed it. For only after we’ve checked how much we have changed it can we decide whether we want to change it some more.

However, I suspect that pre-redistribution inequality does matter.

For one thing, market rewards are linked to the esteem in which we hold ourselves and others; there's a reason why wages are called "earnings." The rich get respect from others and a sense of self-worth and arrogance, whilst those reliant upon "hand-outs" feel despised; this is why the unemployed are so unhappy, even controlling for (pdf) their low incomes. I would have expected a senior fellow of the Adam Smith Institute such as Tim to know this, as this is what the great man wrote:

This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition...[is] the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments...

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments I.III.28)

Mere monetary redistribution doesn't solve this problem. Indeed, it might even exacerbate it, by making the rich feel that they are being deprived of their entitlements in order to support "scroungers". In this sense, inequality can lead to distrust, as Eric Uslaner has written (doc):

When some people have far more than others, neither those at the top nor those at the bottom are likely to consider the other as part of their “moral community.” They do not perceive a shared fate with others in society. Hence, they are less likely to trust people who may be different from themselves.

This matters, because trust is a significant influence upon economic growth.

Worse still, the high opinion the rich have of themselves tends to be shared by politicians. One of the more unpleasant aspects of New Labour was its deference towards bosses which led Gordon Brown to commission endless policy reviews from them, and in the US there's a revolving door between Washington and Wall Street. In this sense, pre-tax inequality of incomes generates an anti-democratic inequality of influence and political power.

But there's another reason why tax and benefits aren't sufficient to reduce inequality. A tax and benefit system does not distinguish between the sources of incomes. An income that is derived from rent-seeking, exploitation or cronyism is taxed as much as one obtained through talent and effort. James Crosby and J.K. Rowling are taxed similarly. But there's surely a difference between them.

Now, you might read all of this as a criticism of Tim. But that's not my main point. My point instead is addressed to the soft-brained left; higher taxes and more generous welfare benefits are nothing like sufficient to tackle inequality.

May 19, 2013

"Swivel-eyed loons"

In the row over the "mad, swivel-eyed loons" remarks, something is being missed - that, from an economists' perspective, we'd expect political activists to be disproportionately mad.

By "mad" I do not mean the content of activists' beliefs, but rather the intensity with which they are held; I'm thinking here of fanaticism rather than extremism. I don't think opposition to EU membership or to gay marriage are mad. What is mad is attaching great importance to such views. As Adam Smith said, "there is a great deal of ruin in a nation." We can live well with a lot of suboptimal policies.

But here's the thing. Political activists are selected for passionate intensity. Stuffing envelopes and canvassing often-hostile voters is a dull and unpleasant way of passing the time. So what sort of people would volunteer to do it? The sort who over-rate the importance of politics - who believe their favoured policies will have huge pay-offs and their opponents' will lead to disaster - that's who. As Eugene McCarthy said:

Being in politics is like being a football coach. You have to be smart enough to understand the game, and dumb enough to think it's important.

I suspect there are two other selection effects:

- When the main parties have so much in common - similar managerialist ideologies - a narcissism of small differences emerges, with both sides exaggerating the benefits of their side and costs of their opponents'. In the 70s and 80s, when there really were big differences between Labour and Tory, it was possible for rational people to think that party politics was very important. It is less possible to do so now.

- Party political activism is now a minority activity. This, I fear, creates positive feedback effects. When party membership was a mass activity, peer pressure attracted sensible people to become activism. Now it is regarded as eccentric, only the eccentric are attracted.

All of this applies to both Labour and Tory parties. But there's another mechanism which makes me suspect that Tories (and Ukippers) are more likely to be loons. If you're a middle-aged, moderately wealthy person working in the private sector, then party politics doesn't much affect you personally: a few pounds here or there on tax rates doesn't much affect the middle classes, but changes to benefit rules can make a huge difference to recipients. The typical Tory activist, therefore, is likely to be someone who over-estimates the importance of party politics.

Now, I don't say all this to claim that all party activists are loons. That phrase "from an economists' perspective" is doing some work; I'm speaking here of cost-benefit considerations and abstracting from the crooked timber of humanity which causes some sane people to become activists.However, these thoughts are consistent with a recent empirical finding - that political activism, unusually amongst voluntary activities, does not make people happier.

May 16, 2013

Adam Smith on immigration

UKIP claims that its tax policies are derived from Adam Smith. But what would the great man make of its anti-immigration policies? I suspect the answer is: not much.

Now, immigration was not much of an issue in Smith's time so he said little about it directly. But he did point out that some forms of migration, such as the settlement of new colonies, greatly increased prosperity. And his argument that import duties encouraged smuggling has an obvious parallel with how immigration controls encourage people traficking. smuggling.

But I'm thinking more of a passage in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (III.I.46 here). He acknowledges that we lack sympathy with foreigners. We would, he says, "snore with the most profound security" upon learning of the destruction of an "immense multitude" of Chinese in an earthquake. But this lack of fellow-feeling must be resisted, he continues. The "impartial spectator", or our conscience:

calls to us, with a voice capable of astonishing the most presumptuous of our passions, that we are but one of the multitude, in no respect better than any other in it; and that when we prefer ourselves so shamefully and so blindly to others, we become the proper objects of resentment, abhorrence, and execration...

One individual must never prefer himself so much even to any other individual, as to hurt or injure that other, in order to benefit himself, though the benefit to the one should be much greater than the hurt or injury to the other.

This, I suspect, is an argument for open borders. It tells us that we must not impose harms upon would-be immigrants, even if immigration is costly to us (which it isn't, but let that pass.)

You might object that by "others", Smith means only other members of our society, or fellow nationals. You'd be wrong. Later on, he writes:

Our good-will is circumscribed by no boundary, but may embrace the immensity of the universe...

The wise and virtuous man is at all times willing that his own private interest should be sacrificed to the public interest of his own particular order or society. He is at all times willing, too, that the interest of this order or society should be sacrificed to the greater interest of the state or sovereignty, of which it is only a subordinate part. He should, therefore, be equally willing that all those inferior interests should be sacrificed to the greater interest of the universe, to the interest of that great society of all sensible and intelligent beings (VI.II.44).

We should, then, read Smith as being a cosmopolitan thinker. Samuel Fleischacker, for example, says "there is no question, I think, that Smith aspired to provide...a structure for morality that reaches out across national and cultural borders."

Such an attitude is surely inconsistent with the little Englander anti-immigrant policies of UKIP.

I say this not simply to point out that UKIP's drawing on Adam Smith is rather selective. I do so to remind readers that Smith was a greater moral philosopher than economist;this passage, for example, is just wonderful.

May 15, 2013

Trends in exploitation

Richard Exell draws attention to figures from the US's BLS, which show that since the early 90s, manufacturing productivity growth in the UK has far outstripped real wage growth. This strikes me as odd. It poses the question: if UK manufacturers have been increasing the rate of exploitation, how come their rate of profit is so low? ONS data show that manufacturers' net return on capital was 4.7% in 2012, way down from 15.8% in 1997, when the ONS's present records began.

One reason is that the capital-output ratio has increased. Another is that manufacturing prices have not risen as much as consumer prices; since 1996 (when ONS records began) producer prices have risen 31.6% whilst the CPI has risen 43.4%. This has driven a wedge between the real wage as experienced by manufacturing employers, and that as experienced by workers.

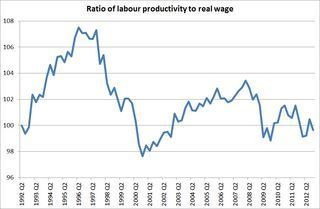

In fact, there is a different set of data which paints a very different story from the BLS, shown in my chart.

This shows labour productivity for the whole economy - defined as GDP per employee* - and real wages**, as deflated by the GDP deflator at basic prices; this is the real wage as experienced by employers, rather than employees. The data starts in 1992 because that's when ONS data on employees begins.

This shows a cyclical pattern in the rate of exploitation. Productivity rose faster than real wages in the early 90s, more slowly in the late 90s, faster in the early 00s but has since fallen. The rate of exploitation is about the same now as in the early 90s. This is consistent with the trends in wage and profit shares during this time.

This is a very different picture from the BLS's numbers, not least because productivity in the whole economy has grown more slowly than it has in manufacturing - by 37.5% between 1992 and 2011 in my data against 78.7% in the BLS's.

This poses the question: if the rate of exploitation hasn't increased much lately, why are wages squeezed?

Two reasons. One is that productivity has fallen since late 2007, so the pie is smaller for both capital and labour. Another is that, thanks in part to rising VAT, the prices experienced by workers have risen faster than the GDP deflator - by 17.8 per cent between 2007Q4 and 2012Q4 against 9.3% for the deflator.

I do not say all this to deny that workers are exploited. They are; anyone who thinks you have to believe in the labour theory of value in order to claim this should be hit repeatedly with a copy of Roemer's Free to Lose. But we should distinguish between this fact about the general nature of capitalism and the cyclical problem of depressed real wages, which has little to do with an increased degree of exploitation.

* ONS code identifiers CGCE divided by MGRN

** This is defined as total employees compensation divided by the number of employees: identifiers DTWM and MGRN, divided by CGBV

May 14, 2013

Tax incidence: left responses

Can social democratic policies reconcile capitalism with leftist conceptions of social justice? This is an old question which I ask because of a new paper which finds that, in Germany:

a 1 euro increase in [corporate] tax liabilities yields a 77 cent decrease in the wage bill.

This, of course, adds to the literature which shows that the incidence of company taxes falls heavily upon workers, in the form of lower wages and employment.

Which poses the question: if taxing profits is infeasible, what policies would increase equality?

It's not not enough for the left to contend that non-financial firms are sitting on massive cash piles - of £315.9bn deposits with UK banks and £383.9bn with overseas ones*. If firms don't want to invest at low tax rates, it's difficult to see how they'll do so at higher rates**. This leaves two possibilities.

One is to shift the tax base from profits to land value. However, whilst this is technically a good idea, I'm not sure how politically feasible it is. One reason why local government lacks any real autonomy is that the property taxes needed to finance it are so unpopular. Business rates are loathed, whilst domestic rates were so hated that Thatcher abolished them.

Another possibility is to shift taxes onto individuals. Personally, I suspect higher personal taxes are more technically feasible than generally thought, but I fear I'm in a minority.

This leaves a third possibility - to abolish capitalism and profits. Granted, nationalizing companies so that the state can grab their profits might be like buying an airline to get free hot towels. But I suspect that worker-owned firms would provide a more stable tax base than profits do now. If workers owned firms, they could no more enrich themselves by shifting the burden of profit taxes onto workers than they could by moving their wallets from their left-hand pocket to the right-hand one.

I mention this last possibility not because it is politically feasible, but to pose a question: what if "tax justice" can only be achieved by abolishing capitalism? I fear that social democrats avoidance of this question owes more to wishful thinking than it does to a firm evidence base.

* Table A57 of this pdf.

** It is theoretically possible to tax firms on their cash holdings rather than profits. But we know this isn't sufficient to raise investment because we've tried it since 2009. Falling (and negative) real interest rates are in effect a tax on cash, and whilst these have probably prevented capital spending falling more than it has - through mechanisms other than merely reducing companies' opportunity cost of holding cash - it has not unleashed a great boom.

May 13, 2013

Changing attitudes

What function do, or should, left-wing parties serve? I ask this old question because of a paper which Jon has drawn my attention to.

Peter Taylor-Gooby points out that, as inequality has risen, attitudes towards the poor and benefit recipients have hardened.He suggests several longer-term reasons for this, among them the decline of class alignment and rise of individualism. I'd add three other factors:

- A mistaken factual base. The public under-estimate bosses' pay and over-estimate welfare benefits.

- Recessions usually make people more mean-spirited.

- Capitalism generates cognitive biases (ideologies) that result in hostility to welfare recipients.

As Taylor-Goody says, it doesn't need to be this way: "Alternative approaches that emphasise reciprocity, solidarity and inclusion are possible."

This poses the question: how do we get to such approaches from where we are? One possibility is to look to a leftist party to argue for them. But there are good reasons to expect the Labour party not to do this. Just as companies' marketing strategies rarely work by telling potential customers they are stupid, so political campaigns rarely do so. This is why Labour panders to some of the worst aspects of public opinion, on immigration or welfare, rather than outrightly opposes it. The Labour party is a managerialist marketing strategy, not a force for truth and justice.

But if Labour is not an agency for radical change, what is? Sure, there are a few bloggers and columnists who are trying to shift the Overton window, but these tend to preach to smallish groups of the already-converted.

This, of course, is not to deny that social attitudes can change. For example, during my lifetime, attitudes to gays has improved considerably. But I fear that this progress has been like Max Planck's view of scientific advance - it has happened one funeral at a time.

And herein lies a paradox of the left. Whilst we have spent decades advocating social change, we have remarkably few answers to the question: through what mechanisms, exactly, can it be achieved?

May 10, 2013

The cost of policing borders

Tim and James agree that it is stupid to penalize landlords who rent property to illegal immigrants. I'm not so sure.

The virtue of such a policy is that it increases the salience of the cost of policing immigration, and so it could increase opposition to closed borders.

And this cost is already significant. The UK Border Agency cost £2.3bn to run in 2011-12. And those who think illegal immigration is a problem presumably think this sum was insufficient.

But £2.3bn is equal to almost half of spending on Jobseekers Allowance in 2011-12.

Let's put this another way. There are now 463,000 people who have been unemployed for over two years. Let's assume half of these are "scroungers" who could - if they wanted - find full-time minimum wage work. (I think this is an absurd over-estimate of their chances of getting work, but humour me.) How much would this save the tax-payer?

We'd save JSA of £71.70 per person per week. That's £865m. These people would also pay just over £1200 a year in tax and NI, which saves the Exchequer another £300m. There'd also be a saving in housing benefit. Let's call this £400 per person per month (the rent on cheap one-bed flats in Leicester) which is £1.1bn. This gives us just under £2.3bn.

In other words, the cost to the tax-payer of policing our borders is roughly the same as a generous estimate of the cost of "scrounging."

You might object that policing the borders saves the taxpayer money to the extent that immigrants would be a drain on the welfare state. You'd be wrong. Most estimates show that immigrants are a small net benefit to the Exchequer.

Personally, I think these sums are small. They are less than 0.2% of GDP, and there's a lot of ruin in a nation. The biggest costs of border controls are the loss of liberty, the reduced welfare of would-be immigrants and the economic benefits we forego.

However, my point is that anyone who is annoyed by the cost to the tax-payer of "scroungers" should be irked to a roughly equal extent by the cost of border control.

But I get the impression that very few supporters of UKIP or the Tories are. Which makes me suspect that what's at issue here is not a narrowly rational calculation of fiscal costs and benefits.

May 9, 2013

Sir Alex, & a dying culture

Rob Marrs says something true and important:

Ferguson has more in common with the likes of Busby, Stein, Shankly and Paisley than he does with most of today's managers.

This hints at a significant fact about the truly great managers in British football - that they were socialized into a collectivist culture. Very many - Stein, Shankly, Busby and before them Herbert Chapman - came from mining communities and almost all others such as Ferguson, Cullis or Revie from classic northern working class backgrounds.

I stress that word "culture" because I'm referring to something deeper than trivial political beliefs - although it's no coincidence that so many great managers from Clough and Stein to Ferguson and Wenger have had socialist sympathies.

I don't think Jose Mourinho represents a counter-example here, as he was brought up under a different form of collectivist culture, that of Portuguese fascism.

As for why this should be, there might be a selection effect. Opportunities for bright lads from working class backgrounds are limited, so football management is one of the few ways in which exceptional men can achieve prominence.

But there's something else at work.It's that a collectivist culture is necessary to build a team; a team is not about 11 individuals, and a working class (or Fascist!) upbringing inculcates a belief in collective effort. Here's Mourinho:.

I hate to speak about individuals. Players don’t win you trophies, teams win trophies, squads win trophies.

Here's Shankly:

The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That's how I see football, that's how I see life.

And here's an account of Revie at Leeds:

Revie also created brotherly spirit among the squad. 'Our whole ethos was built on loyalty,' Lorimer says. 'We all fight for each other, we all work for each other. If someone kicks me, he kicks all 11 of us.'

I say all this for three reasons.

First, this suggests a reason why top English football managers are so scarce; the collectivist culture which contributes to their success has disappeared. Remember, no Englishman has managed a title-winning team since 1992, and none born south of the Trent has done so since Alf Ramsey in 1962.

Secondly, all this hints at a colossal waste of talent not just years ago but perhaps even today. How many people from poor areas had intelligence and organizational skills like our great football managers, but lacked the opportunities to exercise them?

Thirdly, if a collectivist mindset is conducive to success in football, why should it not be so in other organizations? Most company managers come from a very different culture from our great football managers. Could it be that, because of this, they are missing something? Yes, Harvard Business School has made a case study of Sir Alex. But is it possible to teach what he knows? Or is it that his success rests in part upon the tacit knowledge embedded into a culture which has largely died out?

A caveat: Bill Nicholson might be an exception here, as he played for the Young Liberals in Scarborough. But he managed S***s, so can be discounted.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers