Chris Dillow's Blog, page 156

February 24, 2013

The irrational virtue of stubbornness

Arsene Wenger and George Osborne don't seem to have much in common - only one of them has a qualification in economics - but they do. Both this week expressed a will to stay the course despite criticism. Osborne says that Moody's downgrade merely "redoubles" his determination to stay with his plan, and Wenger says he has never for "one second" considered resigning.

Such stubbornness is, of course, common in many walks of life. It is often the product of many cognitive biases, such as:

1. Bayesian conservatism. Both Wenger and Osborne have strong priors that they are right, and they regard evidence to the contrary as sufficiently noisy that it can be disregarded.

2.Ego involvement.For either man to step down would be a recognition not merely that a set of intellectual propositions is wrong, but that they themselves are not the men they thought they were - not the great Chancellor or great coach.

3. Gratification of enemies. An acknowledgement of error would be a victory for things they hate - Ed Balls in Osborne's case and financial doping in Wenger's. It's one thing to admit error in oneself; it's another to surrender to a loathsome foe.

4. Wishful thinking and overconfidence. It's surprisingly easy to believe things will turn out to one's advantage, especially if you think you're right anyway. So Osbone thinks business confidence will pick up because of low interest rates, and Wenger thinks his players will improve and that he can find new players to strengthen the squad.

It seems, then, as if Wenger and Osborne have much in common. Except for one thing - Wenger is a genius and Osborne, well, might not be. The difference, I suspect, lies in point 1. Wenger's prior that he knows best is founded upon things like: the fact that he's the only coach in 130 years to have taken a team through a whole top-division season unbeaten; the fact that no team that cost less to assemble has finished above Arsenal; and that he has turned countless players from unknowns to world stars. Osborne's prior is somewhat less well-founded.

Yes, Wenger might be biased. But sometimes, cognitive biases are a good thing, as they give us the strength to stick with a correct course in the face of adversity. The author who gives up after a few publishers reject her work, the businessman who gives up after a bank turns him down or sale falls through, and the musician who gives up after a few bad gigs might be behaving rationally. But rationality is not necessarily the road to success. As Richard Nisbet and Lee Ross wrote in Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgement, one of the earliest books on cognitive biases:

We probably would have few novelists, actors or scientists if all potential aspirants to these careers took action based on a normatively justifiable probability of success. We might also have few new products, new medical procedures, new political movements or new scientific theories.

If it weren't for the benefits of the biases that generate stubbornness, then, we'd have little art, music, business or science - and we'd probably be living under a Nazi dictatorship.

We should not, then, criticize Osborne for being stubborn. Stubbornness can be a virtue. The problem instead is that he's simply wrong.

February 23, 2013

Policy failure, no economic damage

Sometimes, even abject policy failure doesn't make much material difference. This is the paradox of the UK government's loss of its AAA credit rating.

Economically speaking, this won't make much difference. As I wrote recently:

Markets are relaxed about the possibility that rating agencies might soon cut the government's credit rating from its present AAA grade. Such a prospect, says Sam Hill at RBC Capital Markets, "is priced in".

And Reuters reports:

Charles Diebel, a fixed income strategist at Lloyds, was sanguine about the impact of the downgrade on gilts, as U.S. and French debt was not badly affected when these countries lost their triple-A ratings.

"This has been speculated as inevitable and is most likely largely in the market. I would expect only very limited damage to the gilt curve and to sterling. Historically, losing your AAA is actually a bond bullish event," he said.

There's a simple reason for this. Ratings agencies don't usually tell investors anything they don't know already, and on the odd occasions when they do, they are often wrong. There's no new news about the public finances in Moody's statement.

The truth is, of course, that the government's creditworthiness is impeccable, simply because - even if the worst comes to the worst - the Bank of England can print as much money as is necessary to buy gilts. There is, therefore, no chance of the government ever having to default on its obligations to borrowers, unless it chooses to do so.

However, even if you think all the above is wrong and that credit ratings matter, they still don't matter much.

The best measure of what an AAA rating is worth comes from the US municipal bond market. Here, a one-notch rating cut adds 0.23 percentage points to five-year yields.

But this is puny. If we use the Bank of England's estimate (pdf) of the effect of the first £200bn of QE as a guide - it estimates that this reduced gilt yields by a percentage point - an extra £50bn of QE would offset the impact of the downgrade.

However you look at it, then, the economic effect of Moody's move is insignificant.

Instead, it matters only for party political purposes. "We will maintain Britain's AAA credit rating" said Osborne in his Mais lecture in February 2010. "We will safeguard Britain’s credit rating" promised the Tory manifesto (pdf). In this sense, Moody's move represents a failure of policy.

Sometimes, though, policies can be so silly that their failure doesn't much matter.

February 22, 2013

Encouraging irrationality

Most people agree that rational behaviour is a good thing, which should be encouraged through education or, if necessary, nudging. However, a new paper by Daniel Pi challenges this. In some contexts, he says, we'd benefit if we were less rational.

Take crime. The rational person weighs the benefit of mugging someone - the financial reward and the buzz of the violence netted off against the feeling of guilt afterwards - against the cost; the probability of being caught multiplied by the punishment.

But we don't really want people to think so rationally because it would lead them to actually mug someone occasionally. It would be better if they had the heuristic "don't mug people." Such a heuristic is, however, irrational in the narrow economistic sense, as it would cause people to reject occasionally profitable actions.

The best policy, then, says Mr Pi, is not to debias people, as nudgeists would like, but to bias them - to encourage the spread of the "don't commit crime" heuristic which, whilst irrational for (some) individuals is socially beneficial.

There's an analogy here with the theory of the second best (pdf). This says that if there is a market failure, welfare can sometimes be increased by moving further away from optimality rather than by moving towards it.In similar fashion, moving away from rationality might enhance aggregate welfare.

This issue might be acute in the field of corporate tax. Companies apply economic rationality in considering how to minimize their taxes, but many people think that such behaviour is detrimental to aggregate welfare. If you agree with such folk - which is another issue - the question then arises of how to increase tax morale, to inculcate a "pay fair tax" heuristic. There are (at least) three possibilities:

- Customer boycotts. These operate on the rational cost-benefit calculus of whether to pay tax, but also help foster the "pay tax heuristic" by encouraging a "doing well by doing good" ethic.

- Arrest and punish high-profile tax-dodgers. This can deter crime through the availability effect; people over-estimate the probability of events they can easily see and recall.

- Introduce an element of arbitrariness into the probability of detection and punishment. If people can't calculate the probability of getting caught and punished, they'll decide to err on the safe side.

These last two can be applied to crime generally.But they run into the objection that it's normally desireable that the law be applied equally and predictably. This, though, just repackages the paradox we began with. Part of the case for having clear and consistent laws is that they permit individuals to make rational plans. If, however, those rational plans are harmful to others, then perhaps rationality is not to be encouraged.

February 21, 2013

Jobless danger for wages

The MSM reports that yesterday's figures show that unemployment fell to just over 2.5 million. This greatly understates the true level of joblessness.

The figures also show that there are 2.32 million who are economically inactive but who would like a job. Adding these to the official unemployment count gives us a total of over 4.8 million who are not working but would like to. That's 12% of the working age population.

One common objection to this calculation is that the inactive's claim that they would like to work is just an idle preference.Such people haven't actively sought work in the last four weeks and/or are unavailable to start in the next two; if they were, they'd be measured as unemployed.

However, other figures yesterday - on labour market flows - show that this objection is false. They show that, in Q4, 423,000 "inactive" people became employed. That's equivalent to 18.1% of all the inactive who'd like a job. By comparison, 595,000 moved from unemployment to work - 23.7% of all the unemployed.What's more, of the 871,000 who lost their jobs in Q4, more moved into inactivity than unemployment (453,000 vs 418,000).

These numbers tell us that, for practical purposes, the distinction between "unemployed" and "inactive" is blurred. In practice, there's not much difference between being "inactive" and being unemployed.

You might wonder how it can be that so many people can find work if they are not actively seeking it. I suspect much hinges on the vagueness of "actively". Consider two people. One distributes his CVs to firms speculatively. The other asks family and friends to listen out for vacancies. You might think the former is "actively seeking" work whilst the latter isn't. But given the importance of social networks for getting jobs, the latter could have as good a chance of finding work as the former.

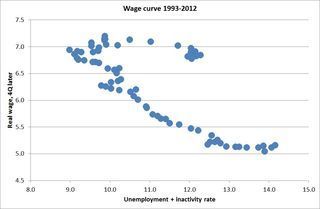

My point here is not just that the official figures greatly understate employment. There's worse, shown in my chart.It plots the unemployment plus inactivity rate since 1993 (when data began) against real wages four quarters later*.It's a variant of the wage curve (pdf).

This shows that, between 1993Q2 and 2007Q4, there was a humungous negative correlation between the two - of minus 0.94. A greater excess supply of labour led to lower real wages, and less excess supply to higher ones. That's Econ 101.

However, since the recession began, the wage curve seems to have shifted rightwards. The excess supply of labour has not depressed real wages as much as you'd expect. In fact, if the 1993-2007 relationship had continued to hold, real wages would now be almost 20% lower than they actually are.

In this sense, the puzzle is not: why have real wages been squeezed? It's: why have they not fallen much more?

And herein lies a danger. If the wage curve does return to its 1993-2007 pattern, real wages could fall a lot. I don't know how likely this is. But you could interpret the fact that real wages have fallen recently at the same time as the jobless rate has also fallen as a sign that this risk might be materializing.

Perhaps, then, the downward pressures on real wages are much greater than generally thought.

* I define real wages as total compensation of employees, divided by the number of employees, deflated by the CPI.

February 20, 2013

Happiness, work & productivity

"A happy worker is a productive worker". This might seem like a vomitorious cliche, but some experiments at the University of Warwick suggest that it's true.

Economists paid people to solve some tedious maths problems. They found that subjects who were shown a short comedy film beforehand solved significantly more problems than those shown a neutral film. And subjects who had suffered a recent bereavement solved fewer. "Happiness makes people more productive" they conclude.

This suggests that firms wanting to raise productivity should want their workers to be happy.

But this is not the case. Zoe Williams describes how big employers treat their low-paid workers with contempt and suspicion. And a great new paper by Alex Bryson and George MacKerron shows how even well-paid workers are unhappy whilst they're working. Using mappiness to measure people's momentary happiness, they found that work was associated with lower happiness than all but one of 40 various activities - the exception is being ill in bad. Work makes us even unhappier than queuing or commuting, and is as bad for our happiness as drinking or pursuing hobbies is good*.

This is not true merely for low-paid work. If anything, the opposite; lower paid workers are less unhappy at work, perhaps because they realize they need the money more, or perhaps because they get less happiness from leisure**.

This poses the question: if happiness raises productivity, why don't employers try harder to prevent people being miserable at work? There are, at least, three competing possibilities:

1. It's not technically feasible. High productivity requires a detailed division of labour, but this naturally creates jobs which people find frustrating. As Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan point out in The Org, some companies' attempts to foster teamwork and camaraderie just fail.

2.Employers fail to see the benefits of obliquity. Making workers happy is an oblique way of increasing efficiency. Monitoring them closely to ensure they meet targets is the direct way. And bosses have a cognitive bias - a form of the representativeness heuristic - in favour of direct methods.

3. Employers aren't interested in productivity, but in profits.And experimental evidence corroborates what we know - that many employers prefer methods which are profitable but inefficient in aggregate to ones which are efficient but less profitable.

* Sex makes people happiest - even, apparently, if they do it whilst using their phones.

** This evidence is consistent with the well-known fact that the unemployed are, on average, less happy than those in work, as workers are happier when they are not working.

February 19, 2013

Politics as stepping-stone

James Purnell, former Work & Pensions Secretary is going to become the BBC's "director of strategy and digital" on a a salary of £295,000 - and no doubt worth every penny. This suggests we should change the way we think of Westminster politics.

Purnell is continuing a trend for quite young people to leave politics for more lucrative work: Ruth Kelly, John Hutton, David Miliband (perhaps temporarily) and even Tony Blair. Whereas politics used to be something one undertook after gaining experience in other careers, it is now a stepping stone, something youngish people do as a means to bigger money*.

Such a path is understandable. Politics offers someone of average-to-decent ability a chance to manage multi-billion pound budgets at a younger age than they'd often get in ordinary business. Sure, they might not accomplish much whilst they are in government. But as Marko Tervio has shown, employers often prefer the mediocrity with a track record to the potential star without, so "Secretary of State for Work & Pensions" looks better on the CV than a string of competently-done junior management jobs.

Once we we regard politics as a means whereby 30- and 40-somethings gain experience before going onto better things, then several things follow:

1. We should be more forgiving of mistakes in both policy and execution. These guys are only learning their craft, so mistakes are inevitable. Politics is youth team football, not the Premier League. Sure, they're making mistakes with our money, but hey-ho.

2.Political reporting - in the sense of who's up, who's down - is not important, any more than is the matter of who becomes deputy assistant marketing director at Amalgamated Aerosoles. Of course, policy matters, as do questions of values about how we are governed. But individual ministers don't matter; they're just passing through.

3. We should expect politics to be biased towards crony capitalism and managerialist ideology not because these are goods way of running the country, but because they are ways in which ministers increase their chances of getting lucrative work later.

* Actually, the distinction isn't so sharp. It was quite common in the 50s for men to become MPs in their early 30s, and ministers have often taken directorships after leaving politics - although many of these were sinecures to subsidize retirement rather than, as now, a career advancement.

February 18, 2013

Leftist Tories?

Have the Tories gone soft? At the weekend, George Osborne spoke about taking steps to reduce corporate tax dodging. And today (in the Times £) Tim Montgomerie supports a mansion tax.

What's going on here might be more than just an effort to "detoxify the brand." It's what we saw in Disraeli's "one nation" Toryism, Bismarck's creation of the welfare state and in the Tories' acceptance in the 1950s of most of the welfare state built by the 1945-51 government - an attempt to buy off discontent.

Yes, the Tories are the party of the rich. But it is not always in the collective interests of the rich to get immediately even richer.This aim must be balanced against the aim of ensuring the social stability which allows the rich to stay rich in future. As James O'Connor wrote:

The capitalistic state must try to fulfill two basic and often contradictory functions - accumulation and legitimization...This means that the state must try to create or maintain the conditions in which profitable capital accumulation is possible. However, the state also must try to maintain or create the conditions for social harmony. (The Fiscal Crisis of the State, p6)

Osborne and Montgomerie fear that a backlash against inequality might lead to support for harsher redistributive policies which hinder capitalist accumulation. So they want to enact such policies on their own, milder terms. It's a form of vaccination: introducing a small amount of the disease of redistribution can protect the capitalist organism against the bigger disease of even greater equality.

Insofar as the Tories have been successful down the decades, it's because they've been able to balance accumulation and legitimization; Thatcher stressed the former, Disraeli the latter, but they are two legs of the same beast.

This raises two questions. First, how strong are the material pressures on the Tories to adopt a more egalitarian stance? I'm in two minds here. On the one hand, working class power is sufficiently weak that it can be ignored, which means there's little need to "bribe the working classes", in Bismarck's phrase. But on the other hand, the social norm against corporate tax-dodging is strong, and the hope that enriching companies would encourage investment and growth seems to have been dashed - both of which point to the need for more legitimization policies.

Secondly, if redistributive policies can be adopted by the "right" (eg Disraeli, Bismarck), and if they can be shunned by the "left" under pressure from capital (eg New Labour), could it be that we over-rate the importance of the colour of the government, and under-rate that of the social norms and class power which constrain governments? At least some economic research (pdf) suggests the answer might be: yes.

February 17, 2013

Power, skill & wealth

Does wealth flow to skill, invention and service to others - as neoclassical economists maintain - or is it instead a rent extracted by the powerful (pdf), as various heterodox economists claim?

In many cases, it's hard to say because the two are very similar. Skill is scarce and scarcity is a source of power, so returns to skill and returns to power are often the same thing. For example, if you want an iPod as distinct from other MP3 players, Apple has power to charge a premium price. But this power lies in an ability to design a desireable product.So, are Apple's profits a return to invention, or to power?

Luckily, we have a case to adjudicate between the two hypotheses.Trevor Baylis, inventor of the wind-up radio and undoubtedly a great contributor to human well-being, is potless:

Due to the quirks of patent law, the company he went into business with to manufacture his radios were able to tweak his original design, which used a spring to generate power, so that it charged a battery instead. This caused him to lose control over the product.

This vindicates the heterodox economists against the neoclassicals.

You might object that Baylis was naive. Maybe. But an economy in which people distrust each other will be a poorer one, and one in which everyone bones up on the details of the law is one in which they have less time to devote to their true specialism, with the result that we have less division of labour and lower productivity.

Of course, drawing strong inferences from Mr Baylis's case alone would be committing the journalist's fallacy. But his case is not wholly atypical.William Nordhaus has estimated that "only a miniscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances over the 1948-2001 period was captured by producers". This suggests Trevor Baylis is more typical than Bill Gates.

And this is not the only way in which wealth flows to power rather than ability, at least as widely understood:

- Why did bankers get a bail-out when HMV staff didn't? It's because bankers had the power to persuade the state that hand-outs were necessary to stave off disaster, whereas HMV workers didn't.

- Moshe Adler has shown (pdf) that relatively ordinary people can get superstar-style incomes if they go viral and get widely talked about: think of Dan Brown, Kim Kardashian, and linkbait journalists. The power (or luck) to get yourself talked about matters more than talent.

- CEOs' high pay is the result of power - an ideological structure which presumes that the ability to manage companies is a scare talent requiring huge "compensation", and a power to extract rents.

- Where skill can only be revealed by working with expensive resources - such as film actors or CEOs - employers will often prefer the known mediocrity to able people who lack the power to prove their talent.

- in crony capitalism (the only capitalism we have), profits go to firms that can use their connections to win juicy state contracts or protection, not necesarily to the most efficient.

We have enough cases here to show that power matters more than neoclassical economics would have us believe. In many cases, the idea that financial success is a reward for ability and service to others is just a fairy tale.

February 16, 2013

Narcissism & power-blindness

Alex Massie's attack on the narcissistic left has been quite widely praised. But I'm in two minds about it.

To some extent, he has a point. As Phil says, there is an element in the left of "individuated identity politics...that can justify petty, spiteful, bellicose, moralising behaviour toward groups one doesn't like": he cites some atheists, but we could add that recent row about transsexuals.

My gripe with this type of politics is that the focus on individuals distracts us from power relations; it's an application of the fundamental attribution error. For example, capitalists dodge taxes and exploit workers not so much because they are greedy and immoral people but because doing so is the logic of capital; capitalists are "capital personified."

Similarly, the rich are rich not (just) because they work hard or are talented, but because they have the power to extract money from others*. And the unemployed are unemployed not (just) because they are lazy but because "unemployment is an integral part of the 'normal' capitalist system."

This point also applies to the matter in hand. The complaint from Laurie and Owen, among others, that the two million antiwar protestors were ignored or "betrayed" under-emphasizes the fact that those two million lacked power. This might have been legitimate - they were in fact out-numbered at the time. Or it might be more questionable; support for the war might have been based in part upon a lie and as Phil acutely notes, MPs' attitude to public opinion varies peculiarly.

Let's concede, for the sake of argument, that the protestors had morality and reason on their side. So what? Morality and reason matter only to the extent that they are sources of power.

In this way, the narcissism of degraded leftist identity politics serves an anti-leftist function, of blinding us to pervasive inequality. The non-Marxist left is as much a product of capitalist ideology as anyone else.

So far, I sympathize with Alex - albeit for reasons he might not like. I part with him for three reasons:

1.Laurie is groping towards a recognition that it is power structures that matter more than individuals' qualities: "We have to make sure that we are listened to – and we’re still working out how to do that."

2. It's not just the left that's narcissistic. We live in a narcissistic age, and the narcissism of the powerful has much nastier effects than that of the left.

3.Complaining that MSM columnists such as Owen or Laurie are narcissists is rather like noting that basketball players are tall. A degree of narcissism is necessary for success in their career, as it is in many others. As someone said, "It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness."

* The distinction isn't so sharp, as "talent" can be a way of achieving power.

February 15, 2013

Freedom: a matter of life & death

Stephen Dorrell, chairman of the Health Select Committee, wants to stop the NHS enforcing "gagging clauses" on former employees. He's more correct than he knows. The issue here is not just one of freedom, but of life and death.

I say this because of something Joseph Hallinan says in Why We Make Mistakes. He points out that whilst the accident rate for aiplanes has fallen sharply since the 1930s, the rate of medical misdiagnosis has declined more slowly (pdf), so that - in the US - well over 30,000 people a year die as a result. A big reason for this difference, says Mr Hallinan, is that:

ORs are typically hierarchical places, with the surgeon on top; cockpits are not...When it comes to pointing out potential errors, everyone [in a flight crew] is considered equal (p194).

Hierarchy inhibits feedback: nurses don't challenge doctors; junior doctors don't challenge senior ones, nobody challenges managers, and so on.

But feedback is essential for improvement.If a musician couldn't hear what he was playing, or a golfer couldn't see where his shots went, do you think either would get better? This point is emphasized by Matthew Syed in Bounce. Feedback, he says, is "the rocket fuel that propels the acquisition of knowledge". Good feedback "is the reason why mankind has progressed." Geoff Colvin agrees:

We've examined at length the importance of frequent, rapid, accurate feedback for improving performance. Most organizations are terrible at providing honest feedback...Tet nothing stands in the way of frequent, candid feedback except habit and corporate culture. (Talent is Over-rated, p131-2)

It's in this context that "gagging orders" are - literally - fatal. They limit feedback. Sure, the feedback might be noisy - an outgoing employee might have questionable motives, but a noisy signal is (probably) better than none. Whistleblowers are essential to progress.

Of course, nobody thinks that removing gagging orders is sufficient. Matthew Green says: "To implement any kind of change in the NHS means challenging a whole mass of entrenched hierarchies". And Paul advocates weekly meetings between management and staff. They are right. Improvements come from feedback, which requires openness and a sufficiently egalitarian atmosphere that encourages junior staff to speak honestly.

Why, then, could anyone possibly oppose this? Simple. Feedback challenges the self-image of the powerful; it tells doctors that they are not godlike experts, and managers that they are not running immaculate organizations. Alex Massie decries the narcissism of the left. But that is merely irritating. The narcissism of the powerful can be fatal.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers