Chris Dillow's Blog, page 168

October 1, 2012

Framing worker democracy

Nicola Smith says that predistributionist policies should include greater workplace democracy. I agree. What worries me though is the framing of this issue. I fear there's a danger that the call for workplace democracy will be seen as a demand made by a sectional interest. It shouldn't be.

Instead, it should be a response to the fact that capitalist control of firms has failed. I mean this in three senses:

- The collapse of banks shows that shareholders do not monitor managers well. They lack the incentive to do so, because their share ownership of any firm is typically only a small fraction of their wealth. And they lack the knowledge to do so too, because outsiders normally know less about what's happening in a firm than do insiders such as key workers.

- Capitalists have largely ceased to be providers of capital.For most of the last ten years, non-financial firms, in aggregate, have retained more in profits than they have spent on capital equipment. And except for the recapitalization of banks, net share issuance has been small or negative in recent years.

- Capitalist control of firms might not have solved a problem thought to bedevil coops, that workers have short-term time horizons. Capital can be as short-termist (pdf) as labour - or maybe more so (pdf).

These failings suggest that the case for greater worker control should be framed not as a sectional demand, nor as a case for greater equality, but as one of efficiency. Quite simply capitalist ownership of firms is (often? sometimes?) inefficient; I hesitate to call it capitalist control, because firms' nominal owners exercise pitifully little control.

The case for worker ownership and control is a Blairite one: what matters is what works, and worker democracy works.

I suspect the persistence of capitalist firms is in some cases an example of path dependence. It exists now largely because it existed in the past. Granted, there was a time when capitalist ownership and control made sense: when they did provide capital; when workers were easily monitored; and when capital-owners knew more about the business than workers. But the days of 19th century mill-owners are gone. So why should the ownership structure that made sense then persist?

To put this another way, if we had worker control and ownership today, under what circumstances would the demand for a shift to capitalist control and ownership make sense?

I stress here that I'm not arguing for the overthrow of capitalism; the question of the merits of worker vs capitalist control will vary from place to place, as this long pdf describes. All I'm saying is that the call for worker democracy should be framed within a context of a widespread failure of capitalism.

September 28, 2012

Getting high on your supply

One of the first rules of drug dealing is, as Elvira Hancock said, "don't get high on your own supply." Two things I've seen today suggest that journalists should aspire to the higher standards of drug-dealers.

First, Allister Heath says it is "no longer tolerable" that the ONS revises its initial estimates of GDP so much. He says of the first estimate that GDP fell 0.7% - since revised to 0.4% - in Q2:

The impact on politicians, economists and corporate executives who obsess about the minutiae of these figures will have been significant. CEOs may have delayed investment plans on the basis of flawed figures.

This is tosh. The reaction of many economists to that first estimate was simply not to believe it. And whilst I have a lower opinion of CEOs than most, even I don't think they are so imbecilic as to base investment plans on GDP numbers (clue - time moves forwards, not back).

In fact, the ONS told us not to believe it.It accompanied the number with a table showing that the first estimate of quarterly GDP growth is revised by an average of 0.3 percentage points. And it said its Q2 estimate "may be subject to greater uncertainty than usual."

Such revisions are, in truth, inevitable. A £1.5 trillion economy cannot be measured quickly and accurately.

The only people who can possibly be remotely upset by the ONS's revision are those journalists who got high on their supply - who were daft enough to believe their information suppliers.

Which brings me to my second example - Kelvin Mackenzie's account (£) of his part in the Hillsborough libels. He asks: "Why shouldn't I believe what four senior officers had told the partners of a local news agency?"

Simple. Whilst the police have little incentive to lie in the normal course of duty - when they are telling journalists about crimes by other people - they have every incentive to lie when trying to distract attention from their own murderous incompetence. Econ 101 should have told Mackenzie to be sceptical.

But he wasn't. If we are to believe him (and I'm not sure we should, but let that pass) he got high on his supply.

Of course, it's entirely reasonable - correct even - for journalists to report economic statistics and the words of policemen. It is, however, another thing entirely to believe them.

My point here is not merely about Mackenzie and Heath. It's about journalism generally. I suspect that, quite often, the reporting of the words of "senior" people - not just policemen but also politicians and businessmen - becomes the believing of those words, or at least the insufficient scrutiny of them. And this helps to support those in power, even if they are downright dishonest.

September 27, 2012

Reactionary postmodernism

There's one thing not happening today which should be. People are not ridiculing Nick Clegg, at least no more so than usual. But they should be, because one part at least of his speech yesterday was downright stupid:

Who suffers most when governments go bust? When they can no longer pay salaries, benefits and pensions? Not the bankers and the hedge fund managers, that’s for sure. No, it would be the poor...

Of course, this is plain wrong. In countries with their own central banks, governments cannot go bust because the central bank can simply print money to buy government debt: this is what QE is. Of course, this might or might not be a bad idea. But Clegg didn't argue this. He just made a prat of himself.

However, my point is not to condemn Clegg; I'll not flog that dead horse. Instead, it's to note that the MSM seem to have ignored this. His speech was reported with the usual post-conference bromides rather than along the lines of "Deputy Prime Minister shows himself to be crass idiot."

There are two things going on here.

First, the Overton window has shifted so far away from rational policy discussion that blatant falsehoods not only do not provoke the derision they deserve, but actually go unchallenged.

Secondly, this is another example of fact-free politics. Despite Edward Docx's obituary last year, postmodernism is alive and well.

Which brings me to what's really troubling about Clegg's remark.Docx claims that postmodernism was a good thing because:

Once you are in the business of challenging the dominant discourse, you are also in the business of giving hitherto marginalised and subordinate groups their voice.

The fact that Clegg can get away with errant nonsense challenges this optimism. In a postmodern world in which all all discourses are equally valid regardless of their truth-value, the claims of the ruling class are not exposed for the lies and imbecilities they are. Postmodernism as it actually exists - that is, with a supine media - thus helps to serve a reactionary function.

September 26, 2012

The impossibility of meritocracy

Should you hire the best-qualified candidate for a job? The answer is: not necessarily, as a new paper points out.

The reason for this is simple.It's to do with induced reciprocity.If you hire a duffer, he'll feel grateful to you and will exert more effort or honesty. The best-qualified candidate, by contrast, will feel entitled to the job and so might not try so hard.And it's possible that what you gain from his greater ability you lose from his lesser diligence. The authors show that, under experimental conditions, a big minority (30%) of principals choose a mediocre agent for just this reason.

I suspect this is a classic case of economists seeing something in practice and wondering how it can happen in theory. We've all seen second-rate people get jobs because the boss trusts them; we might even have been that second-rater ourselves.

This is not the only reason why rational bosses might hire lacklustre people. Marko Tervio has shown that, when talent can only be revealed by working with expensive assets, bosses will prefer a known mediocrity to potentially better but unknown workers.And Dan Bernhardt, Edward Kutsoati and Eric Hughson have shown how managers prefer to hire people like themselves whose skills they can more easily evaluate.

And this is not to mention plain nepotism, Adler superstars, the demand for quacks or survival of the stupidest effects.

Hayek, then, was correct when he said that "the return to people’s efforts do not correspond to recognizable merit."

The point here is related to one Will makes. Meritocracy, at least as normally understood, does not exist and probably cannot exist in a free market with rational people.You cannot therefore justify inequalities by claiming that they reflect differences in ability - though there are, of course, less bad justifications.

The claim that successful people often lack talent is not just envy-tinted casual empiricism. It is entirely consistent with economic theory.

September 25, 2012

Subsidizing newspapers

Do newspapers provide a public good that wouldn't exist in their absence? It's that question that should determine our reaction to David Leigh's proposal for a £2 per month levy on broadband to subsidize newspapers.

There is some evidence to support him. When the Cincinnati Post closed in 2007, voter turnout fell and incumbent councillors were more likely to be re-elected, suggesting that the decline of even small newspapers worsens democracy.

However, I'm not sure this is a clinching argument, for four reasons:

1. The MSM isn't just a public good, but a public bad. The likes of Richard Littlejohn, Rod Liddle and some parts of Comment is Free help to coarsen and devalue political discourse. So too do journalists' sloppy (pdf) thinking and lazy churnalism. It's not obvious why low-paid workers and highly-indebted graduates should be forced to pay more so they can top up Paul Dacre's £1.7m salary. Granted, local newspapers are more of a public good - but Leigh's proposal won't much help these.

2. Leigh's proposal to subsidize papers "in proportion to their UK online readership" provides an adverse incentive. It would further incentivize cheap linkbaiting rather than expensive investigative journalism.

3. It's not clear that newspapers provide much news or analysis that isn't available elsewhere, most notably on the BBC. In today's Times - to take the example nearest to hand - there seems to be only one exclusive UK story of public concern. In economics, do newspapers really tell you much that you couldn't get from the BBC, the ONS or our better econobloggers?

4.It's possible that if newspapers were to disappear, other forms of journalism - some unforeseeable - would expand to fill the gap. Subsidizing newspapers thus helps keep dinosaurs alive and retards the creative destruction that might give us a healthier journalism.

On balance, then, I don't see much merit in Leigh's idea. The case for subsidizing newspapers is about as strong - and arises from the same motive - as my belief that the government should subsidize left-handed cat-loving guitar-playing economists.

September 24, 2012

Markets vs morals

Do markets inherently create bad incentives? Two recent experiments by Michele Belot and colleagues suggest so.

First, she got people to spend ten minutes identifying the country of origin of euro coins, with payment either as a fixed wage, piece-rate or as a competition with a prize for the winner. She found that productivity was 15% higher with piece-rates than a fixed wage, and 13% higher still with a pure competition. Competition, it seems, raises productivity. But it also increases cheating; subjects in ther competition over-reported the number of coins they identified much more than subjects in the other payment methods.

In a second experiment, she got subjects to make choices that affected others' payoffs. She found that in small groups where the effect of the choice on others was clear, people were more likely to behave altruistically than they were in larger groups where the harm to others - though just as large - was less salient.

All this suggests that whilst market forces have an upside - increased productivity - they also have a downside. They can encourage cheating and - insofar as market relations can be anonymous - they can crowd out altruism.

Although some people think that laboratory experiments in economics might not be always applicable to "real life", these findings chime in with real world experience. Strong competition between newspapers led to the phone-hacking scandal, whilst competition in banking has led to various episodes of mis-selling.

There is, though, a complication here. In that coin-identifying experiment, Ms Belot found that 94% of the cheating was done by just 19% of participants. This suggests that it is not the case that competition encourages everyone to cheat. For most people, social norms (or conscience) keep them honest. Instead, competitive incentives encourage misbehaviour by a minority.

The point here is not a simple one about markets and competition being good or bad. Instead, it's that they have ambiguous effects, and their desireability or not might be very sensitive to contexts, pay-offs and pre-existing social norms.

September 22, 2012

Fact-free politics

Chris Skidmore, one of the authors of Britannia Unchained, says:

People aren’t interested in looking at medians and graphs. We have a duty to try and broaden that message outside of the think tank zone.

I don't know what to make of this. It could be that Skidmore is recommending that politicians use social science in the way Paul Krugman urges economists to use maths - you base your policy upon it, but then find a way of advocating the policy in more populist language.

Sadly, though, it is not at all obvious that Britannia Unchained's authors are using this resonable approach. They seem instead to have skipped the science and evidence and gone straight to the populism.

This suggests an unkinder interpretation - that Skidmore thinks formal science has no place in politics. What matters is what sells, not what's right.

The problem here is that there is no strong obstacle to this descent into post-modern politics. The anti-scientific culture of our mainstream media means they will not call politicians out on their abuse of facts, unless the abuser is not in their tribe - as Jonathan complained in noting the press's reaction to Britannia Unchained.

But does this matter? In one sense, maybe not. Expert support and empirical evidence does not guarantee that a policy will be a success - though I suspect it improves the odds.

Instead, what worries me is that this threatens to further corrode the standard of political discourse.Fact-free politics need not be the sole preserve of the right; some of my readers will have the name of Richard Murphy in their minds. And if we go down this road, we'll end up with one tribe thinking the poor are all scroungers and the other thinking our economic problem can be solved by a crackdown on tax dodging. And the two tribes will just be throwing insults at each other. And there's a few of us who think this would be dull.

September 20, 2012

Distrusting distrust

It's long been a commonplace that people don't trust politicians - even less than they claim to trust bankers. Looking at the reaction to Clegg's apology, though, I wonder if this is really the case.

What I mean is that, if we didn't trust politicians, our reaction would be: "That's all right, mate. I never believed you anyway." But this reaction - which was mine - doesn't seem to be the majority one. Some people seem to have voted Lib Dem on the strength of their tuition fees pledge, and Clegg's apology has revived their outrage. Insofar as such hostility is genuine, rather than the manufactured offence of our emotionally incontinent age, it is a symptom of people who trusted politicians and feel betrayed, not of those who distrusted them.

This is not the only - or even the main - reason to doubt that politicians are distrusted. At least three things you'd expect to see in a nation of low political trust are weak:

- Falling voter turnout. Yes, turnout is lower than it was in the 60s and 70s. But there are other possible reasons for that than distrust. And turnout has actually risen in the last two elections.

- A big black economy: if you don't trust politicians, you'll be loath to pay tax. But the UK's black economy isn't unusually large by international standards.

- A strong demand for limited government.If you distrust politicians, you'll want them to do as little as possible. But, like it or not, libertarianism is a nugatory political force. More people say they want higher spending and taxes than lower (though I'm not sure we should believe them on this either).

This poses the question. Could it be that people's claim to distrust politicians is, to some extent, mere cheap talk? People say what they are expected to say. They want to conform to the bar-room cliches that politicians are all in it for themselves and that they are canny enough to see through their lies. But in fact, this is just talk, and more people behave as if they trust politicians than actually say they do.

All I'm saying is that it's not just politicians I distrust. It's the voters as well.

September 19, 2012

A Tory case for delaying cuts

In the Times, Danny Finkelstein argues against a temporary fiscal loosening:

Summoning up the will and retaining the minimum of political support is incredibly difficult. And fragile...Once we return to a policy of borrow and spend, how will we ever summon up the will to stop again?

I'm not sure about this. If I were a Tory wanting smaller government - and this, rather than concern about the national debt, is the reasonable argument for cutting public spending - I'd have three concerns.

1. Delaying cuts gives us the chance to make more intelligent ones. It gives us the opportunity to consult workers on where best to make efficiency savings; these are better identified from the bottom-up than from the top down. Quick cuts are bad cuts, which risks discrediting the aim of shrinking the state.

2. Cutting spending at a time when the private sector is weak isn't just a bad idea on Keynesian grounds. It's a bad idea politically. Support for cuts could be undermined by guilt by association with a weak economy.

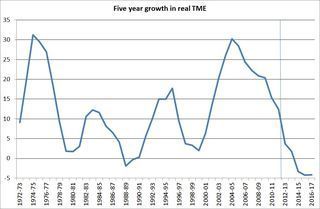

3. History suggests that cuts now are a substitute for cuts in the future. My chart shows the point. It shows five-yearly growth in real total managed expenditure. Since the 70s there have been three periods of significant restraint: the five years to 1981, the late 80s and late 90s. All three were followed by periods of high spending. "Prudence", then, has not been a habit in the past. Quite the opposite.

This poses the danger that spending cuts now will be followed by a splurge later. Not only might this be a bad idea on Keynesian grounds - the splurge might add to strong growth and be potentially inflationary - but it would also unravel any progress towards a smaller state.

What I'm suggesting here is that it's not just Keynesians who should argue for postponing restraint. There's a case for intelligent Conservatives to do so as well. But this is the opposite of what's planned; on current policy, real TME sees its biggest fall this year, and a rise in the years after.

But then, do the Tories want to cut spending out of a genuine desire to see a sustainably smaller state? Or are they instead motivated by silly fears about the national debt and by a hatred of public sector workers and benefit claimants?

September 18, 2012

Counterproductive campaigns

Does the "no more page 3" campaign have something in common with the protests against the Innocence of Muslims video?

What I mean is that both might be examples of counterproductive campaigns - political action which doesn't just fail (as most politics does) but actually backfires.

In a world where pictures of topless women are common, page 3 is an anachronism. I suspect that the Sun keeps it precisely because doing so signals the paper's rejection of "feminazi" political correctness.To this extent, page 3 persists not despite feminists' objections but because of them, and so the campaign against page 3 is actually counterproductive.

In this sense, the campaign is like those Muslim riots. In showing that (some) Muslims have the emotional maturity of a four-year-old child the protests do more to discredit Muslims (at least among those prone to the outgroup homogeneity bias) than that idiotic video did.

These are not the only examples of counterproductive politics. I suspect that people are repelled from far-left politics by its association with folk who have nothing better to do with their time than stand on street corners selling newspapers.And the concept of negative credibility - "never believe anything until it's officially denied" - tells us that some political utterances are worse than useless.

There are at least three mechanisms through which political action can be counterproductive:

1.By polarizing one's opponents. This could be what's happening with page 3. And it happens if thinking about one's opponents merely strengthens one's own hostility to them.

2. If the messenger discredits the message.This happened twice on Newsnight last night, when Toby Young tried to defend Tory policy on GSCEs and Jacob Rees-Mogg - a man who looks as if his only knowledge of the welfare system is that one of his junior footmen claims tax credits - discussed benefit reform.

3. The Streisand effect. Sometimes, a campaign can help mobilize overwhelming opposition to it.Argentina's invasion of the Falklands, for example, backfired horribly when quiet diplomacy might have had some success.

I suspect that political activists give these mechanisms insufficient thought: why else does the Tory party allow Rees-Mogg to appear in public? There might be a reason for this, beyond the fact that people don't appreciate the power of obliquity. A lot of political activity is motivated not (just) by a desire achieve a goal, but by what Robert Nozick called symbolic utility, the desire to express the type of person one is. The problem is, though, that sometimes there's a sharper trade-off between symbolic utility and instrumental rationality than generally realized.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers