Chris Dillow's Blog, page 171

August 24, 2012

QE & inequality: don't blame the Bank

The Bank of England's admission that QE disproportionately benefited the rich has attracted some criticism. This is mistaken. The Bank has done nothing wrong.

The finding that QE increased inequality is a statement of the bleeding obvious. QE has raised asset prices, and it is only the rich who have financial assets; the Bank estimates that the median household has gross financial wealth of only £1500. As Ben says, it is therefore no surprise that QE has increased inequality.

But this is not the Bank's fault. If financial wealth had been equally spread - which is a fantasy of representative agent economics more than of socialists - then everyone would have gained from QE. QE's regressive impact thus reflects the pre-existing inequality of wealth, and the Bank can't be much blamed for that*.

And the fact that the rich have benefited most from QE does not mean that others haven't benefited. People without financial assets have gained, to the (small) extent that QE has increased job security and raised inflation, thus eroding the value of debt.

There is, though, another reason to defend the Bank. In considering the impact upon inequality, what matters is the entire set of policies, not any single one.

Take a different example. Taxes such as VAT or excise duties are regressive. But we have them because they are (relatively) efficient, and we offset their regressiveness by having other progressive tax and benefit policies.

The same thing should be true of QE. If this is an effective way of supporting the economy then it should be implemented, regardless of its distributional impact. And if you don't like that distributional impact, the solution is to mitigate it through the tax and benefit system. That way, we get the benefit of QE but neutralize its unpleasant distributional effects - subject to caveats about the deadweight cost of taxes.

Rather than blame the Bank, we should blame governments - both Labour and Tory - in three ways.

1. If they had undertaken more counter-cyclical fiscal policy (which is perhaps less inegalitarian anyway than QE) there'd be less need for QE. QE is a second-best alternative (if that!) to sensible fiscal policy.

2.If wealth inequality were not so high in the first place, QE would not be so inegalitarian. In this sense, QE's adverse side-effect reflects a failure of the New Labour government.

3. The government's failure to use the tax system to neutralize QE's inegalitarianism represents a tolerance of greater inequality.

By all means, criticize the effectiveness of QE; I'll have some sympathy. But its impact upon inequality is not an argument against QE. And the Bank shouldn't be blamed for that rising inequality.

* The qualifier matters. US evidence (pdf) suggests that ordinary monetary policy has large distributional effects.

August 23, 2012

"Nothing to fear"?

Here's the latest Tory idiocy. Dominic Raab says the "talented and hard-working have nothing to fear" from a scrapping of "excessive protections" for workers.

Let's ignore the fact that the UK has some of the weakest job protection laws in the world. Let's also ignore the fact that there's no evidence that scrapping employment protection would create new jobs. And let's also ignore the fact that employment protection is of only marginal concern to small businesses, and that even a former director-general of the CBI has mocked the idea of abolishing the few protections workers have.

Is Raab right that the best workers have nothing to fear?

No.It's easy to think of many ways in which talented and hard-working people might reasonably fear the sack. A middle-manager ordered to cut costs might prefer to sack better-paid workers. A soft-hearted one might prefer to sack the talented in the belief that they can more easily find work elsewhere. Or he might simply not be able to recognize talent, if it's outside his field; engineers can be bad at spotting financial ability, and vice versa. Or he might simply regard a good worker as a threat to his own position - possibly reasonably so, given that talented people have market power and so are hard to make profits from.

We know from the US - one of the few countries in the world with less job protection than the UK - that bosses can be petty tyrants who sack workers on flimsy pretexts.

Now, you might reply that if Raab is taking too optimistic a view of managers' decency and ability, I'm taking too pessimistic a one. But the point of laws is to protect us from the minority of wrong-doers. The vast majority of people are not thieves or murders - but this fact doesn't negate the need for laws against theft and murder. As James Madison said, "If men were angels, no government would be necessary." But some are not angels.

I'm pretty sure, then, that Raab is talking rot. What I'm not so sure about is why. One possibility is that he's so blinded by free market ideology and by romantic ideas about entrepreneurs and managers that he just cannot see that some free market reforms are of negligible benefit and that some bosses are less than heroic.

But you'd have thought that the experience of the crisis - which has seen bankers get multi-million bonuses whilst good workers lose their jobs - would have disabused anyone of the just world theory that capitalism rewards talent and effort. There's comes a point when a cognitive bias shades into a psychiatric disorder.

This leaves another possibility. It's that Raab is simply taking sides in a class war. He wants to further empower bosses to bully workers, even if this has no macroeconomic benefit.

August 22, 2012

Rape & self-ownership: a paradox

In all the talk about rape, there's an overlooked irony. It's about our attitudes to the concept of self-ownership.

Consider the position that rape is rape - that there are no meaningful distinctions between "legitimate" or "serious" rape or "bad sexual etiquette" - and that all rape is absolutely wrong. What could be the philosophical basis for such a view?

The obvious candidate is the idea of self-ownership. This says that women own their own bodies and should therefore have control over them. Any unsolicited "insertion" is therefore absolutely wrong because it's a violation of the right of self-ownership.

Now, I'm no expert, but I suspect this idea represents a big strand of feminism - from the publication of Our Bodies Ourselves in 1971 to women's efforts to get birth control, the demand to "stay out of my uterus" and Laurie's affirmation of "agency and self-determination, the right to own our own desire."

And this is where the irony enters. This right to self-ownership is typically associated with classical liberals and libertarians. It was John Locke who said: "Every man has a property in his own person: this no body has any right to but himself." And Robert Nozick's libertarianism has been described as a theory of self-ownership. Such self-ownership is often the basis of the claim that taxation is akin to theft or forced labour.

We'd expect, therefore, that feminists and classical liberals would have common cause. Both, after all, assert a right of self-ownership.

But this is not so. Very many feminists who assert women's rights to self-ownership, I suspect, reject right libertarianism, whilst it is rightists and classical liberals who are often most keen to look for gradations of rape, which rejects women's absolute self-ownership.

This, I suspect, helps explain Cath's disappointment with leftist men who try to excuse rape. Many on the left reject the idea of self-ownership because of its right-libertarian connections. But once you stray from the self-ownership principle, you tend to undermine the absolute prohibition against any unwanted sexual acts.

Now, I don't think feminists are necessarily guilty of inconsistency here. It's perfectly possible to assert some form of right of self-ownership and yet support egalitarian economic policies, as Jerry Cohen and Michael Otsuka have shown.

What I'm not so sure about is the position of those rightists who want to reject the "rape is rape" line. How can you equivocate about a woman's self-ownership of her body when she is confronted by a sexual predator, and yet assert her right of self-ownership when she is confronted by the taxman? It can't be that the right care more about the interests of rich men than about intellectual consistency, can it?

There is, though, one man here who is entirely consistent - George Galloway. His claim that Assange's actions were "not rape" is consistent with his support for dictators, in that both represent a denial of even the weakest rights of individuals' self-ownership. Our admiration for his consistency should, however, be tempered by the fact that he is consistently a twat.

August 21, 2012

Austerity's not working

Yet again, government borrowing has exceeded expectations. So far this financial year, the deficit on current borrowing* has been £42.1bn compared to £30.9bn in the same period last year. This puts in doubt the OBR's forecast that this deficit would fall this year, from £98.9bn to £95.3bn.

Duncan says this shows how austerity is self-defeating; a squeeze on spending weakens growth and thus reduces tax revenue.

I'd add that this will remain the case for as long as the private sector deleverages. This is because of a simple, basic, unavoidable identity - that for every borrower there must be a lender. Government borrowing - by definition - means that other sectors are net savers.

The problem is that there are only three other sectors, and all three have reasons to want to save or pay down debt:

- Households. Low consumer confidence means these are loath to borrow. And it might be the case that - with the debt-income ratio still high - they will continue to deleverage.

- Foreigners. The desire of Asian economies to save heavily is unlikely to cease soon. And the credit squeeze in the euro area is creating forced savers.

- Companies. Spare capacity, a dearth of investment opportunities and depressed confidence (partly thanks to the euro crisis) are all holding back investment, and encouraging firms to build up cash piles and pay off debt.Today's CBI survey found a fall in order books, consistent with a continued reluctance to invest.

Now, as long as these three sectors want to save, the government will have to borrow, simply as an accounting identity. The mechanism through which this happens is, of course, that higher private savings mean weak activity, which means weak tax revenues and higher welfare payments.

There are three implications here.

1. Government borrowing will fall when and only when the private sector saves less. The government is not in control of the public finances. Austerity works as a deficit reduction policy only insofar as it encourages the private sector to save less. Whilst this might happen sometimes - if tighter fiscal policy encourages borrowing by lowering interest rates or increasing business confidence - these mechanisms are weak here and now.

2. The only deficit reduction strategies that make any sense at all are those which aim at reducing private sector net saving. The Funding for Lending Scheme, aimed at encouraging borrowing, is the right kind of idea, though I doubt how practically effective it'll be.

3. An overshoot in government borrowing will not greatly raise gilt yields; although gilt prices fell today they are extraordinarily high by historic standards. This is because the same private sector savings that cause the government to borrow also create a favourable climate for gilts - namely a weak economy that causes investors to favour safer assets, and a pool of cash from which to buy assets.

* I mention this measure as it is unaffected by the transfer of the Royal Mail pension plan.

August 20, 2012

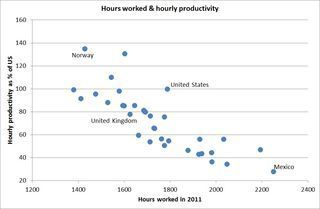

Laziness & productivity

Here are some Tories:

Once they enter the workplace, the British are among the worst idlers in the world...We work among the lowest hours, we retire early and our productivity is poor.

This is silly. We must not equate being idle in the sense of putting in few hours with being idle in the sense of having low productivity in those hours we do work. They are not just different things, but opposed things.

Let's look at the facts.UK workers do indeed put in fewer hours than most. OECD data show that the British worked an average of 1625 hours in 2011. That's less than the OECD average*.

But it's not the case that our productivity - in terms of output per hour - is poor.In fact, it's above the OECD average.

What's more, across the 35 countries in the OECD's sample, there's a strong negative correlation (-0.81) between hours worked and productivity.Nations with long working hours tend to have low productivity, and nations with shorter hours have higher productivity.

Of the 11 OECD countries with the longest working hours, all have lower productivity than the UK - in most cases very much so. Koreans, for example, work one-third longer than we do, but those hours are only 40% as productive.

By contrast, every single one of the nations with shorter hours than the UK has higher hourly productivity.

The US is an outlier by international standards in having both long working hours and high productivity.

There are good reasons for this strong inverse correlation:

- Poor countries tend to have low capital stocks. They therefore need higher labour inputs.

- Poor countries have less chance to specialise properly, because as Adam Smith said, the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market. This too reduces productivity.

- There are diminishing returns to labour. If you work long hours, you'll be unable to concentrate and so you'll be less able to fill the unfogiving minute with 60 seconds of distance run. Instead, you'll stop for breaks. There's a reason why "watercooler talk" is an American expression, not a Dutch one.

- Leisure is a normal good. As our incomes rise, our demand for it falls. You'd expect richer folk to work less, on average.

But what if we compare the UK to those nations with both higher hourly productivity and higher working hours than us: Sweden, the US, Finland, Spain, and Australia? Can we blame the UK's low productivity relative to these upon our laziness?

Not necessarily. There are countless other possibilities, such as bad planning laws, poor management (pdf), a lower capital stock (pdf), less product market competition, a worse cyclical downturn, and so on. Blaming lazy workers is, well, just lazy.

* Let's ignore the fact that this is due in part to a lack of demand; there were over one million people working part-time last year who wanted to work longer hours.

August 19, 2012

Obesity, imitation and equilibria

Judging by the cyclists on our roads and the new members at my gym, the Olympics has inspired Rutland's fattest women to take up exercise rather than the milfiest. If this is the case - and what could possibly be wrong with anecdotal evidence? - it raises an issue about the fragility of equilibria in networks.

You might think that cost-benefit thinking predicts that fatter folk would be more likely to take up exercise, because the benefits of moving from (say) a BMI of 30 to one of 25 are greater than those of going from 25 to 20 whilst the costs of doing so are smaller; the first few pounds fall off very easily.

Such thinking, however, fails to explain why folk get fat in the first place. One reason why they do, economists believe, lies in peer (pdf) effects. If our friends and neighbours are chubby, we are more likely to become so, because being surrounded by lardies increases our estimation of what represents a normal weight.

This is where the Olympics enters. Jess and Victoria have given women very salient role models. The comparator for body weight, for some people, has shifted from their fat friends to slimmer Olympians, which has inspired them to lose weight.

This is why I say equilibria are fragile. Our behaviour often imitates others. But which others? Changes in whom we imitiate can change behaviour very radically. Take just two examples:

- Riots. If one or two people follow the first person to cause trouble, a riot can spread - as subsequent people follow the group. But if they don't, the riot won't happen. It's thus possible that the choice of just one person can make the difference between there being a riot and not, as Mark Granovetter explained in his threshold model (pdf).

- Excess volatility in stock markets. Sometimes, investors herd; they buy when others buy (pdf) and sell when others sell. When this happens, we get bubbles and crashes. The shift from one to the other can be triggered by a very small cue, which stops or reverses imitative behaviour. This was the story of the 1987 crash, and it might be story of Facebook now.

What we have in these cases is the same as we have for Rutland's women - a shift in equilibrium, from peaceful behaviour to rioting, from believing an asset is cheap to thinking it's dear, and from being fat to taking exercise.

But here's the key point. Although it's possible to explain such shifts after they have happened as the result of shifts in peer effects, information cascades and social learning, they are pretty much impossible to forecast in advance.As Jon Elster wrote:

Sometimes we can explain without being able to predict, and sometimes predict without being able to explain. True, in many cases one and the same theory will enable us to do both, but I believe that in the social sciences, this is the exception rather than rule. (Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, p8)

The failure of the social sciences to make successful predictions, therefore, might reflect not a failure of science, but instead the fact that social phenomena are just so damned complex.

Sexist? I'm writing about fat women here simply because I've not noticed increased exercise among fat men.

August 17, 2012

Welfare states as investments

Tim Worstall points to the likely high earnings of successful Olympians such as Victoria Pendleton and says: "Stop subsidising the training.It’s just stealing money from the poor so that a gilded few can get ever richer." But there's a different way of looking at this.

It's that such subsidies are a form of investment in human capital. In subsidizing training, the government helps to raise athletes' earnings and it gets a return on this in the form of higher tax revenues.

Granted, the additional tax alone doesn't recoup the spending on elite sport. But it is only a fraction of the financial payback; for example, there's also lower health spending, to the extent that lardies are inspired by Olympians to get fit.

What's true for sport funding is more true for welfare spending generally; it's a form of investment which helps raise peoples' earnings and tax revenue. To this extent, the welfare state pays for itself. For example:

- Health spending patches people up and gets them back to work

- Education spending raises our earnings; if I hadn't had a state education, I'd be struggling to hold down a minimum wage job. As it is, my higher earnings have repaid the cost of my schooling many times over.

- Welfare benefits don't just keep people alive whilst they wait to get a job. They can give people time to find the right job, which raises their future earnings. And they can subsidize writers and musicians whilst they hone their craft; if it hadn't been for the dole (and an Arts Council grant), we might not have the Harry Potter books and JK Rowling's large tax payments.

You might ask why, if such spending pays for itself, the private sector does not do it, as Hopi suggests? One reason is that there are large costs of identifying the profitable investments such as those children who would benefit most from schooling. Venture capitalists find it hard enough to spot profitable companies, let alone profitable people. Another, bigger, reason is that private contracts to hand over 40%+ of one's future income are unenforceable. Only the state has the power to extract returns on investments in education and health.

So much for intuition. What of the evidence? Here are three things:

1. Between 1830 and 1870, when the UK's welfare state was minuscule, real GDP per head grew by just 1.4% a year. Between 1945 and 1985, when it grew rapidly, real GDP per head rose 1.9% per year.

2. Nordic states have for years combined large tax-funded welfare states with good economic outcomes, which suggests that big welfare states in themselves are not bad for economies.

3. Peter Lindert's research suggests that the welfare state is a free lunch. He says (pdf): "There is no clear net GDP cost of high tax-based social spending."

I say all this the welfare state is often seen as a cost. It's not. It's also an investment and perhaps a profitable one.

August 16, 2012

On retail therapy

"Retail therapy" has a bad name: we associate it with vacuous Carrie Bradshaw-types splashing out on their hundredth pair of Jimmy Choos. However, experimental evidence suggests that this image is wrong. Retail therapy actually works.

Researchers at the University of Michigan got female students to watch a film clip intended to make them sad or angry. They then gave them the option of choosing or not to buy one of six snacks. They found that women who chose to buy became less sad than those who didn't. In this sense, buying stuff cheers people up.

This could be because the act of buying simply distracts people from what makes them miserable. Two things, however, suggest this is not the case. First, women who became angry at seeing the flimp clip stayed angry whether they bought a snack or not.This is not what you'd expect if the act of buying distracted people. Second, another experiment found that people who spent time just browsing did not experience any decline in sadness.

Nor is it the case that sadness declined because people anticipated a consumer surplus from eating the snack. If this were the case, you'd expect happy people to become happier after buying. But this is not so.

Instead, something else is happening. This is that sadness is associated with feelings that one is not in control of one's. Shopping helps to restore a sense of personal control, say the authors, and so relieves depression.

This raises a question. Is retail therapy really therapy, or is it instead more like a drug which offers short-term relief without solving the underlying problem? If spending leads to higher levels of personal debt - and thus perhaps (pdf) to greater feeling that one is not in control of one's life - it's the latter.

And this in turn raises other questions. Are there not better ways in which people might regain a feeling of control than by shopping? If so, why aren't they used? And if not, why not? Those people who perceive a link between capitalism and poor mental health will, of course, have answers to these.

August 15, 2012

Success & ability

What's the link between intelligence and success? This is the question posed by Luis in a comment on yesterday's my post. He says that whilst success is no proof of ability, it could be evidence of it: "it might be reasonable to observe success and think the person is probably smart."

Luckily, we've got some nice evidence here from Mark Grinblatt and colleagues in the form of a study of the link between IQ and stock market performance for investors in Finland.

They found that the one-ninth of investors with the highest IQ made average annualized returns of between 2.2 and 4.9 percentage points more than the four-ninths of investors with the lowest IQs. All this difference came from better buys rather than better sells, and the superior performance of those buys was dissipated within a month.

For me, this suggests that the returns to intelligence are not high in the stock market; the gap between the highest one-ninth and lowest four-ninths is quite large but 2-5 percentage points of annualized returns are modest.

One reason why IQ offers such paltry returns is that intelligence (and ability generally) can lead to over-confidence, which is fatal for investors; there's evidence that this is true for intelligent investors' choices of mutual funds. Also, if a task is impossible, no amount of ability will help us do it. Just as human intelligence has not (yet?) given us cold fusion, so it cannot give us insight into the future, because knowledge of the future is (mostly and for now?) impossible to obtain. If markets are wholly efficient, IQ is wholly useless.

Of course, IQ and ability are different things.But it's not at all obvious that using a wider measure of ability would greatly strengthen the link between stock market success and ability. Although there's evidence that extraversion and femininity can make better investors, the links between these and returns are also modest.

My point here is not one about the stock market. It's about the link between ability and success generally. If this is so hard to pin down in a competitive market such as equity investing, might it also be weak in other areas of economic life? I suspect the tendency to infer ability from success owes more to the outcome bias and post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy than it does to hard evidence. If so, the tendency of the media and politicians to defer to the wealthy is mistaken.

August 14, 2012

Survival of the stupidest

In attacking Paul Ryan's "melodramatic (and incorrect) predictions about 'currency debasement'" Matthew O'Brien cites his buying of TIPS and commodity funds in 2009 as evidence that Ryan is a "true believer" who "really does think the inflation monster is about to jump out from under the bed."

Let's leave aside the fact that Ryan's buying seems to have been part of a well- (over-?) diversified portfolio. This raises an issue which has little to do with the trivia of US party politics.

The thing is, TIPS and commodities have done well since 2009. Wrongly expecting inflation to rise, therefore, has not caused investors who bought inflation protection to lose money. Quite the opposite.The Randian fanatic who piled into gold - to a greater extent than Ryan - in the wrong (and, many would add, irrational) fear of hyper-inflation did better than the more sensible investor with a more diversified portfolio.

This shows that markets do not always select against the stupid money, and can even select in favour of it. A lovely paper by Bjorn-Christopher Witte shows how this can happen among fund managers. Brock Mendel and Andrei Schleifer (pdf) and Bernard Dumas and colleagues show other ways in which it can happen.

Two examples will show how it happens in the real world:

- During the "great moderation" bankers were selected to take excessive risk; those who danced to the music got big bonuses whilst those who sat it out got sacked.

- During the tech bubble money flowed to those managers who thought boo.com and Baltimire Technologies were good stocks, whilst nay-saying managers such as Tony Dye were fired.

This matters because it rejects the Friedmanite idea that markets would tend to be stable because Darwinian selection would weed out the speculators who bought at high prices and sold at low ones. Yes, Darwinian selection works. But it can sometimes select in favour of the stupid. As Mr Witte says, "survival of the fittest" is a tautology. Sometimes, the "fittest" are simply those daft enough to go with the herd of stupid money, not those who know what they are doing*.

And this in turn has a wider implication. It means that success even in competitive markets is no proof of ability, wisdom or intellect. Sometimes, the opposite. And this might be true outside of financial markets as well as inside.

* You might object that it's rational in bubbles to go with the herd. Maybe. My point is that selection sometimes favours those who buy high, whether they do so rationally or not.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers