Chris Dillow's Blog, page 169

September 17, 2012

"Black Wednesday": two paradoxes

20 years ago yesterday, sterling left the exchange rate mechanism. This episode raises two paradoxes that haven't had the attention they should.

Both exist only if you accept the hypothesis that the conduct of monetary policy since 1992 has been better than what went before. I don't think this is wholly unreasonable. Granted, it's still controversial as to how much post-1992 monetary policy contributed (pdf) or not to the "great moderation" of 1992-2007. And inflation targeting might be inferior to NGDP targeting.But nobody really now thinks inflation targeting is inferior to monetary or exchange rate targets. So in this sense, there has been some progress.

Conditional upon this assumption, my first paradox is this. The decision to join the ERM followed years of intense discussion among economists and yet proved to be a bad one, whereas the decision to adopt inflation targeting was taken hurriedly and yet proved a better idea*. This suggests that cool-headed, lesiurely and informed policy-making after lengthy debate isn't always better than quick panicky decisions.

Leaving the ERM created the conditions for a long period of strong growth and falling unemployment. How far this was due to the falling pound, to lower interest rates or to inflation targeting itself is unimportant for my purposes. Despite this, the move led to a drop in Tory support from which the Major government never recovered, and the day was long known as "Black Wednesday"; efforts to rename it "Golden Wednesday" never succeeded.

Which gives my second paradox: a government that takes a decision that's good for the economy can actually suffer from doing so. I don't think this is because voters blamed the government for taking us into the ERM in the first place. For one thing, that decision did not prevent the Major government winning the 1992 election. And for another, the decision had bipartisan support; Labour's 1992 manifesto promised to "maintain the value of the pound within the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.**" Instead, I suspect the Major government suffered from being seen as too weak to defend the pound, even though such weakness was good for the economy.

Putting these two paradoxes together suggests something curious - that informed expert opinion on economic policy can sometimes be wrong, and so can voters.

* Milton Friedman had suggested (pdf) price-level targeting in 1968, but by the early 90s there was little interest in the idea in the UK.

** An interesting exercise in counterfactual history would be: what would have happened if Labour had won the 1992 election and been forced out of the ERM? It would have suffered a reputation for bad economic management, and we'd not have had a New Labour victory in 1997.

September 16, 2012

The Tories' class base

The Brittania Unchained Tories' attack on "lazy" workers and demand for even fewer workers' rights has been widely criticized. This prompts the question: why have the Tories been reduced to such drivel?

Here's a theory - it's because such policies offer one of the few ways of uniting the otherwise fragmenting class interests underpinning Tory support.

One remarkable feature of the Conservative party since the late 19th century has been that it has been the party of most of the rich.It has more or less successfully represented the interests of land-owners, rentiers, industrialists and commerce.

This was not always the case. Before Robert Peel, the Tories tended to represent (some) landed interests in opposition to Whigs' support for commerce; this most famously manifested itself in the fight over the Corn Laws.It was a miracle of political reinvention that converted the Tories from the party of the squirearchy to that of the beerage.

But this alliance of intrests of the rich is now fraying, in at least two ways:

- Business wants to build on the green belt and have a third runway at Heathrow. But many wealthy homewners don't want this. The commercial and property interests thus clash.

- Business wants cheap and plentiful money, but savers don't. QE is the euthanasia of the rentiers, which - unsurprisingly - rentiers aren't keen on.

In these senses, some high-profile policies jeopardize the alliance of interests backing the Tories.

And this is where Britannia Unchained comes in. Attacking workers might not make much economic sense, but it is one of the few economic agendas which could unite the otherwise fissiparous interests of Tory supporters.

I don't mean to say that Raab and his colleagues are consciously doing this - but then the Tories have often had a tacit, intuitive ability to shore up their support.

What I am doing, though, is raising a question. It's long been a cliche that Labour's class base - industrial workers - is shrinking and fragmenting. But might the same be also true for the Tories?

Freedom & learning

Norm channels John Stuart Mill:

It is a commonplace of political liberalism that discussion and debate are good; we learn through considering different points of view, including those to which we are opposed. Commonplace because true.

Really? At least one famous study (pdf) has found that we don't learn from considering different points of view. Quite the opposite. Back in 1979 Lee Ross and colleagues got supporters and opponents of capital punishment to read arguments against their beliefs.Far from causing people to learn, this had the opposite effect:

The result of exposing contending factions in a social dispute to an identical body of relevant empirical evidence may be not a narrowing of disagreement but rather an increase in polarization...Social scientists can not expect rationality, enlightenment, and consensus about policy to emerge from their attempts to furnish "objective" data about burning social issues.

What's going on here is the confirmation bias (pdf). People give great weight to evidence which supports their priors whilst giving contrary evidence critical scrutiny. And that's if they even see such evidence. It's widely thought that the increased freedom of speech which the internet has given us exacerbates the tendency towards filter bubbles and echo chambers in which people create a "Daily Me" which corroborates their prejudices.

Discussion and debate lead not so much to learning as the mere exchange of prejudice. Free speech gives us not a rational pursuit of truth but rather the mindless and often dishonest ventings of "Sam Bacile", George Galloway, Kelvin Mackenzie and countless other fanatics. Mill's defence of free speech seems to have been a rationalist Victorian optimism which isn't supported by the evidence.

Or is it? Two things suggest otherwise:

- In academia, free expression is a necessary condition for scientific progress, though not a sufficient one; it must be supplemented by peer review and benchmarking theories against evidence.

- Western societies which have enjoyed long periods of free expression have enjoyed what Norm and I would regard as progress towards truth, in the sense of increased equality for homosexuals, women and ethnic minorities. There might be a causal link here.

On balance, I suspect Mill's consequentialist argument for free speech is weak. If it is to be rescued, it's by pointing to the tiny fraction of intelligent expression it permits, rather than to the vast majority of worthless out-pourings.

This, though, is not to argue against free speech. Rather, I mean to suggest that the argument for it should be a non-consequentialist one. Quite simply, nothing - not majority opinion, national security, decency or the will of God - can be sufficient licence to suppress it.

September 14, 2012

Why not left-libertarianism?

Sam Brittan wants the Lib Dems to become left-libertarian. This is like the suggestion that I marry Victoria Coren - a nice idea, but it won't happen. Lib Dems are vote-whores, and there are no votes in left-libertarianism.

Why not? It's not because left-libertarianism lacks merit. As I've said, it doesn't. To a large extent, it is just the political expression of the second theorem of welfare economics.

Instead, one reason is that there are strong cognitive biases which undermine support for both equality and liberty. Another reason is that, because left-libertarianism get no attention in the media, it loses from the mere exposure effect.

But there might be another reason why left-libertarianism is so unpopular. It lies in Jonathan Haidt's The Righteous Mind. He says that just as our tongue has taste receptors, so our moral mind has moral receptors. There are, he says, six of these: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation and liberty/oppression.

The problem with left-libertarianism is that whilst it appeals to the liberty receptor, it doesn't appeal much to the others. For example:

- Support for stringent inheritance taxes are thought to violate the sanctity of family life. Relations between father and son are considered more inviolable than those between employer and employee.

- Support for free migration is seen as disloyal to existing communities.

- An unconditional citizens basic income gives people something for nothing and so undermines norms of reciprocity and our instinctive hatred of the idea that people might take a free ride on our efforts.

- The opposition to paternalism doesn't appeal to the "care" receptor; left libertarianism is a harsh philosophy to the extent that it tells people to get on with their own lives.

- Left-libertarianism is an anti-authoritarian belief, as it it denies that the state has the competence or authority to do very much. This turns off the authority receptor.

In these ways, left-libertarianism is, to use Haidt's metaphor, like a restaurant which serves only sweeteners. It appeals to only a fraction of people's palates.

Now, I don't think this is a good argument against left-libertarian ideas. Liberty and equality are good receptors, and there's plenty to be said for the economic efficiency too. And anyway, there's no logical reason why the state must appeal to all our tastebuds. If you have a taste for loyalty, authority or sanctity, you can find them elsewhere in a free society. As Nozick said, a libertarian state is a framework in which you can pursue your own utopia.

All I'm saying is that there are massive obstacles to left-libertarianism becoming popular. But let's remember that what's popular is not necessarily what's right.

September 13, 2012

Trusting authority

In a discussion with Jonathan Sacks, Richard Dawkins reads a letter he wrote to his daughter asking her to think for herself:

Next time somebody tells you something that sounds important, think to yourself: ‘Is this the kind of thing that people probably know because of evidence? Or is it the kind of thing that people only believe because of tradition, authority or revelation?'

This has always struck me as bad advice, even to an adult.Research into cognitive biases has surely strengthened the case for agreeing instead with Edmund Burke:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would be better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations, and of ages. (Reflections on the Revolution in France, par 145)

This is what we do every day. From putting the kettle on in the morning to taking the medicine the doctor prescribed to turning the light off at night we unthinkingly rely upon others' knowledge.As Alfred North Whitehead said, "Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them."

And many of our non-religious beliefs come not from our independent thinking but from authority. We believe in evolution and climate change not because we've gathered evidence ourselves or tested the evidence provided by others, but because it is the consensus of scientists.

So far, so good. But on the other hand, the Hillsborough report highlights why Dawkins might be right. I mean this in two ways:

- Irvine Patnick (pdf) and Kelvin Mackenzie both trusted lying policemen.

- Jack Straw now regrets that Lord Justice Stuart-Smith failed to expose the extent to which the police perverted the course of justice in covering up their murderous incompetence. He was guilty of trusting Stuart-Smith's authority too much, as Stuart-Smith trusted the police too much.

So, what is the difference between "good" reliance on authority and bad? In many cases, it's because empirical evidence justifies it. We trust that doctors will prescribe us the correct medicine because most of us have survived our encounters with the medical profession. But this consideration doesn't apply in one-shot questions.I'd suggest two criteria here:

1. Wishful thinking. If you trust an "expert" because you want to, you raise your odds of being wrong. Patnick and Mackenzie wanted reasons to hate working class Scousers so were happy to believe the lies. And Straw - who never saw a powerful arse he didn't want to kiss - wanted to believe that judges were diligent and competent.

2. Incentives. Coppers, I suspect, are no more innately corrupt than anyone else.But they had huge incentives to lie to hide their incompetence.And people respond to incentives.

I would amend Dawkins thus:

Think to yourself: ‘Is this the kind of thing that I want to believe? Are people telling me this because they have an incentive to do so? If the answers are yes, don't trust the authority, and look for the evidence.

September 12, 2012

The productivity puzzle

Labour productivity is falling. Today's figures show that total hours worked have risen 1.6% in the last year, whilst the NIESR estimates that GDP fell 0.2% in the time. GDP per hour is now 4.5% below 2007Q4's level. Had productivity continued to grow at its 1977-2007 rate, it would be 10.8% higher.

Now, some of the productivity shortfall reflects Q2's temporary Jubilee-induced drop in GDP. And maybe some of it is due to GDP being under-recorded and/or hours being over-recorded; there is, remember, considerable sampling error in the employment data.

But this cannot be the whole story. It cannot explain all of the 13.7% gap between where productivity is and where it would be, had past trend growth continued.

So, what can explain this? A strong candidate is labour hoarding (pdf); firms have been hanging onto workers in the hope (pdf) of an upturn in demand.

I don't deny that this is part of the story, maybe a large part. But three things make me doubt that it's the whole story.

1. Labour hoarding should be reversing now. Between 2007Q4 (the cyclical peak) and 2009Q3, GDP fell 7% whilst hours worked fell 3%. This tells us there was considerable labour hoarding in the early stage of the crisis.In a normal recession/recovery, this process would be unwinding now, as some firms enjoy rising production whilst others give up hope and cut staff. But it isn't happening. Since 2009Q3, GDP has grown 2.4% whilst hours have risen 2.8%.

2. Companies in aggregate want to pay off debt or raise cash. Why then should they be unusually keen to jeopardise cashflow by retaining staff?

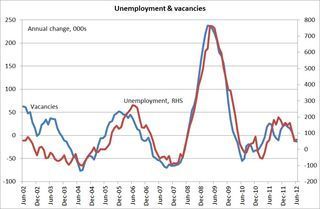

3. If we were seeing labour hoarding in a weak economy, there should be a drop in the job separation rate and therefore a low level of unemployment, given the level of vacancies. But this doesn't seem to be happening. In the last 12 months, the change in unemployment has been pretty much what you'd expect, given the small rise in vacancies.

These doubts make me fear that something else is at work - that maybe there is a genuine productivity slowdown. Two things lend credence to this:

- One effect of the financial crisis is to starve new firms of the finance to expand. This retards the creative destruction which is key to productivity growth. A lot of this growth, remember, comes not from existing establishments increasing their efficiency, but from workplaces closing down and being replaced (pdf) by newer ones. Anything that slows this external restructuring is bad for productivity.

- Even before the crisis, firms were holding back on investment. This should lead to slower productivity growth. This is partly because it means workers are using less efficient capital; they spend their time cussing servers and printers rather than working. But it's also because a lack of investment is a symptom of pessimism about future growth - a pessimism which seems to be correct.

Now, I don't say this to dismiss labour hoarding or mismeasurement as possible explanations. All I'm saying is that the productivity puzzle is a deep one. And I'm not sure it has a happy solution.

September 11, 2012

The machismo paradox

Emma Burnell's complaint that politics is "becoming increasingly macho" seems widely shared. There's disquiet over how the Cabinet reshuffle further reduced women's role in government. And Rachel Sylvester in the Times today bemoans how Cameron "has gone all 'calm down dear' butch."

We need some historical perspective here. Politics has long been a masculine affair. Back in the early 80s, David Owen - then leader of the SDP - tried to present a macho image, prompting Michael Foot to quote Mae West: "men who try to act macho aren't very mucho."

Nevertheless, Emma's point raises a paradox. It starts with evidence from at least two different arenas shows that masculinity can be a handicap:

- Among equity investors and analysts, women (or at least people who conform to traditional feminine sterotypes) seem to do better than men. This could be because men are more overconfident and risk-seeking.

- Firms with more women directors perform better than others.

Granted, this evidence is not wholly overwhelming (pdf). But it's directly relevant to politics. Equity investing and corporate strategy are like policy-making, in that all require people to make judgments under uncertainty.It might be no accident, therefore, that there's also evidence that countries with more female MPs tend to have faster economic growth than others.

And here's the paradox. Although the empirical evidence seems to undermine the case for machismo in politics - or at least, it doesn't obviously support it - there seems to have been no decline in such machismo. Politics is still dominated by the silly masculine traits of certainty and overconfidence.

Why? Here's a theory. What people (or the media?) want from politicians is not an ability to take decisions, which requires the recognition of uncertainty.Instead, they want is a false sense of certainty, a "strong leader" with a "clear" direction. And this demand favours macho politicians, even if they are poor decision-makers.

September 10, 2012

Conservatives - support unions!

Trades union membership has fallen to its lowest level since the 1940s. In principle, this should trouble conservatives.

This is because trade unions are an example of non-statist self-reliance, of people organizing to help themselves rather than looking to government.

I say this because of a fact pointed out by Philippe Aghion and colleagues - that there is a strong negative correlation across countries between union membership and minimum wage laws. Countries with strong unions, such as the Nordic nations, tend to have no minimum wage laws whilst countries with lower union membership, such as Greece or France, have stronger minimum wage legislation.

The UK had no national minimum wage in the 50s and 60s, believing that collective bargaining could better regulate wages. It was only after the collapse in union power that a NMW was enacted.

I suspect that what's true of minimum wages might also be true of other aspects of regulation. Elf n safety laws also increased after the decline of unions.

Unions, then, are an alternative to state intervention.There's a simple reason for this. Workers, naturally, will always want their working standards improved. If they cannot pursue this aim through unionization, they'll do so through politics instead.

But the thing is that collective bargaining is a more efficient way of protecting workers than the law.One reason for this is that the law inflexibly applies to everyone, whereas bargaining allows for workers to accept worse wages or working conditions where it would be prohibitively expensive to improve them. Also, the complexity of the law creates uncertainty which can be worse for business than good working relations with a union.

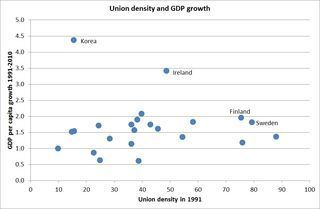

These considerations lead me to this chart. Drawn from the OECD and other sources, it plots union density in 1991 (admittedly an arbitrary date) against GDP growth since then. You can see that there is only a negative correlation between the two because of that Korean outlier.If Korea is excluded, there is a positive correlation (0.25) across the 22 advanced nations in my sample between union density and subsequent growth.Highly unionized Finland and Sweden have done better than less unionized Japan or the US.

This isn't so robust as to suggest that unions are definitely good for growth. But it does mean they aren't obviously bad*.

In this sense, people who want less state intervention and stronger growth should be sympathetic towards unions. So, why aren't Tories mourning their decline? I mean, it's not as if they just blindly hate the working class, is it?

* There is a strong negative correlation between the change in union density and GDP growth over this time; faster-growing economies have seen bigger falls in union density. But there's an endogeneity issue here. It could be that fast growth is associated with more creative destruction, which sees the decline of unionised workplaces and emergence of more non-unionised ones, whereas a sclerotic economy preserves unionized workplaces.

September 9, 2012

Predistribution, human capital & equality

Is Ed Miliband stuck in a 1990s timewarp? I ask because his idea that predistribution entails "a much higher skill, higher wage economy" seems too wedded to New Labour's excessive emphasis upon human capital as a force for inequality.

I mean this in separate ways.

First, take inequality at the top of the income distribution.90/10 inequality - the gap between the poorest 10% and the richest 10% - might be amenable to upskilling, in the sense that increasing the supply of skilled workers should reduce the price of them.This was New Labour's thinking in the 90s.

But today, I suspect that most people are worried not so much by the income of the 90th percentile - someone on just over £50,000pa - but those of the top 1%. And this inequality is unlikely to be reduced by human capital policies. At best, the hyper-rich owe their high incomes to winner-take-all effects (pdf) and marginal differences in skill - of the sort that can't be imparted by education. At worst, they are due to the use of power to extract rents from workers, shareholders or the state.

The answer to such inequality is not to increase skills.It's to empower shareholders or, better still workers, to restrain CEO pay, and to reform banking seriously. Aside from talk of "responsible capitalism" and "banks that serve the country", Miliband offered little hint of this.

Secondly, I'm not convinced by Miliband's thinking about the lower paid. He says:

Think about somebody working in a call centre, a supermarket, or in an old peoples’ home.

Redistribution offers a top-up to their wages.

Predistribution seeks to offer them more:

Higher skills.

With higher wages.

Isn't this the fallacy of composition? Sure, if a single supermarket worker has high skills, she might well be able to move up a career ladder and get out of poverty. But if everyone has high skills, there'll just be more people stuck in jobs for which they are overqualified. If wages and productivity are attached to jobs rather than people, mass upskilling isn't the route out of poverty.

Of course, one might argue that employers would respond to the higher supply of skills by creating jobs with higher skill requirements and wages. But there's little evidence that this anti-Bravermanian process is happening, and there are good reasons to think it won't.

I don't say all this to deny that a more skilled workforce might be good for growth - that's a different story (pdf). It's just that, as a force for reducing inequality it is, surely, limited. Shouldn't we have learned this since the 1990s?

September 7, 2012

History & wealth: Burke vs Rand

Via the CEPR come two new papers:

Almost (pdf) a century and a half after the first large [United States] migration wave of the late 19th century, those places where migrants settled in big numbers are significantly better off than those which were virtually untouched by the migration wave...migration has left an imprint which still affects economic performance.

And a study (pdf) of 18th and 19th century England finds that:

children of couples of low fecundity (and hence small families) were more likely to become literate and employed in a skilled profession than those born to couples of high fecundity.

This, the authors say "could well have played a key role" in the industrial revolution.

These two different papers add to a growing body of evidence which shows that quite distant history strongly influences our economic fortunes today. Barack Obama was right to say in his "you didn't build that" speech that "if you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own." You were helped not only by teachers and the government, but (unwittingly?) by previous generations.

In those remarks, Obama was criticizing Randian Conservatives - who are sadly not confined to the US - with their silly idea that today's rich are heroic self-made men. But there is another strand of conservatism which is wholly consistent with the idea that we owe our fortune to the past. Edmund Burke famously said that society is "a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born."

Which raises a paradox. Whilst economic research now supports Burke's view, much of the right no longer does so, preferring ahistorical inidividualist tosh. But as Will says:

A Conservative without a sense of history is just a whining, pleading bully.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers