Chris Dillow's Blog, page 160

January 13, 2013

Suzanne Moore & the nature of politics

My immediate reaction to that piece by Suzanne Moore and the reaction to it was the depressing confirmation that I just don't understand women. On reflection, though, what's also causing me consternation is a difference in the conception of what politics is, or should be, about.

From one perspective, being respectful to transsexuals is a matter of basic courtesy, not a political issue.

Herein, though, lie two different conceptions of politics, both of which rest on different ways of interpreting the slogan "the personal is political."

In one conception, all aspects of personal behaviour become political. Rudeness to transsexuals thus automatically becomes a political matter, just as does behaviour such as how much we save and what we eat.

In another conception, though, the slogan draws our attention to the fact that personal behaviour is shaped by political forces, by power relations.

There are (at least) two aspects here which Marxism draws our attention to.

First, the division of labour creates fixed social roles which do not necessarily fit our humanity well. Communism, by contrast, would overcome this alienation:

As soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic. (The German Ideology)

Though Marx is talking about economic roles, here, his point generalizes easily to gender roles - especially as social science has shown that gender identities are partly socially constructed.

From this perspective, hostility to transsexuals is politically reactionary, in as much as it represents an internalization of the alienation imposed upon us by pre-communist social structures, and a failure to embrace the communist ideal of more flexible social roles.

Secondly, the ideology created by inequality - and exacerbated by capitalist crisis - leads people to behave meanly to others. The just world illusion leads to a blaming the victim effect the out-group homogeneity bias facilitates "divide and rule" tactics by the ruling class, and so on. In this sense, nastiness towards transsexuals, like hostility to the disabled or immigrants, is a product of capitalist ideology.

It would, of course, be idle utopianism to believe that radical social change would eliminate all nastiness. My point is just that politics (for Marxists such as me at least) is about power relations and the basic structure of society. What's depressing about "Mooregate" is that this point is easily forgotten.

January 12, 2013

Don't pay MPs more

The news that MPs think they deserve a £20,000pa pay rise is neither surprising nor relevant. Not surprising, because we all think we're underpaid. And not relevant, because pay does not and should not depend upon desert. Instead, the question is: if we paid MPs more, would we get better governance? I'm not sure.

There are three ways in which higher pay can improve labour supply. And whilst they might apply to some politicians sometimes, I'm not sure they apply to MPs now.

1. "Higher pay would attract better candidates." Richard Murphy says that doctors, headteachers and other professionals have to take a big pay cut if they want to become an MP, and this deters talented people.

There are three problems with this. First, as Paul says, the job of being an MP doesn't require huge skill. You need to be a genius to obey the whips' orders. Secondly, do we really want good doctors and headteachers leaving their jobs to become humdrum backbenchers? Can't they do more good in their current jobs? Thirdly, there's a danger that paying MPs more will crowd out the intrinsic motive of "public service." Do we really want MPs who are only motivated by cold hard cash?

2. "Higher pay would make MPs work harder, as the pain of losing their job would be greater."

But there are few cases of MPs not trying as hard as possible to hold their seats now - not least because of non-monetary motives to be an MP. The exceptions to this hardly support the case for higher MPs pay; would political life really be better if Louise Mensch had remained MP for Corby? And even if MPs did work harder, it's not clear this would be a good thing. I suspect that, in recent years, we've needed less legislative activism and more scrutiny of legislation. Would higher pay really have elicited this?

3. "Higher pay generates good will, and so buys off fraudulent behaviour."

Generally speaking, this is an under-rated reason for high pay. But I'm not sure it's relevant now. I suspect that British MPs are, by global standards, relatively honest already; fiddling a few grand in housing expenses is low-level stuff. And cross-country comparisons suggest little negative correlation between politicians' pay and honesty; MPs are paid more (pdf) in Ireland and Italy than in the Nordic countries, for example.

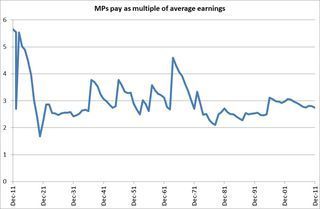

So much for my hypotheses. What of the historical evidence? My chart shows MPs pay (pdf) relative to average earnings. This shows that their present pay - at 2.7x average earnings - is in line with the historic average. Except for a brief period when MPs' pay was introduced in 1911, the best time financially to be an MP was the 1960s. But were we really well-governed then? Given that MPs included Maudling, Stonehouse and Driberg then, it's not at all obvious.

January 10, 2013

Irrationality & the benefits debate

Alex Andreou says the debate about benefit cuts has been so bad that it represents the "End of Reason." Many good judges agree. But what is the source of the irrationality?

Let's start from Hopi's point that the distinction between shirkers and strivers is a "false divide." He's right. Official figures show that, in Q3, 871,000 people lost their jobs. That's 3% of all employees. This is not so much thanks to the recession as to the fact that even in normal times, job destruction is high; over 50,000 jobs were destroyed each week between 1997 and 2005.

This means there's a significant risk that "strivers" will become benefit claimants themselves. So why are so many hostile to claimants? People who pay home contents insurance don't regard insurance claimants as scroungers (though some are!).And if, say, Aviva were to announce that it will cut its payouts to insurance claimants, its customers would be aggrieved. So what's different about the insurance system that is the welfare state?

In theory, the hostility could be rational. If people are risk-tolerant, they might judge that the adverse effects (in good economic times) of unemployment benefits on work incentives outweigh the gains from better risk-pooling.

But this runs into several problems. High demand for poor-value insurance products such as PPI and extended warranties, and low stock market participation, suggest that people aren't risk-tolerant and so should favour higher unemployment protection. The benefit cuts apply to tax credits as well as out-of-work benefits and so have ambiguous effects upon work incentives. And OECD data show that the UK's out-of-work - even including child and housing benefit - are quite mean by international standards, suggesting that work incentives here are already quite sharp.

This leaves us with other possibilities. One is that people have a powerful instinctive norm of reciprocity, and so want to punish "scroungers" who violate that norm, even if doing so hurts themselves. Perhaps, then, we tolerate low welfare benefits - even though they offer us less protection - as a price worth paying to enforce this social norm.

But this runs into the problem that, at a time of mass unemployment, the idea that people should look for work is actually harmful to "strivers". In this context, the norm of reciprocity is an atavistic anachronism.

Perhaps, though, something even less rational is happening. Maybe hostility to benefit claimants is founded upon a mix of ignorance about the true levels of benefits, and cognitive biases, such as the optimism and self-serving biases, which lead people to under-estimate their chance of losing their job, and so undervalue the worth of out-of-work benefits.

Perhaps, then, Alex is right, and support for benefit cuts is irrational. What he doesn't say, though, is that this raises (more) doubts about the value of democracy. From the point of view of winning votes, a reasonable (though in my view mistaken) concern to improve work incentives has as much weight as sheer ignorance and irrationality.

It's sometimes said that "democracy is two wolves and a sheep deciding what to have for dinner." What we have here, though, is sheep thinking they are wolves.

January 9, 2013

In praise of cowardice

Tim Harford's new year's resolution is to be less loss-averse. Oliver Burkemann bemoans our irrational security-obsessed culture. And Luke Johnson writes that "too much risk aversion means a life of disappointment and lost chances." All this aversion to risk aversion makes me wonder: isn't there something to be said for cowardice?

History is often told as a story of feats of derring-do by great men. But society is shaped by the deeds of everyone, not just a few. Which suggests that cowardice might have played a role. Here are five effects, three positive, and two negative:

1.It reduced wars and theft; as Judge Peter Bowers said, it takes courage to be a thief. In this sense, cowardice has contributed to more secure property rights, which in turn has encouraged investment and economic growth. As Tim Besley shows (pdf), peace dividends can be large. It's no accident that the UK's industrial revolution began after a decline in violence, or that societies which value martial virtues - from hunter-gatherers through medieval Japan to North Korea - tend to stay poor.

2.The (irrational) fear of the sack can raise productivity and depress wage demands, thus reducing the Nairu. One unjustly neglected reason for full employment in the 50s and 60s was that workers remembered the depression of the 1930s and so were more quiescent than their objective bargaining position would justify. But as this cowardice declined - as workers who remembered the 30s retired and were replaced by braver younger ones - so full employment and low inflation proved to be unsustainable.

3. Cowardice reduces population growth; faint heart never won fair lady or - let's be blunt - raped her. And there's reasonable (pdf) evidence that, at least in poor societies, lower population growth (pdf) is conducive to faster per capita GDP growth.

So much for the positive effects of cowardice. Here are two adverse ones:

1.As Luke says, it reduces entrepreneurship and self-employment. Now, this is not a wholly bad thing. As Rick has pointed out, self-employment is often associated with weak economies, in part because entrepreneurs are often under- or poorly-employed. However, this is one of those areas where tails matter; a small minority of entrepreneurs can transform industries. The more cowardice there is, the fewer of these there'll be.

2.Cowardice reduces immigration. It takes guts to up sticks and move to an unfamiliar country. If everyone had been a coward, the US would not have been settled by Europeans - and unlike many lefties, I think the US is (net) a Good Thing. And migration can benefit both host and supplier countries.

Quantifying the net effect of all this is, I suspect, impossible: cowardice is about what didn't happen rather than what did, and it's very hard to distinguish between rational risk-aversion and irrational aversion. But I suspect that the role cowardice has played in history - and still plays today - isn't wholly bad.

January 8, 2013

David Bowie & consumption capital

David Bowie's new single raises an important economic point - that perhaps young people who aren't saving for their retirement are behaving more rationally than the so-called experts claim.

For many of us, I suspect, this release corroborates David Hepworth's point that we don't love new music by our favourite artists as much as we loved their older work, even if the two are indistinguishable to a neutral listener.

What's going on here is partly a framing effect; the pre-Tin Machine era Bowie was so brilliant (including the Deram years) that anything short of one of the greatest pop singles of all time would be disappointing.

But there's something else going on. It lies in the concept of consumption capital (pdf), described by Gary Becker and George Stigler.

When we bought and listened to Bowie records in the 70s and 80s we accumulated a stock of consumption capital. And the utility we derive from this is so great that a new addition to it naturally has low marginal utility.

In other words, what we think of as consumption is, in many cases, a form of saving - something that gives us utility in future years.Just as saving builds financial capital which we can draw on in future, so spending builds up a stock of satisfaction which we can draw upon in the future.

Does anyone really think the money they spent on Hunky Dory would have been better invested in the stock market? (If you do, leave now; you're not the sort of reader I want.)

And herein lies a reason why it might be rational for young people not to save in the conventional sense of the word. In spending money, they are building consumption capital.

Now, I appreciate that youngsters today don't believe in spending money on records. But there are many types of consumption capital.Spending on holidays and nights out accumulates a stock of happy memories. Spending on guitars and music lessons gives us a stock of leisure skills which give us future satisfaction. And so on.

Of course, not all spending is a building up of useful capital. Some of it, such as an addiction to heroin or fine wine is the acquisition of the liability of expensive tastes. But my point is that high spending and low (financial) saving does not necessarily mean that people aren't preparing for the future. Our well-being today isn't increased merely by our past saving, but sometimes by our past spending.

When the financial "services" industry claims we are saving too little, it is expressing not merely crude vested interests, but perhaps bad economics too.

January 6, 2013

Obesity & ideology

It's tempting to regard Andy Burnham's suggestion that the government ban Frosties - and Sugar Puffs! - as yet another example of New Labour's statism. I fear this might be too glib. If Labour were consistently statist, it would occasionally blunder into an intelligent use of the state, such as in its role as employer of last resort. But it thinks - wrongly - that guaranteeing jobs is something that can be done by the private sector. This poses the question: why is Labour statist in some regards, but not in others?

The answer, I suspect, lies in the party's managerialist ideology. I mean this in two senses.

First, there's a lack of faith in the decision-making capacities of ordinary folk. Sugary cereals must be banned because people can't choose the best diet for themselves or their kids. The unemployed must be forced to take jobs because they cannot be trusted to make proper work choices. By contrast, the possibility that corporate managers will make incompetent decisions (for example in deciding not to invest or hire) doesn't get the attention it should.

Secondly, there's also an asymmetric attitude to perfectibility. In considering personal behaviour, Burnham fails to heed Smith's advice that there is a great deal of ruin in a nation, and seems to think that government action can make us all paragons. Such optimism, however, does not extent to the economy. Mass unemployment and inequality are "natural" and governments - whilst perhaps able to ameliorate these - cannot eliminate them. Whilst capitalism is taken for granted and is unchallengeable, obesity is not.

What we're seeing in Burnham's remarks, then, is ideology at work. And the thing is, I suspect he's not aware of this.

January 4, 2013

Jobs Guarantees, good and bad

You can rely on the Labour party to live down to its reputation as a party of capitalism. Its "compulsory jobs guarantee" does so in two ways.

First, the fact that it will be compulsory for the long-term unemployed to take up the jobs panders to a mistaken "divide and rule" rhetoric that distinguishes between skivers and strivers. As Neil says, the party is - yet again - "running scared of the Daily Mail".

Secondly, the policy will, as Liam Byrne says, "provide subsidy" to private sector employers to hire the long-term unemployed.Labour will, in effect, give taxpayers' money to Tesco so it can employ more shelf-stackers.

And herein lies the economic problem with the scheme. At the margin, employers will prefer to hire a subsidized long-term unemployed person rather than an unsubsidized short-term unemployed one. In this sense, Labour's plan improves job prospects for the long-term unemployed, at the expense of the short-term unemployed, and has a deadweight cost of paying companies to do what they would have done anyway*.

Labour's plan thus falls far short of more sensible "employer of last resort"-style policies to combat unemployment. It accepts capitalism as it is, and fails to confront the fact that capitalism is unable to provide work for all.

All that said, there is something to be said for the plan. It starts from the sad fact that public opinion about welfare is ill-informed and ignorant. Faced with this, a sensible party should campaign in lies and govern in truth. It should wibble, as Byrne does, about people needing to be "working or training, not claiming" simply because this is the easiest way to get votes from bigots. In office, when the scheme is up and running, the compulsory element can be quietly dropped, on the grounds that it is costly to administer and enforce.

And then, when the evidence shows that subsidized jobs are of poor quality, and are displacing the shorter-term unemployed, the party can switch from subsidizing the private sector to creating new jobs through a programme of public works, in the way a proper job guarantee scheme would.

In this sense, if Labour's plan has any merit, it is as the thin end of a wedge.

* Granted, there might be an income effect; employers getting the subsidy might feel able to hire more people generally, but this effect might not be large.

January 3, 2013

Agency & reciprocity in Corrie

It's a commonplace - at least to me - that you can learn a lot about economics from watching TV as long as you avoid news and current affairs programmes. This is true of Corrie, where Rob's efforts to defraud Carla - or, as I think of her, the future Mrs Dillow - have highlighted some important principles.

One is the danger of principal-agent failure. When Rob heard that Carla wanted to sell Underworld, he fiddled the accounts to give the impression that the business was of little value, thus making it possible for him to buy it.

Such behaviour is widespread. In a famous paper, Simon Johnson and colleagues showed how "tunnelling" - the transfer of corporate assets from small shareholders to controlling ones - can be "substantial." And as Eric Falkenstein has said, a big danger with banks having complex portfolios is that traders might sell them cheaply to others, to build up favours. Money flows from the powerless and uninformed to the powerful and informed.

However, Rob (whos name represents another victory for nominative determinism) did not set out to defraud Carla. For months, he worked well for her. This highlights a principle discussed by Robert Cialdini - the power of reciprocity. Initially, Rob was grateful to Carla for giving him the job, and he repaid her by getting new customers. It was only when he saw this reciprocity break down that he became dishonest.

Herein lies a big reason why people who have power over corporate assets - such as bosses or bank traders - are well-paid. Paying someone millions of pounds isn't necessary to elicit great effort. But it is necessary to buy the goodwill that stops them thieving.

Thirdly, consider Rob's response when he was caught (8'30" in). He says he "was the only person interested in keeping this place going, ultimately saving everybody's job" and that he was "a loyal lieutenant who kept this place afloat." This is not false, but it's an example of what Dan Ariely calls "cognitive flexibility". We tell ourselves stories, he says, which justify even obvious wrongdoing:

Our sense of our own morality is connected to the amount of cheating we fell comfortable with. Essentially, we cheat up to the level that allows us to retain our self-image as reasonably honest individuals. (The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty, p23)

In these ways, Rob is an exemplar of the new homo economicus.

January 2, 2013

Politicians' existential crisis

"Kicking the can down the road" quickly became a cliche to describe European policy-makers' inadequate response to the debt crisis. I suspect it will just as quickly become the cliched description of US fiscal policy. As Ed Dolan says, the deal to avert the fiscal cliff "does nothing" but postpone many important decisions, and Jeff Sachs in the Times (£) says: "US incoherence and unpredictability have a long way to run."

This raises a more profound question than generally realized: what exactly is the economic function of politicians?

Let's put the US debacle into perspective. From the 1970s onwards, it became the conventional wisdom in the west that a big job of government was to provide a stable framework so that businesses could stop fretting about at least some sources of uncertainty; this view united both Milton Friedman's famous AEA presidential lecture (pdf) and Ed Balls' thinking (pdf) about New Labour's macroeconomic policy. Of course, the crisis has taught us that this is not sufficient to achieve acceptable economic growth, but it might be necessary. As Nick Bloom and colleagues have shown, policy uncertainty can have hugely adverse (pdf) effects upon investment and jobs.

And yet policy uncertainty is exactly what Congress - and we might add euro area "leaders" - are offering.

An analogy from Michael Oakeshott helps us see why this has happened.He wrote (pdf):

The image of the ruler is the umpire whose business is to administer the rules of the game, or the chairman who governs the debate according to known rules but does not himself participate in it.

But now, politicians are participants rather than umpire. They are playing for particular ideologies (or principles), be it small government in the US or the punishment of debtors in Europe.

The pursuit of these principles, however, is undermining the function of government as the provider of certainty. What we're seeing here is an example of Poulantzas's relative autonomy of the state - the state is acting against the interests of capital (and, indeed, labour!)*.

But this is not the only sense in which politicians are not doing the job economists think they should. Here in the UK, the government has been unable to solve a simple problem of market failure - in social care - even when there is good advice on how to do so. And it has been woefully ignorant of what, to an economist, provides a role for government - that fact that the pursuit of self-interest can sometimes lead to outcomes that are collectively sub-optimal.

Hence my question. If politicians not only don't provide policy certainty but actually tend to increase it, and if they can't solve problems of market failure and collective action, what is, or should be, their purpose? In this sense, the US's fiscal cliff is part of an existential crisis of politics.

* You could (perhaps) argue that in fact small government is good for growth in the long-run. But I doubt that many Republicans are motivated solely by cross-country growth regressions.

December 31, 2012

Inequality, & statistics

John Rentoul has been causing trouble. "The gap between rich and poor has not changed significantly for about 20 years" he says - which is "at variance with the accepted story of food banks and greedy bankers".

In one important sense, he's right. According to the ONS, the share of post-tax, post-benefit incomes of the top 20% rose from 37 to 45% between 1977 and 1990, but has not changed much since; it was 44% in 2010-11 (table 26 here). And the share of the bottom 20% fell from 9 to 6% between 1977 and 1990, but is now also 6%.

However, these data - and measures of Gini coefficients - are not incompatible with stories about food banks and greedy bankers, for three reasons:

1. The story of inequality in recent years is not mainly about the top fifth or tenth, but about the growing incomes of the super-rich. According to the world top incomes database, the share of pre-tax income going to the best-off 1% rose from 9.8% in 1990 to 13.9% in 2009.

2. Similarly, simple measures of inequality can disguise what's happening to the very worst off. A given Gini cofficient can be compatible with either quite acute poverty or not, depending upon what's happening elsewhere in the income distribution. There is no necessary inconsistency between a stable Gini coefficient and the spread of foodbanks - because as Paul points out, the poor are less resilient to wealth shocks than the rich. Popular measures of inequality such as Gini coefficients or 90/10 ratios do not suffice to answer the Rawlsian question, of whether we are maximizing the position of the worst off.

3. Measures of inequality don't tell us how the rich get rich. The Gini coefficient is indifferent between the income of a Russian oligarch and Warren Buffett, or between that of Lionel Messi and Fred Goodwin. But as Acemoglu and Robinson stress, it matters enormously for the health of an economy (and society) whether the rich owe their wealth to extraction or production. Those of us who are unhappy with the wealth of the rich worry about its origin, not just - or even mainly - its size.

It's good that John is drawing our attention to statistics. But let's remember what they do and do not measure.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers