Chris Dillow's Blog, page 173

July 24, 2012

The state & growth

Edward Skidelsky, perhaps inadvertently, draws our attention to the difference between the social democratic and Marxian views of the state. He says:

The state...should drop the mask of neutrality and come out in favour of the good life...An economic system geared to the production of baubles and gadgets leads us away from the good life, not towards it.

This is the social democratic conception of the state - that it should help promote individuals' flourishing. To which the Marxist replies: It ain't gonna happen, chummy.

This is because, to Marxists, the principal function of the state is not to promote human thriving, except as a by-product. Instead, as James O'Connor wrote in The Fiscal Crisis of the State (which hasn't aged badly in the last 40 years):

The capitalistic state must try to fulfill two basic and often mutually contradictory function - accumulation and legitimation.

Both these functions point to the state acting against Skidelsky's conception of the good life.

In order to support capitalist accumulation and profits, the state must ensure that there's a ready supply of labour: one aim of the Beveridge report was to "make and keep men fit for service." This keeps welfare benefits sufficiently low to stop people dropping out or downsizing as Skidelsky would like, and compels them to enter the labour market.

Secondly, as part of its legitimation function, the state must supply social services such as health or education. As MacIntyre said, the state is "a bureaucratic supplier of goods and services, which is always about to, but never actually does, give its clients value for money." But thanks to the Baumol effect, the relative cost of many of these services tends to rise over time. This requires tax revenues to rise, and the least painful way of ensuring this is to pursue economic growth.

The endorsement of economic growth, then, is not a mere intellectual error of the state to be deplored by high-minded people such as Skidelsky. It is instead, a fundamental feature of it.

Now, one criticism of the Marxist view is that it is not falsifiable. If the state pursues growth-friendly policies, we say it is pursuing its accumulation function, and if it does other things we say it's pursuing the legitimation function. We win each way.

In this context, though, this criticism is wrong. If the state were to introduce a citizens' basic income - sufficiently high and unconditional to permit more people to downsize to what Skidelsky calls "simpler, less acquisitive modes of living" - then the Marxist view of the state would be falsified.

My suspicion is that this won't happen because Marxists are right.

July 23, 2012

Fiscal policy: the cognitive biases

The fact that government borrowing has risen so far this year reminds us of a key truth about the public finances - that they are less amenable to government control than generally thought. This is because government borrowing is the counterpart of private sector lending. Borrowing will fall when and only when private sector investment rises and savings fall. And this is not happening yet.

This poses a question. Given this, Why do so many people pretend that governments can easily control borrowing? I suspect it is because of a number of cognitive biases:

1.The fundamental attribution error. We tend to attribute outcomes to agency more than to situational factors. This causes us to over-estimate the extent to which the Chancellor determines borrowing and to under-estimate the extent to which that borrowing depends upon millions of private decisions to save or invest.

2. The representative heuristic. We tend to think that outcomes must somehow resemble causes, so we think that government spending and tax decisions must determine borrowing when in fact they (largely) determine the level of GDP instead. This heuristic leads us to underplay the extent to which policies other fiscal policy affect borrowing. A solution to the euro crisis, and/or effective policies to get banks lending again, would be more effective deficit reduction policies than fiscal restraint.

3. The illusion of control.People over-estimate the extent to which they are in charge of events. This might be even more true of politicians than other people because of...

4. The optimism bias. People tend to enter politics if they think they "can make a difference". This means politicians are selected for the optimism bias, the belief that they can affect events for the better.And this predisposes them to believe they can control government borrowing.

We shouldn't just blame politicians, though. These biases exist in the media as well. The Chancellor who told the truth - that he can't easily control public borrowing because private sector net lending depends upon things out if his control such as the euro crisis, banking system and dearth of investment opportunities - would be committing career suicide.

There's more. It's hard to fight against these biases in part because of the social proof effect; when so many people seem to believe something, it is tempting to go along with them.

And even if you conquer the social proof effect, there's another problem - the Overton window. When the dominant discourse is that governments control borrowing, the person who denies this becomes a crank, an extremist, and is ignored, at least by non-economists. Those who understand the public finances thus make excessive compromises to mainstream opinion, for example, by telling stories in which fiscal policy does affect government borrowing by affecting the private sector's financial balance.

Such stories will often be true - though they don't seem to have been so in the last 12 months. But they don't change the fact that the government's financial balance is merely the counterpart of the private sector's.

It was Bismarck who said that politics is the art of the possible. He should have said that it is the art of the application of cognitive biases.

July 22, 2012

The cost of law

Reading how Peter Williams was harrassed to death and Matthew Parris's account in the Times of his dealings with Leveson, the question arose: is the legal mindset a positive menace?

By this I don't mean that our laws are arbitrary and repressive, or that some lawyers are venal or incompetent. Instead, what I mean is the (over-)emphasis upon the idea that correct procedures, rules, must be followed - that what matters is due process or following codes of conduct.

This is costly. Not least is that due legal process is slow and expensive and thus imposes large costs even upon the just and innocent. Simon Singh might have won his case against the BCA eventually, but he suffered months of stress, expense and distraction. The fear of such costs leads people to avoid even the small risk of litigation, with the result that journalists are cowed by the mere threat of libel actions, missing children are not found, school trips cease, volunteering is discouraged and companies are paralysed by a fear of litigation.

It's not sufficient to point out that such fears are often based upon misunderstanding; it's entirely reasonable for people to want to avoid a small risk of the high cost of finding out.

Yet another cost is that, just as financial rewards can crowd out other motives, so law can crowd out ethical behaviour. Philippe Aghion and colleagues have shown how regulations can breed distrust, as companies behave to the letter of regulations rather than spirit.

Just as due legal process doesn't prevent guilty people being acquitted or innocent ones convicted, so regulations and codes of conduct don't necessarily guarantee that business will behave well. The highly regulated pensions industry, for example, continues to rip off savers, and journalists might be right to fear that a post-Leveson code of conduct will do little to promote good journalism.

Rules do not guarantee virtue or wisdom. The coalition's fiscal policy, for example, is lawful - but it is uninformed by evidence or rationality.

In light of all this, it shouldn't be surprising that there's some evidence that large numbers of lawyers can be bad for long-term growth (pdf).

What I'm saying here is that lawyers are not necessarily objective arbiters of trust or efficiency. They have their ideologies and blindspots just as any professionals do - a stress upon rules rather than virtues, and on processes rather than outcomes.

In saying all this I am not denying that there's a place for a legal mindset. There certainly is. But this mindset must not dominate society, any more than should the mindset of engineers, doctors and - yes - economists. To believe otherwise is to commit the fallacy of deformation professionelle. My concern is that the pomposity of the legal system - "the majesty of the law" - and politician's fetish for judicial inquiries prevents people seeing this.

July 20, 2012

Coops, trust & growth

Here's some important new research:

Cooperative enterprises can create social trust among workers, unlike any other type of enterprise...

The development of cooperative enterprises – and, more generally, of less hierarchical models of governance and of not purely profit maximizing forms of enterprises – may play a crucial role in the diffusion of trust and in the accumulation of social capital.

This matters not merely because trust and social capital are intrinsicially good, but also because trust helps raise long-term economic growth.

Three quick observations:

1. This highlights a fact sometimes forgotten by today's managerialist politicians but understood by classical thinkers such as Tocqueville - that institutions shape culture. And culture, in turn, affects economic growth.

2. Insofar as coops promote trust, they contain a positive externality - because the benefits of trust accrue to everyone and not just coop members. This suggests that relying merely upon private incentives to create coops could result in a suboptimally low supply of them.

3. The "coops create trust which promotes growth" view challenges a conventional approach to growth expressed today by Sam Brittan:

Let governmental authorities concentrate on securing conditions for as near as practicable full employment without inflation and removing distortions at the micro level. Then let the growth rate emerge as a byproduct of the activities of individual citizens.

This overlooks the possibility that hierarchical capitalism itself might be a barrier to growth.

July 19, 2012

Luck, & helpful illusions

Here are four pieces of recent research:

- children whose fathers lost their jobs in the 1980s recession did worse (pdf) in school and went on to earn less than otherwise similar children whose fathers kept their jobs.

- good-looking men earn more than ugly ones at any level of earnings.

- children who are bullied at school before the age of 12 go on to get worse grades and are more likely to take drugs or get pregnant in their teens.

- children who are taught in small classes between ages 10 and 13 go on to earn more in middle age than those taught in larger classes.

These apparently different findings have one thing in common. They all show that our fate in life depends upon luck. It's a matter of luck whether your dad kept his job or not; whether you are ugly or not (make-up doesn't get you far (pdf)); whether you're bullied or not; and how big your school classes were.

Granted, the average effects in these papers are smallish. But they are only a tiny subset of the ways in which luck affects us. Whether we get teacher and mentors who inspire us or not, whether we enter (pdf) the labour market in a recession or boom, whether we're members of the lucky sperm club or not and - most importantly - whether we are born in England or Ethiopia are all matters of dumb luck.

Ed Smith is surely right. Our success, or not, in life is surely a matter largely of luck. I can easily imagine that slight tweaks in my fortunes would have made me either a multi-millionaire or a convict - and I suspect the same is true for most folk.

In saying this, I am not taking a purely leftist position. In Law, Legislation and Liberty (ch 8), Hayek said that income inequalities between people "will often have no relations to their individual merits"and decried it as a "misfortune" that people defended free market on the erroneous grounds that they rewarded the deserving.

I fear, though, that mine, Smith's and Hayek's position is a minority one.Far more common is the belief that the successful have earned their rewards whilst the poor should work harder. Why do people belief such nonsense?

The obvious answers lie in cognitive biases. The just world fallacy causes us to find justifications, even spurious ones, for injustice. And self-serving biases cause the successful to believe that success and failure are due to individual effort - and, of course, the opinions of the rich carry far more weight in politics than those of the poor.

But how costly are these illusions? Hayek pointed out that they can have big benefits. The belief that our well-being depends upon our own efforts will spur us to study and work harder than we would if we thought our well-being merely a matter of fate. And this greater effort can make us all in aggregate better off.

There is, then, a trade-off between truth and utility.

July 18, 2012

Unemployment: a brief history

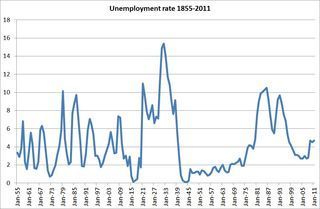

My chart below puts today's unemployment data into long-term historical perspective. Using Bank of England data, it shows the unemployment rate since 1855.

What stands out here is that a highish rate of joblessness is quite normal. It is the 1945-73 period of full employment (for men!) that is historically odd, not today's joblessness. In fact, between 1855 and 1939 the unemployment rate averaged 5.1% - higher than the claimant count rate is now.

I reckon there are several important messages here:

1. Marxists are right. From the point of view of workers, capitalism tends to stagnation, in the sense of being unable to provide work for all. Michal Kalecki was spot on: "unemployment is an integral part of the 'normal' capitalist system."

2. The idea that free market policies can generate sustained full employment lacks any historical foundation, unless you want to argue that there were severe labour market regulations that caused mass unemployment in the 19th century; "Damn those Factory Acts!"

3.Claims that the welfare state has created a culture of dependency in which folk don't want to work look silly. High unemployment was the norm in the pre-welfare state era.

4. Unemployment is not merely a cyclical problem remediable merely by counter-cyclical macroeconomic policies. It is more permanent than that.

5. If we want full employment - and we should - we need something like the post-war settlement. Which poses the question of whether this is feasible. Personally, I fear it's not; the post-war reconstruction and Fordist manufacturing which created ample jobs for the unskilled are gone for good.

6. If full employment is impossible under capitalism, the question arises: how can we mitigate the misery it causes? I'd suggest active labour market policies that do not stigmatize job-seekers, and a more generous welfare system (clue - basic income.) But I don't expect such suggestions to be heeded.

Help for right-wingers: the data are consistent with the idea that there are lots of people who are unemployable, but that this has always been so, except when demand for the unskilled was very high in the post-war era.

July 17, 2012

When organizations fail

The G4S fiasco has led some to question - not necessarily consistently - whether the private sector is any more efficient than the public.

For me, the question makes little sense as an ideological one. Hierarchical organizations are prone to failures arising from adverse incentives, limited knowledge and bounded rationality (planning fallacy, anyone?).What matters is how organizations mitigate these dangers; whether they are in the public or private sector is not often the issue.

There is, however, a common claim - one I think I've made myself - I want to challenge. It's the idea that market forces mean that the failure of private sector organizations is less catastrophic than public sector ones.

Now, in many cases, this is true. When Woolworths collapsed, there was no generalized crisis; people simply bought their pic 'n' mix elsewhere. By contrast, when the "Border Force" screws up, people cannot use other means to get through immigration checks quickly.

What interests me, though, is that there are cases where private sector failure does have costs - and I don't just mean the fleeting political embarrassment that arises from G4S's failure.

The biggest and most obvious example of this was, of course, the banking crisis. It showed us that the collapse of a handful of organizations can have colossal macroeconomic effects.

I'd suggest three general ways in which private sector failures can have macroeconomic effects:

1, Common failures. If every organization is pursuing the same strategy, then any change which causes the strategy to lose money might kill off all organizations in an industry. Markets are like ecosystems (pdf).If there's insufficient biodiversity, environmental change will wipe out entire ecosystems.This is the story of banks.

2. Market blockages.Ashwin says: "When the incumbent fails, there must be a sufficient diversity of small and new entrants who are in a position to take advantage." But this is not assured.For it to be true we need (among other things) an entrepreneurial culture, a lack of barriers to entry and expansion and finance for entry and expansion. None of these are assured.

3. Being big enough to matter.As Xavier Gabaix has pointed out, some firms are sufficiently large that they matter for aggregate growth. The failure of one or two mega firms might then generate the sort of adverse productivity shock that RBC theorists fret about.

I reckon there are (at least) two implications here.

First, the standard macro-micro division of labour in economics can be dangerous, as it can blind us to the fact that micro failures can have macro effects.

Secondly, the question of whether private sector firms are well or badly managed cannot be left to the market, and nor can they be rectified by macroeconomic policies. The question of how private sector firms are managed is a legitimate political one. And this raises issues which the non-Marxist left has tended to ignore for too long.

July 16, 2012

When were we Keynesian?

The government has announced a big investment in infrastructure - to start in 2014. If you believe the OBR's forecast for economic recovery, this means the investment will come just after the economy most needs a boost.So much for Keynesianism.

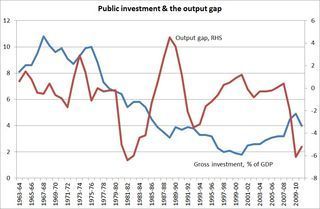

This set me pondering. Just how counter-cyclical has public investment in infrastructure been in the past?

My chart suggests: not much. If spending were counter-cyclical, you'd expect to see a negative correlation between gross public investment as a share of GDP and the output gap, with recessions causing high spending and booms lower spending. But in fact, there's no such relationship. According to Treasury/OBR data, the correlation was zero between 1963 and 2010*.

You might find this surprising, because you don't need to be a Keynesian to believe that infrastructure spending should be countercyclical. If real interest rates fall in recessions, you only have to think it's a good idea to borrow more when interest rates are low to want a negative correlation between the output gap and infrastructure spending.

So, why haven't we had one? Anti-Keynesians could argue that it's just impossible for governments to behave in a Keynesian way.The time lags involved in finding and planning big investments mean they cannot be started when the economy is weak. Alternatively, perhaps investment decision have been driven more by politicians'vanity - a desire for grand projects such as Concorde - than by economic logic.

Good points. But they run into a problem. If we split our data sample into three periods, we find different, and negative, correlations: -0.1 for 1963-79;-0.56 1979-97;and -0.85 for 1997-2010.

What we have here is an example of Simpson's paradox.

In other words, both the Thatcher/Major governments and New Labour behaved Keynesianly, having higher investment in booms and slumps. For example, Thatcher cut infrastructure spending as the economy moved from recession in 1981-82 to boom in 1988-89.

If anything, it was the pre-1979 governments that were not so Keynesian, having only a weak correlation between the output gap and investment. The golden age of Keynesianism was no such thing.

In this sense, Cameron's announcement of rail investment represents a return to pre-Thatcherism.

* In theory, this could be because governments have seen recessions coming and increased investment in anticipation of them with the result that recessions haven't materialized, and so there's been no correlation between spending and the output gap. But I don't think anyone thinks this has been the case in practice.

July 13, 2012

Trust cycles

I've suggested that potentially the biggest cost of the Libor fiddle is that it might depress trust in the economy and hence long-run economic activity. Coincidentally, a new paper half-corroborates my fear. It says we can be "locked into cycles in which trust and trustworthiness emerge and collapse again and again."

Think of a trust game. In this, one person - the investor - decides whether to give money to another, the trustee. If he does give money, the experimenter triples the sum. The trustee then chooses whether to give any money back.

Experiments show that investors often do hand money over, and trustees hand some back. This contradicts the ideas that people are rational selfish maximizers, as this predicts that the trustee will keep all the money for himself.

But what if the game is repeated, with investors choosing trustees?

Imagine that some trustees then behave badly and don't return money. Investors who trust will then lose money. In evolutionary terms, they'll be selected against and will die out. Trust will then decline. And it might not be rebuilt merely by state regulation (pdf) of trustees. If it declines to zero, no investor will hand anything over to trustees, so trustees will end up with zero return as well.

But when trust is low, the trustee who can somehow signal his trustworthiness will attract more investors than his untrustworthy competitors. As an example, think of those 19th century food manufacturers such as Bird's, Colman's or Cadbury's who invested in brand reputation to signal that their products were less adulterated than their rivals'.

Trustworthiness will then be selected for, and so will spread. And as this happens, investors who trust will earn bigger returns, and so selection instead of favouring the untrusting will now favour the trusting. Both trust and trustworthiness will then rise. But when trust is very high and investors are handing over big money, trustees will have stronger incentives to run off with the money.

So, we get cycles of rising and falling trust and trustworthiness.

There are several implications here:

1. Homo economicus - the selfish rational maximizer - does not necessarily create a prosperous society. This is because homo economicus might have an incentive to run off with the money. A society of such people might therefore be a low trust one - and therefore poor.

2. Both trust and trustworthiness have positive externalities; they benefit others, not merely ourselves. This suggests they might be under-supplied by homo economicus.

3. There need not be stable equilibria of high or low trust. When trust is low, trustees have an incentive to be trustworthy. And when it is high, they have an incentive to defect. This gives us cycles.

4. Matthew's contention that "everything is leveraged" - small changes can have big and longlasting effects - is valid. A smallish loss of trustworthiness or trust can set us on the downward leg of a cycle. Which is why banks' misbehaviour is worrying.

July 12, 2012

Crony capitalism - the only capitalism

Supporters of free markets seem to be increasingly vocal in their opposition to corporatism or crony capitalism. Whilst I wholly welcome this, I fear that the demand for a proper free market economy without cronyism or special favours is as unachievably utopian as the wildest leftist fantasy.

I say this because of the first premise of free market economics - that incentives matter. Politicians want money, business wants influence and favours. Both sides therefore have powerful incentives to trade - to give us cronyism.

Of course, this wouldn't be a problem if there were, as Sandel and Walzer have argued, moral limits upon markets - an agreement that there should be some things, such as political power, that money shouldn't buy.But this ethical demand runs into the fact pointed out by Marx - that the logic of capitalism is commodification, the extension of the cash nexus:

The bourgeoisie...has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”...It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade.

There's another reason why crony capitalism will always exist. As Arnold Kling says, there will always seem to be a good argument for regulation. And thanks to regulatory capture, an inevitable by-product of this will be that regulation will favour big business; this fact is now so obvious that it even Liberal Conspiracy and a Very British Dude agree upon it. The only way to avoid cronyism is to avoid regulation - and nobody wants this.

There's a third point, which I think is under-appreciated. To survive - let alone thrive - in a proper market economy requires great entrepreneurial skill, to be flexible, efficient and genuinely "customer-focused". But these skills are very scarce. In a true market economy, therefore, not only would entire industries such as banks and arms companies not exist in their current forms, but nor would many firms, such as G4S, A4E or Atos. State support for business is necessary to sustain demand for the vast supply of incompetents and fraudsters.A free market economy would be one in which many people are unemployable.

Crony capitalism, then, is the only feasible form of capitalism.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers