Chris Dillow's Blog, page 172

August 13, 2012

Why teach sport?

Cameron and Johnson want there to be more competitive sport in state schools. Why?

The natural answer is simply that they're hopping onto a bandwagon. They've discovered that sport is popular, and want now to be associated with it - notwithstanding that they cut the schools sports partnership only a few months ago.

There are other possibilities. One, pointed out by Shuggy, is that a sporting career is a suitable ambition for the lower orders to have.

I want to suggest another motive. It starts from the fact that there is evidence that children who play sport go on to earn more than those who don't.

Now, you might think this is a knock-down argument for teaching sport. It inculcates non-cognitive skills such as teamwork, discipline and the pursuit of excellence that help people get ahead in later life.

Maybe. But this poses a question: why assume that we need competitive sport to promote these values? The phenomenon of counter-education means many people are turned against sport, and the good values associated with it, by being compelled to do it in schools. For such people, discipline and teamwork might be better instilled by encouraging non-sporty types to join choirs, bands or dance troupes.

Why, then, want sport to be taught in schools whilst sneering at Indian dancing?

The answer, I think, lies in a paper (pdf) by Jeremy Celse.He points out that sport doesn't just promote virtues. It also promotes the vice of envy. It encourages people to become more cut-throat and more willing to hurt others to get ahead.The sporting mentality, remember, gives us Kevin Pietersen and John Terry as well as Mo Farah.

And herein, I think, lies Cameron and Johnson's enthusiasm for teaching competitive sport. They want schools to produce the right sort of chap - people like themselves.And this requires that they churn out ruthless competitive egotists.

August 12, 2012

Why we disagree

Laurie Penny recently tweeted that it's easy to write young Tories off as "loathsome" without asking: why do humans behave like this?

Of course, some people on the right are loathsome racist sociopaths and snobs. But some are not, whilst some lefties are arrogant sanctimonious prigs. And tribalism, groupthink and the confirmation bias combine to increase both sides' fanaticism*.

I suspect that one under-rated reason for disagreement lies not just in differences in values or frames or in class interests, but rather in question of fact. For example:

- Is success in life due more to hard work and graft, or to luck?

- Are successful businessmen entrepreneurs who benefit society or rent-seeking exploiters?

- Is the state a force for oppression, or a means of enabling people to pursue their dreams by providing a welfare state, education and sports funding?

- Is market failure a greater problem than government failure?

- Is freedom restricted merely by the state, or by employers, in which case state intervention might be liberating?

- To what extent is state intervention rendered ineffective or counterproductive by problems of bounded rationality and limited knowledge?

These are, of course, all matters of degree. The difference between left and right is where they place the emphasis; I'd add (of course!) that the answers can be blurred by cognitive biases.

But here's the thing. We tend to think of empirical questions as ones that can be decided by evidence - as distinct from questions of values which are intractable. However, these empirical questions are, I suspect, intractable, simply because society and the economy are too complex to admit of simple answers. The fact-value distinction might not be as sharp as we think.

* Sometimes, (wilful) misunderstanding exacerbates the conflict.For example, it really irritates me when right libertarians equate "capitalism" with "free markets." And it's easy to read our opponents in the meanest and most exacting way possible, whilst giving our own side an easier ride.

August 10, 2012

The anti-capitalist Olympics

It's sometimes said that sport is a mirror of society. Watching the Olympics, though, makes me think the opposite is the case, as Olympians represent values which are disappearing from society.

I'm thinking of Macintyre's distinction between external goods (such as power, wealth and fame) versus the internal good of excellence at a particular practice. Olympians pursue the latter. Yes, money and fame can follow from gold medals, but only as a by-product. There are surely countless easier ways for Anna Watkins to get rich than by getting up at stupid o'clock to torture herself.

In this sense, though, Olympians are rare, because most other people pursue the external goods of money, power and fame. And, what's more, capitalism - or maybe just any market economy - prioritises external goods over internal ones. I mean this in four senses:

1. Incentives. Capitalist incentives can crowd out excellence. The excellent banker who judges risk well can be sacked in the pursuit of short-term profit.The excellent middle manager who has maximized profits will find it harder to achieve a target of raising profits further than the mediocre manager who presides over inefficiency. And promotion often depends upon managers resembling their bosses than upon them being genuinely good. It's this incentive issue that answers Will's question of why British managers are so good at managing (some) sports but so bad at managing business.

2. Culture. From a capitalist point of view, Anna Watkins is a disaster; it would be much better for the economy if she stopped larking around in boats and got a well-paid job and spent all her money on shoes. The truly excellent cleaner or driver gets none of the wealth or power of the most mediocre CEO. And the people who reject career paths are regarded as eccentrics if not scroungers.Capitalism wants, and promotes, consumerism and greed rather than excellence.

3. Power. Capitalists often don't want excellent workers, as these are hard to control and have market power. For these reasons, as Richard Sennett and Harry Braverman showed, capitalists deskill the labour process by taking excellence out of the workplace.

4. Consumerism. The notion of excellence, said Macintyre, is (largely) objective. In a market economy, however, "the customer is king." And the customer is often a poor judge.In music, histrionic screeching sells better than subtle good phrasing. In TV, great shows often get pathetic audiences. And writers of "no redeeming literary merit at all" can sell millions.

Macintyre, however, went on to make a distinction between the two:

External goods are...characteristically objects of competition in which there must be losers as well as winners. Internal goods are indeed the outcome of competition to excel, but it is characteristic of them that their achievement is a good for the whole community. (After Virtue p 190-1).

This is surely (often?) true: Usain Bolt's achievements enrich us, Whereas bankers' wealth impoverishes us. As Frances says, there's a "broken link" between work that helps society and individual remuneration.

In an important sense, then, Olympic participants (as distinct from their organizers!) represent something that's being squeezed out of wider society - the pursuit of internal rather than external goods. In this sense, the games are anti-capitalist.

August 1, 2012

Gender & ethical compromises

Michael Sandel's new book, What Money Can't Buy, has revived interest in Michael Walzer's idea of "blocked exchanges" - that there should be limits on what can be exchanged for. What sort of people are most likely to support such ideas?

Women, that's who, according to research (pdf) by Jessica Kenneby and Laura Kray at the University of California, Berkeley.

They got students to read stories of how people had sacrificed ethics in the pursuit of cash, for example by selling products they knew to be dangerous. And they found that women were more likely to express moral outrage at such episodes.Women, they conclude, are more reluctant to trade off moral values against making money.This is consistent with other research (pdf) by Ms Kray which has found that "men are more pragmatic in their ethical reasoning at the bargaining table than women."

Whether such differences reflect natural differences or differences in the way we are socialized is a seperate question.

Kenneby and Kray say this might help explain why women are under-represented in boardrooms:

Women's ethical standards may disadvantage them relative to men as they seek advancement in business.

Does it follow that companies would behave more ethically if they had more women in positions of influence?

I'm not sure. The differences Kray and Kenneby identify are, of course, only differences on average. Lots of women are an exception to this average and have more, ahem, pragmatic ethical standards than men; Sandel and Walzer are blokes, remember. And it's reasonable to suppose that they - more than average women - will select into occupations requiring ethical compromises. If businesses try to promote more women, they are likely to promote these women, rather than pluck random ones off the street. If so, then more females in boardrooms won't necessarily mean greater ethical standards. There's a difference between being a woman and acting like a woman.

July 31, 2012

Why Romney's right

If I promise not to make a habit of it, can I defend Mitt Romney? Although his remarks in "the capital of Israel" have caused derision, there's one point he makes that deserves respect. This is that "culture makes all the difference" to a nation's prosperity.

Leave aside the empirical evidence he provides; Israel and Palestine are only two data points with many confounding factors. This point is true (allowing for overstatement) and important. For example:

- A culture of trust and trustworthiness can promote growth by overcoming problems of asymmetric information and incomplete contracts.

- Deirdre McCloskey has argued that "bourgeois virtues" such as temperance, hope and prudence are good for an economy.

- Heng-fu Zou has shown how the "spirit of capitalism" - a desire for wealth in itself, independent of the consumption it gives - can help explain cross-country differences in growth rates. "It Is a mistake to totally ignore the cultural elements in economic growth and development" he says.

- Guido Tabellini has shown how nations and regions where people are more likely to respect each other tend (pdf) to grow faster.

- Gerard Roland and Yuriy Gorodnichenko have shown that "individualistic culture has a strong causal effect on economic development."

Culture, then, matters. But where does culture come from? Here, Romney scores another point - religion. Here's Luigi Zingales and colleagues (pdf):

On average, religious beliefs are associated with ‘‘good’’ economic attitudes, where ‘‘good’’ is defined as conducive to higher per capita income and growth...Christian religions are more positively associated with attitudes conducive to economic growth.

And here's (pdf) Robert Barro and Rachel McCleary:

We find that economic growth responds positively to the extent of religious beliefs, notably those in hell and heaven, but negatively to church attendance.

But of course, religion is not the only source of culture. Another source is history. Nations or regions with a history of slavery or genocide have tended to grow more slowly even in decades afterwards, because such episodes destroy trust or bourgeois virtues.

Now, Mitt Romney no doubt regards the vicissitudes of distant history not as accidents but as the "hand of providence". Unless there's some evidence I've overlooked, I suspect this is another example of the just world illusion.

I say all this because there are two large groups of people are who are prone to error here. On the one hand there are the (dwindling) number of economists who think that long-run growth is a matter of technocratic fixes, of establishing the right policies and institutions. On the other hand, there are politicians who think that culture can be changed by talk and wishful thinking. The truth is more interesting than either group realizes.

In this context, underneath the imbecilities, Romney has, perhaps inadvertently, blurted out something important.

July 30, 2012

Corporate crime: basic economics

Unlearning Economics says that capitalism gives us "institutionalized law-breaking":

Corporations have long history of force, fraud and theft...In a system based on private accumulation, they will use their profits to corrupt the legal system, hijack public funds, get the best lawyers, and make their operations as opaque as possible to avoid prosecution, no matter the charge. None of this is a bug of capitalism; it is a feature.

If this sounds like a lefty rant, it shouldn't. It's just elementary economics.

This tells us that firms supply things up to the point at which the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost. But this doesn't merely apply to the supply of goods and services. As Gary Becker showed (pdf) it also applies to crime. Companies (like individuals) will commit crime up to the point at which the benefit of doing so - higher profits - exceeds the cost. In the amoral world of econ 101, the cost is the penalty for being caught (criminal punishment plus loss of business from irate customers), multiplied by the probability of being caught*.

We should, then, expect there to be a positive level of corporate crime and bad behaviour: fraud, money-laundering, breach of health and safety laws, the silencing of critics and so on.

However, it's not just companies for whom the optimum level of crime is positive. The same is true for society as a whole, because the cost of detecting and prosecuting some crimes might exceed the social cost of their commission; there is a reason why the government doesn't employ the whole population as policemen. As David Friedman wrote:

Theft is inefficient—but spending a hundred dollars to prevent a ten-dollar theft is still more inefficient. Reducing theft to zero would almost certainly cost more than it would be worth. What we want, from the standpoint of economic efficiency, is the optimal level of theft. We want to increase our expenditures on law enforcement only as long as one more dollar spent catching and punishing thieves reduces the net cost of theft by more than a dollar. Beyond that point, additional reductions in theft cost more than they are worth.

But here's the thing. The relative cost of investigating corporate crime is very often high; 90 officers are employed by Operation Weeting, for example.If Stephen Green didn't know about HSBC's dealings with money launderers, what chance would the average plod have of finding out?

Given these costs**, we'd expect scarce policing resources to be directed towards lower cost activities such as arresting cyclists.

We would therefore expect companies to commit crime and the state to tolerate this, up to a point. You don't have to be a leftist to see this. You just need to know very basic economics.

* In a world where morality matters, we can add to the cost term a "psychic cost" of the sense of shame and guilt of doing bad things. But there's no reason, a priori, to assume that this psychic cost is so high as to prevent all crime.

** One caveat here is that public outrage about corporate crime might increase the benefits to the state of devoting more resource to its detection. But efficiency requires that such resources be sufficient to placate public anger, not that they be sufficient to prevent all crime.

July 29, 2012

Freedom, well-being & capitalism

The ONS's effort to measure well-being has produced a backlash. In the Times, Phillip Collins says, to Norm's approval, that "it matters more that a life be freely chosen than that it should be happy." And the Spectator says:

The duty of government in a sane democracy is to protect our freedoms, which include the freedom to be unhappy if we wish. Studies of general contentment are for totalitarian regimes.

This conflict between freedom and happiness is not merely a philosophical one. Research shows it to be a hard empirical fact, in several ways:

- One paper finds that, controlling for other things, "economic freedom is significantly negatively related to life satisfaction."

- Evidence from the US (pdf) and around the world has found that improvements in women's real freedom has been associated with declines in their happiness.

- Barry Schwartz and Sheena Iyengar have argued that more choice (pdf) can lead to frustration and anxiety (pdf).

- Christopher Hsee has described (pdf) how we often choose things that are bad for us; rightists such as Bryan Caplan and Theodore Dalrymple contend that this is especially true for the poor.

But here's the question. Is this trade-off between happiness and freedom an ineradicable fact about human nature, or is it an artefact of a particular social structure?

Two things make me suggest that, to some extent, it's the latter.

First, Paolo Verme shows that the relationship between freedom and happiness depends upon our locus of control. If we have an internal locus - if we feel we are in comtrol of our own lives - then freedom does make us happy. If, however, we have an external locus - we think our fate depends upon fortune or upon others - then freedom doesn't make us happy.

This might help explain why older people in post-communist countries have been especially unhappy (pdf). They were brought up (by indoctrination and experience) to have an external locus of control. They thus saw increased freedom after the collapse of communism as a disconcerting threat.

And here's the thing. Hierarchical managerialist capitalism requires that lots of people have an external locus of control - that they do as they're told; the person who tries to take control of their own life will soon be sacked from the call centre or assembly line.And schools subtly indoctrinate people into this mindset. Capitalism thus requires, and produces, many people for whom there is, psychologically, a conflict between happiness and freedom.

Secondly, remember how surveyors ask about happiness. They don't ask: "are you having fun?". Instead they ask several questions (pdf), two of which are: "Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?" and "Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?" I strongly suspect that people who pursue professional or sporting excellence or who fight injustice - to use Norm and Phillip's examples - would give high scores on these questions: Norm and Phillip give no evidence to the contrary.

But how can I reconcile this suspicion with the evidence I've cited for a conflict between freedom and happiness? Simple. There's a conflict when people use freedom to choose what Edward Skidelsky calls "baubles and gadgets" or what MacIntyre calls external goods such as money, but not so much when they choose to pursue "internal goods" such as excellence.But capitalism requires that people pursue the former.

So, here's my theory. There's a conflict between freedom and happiness for capitalist people - consumers who do as they are told at work - but not for (market) socialist people, who are empowered to take control of their own lives.

Institutions shape culture. And capitalist institution give us a culture in which freedom and happiness conflict.

July 27, 2012

Cable's terrible excuse

There's one response to this week's poor GDP figures that hasn't had the criticism it deserves. It's this from Vince Cable (5'37" in for the Flanders-phobics):

No one was expecting that the situation across the channel would deteriorate as much as it has done...Everybody concerned under-estimated the enormous damage that had been done to this country as a result of the collapse of the financial system.

As statements of fact, these are reasonable, but as a defence of tight fiscal policy, they stink.

I say this because any sensible future-oriented plan - fiscal policy, business investment, household financial plans, whatever - must ask: would this plan be sensible if things turn out different from expectations? Is it resilient to shocks?

The fundamental fact about the future is that it is unknowable. Any policy which does not start from this premise is stupid.

If a man loses all his money at the roulette table and says "I didn't expect red to turn up" we don't sympathize with him. Likewise, it's no excuse that the euro crisis worsened. A plan that works only if everything turns out well is not really a plan at all.

Of course, the government could not have foreseen the worsening of the euro crisis. But it could, and should, have asked: if the economy is hit by an adverse demand shock, would fiscal tightening make sense?

At risk of sounding like a Monday morning quarterback* the answer to this question is surely: no.

This is not just because such a shock would increase the case against tight fiscal policy. It's because a world of weak growth is one in which investors want to hold government bonds, and thus is a world in which the cause for austerity - to avert a sell-off in gilts - diminishes.

Conversely, sensible policy-making would also have asked: would fiscal austerity be a good idea if we get a positive demand shock? The answer to this would not necessarily be: "yes". Granted, such a shock would see gilt yields rise simply as investors switch into riskier assets. But the sell-off would be mitigated by the fact that unanticipated growth would reduce the deficit more quickly than anticipated. And such a shock would also allow the government to change plan and tighten by more.

These considerations suggest that a sensible fiscal policy would not have been as tight as the one we have. What I'm saying here is just an expression of the Brainard principle - that uncertain policy-makers should tread cautiously.

In this context, Cable's words (if they are sincere, which I doubt) should be shocking. They suggest that the coalition did not undertake basic contigency thinking - that, as Hopi says, policy was based upon hubris and overconfidence.

* Some American sporting metaphors are good. My favourite is Barry Switzer's "Some people are born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple." Which is also relevant in this context.

July 26, 2012

Beyond models

Simon Wren-Lewis asks heterodox economists a question: how do you answer the question "what do consumers do if they are told that taxes are rising temporarily?" without some appeal to representative agents?

My answer is: I would start from a representative agent model (which predicts consumption smoothing) but I wouldn't stop there. On this issue, as on most other macro ones, I'd ask two further questions.

One is: do we have any reason to suspect that the representative agent perspective might be wrong? For example, some households might not have savings to run down in response to a tax rise, and might be unable to borrow; this is true for a minority (pdf).These people might be forced to cut spending.In this sense, heterogeneity matters, because models in which everyone is credit-constrained or nobody is are both wrong.

Heterogeneity also matters for firms. Geroski and Gregg's study of the 1990s recession found that most of the fall in output and employment was concentrated in a minority of firms, and Xavier Gabaix has shown how a few large firms can generate productivity fluctuations.Real business cycle theorists should make more of this.

The second question is: are there any cognitive biases which bear upon this issue?

For example, if consumption is determined by habits then agents' desire to smooth spending might (or not!) be even stronger than the conventional representative agent model predicts. But if agents have limited attention and so don't listen to the message that the tax rise is temporary (or don't believe it), then spending might fall by more.

Of course, models with both heterogenous agents and cognitive biases very quickly become fiendishly complex*. But then the economy is complex and as Wittgenstein said, a clear picture of a fuzzy thing is itself fuzzy.

But in the realm of policy advice, do we need to build such models? Isn't it better to be roughly right than precisely and elegantly wrong? As Stephane has complained, perhaps there's a cost to formal modelling - it can distract us from other ways of thinking about the economy.Worse still, in the wrong hands (which are not Simon's), it can distract us from the facts.

* I suspect one way forward is the use of agent-based computational models; this sort of thing might be the future of economics.

July 25, 2012

Producitivty growth: the long-term

If today's GDP figures are to be believed - which is a big if - productivity has slumped. The ONS says GDP fell 0.3% in the last two years whilst total hours worked rose 2.2%. This implies a drop in GDP per hour of 2.4%. What's more, productivity is 3.3% lower than it was five years ago.

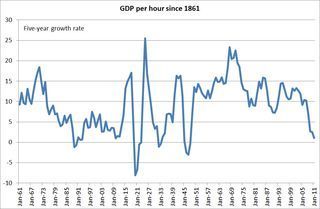

My chart, taken from the Bank of England's database*, puts this into historic context. It shows that, unless productivity recovers significantly in the rest of this year (which is possible), we'll see the first fall in peacetime five-year productivity since 1932, and only the second such drop since the late 1880s.

Now, I'm prepared to believe that productivity isn't really this bad: maybe GDP has been under-recorded and employment over-recorded; there's a lot of noise in the latter.

However, it's unlikely that data revisions will overturn the big message of my chart - that productivity growth has been trending downwards since the late 60s. As Noah Smith says, something big happened in the 70s.

To some extent, this something is simple mean reversion. If we split annual peacetime productivity growth into distinct periods we get:

1856-1913 = 1.3%

1920-1939 = 1.7%

1947-1973 = 3.1%

1973-2011 = 1.9%

What stands out here is the fast productivity growth during post-war period. The last 40 years of weaker growth look normal compared to the pre-war period.

This poses the question: why did productivity grow so well in the golden age?

Part of the story is that post-war reconstruction permitted a productivity catch-up. The new equipment firms bought after the war embodied the technological gains made in earlier years, but these gains natually eventually slowed down; Verdoorn's law predicts that rapid growth for any reason (eg growth of our export markets) will be associated with rapid productivity growth; and low commodity prices helped spur productivity too.

On this view, the golden age was a happy period which simply cannot be reattained.

This is undoubtedly part of the story. But is it the whole story?What if social democracy itself contributed to that productivity growth, for example:

- The belief that Keynesian policies would ensure full employment, along with a framework of statist planning, gave firms the confidence to invest, and better capital equimpment means more productive workers.

- Full employment and strong trades unions meant that managers could not make big profits merely by depressing wages, and so had to look for genuine efficiency gains.

- Workplaces in which managers consult with unions, and so gain cooperation, find it easier to grow productivity than dictatorial workplaces;industrial relations weren't entirely conflictual in the 60s, remember.

What lends this view some credence is the sluggish productivity growth of the pre-1914 period. This suggests that free markets on their own do not unleash rapid productivity improvements.

If this line of thinking is anywhere near-correct, then a serious recovery in productivity requires big political change.

* I'm measuring labour input by average weekly hours multiplied by employment. Note that the working week has almost halved since the 1850s, from almost 60 hours to just over 31.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers