Chris Dillow's Blog, page 166

October 26, 2012

Moral licensing & cherry-picking

It's a commonplace that people sometimes do good deeds to expiate their sins. What's not quite so well appreciated is that the opposite also happens; doing a good deed gives us licence to behave badly. A new paper establishes this experimentally. Researchers got people to play a sequence of simple dictator games. And they found that the dicators' decisions on how much to give away was not constant but rather cyclical; high donations followed low ones and low ones followed high. People who behaved altruistically once behaved selfishly the next time:

Donations over time seem to be the result of a regular pattern of self-regulation: moral licensing (being selfish after altruist) and cleansing (altruistic after selfish).

Moral behaviour, then, far from being a stable effect of our character, seems to be cyclical. The word "error" appears in "fundamental attribution error" for a reason.

This is not always a bad thing. As Anna Merritt and colleagues say (pdf), moral licensing can give people the wiggle room to make necessary but morally unpleasant choices - for example, a doctor having to choose which ill patient to treat.

But here's my concern. Robert Cialdini has shown how, sometimes, people over-reciprocate. A small initial favour, he says, can yield large favours in response. Could a similar thing be true for moral licensing, whereby we feel that smallish good deeds give us licence to do large bad ones?

Two things make me fear so. One is simply that humans have great capacity for self-justification: "they won't miss the money"; "she's up for it really" and so on. Big misdeeds thus shrink quite easily.

The other is yet more experimental evidence.Tobias Regner and Gerhard Riener got people to play a trust game, in which two trustees were given the choice to repay the trust a third person had put in them. They asked: how does a trustee act, if he sees his fellow trustee's behaviour? They found that when the first trustee did reciprocate, 36 of 43 followers did not. And when the first trustee didn't reciprocate, 14 of 15 followers didn't. In other words, whatever the first trustee does, the second overwhelmingly behaves selfishly.

What's going on here, say Regner and Riener, is moral cherry-picking. People choose the motive that promotes their self-interest.So if the leader reciprocates, the follower thinks "the obligation to the trustor has been repaid already, so I don't need to do so." And if the leasder doesn't reciprocate, the follower thinks "Hey, there's nothing wrong with not reciprocating - I'm only doing the same as the other fellow."

You might - if you wish - see an application of this to current scandals.But that's not really my point. Instead, I'm agreeing with Norm; you don't have to be a conservative to fear that our moral conduct is fragile, and we have impulses that need restraining.

October 25, 2012

Support the undeserving poor

Murrary Rothbard asks:

Why won't the left acknowledge the difference between deserving poor and undeserving poor. Why support the feckless, lazy & irresponsible?

I'd answer thusly:

1.I'm surprised a libertarian is asking. Two of the great and correct insights of libertarianism are that the state has very limited knowledge, and that its interventions often lead to people gaming the system. This is true of welfare spending as of anything else. The government doesn't have the knowhow to distinguish well between the deserving and undeserving poor. And its efforts to do so are not only expensive - in terms of paying bureaucrats and corporate scroungers and fraudsters - but also bear heavily upon the honest and naive deserving poor whilst the undeserving, who know how to game the system, get off.

2. There's another way in which trying to distinguish between deserving and undeserving poor can be expensive. What looks like a reluctance to work might instead be practicing one's skills in preparation for high earnings later. If the state had forced benefit claimants to work in the early 90s, we might not have had Oasis or the Harry Potter novels, and the tax revenue they generated.It doesn't take many multi-million pound earners to pay for a lot of the £3692 annual Jobseekers' Allowance paid to "scroungers".

3.The lazy are a minority of the unemployed. The ONS says (Excel file) that only 16.3% of the unemployed have high life satisfaction (9-10 on a 0-10 scale) whilst 45% have low satisfaction (0-6). The equivalent figures for the employed are 24.4% and 20% respectively. With the lazy in a minority, it's harder, and so more expensive, for the state to identify them.

4. What looks like laziness might be an endogenous (pdf) preference. If someone has looked for work and not found it, they might eventually, sour-grapes style, decide not to try. Why should people be punished for reconciling themselves to their situation?

5. If you want to help the deserving poor, subsidizing the lazy to stay on the dole might be a good way to do so. For one thing, it reduces competition for jobs and so gives the deserving a greater chance of getting work. And for another thing, if you deprive the "irresponsible" of an income you don't just increase their incentive to find useful work. You also increase their incentives to commit crime. The deserving poor might thus find themselves the victims of more mugging and burglary.

6. Given that it is costly to do so, should the state try to legislate for morality? I would have thought that libertarians would say no, and that morality should instead be enforced through social norms, such as ostracising and stigmatizing scroungers.I can see why libertarians might be opposed to all welfare spending on Randian or Nozickian grounds, but I find it hard to see why they think a welfare state should try to discriminate between deserving and undeserving.

I don't say this to say there shouldn't be incentives to work. I would prefer a basic income system in which there were such incentives, but in which an income is also paid to the undeserving.

I give the last word to that great political philosopher, Ned Flanders:

Todd: Daddy, what do taxes pay for?

Ned: Oh, why, everything! Policemen, trees, sunshine! And lets not forget the folks who just don't feel like working, God bless 'em!

October 24, 2012

The economic policy dilemma

Tim endorses business rates as a "close approximation to a Land Value Tax, the least distorting of all taxes."

He omits to add that they are also very unpopular - which is one reason why they raise only 1.6% of GDP*. Their domestic equivalent, rates, were, remember, abolished in 1988 and (eventually) replaced with the less onerous council tax. This tells us that there is very little support for Land Value Tax.

This reflects a widespread problem in economic policy-making, which I express through the medium of a Venn diagram thusly:

This doesn't just apply to land taxes, but to numerous other things: immigration; Keynesianism (Osborne's policy is more popular than Labour's); a citizens' basic income; worker democracy; drug liberalization; fiscal union in the euro area. And so on; feel free to add others.

In saying this, I'm not taking a left-right stance. Marxists have long thought public opinion warped by false consciousness; the libertarian Bryan Caplan has challenged what he calls the "myth of the rational voter", and the Democrat-supporting Alan Blinder has said (pdf):

Ideology seems to play a stronger role in shaping opinion on economic policy issues than either self-interest or knowledge...The contrast with homo economicus—who is well informed, nonideological, and extremely self-interested—could hardly be more stark.

However, I fear that blaming public stupidity is only part of the problem. It's also the case that economists' association with the charlatanic practice of forecasting has helped to discredit the profession even where it has useful things to say.

Whatever the cause, the fact is that there is a sharp trade-off between democracy and good economic policy-making.

* Table 4.6 of this pdf.

October 23, 2012

Boardroom quotas: some issues

European commissioners are thinking of demanding quotas for the number of women on company boards. This raises some issues.

Issue one is about selection effects. Imagine - which shouldn't be hard - a world in which there are very few women directors. A company which appoints one is therefore, by definition, unusual - perhaps in being more forward-thinking. And the woman it appoints is also likely to be unusual, perhaps especially talented. The data might then show that companies with women directors do well. But this is because of a selection effect that could go into reverse if all firms were compelled to appoint women, some of whom might be mediocre.

However, selection effects needn't work positively. They can be adverse. Let's grant that there's some evidence that women - on average - would help companies make better decisions by virtue of their gender, say because they are less overconfident, more risk-averse or have higher ethical standards. (Whether these differences are innate or due to social constructs is irrelevant for my point). It does not follow from this that companies that appoint women would be better-run. This is because the women it appoints might not have these feminine virtues but might instead have gotten to the top by virtue of being more ballsy than men. If this is the case, "free" appointments of women might actually reduce the amount of feminine attitudes on boards. By contrast, quotas - insofar as they compel boards to appoint feminine women - might actually enhance performance.

These competing selection effects might explain why studies of the effect of women directors upon corporate governance have been so ambiguous; some find a positive effect, some a negative (pdf), and some a U-shaped one. The question is: which selection effect would predominate if quotas are introduced?

The second issue is: why quotas? There are many possible ways of improving corporate governance: decentralizing management; having more worker-directors; preventing reckless takeovers; preventing narcisscists, sociopaths or psychopaths from becoming CEO; encouraging shareholders to exercise proper control, and so on. Why, of all the possible ways of improving corporate governance, should quotas for women be top of the list?

Thirdly, if there should be quotas to ensure boardroom diversity, why confine them to women? Why not quotas for ethnic minorities or gays?

One possibility is that women bring something to boardrooms that other minorities don't, by virtue of the gender differences I've mentioned. But as I've said, there's no guarantee that women appointees would necessarily possess such characteristics. If you want less overconfidence and reckless risk-taking on boards, why not mandate appropriate psychometric tests rather than worry about the shape of genitalia?

Which brings me to a final issue. I suspect that what we're seeing here is not so much an attempt to improve corporate governance as a paradox of equality - the paradox that, by the time a group is powerful enough to press for equality, the need for such equality has diminished.

The time when women most needed legal protection in the workplace was in the 60s and 70s, when they were "dollybirds" to be raped at will. But women then lacked the political power to achieve their rights. Only now are they are politically strong enough to demand laws to ensure their boardroom representation - and yet their economic position is strong enough that they can (up to a point) achieve such representation without the need for law.

I don't say all this to argue against gender quotas; anything that frustrates careerist men has something to be said for it. But let's not think this is much about corporate governance.

October 22, 2012

Which market failure?

Liam Halligan says: "The UK remains in grave danger of a sovereign bond market meltdown." This puzzles me.

I don't disagree that there's a good chance of bond yields rising over the long-term. But a return to normalish interest rates that is anticipated by the market - an upward sloping yield curve implies that investors expect yields to rise - is not a "meltdown."

Instead, Mr Halligan is, I guess, making a stronger claim - that government bonds are now mispriced; long-term real yields of around zero are not pricing in any "grave dangers."

But if there's one market you'd expect to be efficient it is, surely, the sovereign bond market. It's a large, liquid market in which there is little private information and countless intelligent buyers none of whom have pricing power. But Mr Halligan seems to be saying that even this market is inefficient, that it is misallocating trillions of pounds of capital; the world sovereign bond market is worth some £26.6 trillion (pdf).

If you think sovereign bond markets can misallocate resources on a massive scale, you got to believe that ordinary markets for goods, labour and services are even more prone to huge misallocations.

It's quite coherent to believe there's a "grave danger of a sovereign bond market meltdown" if you are sceptical about the functioning of markets generally. But how can you do so if you believe in free market policies? (It should be obvious that I'm not having a go at Mr Halligan specifically here; I suspect lots of conservative-minded folk think similarly).

One possibility is that you think that governments and regulators are even more incompetent than private sector agents, and so even if the market is inefficient, state intervention is more so. But I'm not sure this applies in this case. Mr Halligan is claiming that someone does have the ability to identify market malfunctions - himself. Why can't the state draw upon such reserves of competence?

Another possibility is that markets are "micro efficient but macro inefficient". This might be true of asset markets - for example it's possible for gilts to be overpriced even if (say) seven year issues are correctly priced relative to five-year ones. But to claim that goods and services markets are micro efficient is surely a big ask.

A third possibility is that one recognizes the ubiquity of market failure but favours limited government for other reasons - say because you value (negative) freedom or because even malfunctioning markets are conducive to economic growth.

This is, I think, coherent. But there is, nevertheless, an inconsistency here. Mr Halligan wants the government to do something about the (possible) failure in bond markets - cut spending. But he - and more significantly those who think like him - seem relaxed about the failures in goods and labour markets that cause at least 2.5 million people to be out of work.

It's strange how some market failures demand action and some don't, isn't it? If I didn't know better I'd suspect the right of merely pursuing class interest without regard to intellectual consistency.

Another thing: Mr Halligan claims that such a meltdown would have disastrous effects. This too is questionable.

October 19, 2012

Takeovers: an agency problem?

The Treasury Select Committee says the FSA "should and could have intervened in RBS’s takeover of ABN AMRO."

Really? This runs into the objection raised by Hector Sants (par 23) - that the regulator shouldn't be "a 'shadow director' protecting firms from poor commercial decisions." An intelligent regulatory regime - which hindsight tells us didn't exist in 2007 - would allow firms to fail through their own stupidity.

Where there is a case for the regulator to intervene in takeovers is if some market failure is involved. The obvious such failure - that takeovers reduce competition - did not apply in the RBS/ABN Amro case. But might another failure have been involved that justifies the TSC's stance? A paper by Thomas Gall and Andrea Canidio suggests maybe, because there can be failure in the principal-agent relationship between shareholders and management.

Imagine, they say, that an agent can choose between two tasks: a routine one and a complex, high-profile one such as launching a new product. If the agent wants to signal that he has high ability, he might well prefer the latter. But this could well be inefficient from the firm's point of view - because such projects distract employees from important but mundane tasks, or because the payoffs to such projects are small or uncertain. In this case, they say:

Idleness can be desirable for a principal if, because of career concerns, employees have an incentive to over-invest in complex, visible tasks that generate signals about the agent's ability...To balance their employees' bias toward visible tasks, fi�rms may distort their organizational investments toward employee perks that are complementary to idleness. That is, employee perks that seem to encourage idleness are actually meant do so.

They cite the contrast between Google, which offers lots of strange perks to employees, and Apple, which doesn't.

Doesn't this line of thinking apply to CEOs too? Often they want to undertake mergers because of the buzz of the deal or for ego gratification (pdf). But such mergers are often (pdf) bad for shareholders, as was pointed out at the time of ABN's takeover.

Herein, you might argue, lies a case for regulation. Contracts between principals (shareholders) and agents (CEOs) fail to solve the problem identified by Gall and Canidio. They over-incentivize CEOs to do big deals, and under-incentivize them to stick to their knitting and focus on running companies well day-to-day. Regulation is then needed to rein in CEOs egomania and hubris.

However, that word "might" is doing a lot of work in that paragraph. Shareholders can in theory stop CEOs doing deals: there's nothing to stop them writing a contract forbidding them to aquire "assets" over a certain size." But they don't do this. This is not (just) because they lack power over CEOs, but because they too often get carried away by bid euphoria; shareholders, remember, approved RBS's takeover of ABN AMRO.

Perhaps, then, shareholders need protecting not (just) from self-interested CEOs, but from their own carelessness. Which raises the question: if shareholders need an organization as sloppy as government to protect them, what useful function are they serving?

October 18, 2012

Jungles, matches & optimality

Amidst all the celebration of Lloyd Shapley and Alvin Roth's Nobel, there's something nagging at me.

Their achievement was to show, theoretically and empirically (pdf), that we don't necessarily need a price mechanism to produce an allocation that is stable and Pareto optimal. Another process can do so, which works for matching students to schools, kidneys to recipients and for marriages, among other things.

But there is another mechanism that also achieves such a result. It's Ariel Rubinstein's jungle (pdf) economy. He shows that, under certain conditions, allocating scarce resources to the strongest agents according to their preferences will also give a stable, Pareto optimal equilibrium.

And, of course - in theory and under some conditions - a free market will also achieve this.

We have, then, not one or two but three ways of getting to a stable Pareto efficient outcome.

However, most of us, I suspect, don't think Rubinstein's jungle economy an especially pleasant place to be - even though it achieves the same desiderata as the (theoretical?) free market and Shapley-Roth process: stability and Pareto optimality.

Which raises the question: what do the latter have to make them desireable that the jungle economy lacks?

I don't think economic growth is the answer: ceteris paribus, I would rather live in a free market economy with zero growth than in a zero-growth jungle economy.

Nor is it that the market and matching economies do away with the power that generates the jungle allocation. One feature of Shapley-Roth processes is that they favour the side doing the choosing. Power thus helps determine allocations, as in the jungle.

Nor is it sufficient to say that the Shapley-Roth process saves lives. It does, but Rubinstein claims that the jungle allocation also does so by removing the need for violence.

And I don't think it's good enough to make the empirical claim that we in fact rarely see Rubinstein's jungle economy working as well as theory implies: the same is true for free market economies.

What I'm edging towards here is a point made (pdf) - in a different context - by Amartya Sen, that Pareto optimality isn't as great an ideal as economists think.If you can't abolish slavery without making slave-owners worse off, then slavery is Pareto optimal.

To return to the question: why do we cherish the market economy over the jungle economy? I suspect one reason is Deirdre McCloskey's - that a market (sometimes) promotes more attractive virtues than other societies. It is, perhaps, significant that the English have a longer tradition of freeish markets than the Serbians.

And this is where my nag arises. If Pareto optimality is not sufficient to make an allocative mechanism attractive, what else is needed, and do Shapley-Roth processes possess it?

October 17, 2012

In defence of the structural deficit

Tim Worstall points to the estimate* that the UK ran a cyclically adjusted government deficit of 5.2% of GDP in 2007 and says:

It’s really most unKeynesian to be running a deficit of that sort of size at the top of the longest boom in modern history, isn’t it?...

Keynesianism doesn’t work..because policitians will never run the associated surpluses in the booms.

However, I'm not sure this episode supports Tim's scepticism. The structural budget deficit is the sort of pseudo-scientific concept that brings economics into disrepute.

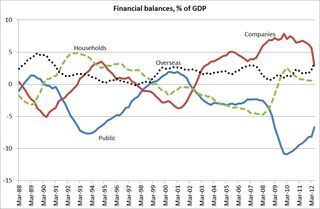

Let's imagine GDP is at its potential level. What should government borrowing be? It all depends upon the private sector's financial balance; this, by definition, is the counterpart of the government's financial balance. If the private sector has a net deficit - because it is investing more than it is saving, then the government will have a surplus. And because, ex hypothesi, GDP is on trend, it'll have a cyclically-adjusted surplus.This is what happened in the late 80s.

If, however, the private sector has a surplus, then the government will have a deficit. This is what happened in 2007.Companies and foreigners were then running surpluses. So someone had to run a deficit. Because households weren't running a big enough deficit, that someone had to be the government.

To put this another way, companies weren't investing as much as they should have, and foreigners weren't buying enough of our goods. Government spending filled the gap. Yes, economic activity was strong. But this was because the government ran a deficit to sustain economic activity. In this sense, the deficit was entirely consistent with orthodox Keynesianism.

Two things make me say that the government was a passive responder here, rather than a profligate borrower:

1.As the government deficit rose, real interest rates fell; long-dated linkers yielded 1% in late 2007, half the rate they did in 2003. This is consistent with a savings glut - by foreigners and corporates - driving down real interest rates, which the government tried to resist by borrowing more. If markets had been spooked by a "structural deficit" in 2007, rates would have risen. They didn't.

2. Inflation was quite well-behaved in the mid-00s; it ended 2007 at 2.1%, near enough bang on target. This suggests the government deficit was not adding much to inflation, as not overheating the economy.

You might object that whilst there was little goods and services inflation, there assuredly was house price inflation.

True. But this was, arguably, despite the fiscal deficit, not because of it.Imagine the government had tried to run a surplus in the mid-00s in the face of the corporate and overseas savings gluts. This would have added to the incipient weakness in activity. The Bank of England would have responded by cutting interest rates. And this might have raised mortgage lending and house price inflation even more.In this sense, one could criticise the Labour government for not running a big enough deficit - for not doing enough to raise interest rates to choke off what proved to be a ruinous asset price bubble.

Now of course, you can criticize Labour for spending badly, and for choosing to spend rather than cut taxes. But you shouldn't blame it for running a deficit. And you shouldn't think it anti-Keynesian to have done so.

* I think the Telegraph report is referring to statistical table 2 of this pdf: old media aren't good at links.

October 16, 2012

Policy beyond forecasts

The OBR has published a long report on why it got its GDP forecasts wrong. This is an exercise in missing the point.

We don't need a 99 page document to tell us why the forecasts went wrong. They went wrong because that's what forecasts do. The future is inherently unknowable, so forecasts will very often be wrong.

Getting a forecast wrong is no crime. What is deplorable is basing a policy upon something as unreliable as a forecast. Blaming economic forecasters often serves a political function. It deflects blame for bad policy away from those in power - be they politicians or bosses - and onto economists.

The question we should be asking is: can we base macroeconomic policy upon something more robust than a forecast?

In monetary policy, the answer could be yes: one purpose of the Taylor principle is to take forecasting out of policy. Granted, a forecast is implicit - inflation and the output gap matter because they are thought to predict future inflation - but the principle doesn't waste time on formal forecasting.

The analogue in fiscal policy is the automatic stabilizer; as GDP falls, so taxes fall and welfare spending rises, helping to moderate the recession. Such stabilizers, however, aren't sufficient to fully describe how fiscal policy should be set. Hence the debate between Keynesians (or Kaleckians!) and Austerians. Insofar as this debate rests upon very fallible economic forecasts, it is, however, unsatisfactory.

Hence my question: could fiscal policy become more automatic, more state-dependent - as the Taylor principle envisages monetary policy - and less forecast-dependent?

In one sense no. There are awkward administrative issues in having state-dependent increases or decreases in infrastructure spending. The rule "build a new airport iff the output gap exceeds x%" is probably impractical. There are, though, three other possibilities:

1.Have a bigger government sector. As Dani Rodrik pointed out years ago, open economies tend to have bigger governments. This is because such economies are more vulnerable to unforeseeable risk, and having a bigger state sector is a way of offsetting those risks.

2. Have stronger automatic stabilizers - for example, higher marginal tax rates or higher benefit levels.

3. Have a system of job guarantees, in which the state (or local government) acts as an employer of last resort.

Now, my rightist readers will point out that there are drawbacks to all three of these solutions. They are right - though how much so I'm not sure. This is because there's a fundamental trade-off; policies that reduce risk tend also to blunt incentives.

Without such policies, however, there will be pressures on governments to use discretionary policy. But if this relies upon a sill "predict and control" mentality, it too has large costs.

Another thing: There is, if you'll allow the phrase, a third way here. Having active markets in GDP securities and other macro risks would allow those exposed to recession risk to buy insurance against it.This would reduce the need for governments to try (unsuccessfully) to prevent such events. However, I fear that Robert Shiller and I are the only two guys on the planet who think this might be a good idea.

October 15, 2012

Abortion: more than rights

Is it possible to have a non-emotional debate about abortion? Mehdi Hasan fears not. The debate, he says, has become one of a clash of incommensurable ideas: the right to life of the unborn baby versus a woman's right to choose.

Framing the debate this way, however, misses at least five things. I mean:

1. How should we describe the abortion decision? Is it the termination of a potential birth, or merely the postponement of one?

Often, a woman has an abortion because she just doesn't feel emotionally or financially ready for the responsbility of being a mother. This is why abortion rates are three times (pdf) higher for under-18s than they are for 30-34 year-olds. A "woman's right to choose", then, is often not just a matter of choosing whether a foetus lives or dies. It is a matter of choosing whether to have a child in 2012 or, say, 2017.

2. If an abortion is the postponement of a birth, the question ceases to be: "does a foetus have a right to life?" and becomes: does a foetus have a right to life at the expense of a person yet to be conceived?

Put this way, we can answer Mehdi's question: "Who is weaker or more vulnerable than the unborn child?" The answer is: the unconceived one.

Two answers here are impermissible. One is that a foetus might be viable outside the womb. This fails because, as Owen Barder has said, rights cannot be contingent upon medical technology. The other is the argument from religion; this fails because it means nothing to non-believers.

This drags us into the question of the moral status of yet-to-be conceived persons and the non-identity problem. These are tricky issues, but very few people think we should be unconcerned about future, unconceived, people; worries about government debt or climate change are just nonsense if we take this view.

3. If an abortion is a postponement of birth, and so doesn't affect the size of the future population, doesn't utilitarianism argue for allowing abortion?

The argument here is that a child will have the best possible life, the better its upbringing, and if women can choose when to have a child, they are more likely to do so at a time that maximizes the quality of that upbringing.

Put this way, the argument for giving women a "right to choose" can be based not (just) upon self-ownership, but upon the idea that they are local experts best able to assess the well-being of future persons.

4.What if abortion is not a mere postponement of birth, but a way of restricting the size of the future population? You might argue on utilitarian grounds that this means abortion is a bad thing, as it prevents people being born whose lives would be worth living. Or you might argue that such reasoning leads to the repugnant conclusion.

5. Externalities matter. One could argue that banning abortion imposes a negative externality onto others. This is because in forcing women to have children they'll resent and bring up badly, we'll end up with a larger number of young people predisposed to crime. Granted, the claim that legalized abortion was responsible for the drop in crime in the US (pdf) and UK is econometrically (pdf) contested. But to me, it is intuitively plausible.

I don't say all this to take a stand on abortion; none of you should give a damn about my opinion. I do so merely to point out that there is more at issue here than a clash between a "right to life" and a "right to choose".

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers