Chris Dillow's Blog, page 153

March 29, 2013

In (half) defence of New Labour

Hopi hopes that New Labour will rise from the dead. I half-hope he's right. New Labour was not just empty slogans, infighting and invading Iraq. It was a serious supply-side economic project - an attempt to answer big problems. For example:

- The emphasis upon education, including Sure Start, was intended to address the fact that demand for lower and middlingly-skilled workers was falling, whilst that for more skilled ones is rising.

- Brown's attempt to provide a stable policy framework - for example through Bank of England indepedence - was intended to reduce some of the uncertainty that businesses face, and thus stimulate investment.

- Public sector reform was intended to ensure that taxpayers get more bangs for their buck.

I would rate New Labour a failure. It had far too much faith in managerialism and not enough in bottom-up workers control, and thus was blind to the damage done by arrogant management. It under-estimated the importance of the dearth of investment opportunities in the west and thus over-estimated the underlying vigour of capitalism. And public sector reform requires a more delicate touch than some New Labourites imagine, to ensure that the right incentives are created without impairing the knightly (pdf) motives of public sector workers.

Nevertheless, its policies were not wholly without good intellectual (pdf) foundations. And the questions it raised are still important: what to do about falling demand for less skilled workers? How to raise investment? How to raise public sector productivity?

Like Hopi, I fear that the left's opposition to austerity is distracting it from the fact that there must be more to economic policy than just Keynesianism. Yes, New Labour got the answers wrong. But it got the questions right. The problem is, a lot of the left aren't even asking those questions.

March 28, 2013

Miliband's message

I tweeted last night, to the consternation of some, that David Miliband is one the the nicest blokes I've met. I did so for three reasons, other than that it's true.

First, to counter a couple of common cognitive biases. One is a form of the halo effect - the idea that because someone has bad politics, he is a bad person. This is just wrong. Sometimes (often) bad people do good things, and good ones bad things. The other is a form of outcome bias. Peter Oborne describes David as "greedy", but he never struck me as that at all. Just because someome is rich does not mean they are greedy. They might instead be just lucky, in the right place at the right time.

Secondly, and relatedly, I want to counter a common conception of politics, especially on the left. It's what I've called the Bonnie Tyler syndrome, of holding out for a hero - the idea that our political objectives can be achieved if only we could be governed by the right people. But this is not true. It ignores the power of capitalism to perpetuate itself, for example because it generates ideologies that favour inequality, and because capitalists' control over investment decisions gives them control over the economy. And it ignores the fact that even quite senior politicians have less influence than is attributed to them; as I've said, office doesn't just corrupt, it enslaves.

We pay too much attention to the character of politicians, and not enough to the power structures and ideologies that constrain them.

Remember - David did have radicalish instincts. In 1994, for example, he described inequality as "shocking" and pointed out that "capitalist economies contain basic inequalities of power."

Thirdly, I did not mean "nice" entirely as a compliment. One fault of agreeable people is their tendency to trust others too much, perhaps because they wrongly project their own decency onto them. I fear this tendency led David to become too trusting of Blair.

The message of David's career, then, is that good instincts, decency and intelligence are not enough for a politician to change society. It is an old joke that Ralph Miliband thought that socialism couldn't be achieved by parliamentary means, and his sons are proving him right. But there's an element of truth in this.

March 27, 2013

Why is the middle squeezed?

Hopi points to the paradox that whilst some of the left is talking more stridently, actual trades union militancy, as measured by strikes, is very low. A new paper highlights this disjunct between the political and industrial spheres.

Martina Bisello shows that there has in recent years been a job polarization; employment has grown in both well-paid and badly-paid jobs at the expense of middling occupations. She attributes this to the IT revolution which, along with other technical changes, has had three effects:

- it has displaced routine white-collar clerical workers.

- it has increased demand top-level employees who analyze and manage data.

- in permitting direct control of many manual workers, it has reduced the efficiency wages these receive, and this relative wage fall has helped sustain demand for such employees.

I recommend the work of Peter Skott and Frederick Guy on power-biased technical change in this context.

[image error]

Granted, this process hasn't all been bad for middle-income earners, as many, like Joan Harris a generation earlier, have moved up the occupational ladder. Nevertheless, it suggests that the squeeze on middle incomes has a basis not just in the macroeconomics of stubborn inflation, but in changes in the technical-industrial base.

This fact, however, is scrupulously ignored by the Labour leadership, which thinks of the "squeezed middle" as a purely political rather than industrial problem. To paraphrase Marx, Labour inhabits the "very Eden of the innate rights of man" that is the sphere of commodity exchange, and never troubles itself to consider the "hidden abode of production". The industrial and the political realms are thus separated.This surely represents a triumph of the Thatcherism which asserted "management's right to manage".

And herein lies my concern. Marx was surely correct to point out that a strategy that never inquires into the hidden abode of production is unlikely to succeed intellectually. So can it succeed politically?

March 26, 2013

Immigration & irrationalism

Britain has an immigration problem - but not of the sort generally supposed.

Let's be clear. The facts show that immigrants are a net fiscal benefit rather than a cost, and that immigration is, except for a small negative effect at the bottom end, a net positive for wages (pdf) and for economic growth (pdf).

Economically speaking, then, immigration is (net) a good thing.

So, what's the problem? It's that the public just don't believe the economic evidence. I don't think this is simply because they hold economists in low esteem: the man on the Clapham omnibus does not devote his waking hours to thinking "that Jonathan Portes talks some shite." Rather, I suspect the problem is a more general one - that irrationalism plays a big role in human affairs.

There's an analogy with the MMR scare of a few years ago. The idea that immigration is an economic problem is like the belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism. Both views are founded upon a mix of anecdote and the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy: "my son got the jab and then was diagnosed with autism"; "a lot of Latvians arrived in town and my son now can't find a job." And in both cases, scientific evidence is weak against vivid anecdotes and well-organized campaigning.

You only have to listen to 6-0-6 to know that opinion and evidence coincide only accidentally. The belief that migrants are a drain on the economy is like the popularity of Boris Johnson, homeopathy or conspiracy theories.

It would be easy - and right - to complain that politicians and the media amplify such irrationalism rather than challenge it.

But there's a caveat here.Irrationalism is not wholly unreasonable.Yes, the belief that immigration is doing serious economic damage is wrong, as it lacks a good evidence base. But an uneasy feeling that change can have unforeseeable effects isn't so stupid, being rooted in a reasonable conservative disposition - and in the fact that, as Diane says, there's much we don't know about the effects of immigration.

One way to combat this instinct, as I've said, is to remind people that immigration is nothing new and is part of our "island story."

But there's something else. We know from financial markets that risk aversion rises in bad times, and falls in good. This is one reason why, as Ben Friedman has shown, people become more intolerant in recessions - it's because downturns cause them to see the downside of change, openness and diversity more than the upside. Perhaps, then, an economic recovery would soften attitudes to immigration - although it'll take more than this to convert people to the case for free migration.

March 25, 2013

Marriage & wages

Bryan Caplan says the marriage premium (pdf) - the well-established fact that married men tend to earn much more than single ones - is due in large part to causality. Being married, he says, causes men to earn more, rather than there being selection effects, whereby men who are attractive marriage prospects are also attractive to employers. Several things make me agree with him.

- Introspection. I strongly suspect that if I'd been married, I would have earned more. This is partly because a wife might have inspired me to overcome my distaste for job search, and partly because having someone to provide for would have caused me to move along the wage/job dissatisfaction indifference curve. It's also plausible that a wife can nag a man to get a job.

- The marriage premium is bigger for straight men than gays (pdf). This is not obviously consistent with selection effects; if it were the case that the same things that make a man attractive to an employer also make him marriageable, shouldn’t this effect be as powerful for gays as straights? It is, however, consistent with a causal effect. Having a wife frees a man from housework, thus allowing him to focus on his job, and gives him a chance of having children for whom he must provide.

- Top baseball players earn more if they are married. Again, this is inconsistent with selection effects; most such men are surely highly marriageable. But it is consistent with a causal role. Maybe employers discriminate in favour of married men, believing them to be more reliable. Or maybe a wife emboldens a man to take a more aggressive stance in wage bargaining.

- Even a study which favours the selection hypothesis finds that there's a causal effect at the lower part of the wage distribution.

However, on the other hand, something else leads me to favour the selection effect. It comes from happiness research. There's good evidence that married people, on average, are happier than singletons. However, Andrew Clark has shown that the effect on happiness of marriage fades away quite quickly. How can we reconcile these facts?

Simple. Happier people are more likely to be married; who wants to marry a miseryguts? Marriage doesn't cause happiness, but it selects for it.

And here's the thing. There's evidence (pdf) that happier people earn more (pdf) than less happy ones.

Perhaps, therefore, the positive link between marriage and wages (for men) isn't wholly causal, but reflects the fact that happiness increases both wages and marriage chances.

If all this sounds like an abstruse issue of labour economics, it shouldn't. There's an ideological undertow here. Bryan thinks that poverty (in the US) is due to individual bad behaviour, and so changing behaviour "get married!" is a route out of poverty. His interlocutors, however, disagree.

However, we must avoid the trap of motivated reasoning. The marriage premium is causal or not, whether you want it to be or not. I suspect that some of it is causal. But this doesn't mean I have to accept that poverty is simply due to individuals' failings.

March 23, 2013

Asymmetric libertarianism

Katie Price and UKIP agree that benefit recipients should not spend "our money" on booze and ciggies. A little thought, however, reveals that such spending is in fact puny. Let's do the numbers.

The DWP says that, in 2011-12, working age people got £52.7bn in benefits. Of this, £16.6bn was housing benefit and £2.7bn council tax benefit, so benefit recipients saw £33.4bn. This is 2.2% of GDP, and 5.2% of total government spending.

What fraction of this £33.4bn is spent on drink and ciggies? We can use table A6 of the latest Family Spending tables as a guide. These show that the poorest decile spend an average of £148,80 per week on non-housing. Of this, £2.70 per week (1.8%) goes on alcohol and £3.90 (2.6%) on tobacco and narcotics. If we apply these proportions to the £33.4bn of benefit income, then £606m of those benefits are spent on alcohol and £875m on tobacco.

But the government gets a lot of this money back in VAT and excise duties - about £689m on tobacco and £190m on alcohol. This implies that benefit recipients' spending on tobacco and alcohol costs taxpayers a net £602m. In fact, not even this much, to the extent that brewers and tobacco manufacturers pay tax on their incomes.

This is a tiny sum. It's 0.09% of public spending and 0.04% of GDP. In making an issue of this, Ms Price is enlarging things out of their proper proportion.How unlike her.

What's going on here? Usually, I'd quote C.B.Macpherson, to the effect that there's still a puritan strand in politics which regard poverty as a moral failing and the poor as objects of condemnation. However, considering Ms Price's career, puritanism is hard to discern.

Instead, I suspect what we see with her and with Ukip - and, one could argue, with some who support press regulation whilst favouring social liberalism in other contexts - is asymmetric libertarianism. People want freedom for themselves whilst seeking to deny it to others; this is why some Ukippers can claim to be libertarian whilst opposing immigration and gay marriage. This debased and egocentric form of libertarianism is more popular than the real thing.

March 22, 2013

Inequality, evolution & complexity

Why has mainstream neoclassical economics traditionally had little to say about the causes and effects of inequality? This is the question raised in an interesting new paper by Brendan Markey-Towler and John Foster.

They suggest that the blindness is inherent in the very structure of the discipline. If you think of representative agents maximizing utility in a competitive environment, inequality has nowhere to come from unless you impose it ad hoc, say in the form of "skilled" and "unskilled" workers.

But there's an alternative, they say. If we think of the economy as a complex (pdf) adaptive system - as writers such as Eric Beinhocker, Cars Hommes and Brian Arthur suggest - then inequality becomes a central feature. This is partly because such evolutionary processes inherently generate winners and losers, and partly because they ditch representative agents and so introduce lumpy granularity. Markey-Towler and Foster write:

Inequality is a phenomenon that should arise naturally in a complex, networked economy as value‐generating connections (transactions, business relationships etc.) are formed, consolidated and broken. Concentrations of market power, skill differentials, luck and rent‐seeking can all be dealt with in such an analytical framework.

This is a point touched on by Ben Fine in a paper (pdf) claiming economics is unfit for purpose.He cites some econophysics research which shows a few dozen multinationals control the world's economy.

If you think that's a bit Bilderbergian, consider this new paper by Pablo Torija. He shows how, since the 1980s, western politicians have stopped maximizing the well-being of the median voter, and have instead served the richest few per cent.

If the economy is an adaptive ecosystem, it is one in which a few predators are winning at the expense of the prey.

March 21, 2013

Mortgage guarantees as deficit reduction

I tweeted yesterday that the government's mortgage guarantee scheme could be a deficit reduction strategy, to which Andrew Lilico responded sceptically. I should expand.

In one sense, Andrew's right.The scheme (pdf) increases the government's contingent liabilities; it might have to pay several billions if those guarantees are exercised. In this sense, the government's off-balance sheet debt has risen; Osborne has learnt from the last Labour government, and not from US experience*.

So how can I say the scheme will reduce government borrowing? Let's assume the plan does what it is intended to do, and so someone takes out a £100k mortgage they would not otherwise have taken.

This mortgage, however, is someone else's asset; the person selling the house gets an increase in their bank deposit.

Now, if this is all that happens, Andrew is right. The aggregate financial balance of households has not changed, so there is no reason why any other sector's financial balance should change.

But is this all that happens? Not necessarily. If the seller spends some of the proceeds on consumer goods, then households' aggregate financial balance declines, because the seller's bank deposits don't rise one-for-one with the mortgage. Another sector's financial balance must therefore increase. And this would be at least partly the government's, to the extent that its gets tax revenues from the home-sellers purchase of goods.

The same thing would happen if the rise in house prices caused by the extra demand might cause other homeowners to borrow more to fund consumer spending, either because their collateral has increased or simply because they feel richer.

There's another possibility. Increase mortgage demand might encourage housebuilders to build more. This would mean they run down their cash balances as they buy materials and labour. This might reduce the corporate sector's aggregate financial surplus, depending on what materials' sellers do with the revenues. The counterpart to which would be an improved government financial balance - say, because of higher corporate taxes from materials' sellers.

These were the sort of mechanisms I had in mind. How might Andrew be right? One channel would be if the home-sellers, being currently highly geared, merely use the proceeds of their sale to pay off their mortgage and trade down. Another possibility would be if rising house prices cause people who'd like to buy a house to save more for a deposit; as Willem Buiter has said, housing isn't net wealth.

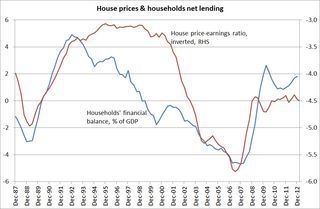

In theory, then, either Andrew or I might be right. My chart, however, suggests the odds favour me. It shows that there has historically been a correlation between house prices and households' financial balance. High prices, such as in 1988-98 and the mid-00s were associated with households' financial deficits, and low prices with surpluses. This makes me think that encouraging mortgage lending and raising house prices will increase households' aggregate financial deficit.

Now, accounting identities mean that if one sector has a higher deficit, another must have a higher surplus or lower deficit. There are only three possibilities here:

- Foreigners run a higher surplus, because the additional household borrowing is spent on imports. But the marginal propensity to import is less than one, so this isn't the whole story.

- The corporate sector's surplus rises. This would happen if housebuilders simply pocket the proceeds from additional house sales and don't reinvest them. If this happens then Osborne's hope of encouraging housebuilding will have failed.

- The government's deficit will fall, say because the extra spending associated with the declining household surplus brings in tax revenue. If Osborne's scheme works at all as he hopes, this must be at least part of the story.

* Fans of 1970s comedians might claim he's paid more attention to Balls than Fannie.

March 19, 2013

The lump of rationality

Tim points to Brian Cox's claim that "engineering is the foundation of our economy" as corroboration of Richard Feynman's quip that "a scientist looking at nonscientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy."

This, I suspect, reflects a general psychological fact - that many of us have a "lump of rationality", such that if we use a lot of it in one activity, there's little left in another. People who are rational in some contexts can be irrational or downright barmy in others. Vicky Pryce is perhaps an extreme example of this, but many would add Richard Dawkins, and I guess you can all think of other less famous examples.

There are good reasons why this might be:

- Ego depletion. Our willpower is limited, so if we use it in one context, we lack it in another. This is why men often get drunk after a hard day's work, why people put on weight when they give up smoking, or why women on diets go on spending sprees. A similar thing applies to thinking. Rationality requires effort, so if we use it in our day job we don't have much left elsewhere.

- Incentives. In Professor Cox's day job, irrationality will cost him heavily; his papers won't be published and he'll not get funding or promotion. But his political opinions are a free hit; stupidity is not penalized in politics. Simple incentives, then, mean that Cox - and indeed many professionals - will be more rational in their day job than in their political opinions.

- Motivated reasoning. We often think most clearly when we have no skin in the game, no interest at stake. But this is almost never true for all domains. There's always some interest to promote (science teaching in Cox's case or hating Huhne in Pryce's) or some opinion to bolster (atheism for Dawkins), and this leads to poor judgment.

- Other objectives. Human history surely teaches us that decisions made at two in the morning are rarely fully rational. However, political agreement is often reached then - look at many EU summits or this week's agreement on press regulation. Taking decisions at stupid o'clock might be irrational in the sense of not fitting the facts or not leading to the most efficient policy. But these are not the objectives. Sometimes, rough compromise and collegiality matter more than cold-headed rationality.

This last point is under-appreciated. A while ago, I was in a long queue in a greengrocers in Belsize Park, behind a man who was taking an eternity to choose some plums. When he turned round, I gave a cry: "fuckin' 'ell, it's Mike Brearley." Mr Brearley was committing the error of not seeing that, sometimes, any decision is better than the rational one. Jon Elster quotes Boswell on Samuel Johnson:

He did not approve of late marriages, observing that more was lost in point of time than compensated for by any possible advantages. Even ill-assorted marriages were preferable to cheerless celibacy.

Perhaps, then, it is not only impossible for us to be fully rational, but undesirable too.

March 18, 2013

Power matters, Cyprus edition

It's widely agreed that the EU's plan to penalize smaller depositors in Cyprus's banks is a terrible idea, because as Paul Krugman says:

It’s as if the Europeans are holding up a neon sign, written in Greek and Italian, saying “time to stage a run on your banks!”

But if it's such a bad idea, why do it? The answer lies in something known by Marxists and heterodox economists, but which orthdox economics still has trouble acknowledging. Quite simply, the allocation of wealth, or costs, depends upon power.

Let's put it this way. Who could pay for Cyprus's insolvent banks? The answer isn't their bond-holders, because these are almost non-existent, and nor is it shareholders, as even a 100% loss for them doesn't cover the banks' liabilities.

In principle, Cyprus's government could have bailed out the banks. But this would have left it insolvent, requiring a bail-out itself. That would have imposed losses on holders of Cypriot government debt, such as European banks and hedge funds. But such holders had the power to resist this - in part because of the credibleish threat that such losses would have weakened confidence in the general European financial system, and as Kalecki said, "confidence" is one of the tools whereby capitalists retain power over the economy and governments.Pawelmorski says:

The hedge funds win again. A favourite trade for speculators has been Cypriot government debt. And it’s done very nicely. Mayfair sends its thanks.

This leaves only two possible payers. One is German tax-payers. But these have the obvious bargaining power of having little to lose if no agreement is reached.

The other possibility is that larger depositors in Cyprus's banks pay more - these being Russian gangsters legitimate businessmen and Greek tax-dodgers. But naturally, the rich have the power; the joke that Cypriot president Nicos Anastasiades "has only rich friends" gains power from its plausibility.

As a matter of elimination, therefore, smaller depositors - those who supposedly had a "guarantee" must pay. They do so not because of any principle of fairness or efficiency, but because they lack the power to protect their interests. What we're seeing here, says Pawelmorski, is "a cruel piece of realpolitik."

One quirk here is that its possible that these haircuts are a backdoor way of channeling Cyprus's large gas reserves into Russian hands. This, of course, in no way undermines my point, which is that economic allocations are determined by power.

My point here is not just about Cyprus. It's about economics generally. If we cannot understand Cyprus's situation without thinking about power relationships, why should we assume that we can ignore power in other aspects of economics, such as the everyday transactions that have led to rising inequality?

The answer, of course, is that we can't. Power matters more than fairness or efficiency. It's about time conventional economics cottoned onto this.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers