Chris Dillow's Blog, page 164

November 16, 2012

On managerialist ideology

There's one response to the Newsnight fiasco which, though plausible, hasn't been much aired. It's along the following lines:

This - and the phone-hacking scandal - shows that journalism is a very responsible job and that errors can prove costly. The BBC is paying the price for years in which journalists generally have been deskilled and underpaid to the extent that the job is now fit only for egomaniacs, the semi-retired, trustafarians and second-raters. Lapses like these show the need for journalists to be better paid to attract, retain and motivate genuine talent.

You have not been deafened by this sort of talk. Instead, the standard response has been to call for a restructuring of the BBC or a reorganization of its management. Radio 4's Media Show devoted an hour to such talk, without the thought occuring to anyone that the solution to sloppy journalism is, well, better journalism.

This inability to see the bleedin' obvious doesn't happen naturally. Such blindness can only be the product of ideology. I mean this in two senses:

1.The claim that high pay is necessary to attract and motivate good workers is not merely an economic postulate. If it were, it could apply across the wage distribution. Instead, it functions as a defence of inequality - used to justify higher pay for the rich, rather than for any job. For grunt workers, wages are a cost to be minimized regardless of consequence.

2. What we're seeing here is what Jeffrey Nielsen calls "rank-based thinking". We now take managerialism so much for granted that we assume that the only people who can possibly be responsible for improving an organization must be managers. The possibility that better workers can drive performance just doesn't occur to us.

Now, you will - of course - reply here that a call for higher pay for journalists shouldn't be surprising coming from a journalist. Fair cop. Except for two things. First, what I've said here doesn't apply only to journalism, but to other jobs too. For example, one plausible response to the Stafford Hospital and Winterbourne View scandals is that they shows a need to attract and motivate talented and diligent nurses and care workers. But this was not the primary reaction. And secondly, why doesn't such scepticism extend to those managers and their agents (politicians) who think that the solution to everything lies with management?

November 15, 2012

Defending left-libertarianism

Daniel Shapiro has questions for left-libertarians. He suggests that an economy of worker-owned firms will degenerate into a hierarchical capitalist one:

It will be irrational for workers to concentrate their portfolio in their own firm, lest it go under. So they will want to sell some of their shares in their own firm and buy shares in other firms. Once that happens it is not hard to see how those who don’t work in the firm will come to own considerable shares of the firm...Those who will supply considerable capital will tend to want some way to monitor that their capital is being used in an efficient manner, which means some kind of say over how the firm is run...

We get the scenario of outsiders coming to have full ownership rights in the firms, and it’s not hard to see how this will lead fairly quickly to an economy which is dominated by capitalist firms.

He's right that it would be irrational for workers to put all their eggs in one basket, and that they'd like to have shares in other firms. But this needn't lead to hierarchical capitalism.

For one thing, Workers who own shares in other firms might well believe that the best protection of their interests is not voice but exit; if they fear firms will be poorly managed, or their interests neglected, they'll prefer to sell rather than insist upon control rights. This is the predominant way in which shareholders protect themselves today. Why should it be otherwise in a left-libertarian economy?

This is especially so because by the time people are smart enough to want a left-libertarian economy, they'll be smart enough to realize that hierarchical management is very often a poor safeguard of shareholders' interests, both because of its inefficiency* and because of the opportunities it gives to rent-seekers.

Daniel continues:

It may be a firm needs to reach a certain size in order to be efficient, and that too little hierarchy can impede efficiency.

Up to a point.Staffan Canback has estimated that diseconomies of scale usually set in at quite small scales of firm size. This is consistent with the actual size distribution of companies. In the UK, only 0.4% of businesses have more than 250 employees. Daniel's right that access to cheap equity capital can give firms an advantage if they are trying to grow. But this advantage is swiftly counter-acted by the diseconomies of scale - not to mention the fact that, very often, firms' growth strategies fail for other reasons.

Daniel then asks:

Firms which are financed largely by equity will, in a freed market, be those that maximize shareholder value, and how do we know that a substantial number of those firms won’t be hierarchical firms?

The key feature of a left-libertarian economy is that workers will have more choice where or whether to work; this is because there'll be (initially!) a large coop sector and a citizens' basic income which gives workers an outside option. This will put repressively hierarchical firms at a disadvantage. To attract workers to less pleasant working conditions, they'll have to either pay higher wages or employ mindless drones**. Either way, they have higher costs and lower productivity. Will these disadvantages offset other advantages hierarchy might have? Let competition decide!

Now, I don't say this to pretend to that a left-libertarian economy would be a utopia. No economy would be. And here's a problem. Could it be that opposition to such economies is motivated in part by the sort of status quo bias that causes us to prefer present evils over potential alternatives? Put it this way. Say we actually had some kind of egalitarian economy, and some argued for hierarchy. They'd then face the retort: "What? You want to give hundreds of millions of pounds to people like Chuck Prince or Fred Goodwin so they can destroy the economy. Are you bonkers?" Doesn't hierarchy look more absurd when viewed from the egalitarian perspective than egalitarianism does when viewd from the hierarchical one?

* Imagine most national economies where heavily centrally planned. How difficult would you find it to argue that central planning was inefficient? A similar problem afflicts the question of assessing the inefficiency of corporate hierarchy.

** Some people don't like working at John Lewis because, when everyone's your boss, it's harder to shirk.

November 14, 2012

If exploitation increases...

The Bank of England expects capitalists to increase their exploitation of workers in the next few months. It doesn't quite put things this way, but that's what it means when it says (pdf):

In the central projection, the recovery in productivity growth outstrips that in nominal wages for a period, meaning that growth in companies’ costs falls back. That alleviation of cost pressures allows company margins slowly to be rebuilt.

You might wonder what it means by "rebuilt". Surely, the fact that real wages have fallen in the last 12 months means capitalists have already profited at workers' expense. What about all those stories of profiteering utilities' companies and suchlike?

Stop wondering. In fact, those workers who have kept their jobs have done quite well at capitalists' expense.

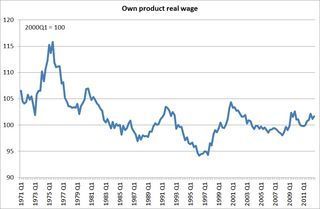

My chart shows the point. It shows the own product real wage. This is wages (defined as total compensation per hour) divided by the product of GDP per hour and the GDP deflator.

The idea here is that workers can gain at capitalists' expense if their wages rise relative to either prices or productivity; if our pay rises without us being more productive, we've won and capitalists have lost.

And this is just what's happened. Since 2008, productivity has fallen but real wages have fallen less. The OPRW has thus risen.

Real wages have fallen recently not because capitalists have become even more evil and exploitative, but because productivity has fallen. The economic pie has shrunk. Labour's share of it has held up well.

The Bank of England is predicting a reversal of this. This is not unusual. The OPRW fell during the recoveries of the early 80s and 90s, precisely because productivity rose faster than real wages.

Herein, though, lies a problem. Real wages (average earnings divided by CPI) are lower now than they were in 2005. If the Bank's forecasts are roughly right, they won't recover much soon. This could mean an entire decade or more of falling real incomes for many households. Will this be politically palatable if profits are seen to be rising? Might it not increase demands for tax cuts to restore living standards?

The political implications of the Bank's forecasts could be significant.

November 13, 2012

Youth, utility & discounting

Most people, I suspect, believe there's little connection between the music of Steely Dan and the economics of optimal consumption over time. But two things I've seen today suggests there is a link.

Simon points out an inconsistency between the Ramsey model and overlapping generations models.In the former, he says, people are impatient and discount their children’s utility as they do their own. But in OLG models, each generation is assumed to be selfish. Simon says:

If macroeconomists want to be consistent they need to do one of two things. If they want to continue to insist that a benevolent social planner should use the personal rate of time preference of the current generation to discount future generations, then they should also make the social planner ignore the utility of the unborn in OLG models...Alternatively, if they do not want to adopt this ethical position, they need to allow the rate at which the social planner discounts future generations (if any) to differ from individuals impatience in the Ramsey set-up.

I prefer the latter. This is where Steely Dan enter. David Hepworth says he can't love Donald Fagen's new record as much as his work of 30 years ago, even though the untutored listener might not be able to distinguish between them. This is simply because he has lived with Fagen's earlier work for years and come to love it.

In this, David gives us a reason why an individual should discount his own future consumption. It's not because of "impatience", as the economic literature claims - a view which Ramsey himself scorned (pdf) as arising "from the weakness of the imagination." Instead, it's because the marginal utility of consumption declines as we age. The pleasure we get from the music we buy in our 20s is generally greater than that we get from the music we buy in our 50s, except in the rare cases when a Hollandesque genius emerges.

And I think this point generalizes beyond music and cultural goods. The utility of going on a binge diminishes with age because hangovers become more painful. When was your best holiday - was it last year, or the one you went on with your teenage mates? And Amy Finkelstein and Erzo Luttmer have found (pdf) that the marginal utility of consumption falls when people fall into ill-health, as the older are more likely to do.

We should, therefore, discount our future spending simply because we'll get less pleasure from £10 spent in 30 years' time than we will from £10 now because the marginal utility of consumption falls with age.

But of course, this reasoning cannot apply to different generations. Quite the opposite. If we put aside our quibbles about interpersonal comparisons of utility aside, this thinking implies that - ceteris paribus - it is better that 20-year-olds have high consumption than that 60-year-olds do. This implies that there's a case for a negative discount rate across generations even though there's a (high) one within any individual. It might be optimal to reduce today's pensioners' spending so that we increase the spending of future generations of young folk (ignoring many other considerations!).

Insofar as this is correct, it makes David Willetts' complaint that oldsters are living high at the expense of youngsters even more worrying - because this is not merely unjust, but undesirable in narrowly utilitarian terms.

Another thing: It is a paradox that Frank Ramsey, who pioneered thinking about intertemporal choice, should have died aged just 26. I reckon there's a moral here.

November 12, 2012

Matches, not men

Ed Miliband says the BBC needs a "strong" DG. It's sad that the leader of a so-called leftist party should still subscribe to a crypto-fascist ideology of strong leadership.

To see my point, start from Lucy Kellaway's entirely correct analogy - that jobs are just like marriages. When we see a marriage we think likely to last, we don’t usually say “she’s like Victoria Coren" but rather “they are right for each other.” The same thinking should be true for jobs. What matters is not getting the “best" person but rather the best fit between the organization’s requirements and the manager’s particular skills.

Research by Boris Groysberg at Harvard Business School has shown just this.He looked at the performance of former executives at General Electric when went onto become CEOs at other firms. He found that where the skills of the executive matched those needed by firms - for example, whether the executive was a cost-cutter, sales grower or manager of a cyclical business - the firm did well. But where there was a mismatch, it did poorly. Managers with similarly impressive CVs, then, can have very different performance.

Football fans, of course, should know this. There are countless examples of coaches doing well with one team and poorly at another. Think of Andre Villas-Boas at Porto and Chelsea, or Fabio Capello at Milan and England, Brian Clough at Leeds and Nottingham Forest. And so on.

What matters, then, is not having a "strong" leader, but rather the right leader. It's the match that matters, not (just) the individual.

In seeking a new DG, what Chris Patten should do is not ask: "who's the best candidate?" but rather "what exactly do we want the DG to do?" and "who has the requisite skills to do this precise job?"

This, though, raises a danger. In defining precisely what the new DG needs to do, there's a risk of over-reacting to current circumstances, and ending up hiring a general who's good at fighting the last war. For example, a DG who's good at cleaning up the standard of journalism might not be good at the many other things a DG has to do. Worse still, the qualities that equip a boss to do well at one task might well mean he does badly in others. For example, the man who is good at improving line-management process is also a stifling micro-manager; the cost-cutter fails to inspire his staff; and so on.

Even if one pays proper attention to matching, therefore, there's no assurance of making the right choice. But at least there's a better chance than there is if you stick to a silly ideology of egomanaical managerialism.

November 11, 2012

The BBC & the myth of leadership

What can chief executives reasonably be held responsible for? This is the question posed by George Entwistle's resignation.

The BBC employs 23,000 people. It is therefore a statistical certainty that there will be occasions of gross incompetence. If there's a great deal of ruin in a nation, there is also a great deal in any organization. To expect one man to prevent an act of idiocy by any one of 23,000 others is, surely, to expect the impossible.

Granted, he might be responsible if he had put in place the systems that generated such poor journalism. But this isn't obviously the case.

Against this, Entwistle is charged with being "incurious George", of not wanting to know what Newsnight was doing. This is harsh. Even leaving aside the fact that Newsnight is a minor programme - its audience of around 700,000 is less than that for Only Connect - any DG must be incurious. All of us have limited rationality, knowledge and attention. It's physically impossible to know everything. As the Vice Chairman of the BBC Trust has written, "‘Inattentional blindness’ is commonplace." The boss who tried to know everything would quickly be accused of stifling his organization by micro-management.

I suspect that what we're seeing with Entwistle's departure is the downside of management as witchdoctoring. We impute powers to chief executives which they do not in fact have with the result that if their organizations thrive we pay them millions but if they don't, we sacrifice them. In both circumstances, we fail to see that their span of control is limited.

Indeed, such a mistaken conception of management, more than Mr Entwistle's failings, might be the BBC's problem. Jeffrey Nielsen has written of the dangers of hierarchy thus:

Rank-based thinking suppresses the heart and intelligence of the majority of an organization's employees. Command and control managing under the influence of rank-based thinking tends to be harsh, coercive and demotivating. It is likely to create a poisonous atmosphere at the organization that kills an employee's natural desire to cooperate and be productive. (The Myth of Leadership, p11-12)

I fear this might have happened at the BBC. If everyone thinks the boss is responsible, they abdicate responsibility themselves with the result that nobody is responsible for anything.

But there is an alternative - what Nielsen calls peer-based thinking. In this, responsibility is diffused across an organization. Shoddy journalism is then the fault of the journalist, not "management" (where "management" means "someone else"), a poor programme the fault of the individual producer, and so on.

In empowering workers, such a business model disempowers management. And those managers who remain cease to be witchdoctors imputed with mythical powers, and become instead humble administrators and are paid as such.

And for this reason, we are likely to be stuck with dysfunctional organizations with absurd notions of "leadership".

November 10, 2012

Interests or preferences?

What is politics for? This is the question raised by Emma when she complains that politicians are "separate and self obsessed, talking to each other in a code designed to stop [voters] understanding or getting involved." Emma's concern is, of course, not confined to the left. The desire to "engage" with voters lies behind Dorries' decision to appear on I'm a Celebrity and Cameron's "mad idea" to appear on This Morning.

But it's not just the voters that politicians are distant from. On fiscal policy, tax policy and - especially - immigration, politicians are as disengaged from experts as they are from voters. Emma is flat wrong to say that "If you don’t have an academic career or a string of publications behind you, it can be a struggle to have your voice heard." The likes of Simon Wren-Lewis or Christian Dustmann have as much influence in Whitehall as a welfare recipient.

The problem here is that, in at least some important ways, there's a massive distance between what voters want and what's good for them. Politicians cannot be both populists and technocrats, therefore, and end up being neither, disengaged from both "ordinary voters" and from expertise and evidence.

This raises a question which should be made explicit: should politics serve the preferences of voters, or their interests?

Max and Hopi seem to think the latter. They say that politicians must tell voters when they are wrong, when their preferences don't serve their interests.In saying this, they echo Burke:

Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion...

If the local constituent should have an interest, or should form an hasty opinion, evidently opposite to the real good of the rest of the community, the member for that place ought to be as far, as any other, from any endeavour to give it effect.

Against this, I fear that those who want more "engagement" with voters seem to want politicians to defer more to voters'preferences.This raises the danger of falling into X Factor politics - an ill-informed choice between a limited field of inadequate candidates, the winner of whom quickly fades into disappointing mediocrity.

In a world where voters are (rationally?) ignorant about policies, should politics really be just another form of marketing and consumer choice?

November 9, 2012

Nate Silver's diminishing returns

Nate Silver's successful prediction of the election outcome should be celebrated as a triumph of science over waffle-monkeys and reality-deniers. But I fear there's a danger here.

His success should have two consequences: others should emulate his methods; and those who this time bet against his forecasts on the basis of wishful thinking will be unlikely to repeat their error.

This means that it will be harder to make money by betting on the next election, as markets will be pricing in more scientific method and less flim-flam.

How, then, will a Nate Silver wannabee make money with such poor odds? He can only do so by betting with borrowed money - in effect leveraging up to improve his returns.

But this carries two dangers. One is exposure to tail risk, as even the best methods occasionally go wrong: as Nate said, 8% chances do come up once in a while.

The other is performativity risk. If voters believe that a particular candidate is likely to win, they might not turn out. Because the leading candidate - by definition - is the one who attracts widespread but lukewarm support, he might be more vulnerable to this, which would put the election result back into doubt.

On both counts, our Nate wannabee risks losing a lot. He is, in Taleb's phrase, hoovering up pennies in front of a steam-roller.

What I'm describing here is no mere possibility. It's a pretty close analogy to what happened with mortgage derivatives; people geared up, thinking they were onto a safe way of making money but in fact were magnifying risk rather than reducing it.

This is an example of what Andrew Lo calls adaptive markets. A smart guy (Nate Silver) sees a way of making money, but as people emulate him, profit opportunities turn into losses. Just as there are population cycles in biology, so there are profit cycles in finance: the waxing, waning and waxing again of returns on small cap stocks since the 1980s is just one example of this.

And it's not just in financial markets that this is true. Billy Beane and his hero Arsene Wenger (pbuh and a painful death to his enemies) have seen their success dwindle as lesser men emulated them (though perhaps this also shows that big money beats brains).

The message here is that intelligence, science and ability might make you money - but perhaps only briefly, and trying to repeat your tricks can lead to losses.

November 8, 2012

Performativity in policy

John Kay writes:

The contrast between the work of the [Roskill Commission in 1968-71] and the dismal quality of the material supporting the proposed new high-speed rail link to Birmingham is a measure of how far standards of evidence in policy making have declined.

Good judges share his lamentation about policy formation. And this is not a partisan issue; look at Labour's drugs policy, for example.

However, on the other hand, most of us would agree that, in important respects, economic policy is better now than it was at the time of the Roskill Commission, when we had prices and incomes policies, fixed exchange rates and an industrial policy that obsessed about British Leyland.

This raises a paradox. How can policy-making be both better and worse than it was 40 years ago? Here's a suggestion (only that). It's that the "neoliberal" turn in politics has two adverse effects:

1. If you believe markets know best and that centralized information-gathering is bound to be a deeply flawed process, then you'll invest less effort in it, or be sceptical of the product of doing so. Cost-benefit analyses will then be founded upon flimsier evidence, or won't carry much weight even if it is.

2. The increased belief in consumer sovereignty and decline in faith that "the man in Whitehall knows best" (to which "Nudge" economics is the counter-reaction) has devalued expertise. If politics is about giving voters what they want, you don't need experts and evidence, but just pollsters and market researchers.

In these senses, "neoliberalism" has had some performative effects upon policy. It doesn't just describe the world (whether well or not is another issue), but helps to create it.

November 7, 2012

Why celebrate entrepreneurship?

Luke Johnson celebrates entrepreneurial culture:

My sense is that the present cohort of graduates and twentysomethings is far braver than I was. The entrepreneurial culture has never been more lively, and I am confident that in the coming years there will be hundreds of brilliant new enterprises led by this generation of risk-takers, who opt to control their own destiny.

This runs into Rick's objection, that self-employment is nothing to celebrate, as it is a symptom of economic failure.

So, who's right - Rick or Luke? Four things make me side with Rick:

- Entrepreneurs are often jacks-of-all-trades. An entrepreneurial society thus doesn't make best use of the division of labour.

- Self-employment, especially now, is a form of under-employment; people sitting around waiting for the phone to ring.

- Micro-businesses suffer from financing constraints to a greater extent than large firms do. This can prevent them reaching optimal size.

- Many of the self-employed actually want to be relatively unproductive. They see self-employment as a better way of combining work with their commitments to children or the golf course.

There are good reasons, then, why economies of entrepreneurs are often low-productivity ones. Small businesses are very often not tomorrow's giants or job creators, but rather just mediocre plodders - if they survive at all.

So, is anything to be said for Luke's view? Two things:

1.Entrepreneurship is a way of escaping the "pinheaded weasels" - middle managers who stifle creativity and job satisfaction and who divert energy away from production and towards rent-seeking and productivity. Granted, good middle-managers are valuable (pdf), not least because they can channel corporate bullshit into useful work. But good managers are not necessarily the majority (pdf).

2.It could be that the costs of organizing production through market contracting has fallen relative to the costs of organizing internally. To this extent, it makes sense for the numbers of freelancers and subcontractors to rise relative to the numbers of employed. Now, this varies from business to business so generalizations are tricky. But one factor here is the decline of mass production. When firms needed routine workers to ensure that assembly lines kept running, it made sense to employ them directly and order them about; there's a reason why assembly line workers were rarely freelancers. But if firms now comprise bundles of discrete projects, market contracting - the hiring of specialists for occasional work - makes sense. This is especially true if their output can be easily measured, thus avoiding haggles over whether contracts have been fulfilled.

Sadly, though, it's not clear to me whether the drive towards subcontracting and freelancing, where it exists, is driven by pure Coasean (pdf) reasoning, or whether it is instead motivated by a desire to shift risk from firms to workers and suppliers.

However, the justification for entrepreneurial culture might not lie in narrow economics, but in other things. For example, the self-employed tend to be happier. And a society of independent(ish) entrepreneurs rather than corporate drones will be one of different values. As someone said, "The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life."

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers