Chris Dillow's Blog, page 161

December 30, 2012

The costs of hierarchy

Experimental evidence shows that hierarchical organization is more inefficient than generally realized.

Ernst Fehr and colleagues got subjects to play an authority-delegation game, in which subjects were divided into principals and agents, and then asked to work on selecting projects with varying payoffs. They made two important discoveries.

First, subordinates put in less effort than you'd expect rational income maximizers to; depending on the treatment, up to half put in no effort at all, even though this was almost never the income-maximizing option.

This corroborates Jeffrey Nielsen's claim that rank-based thinking demotivates ordinary workers - and is consistent with the BBC's Newsnight fiasco.

One reason for this, says Fehr, might lie in regret aversion. People have an aversion to being treated unfairly - which is why they reject unfair but wealth-enhancing offers in ultimatum games - and the fear of not getting a fair reward for their effort makes them loath to work.

This suggests that the trade-off between the allocation of control rights and provision on incentives is greater than conventional theory (pdf) predicts.

Secondly, Fehr and colleagues say:

We find a strong behavioral bias among principals to retain authority against their pecuniary interests and often to the disadvantage of both the principal and the agent.

Some two-fifths of principals did not delegate even when income-maximization required it. This suggests that people get a non-pecuniary buzz from being in control, and seek this benefit at the cost of economic payoffs to themselves and others. This is consistent with the findings of other experiments by Fehr and colleagues, which suggests that hierarchy facilitates exploitation rather than pure economic efficiency.

All this represents a challenge to conventional transactions costs economics, as developed by the likes of Oliver Williamson, which predicts that hierarchy is efficient (pdf) in many plausible conditions. And this poses a challenge to defenders of hierarchical capitalism: do real-world mechanisms such as competition between firms strongly select against the adverse effects of hierarchy which we see in experiments? My suspicion is: perhaps not.

December 28, 2012

Debuncification

Reading Danny Baker's autobiography over Christmas shed light on an aspect of economic history. He writes of his docker dad:

Getting things 'out of the docks' was considered a perk of the job. At one time, any working person who considered a new job would have to factor in what their bunce quotient might be. Bunce can be simple office stationery, or a good supply of cream horns if you work in a bakery. Or, as in the case of my brother's mate Billy who landed a job at the Ford plant in Dagenham, you could see everyone in south-east London all right for tyres and driver's side mats throughout the 1970s.Bunce, and the distribution thereof, lay at the very heart of the working-class community. (Going to Sea in a Sieve, p27)

This corresponds to my memory of the era; pater was a lorry driver who rarely arrived at his destination with a fuller load than he set off with. It's no accident that Fools and Horses and Steptoe and Son were hugely popular sitcoms, and that "Shoplifters of the World Unite" was an anthemic song of the 80s, because these spoke to the fact that we were all ducking and diving.

But this, I sense, is no longer so. This is not because we have been overcome by a fit of morality, but because of (among other things), technical change and more rigorous management. Containerization has frustrated dockers' and lorry-drivers' freedom to redirect goods; CCTV has made shoplifting and pilfering riskier; electronic tills have reduced shop assistants' flexibility in ringing prices; and management now take a more sceptical view of expenses claims than they did a generation ago.

I suspect, then that in important ways, the economy has debuncified since the 70s. If I'm right - and of course the data are little help - this might have several implications:

1. Some of the growth pick-up since the 1970s might have been due not to genuinely better economic performance, but to a shift from a bunce economy to a "legitimate" economy. For example, a fall in the bunce economy from 10% to 5% of GDP over a decade is sufficient to lift measured GDP growth from 2% a year to 2.5%. That's a lot. And the magnitude might be even greater in economies with bigger shadow sectors.

2. This might help explain the Easterlin paradox. If the measured economy grows because of debuncification, people won't really be better off - so (measured) GDP growth won't bring extra happiness.

3.Measures to stamp out bunce boosted profits more than wages, and so might help explain the rising profit share between the mid-70s and mid-90s.

4.Debuncification might have contributed to the low growth in (measured) wages of less skilled workers. Technical changes have allowed managers greater direct oversight of workers which in turn has reduced the need to pay them efficiency wages in order to try and keep them honest.

5.One reason why economic growth has slowed in recent years - and why the profit share stopped rising after the mid-90s - might be that technology-driven debuncification has simply run its course.

Of course, I'm not saying that debuncification is everything - merely that it might be an overlooked part of the economic history of the post-70s period; we must always ask of any piece of data such as GDP: what exactly is this measuring and what not? Nor, of course, am I saying that the theft economy has disappeared. It hasn't. It's just that, these days, it is bosses and not workers who are engaged in it.

December 20, 2012

The ownership question

Here are four issues which have something in common - something which is overlooked by much of the left:

- Can we introduce a living wage without pricing some workers out of jobs?

- Can we tax companies more heavily without them moving their profits overseas, or cutting investment or shifting the burden onto workers or customers?

- Are there some macroeconomic policies - fiscal policies, wage-led growth, NGDP targeting (pdf) or whatever - that can create near-full employment?

- Is it possible to regulate banks sufficiently to avoid another financial crisis, whilst ensuring that they lend sufficiently to productive businesses?

These look like separate issues. But in one sense they are not. They are all different facets of the same question: how far can governments influence corporate decisions when they do not have direct ownership or control?

My answer, as regular readers know, is: not far. But that's not my point today. My point is rather that the non-Marxist left doesn't ask this question, but merely begs it.

In this context, the legacy of Keynes is a malign one. Although Keynes spoke of a "comprehensive socialization of investment", he swiftly mitigated this:

It is not the ownership of the instruments of production which it is important for the State to assume. If the State is able to determine the aggregate amount of resources devoted to augmenting the instruments and the basic rate of reward to those who own them, it will have accomplished all that is necessary.

And here;'s the problem. The "if" in that second sentence is a big one. For decades, however, the social democratic left has assumed that it's not, and that objectives of rough equality and full employment can be achieved within the constraints of capitalist ownership.

In fairness, this was more or less the case in the post-war years (although much of the "commanding heights" of the economy were nationalized then). But this broke down in the 1970s - a fact with which social democrats have never truly got to grips with.

And perhaps they won't - until they start posing the question they have ignored, of whether, perhaps, capitalist ownership is more of an obstacle than they have assumed. I don't know what the answer is here - though I have my suspicions! But if Labour is to be a serious policy-making party, rather than a mere marketing operation, shouldn't it at least ask the question?

December 19, 2012

Depressing immigration attitudes

Sunny draws my attention to the "awful" fact that the public are overwhelmingly hostile (pdf) to immigration. This raises the question: what if anything can be done to change this?

One possibility is to appeal not merely to the facts, but to the evidence of people's own eyes. A poll (pdf) by Ipsos Mori has found that although 76% of people think immigration is a big problem in Britain, only 18% think it a big problem in their own area, and twice as many say it is not a problem at all.

However, several things make me fear that an evidence-based approach won't suffice to change people's minds:

- Hostility to immigration does not come merely from the minority who lose out in the labour market. People from higher social classes and the retired are as opposed to immigration as others. And even in the 60s, when we had as full employment as we're likely to get, there was widespread anti-immigration feeling. This suggests we can't rely upon improving labour market conditions to improve attitudes to immigration.

- There's little hope of attitudes changing as older "bigots" die off. The Yougov poll found that 68% of 18-24 year-olds support the Tories' immigration cap.

- Antipathy to immigration has been pretty stable (in terms of polling if not the violence of its expression) since at least the 1960s. This suggests there are deep long-lasting motives for it; I'd call these cognitive biases such as the status quo and ingroup biases.

- There's an echo mechanism which helps stabilize opinion at a hostile level. Politicians and the media, knowing the public are opposed to immigration, tell them what they want to hear and - a few bromides aside - don't challenge their opinion; one of the many appalling features of "Duffygate" was Gordon Brown's abject failure to challenge Mrs Duffy's hostility to immigration. (The BBC is also guilty here: "impartial" debates about immigration often seem to consist of the two main parties arguing about how to control it.)

All this makes me ambivalent about "calls for a debate" about immigration. Part of me thinks: bring it on - let's talk about the facts. But another part of me thinks that rightists just want to raise the salience of an issue on which public opinion is on their side.

There is, though, a deeper issue here.The fact that public opinion is hugely and stably opposed to immigration suggests that there is a tension between liberty - immigration is an issue of freedom - and democracy.

December 18, 2012

On gender stereotyping

If you want your daughter to become a mathematician, send her to an all-girls school. Research by Marta Favara has found that girls who attend single-sex schools are more likely to choose to study "masculine" subjects such as maths and science than girls who go to mixed school, even controlling for ability:

Attending a sixth form single-sex school alleviates the influence of gender stereotypes for girls. In the absence of gender pressure, gender stereotypes lessen and choices are based mainly on the maximization of their expected monetary pay-off...Single-sex contexts foster less stereotypical behaviours for girls.

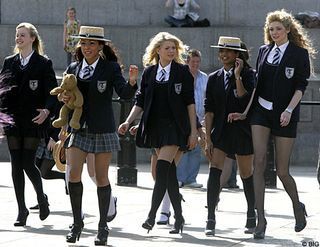

This is probably because of a form of priming effect. Girls who attend mixed schools are surrounded by boys and so become more acutely aware of gender differences than gels at schools like St Trinians, and this leads them to become more feminine.

This is not an isolated finding.It's consistent with Alison Booth's finding that girls from single-sex schools are more competitive - more "masculine" - than ones from mixed schools.And it's consistent with experimental evidence (pdf) which shows how gender differences can arise from priming effects.

I mention this for three reasons.

1. It corroborates Akerlof and Kranton's work, which shows (pdf) how our (self-perceived) identities affect economic outcomes such as career choices.

2. It shows how "nudges" are not just policy levers. Subtle but important influences upon our behaviour are everywhere.

3. It give us another example of how the ideologies that sustain inequality arise inadvertently: studying "girly" subjects tends to lead to lower earnings.The creators of mixed schools had no desire to increase gender stereotypes, but this is what has happened.Unintended consequences are ubiquitous.

December 17, 2012

Divide-and-rule

The Tories are up to their old tricks. In the Times, Tim Montgomerie calls on Cameron to "turn the issue of immigration into an issue of fairness for the working class." He says:

For the people at the bottom of the pile the impact [of immigration] has been enormous...The flipside of cheap nannies, cleaners and painters for the well-to-do in Hampstead and low-cost waiting staff for the hospitality industry is a struggle to make ends meet for hundreds of thousands of low-income British families.

But how "enormous" is enormous? Mr Montgomerie doesn't give us any numbers. The largest reputable estimate of an impact low-skilled wages I've seen comes from Jumana Saleheen and Steve Nickell:

A 10 percentage point rise in the proportion of immigrants working in semi/unskilled services — that is, in care homes, bars, shops, restaurants, cleaning, for example — leads to a 5.2 percent reduction in pay.

However, a 10 percentage point rise is a big rise - a near-doubling: in their data sample, these industries have immigrant proportions of around 12%.

Even if this is right, it does not justify restricting immigration. Insofar as the "well-to-do" gain from immigration, it is instead a case for a more redistributive tax and benefit system, to spread the gains more equitably.

What's more, immigration is not the only - or even main - reason why hundreds of thousands of low-income families are struggling to make ends meet. There's also the recession (since January 2008 real average earnings have fallen 7.6%, a bigger decline than even Nickell and Saleheen's estimate of an immigration effect); the impact of technical change and globalization in reducing the wages and job prospects of the unskilled; and of course the rising power of the capitalist class.

But Mr Montgomerie omits any mention of these. It's rather queer for someone to care so much about the fate of unskilled workers in the context of immigration, and yet be indifferent about the many other threats to their well-being. It's enough to make one suspect that something else is going on.

That something is the same thing that we're seeing in the Tories adverts attacking people "who won't work." It's a crass and largely fact-free exercise at divide-and-rule, an attempt to turn natives against migrants and those in work against those out of work, thus disguising the fact that all four groups have common concerns.

In fact, I fear it's worse than that. The cultivation of animosity to foreigners, and a glorification of virtuous hard-working indigenous people has a whiff of fascism about it.

December 16, 2012

Gay marriage: a case of framing

The issue of gay marriage gives us a nice example of how politial questions get framed. I say this because of something Roger Scruton writes in the Times:

Some of us are troubled by the shallow reasoning that has dominated the political discussions surrounding this move, as though the threadbare idea of equality were enough to settle every question concerning the long-term destiny of mankind.

And both sides of the issue frame it as one of "equal marriage."

But there's another reasonable frame. We can think of permitting gay marriage not as a step change towards equality, but rather as a gradualist move towards slightly greater freedom.

Think of it this way. Over a very wide domain, the state already takes no interest in my choice of marriage partners. It is indifferent to their age (subject only to age of consent laws), ethnicity, psychological compatibility or appearance. Why, then, should it care about the contents of their trousers? Viewed in this frame, permitting gay marriage merely expands the range of characteristics of my marriage partners about which the state doesn't care. It's a small step to greater freedom. We could rename "equal marriage" as "free marriage."

Of course, framing the issue as one of freedom does not clinch the case for permitting gay marriage. Marriage is, as Scruton says, surrounded by social norms. But this runs into other questions: is there really a strong norm against gay marriage? Most people support it, consistent with Nick's view that the public have a "near total disregard for the teachings of the clerics and prelates", which suggests the norm is weak. But even if it were stronger, there'd still be the questions: what good does this norm serve? Why should the norm be embodied in law rather than in public opinion? And why should the law embody this norm rather than other norms against potentially bad marriages, such as to an unsuitable woman I'm temporarily infatuated with?

So, why is the issue so often framed as one of equality rather than freedom? I suspect conservatives have an instinctive aversion to gay marriage, and prefer to rationalize this as a big issue of equality rather a small issue of freedom, because they feel more comfortable opposing equality than opposing freedom. Conversely, campaigners for legalizing gay marriage - being mostly on the left - feel more comfortable with talk of equality.

But my point is merely that the issue can be viewed through more than one frame.

Another thing: there's another frame here - that of tradition versus rationality, but this doesn't lend itself to reasonable discussion, because what is at stake is the value of rationality itself.

December 15, 2012

Inequality: power vs human capital

David Ruccio points to labour's falling share of income in the US and says:

We need to talk much more about profits and who owns capital. And, in addition, who appropriates and distributes the surplus and to whom that surplus is subsequently distributed.

This is like saying a man should put his trousers on before leaving the house.It's good advice, but it shouldn't need saying.

A nice new paper by Amparo Castello-Climent and Rafael Domenech at the University of Valencia supports his point.

They point out that there's no correlation between inequality of human capital and inequality of incomes. This is true across time: since 1950 human capital inequality has fallen in most countries but income inequality hasn't. And it's true across countries; many Asian countries have quite high inequality of educational achievement but low income inequality whilst south America has unequal incomes but relatively equal human capital.

This is a challenge for the neoclassical view that income inequality is due to inequality of marginal productivities.

One might try and rescue the marginal productivity story by arguing that the return to primary education is low and that to university education has risen because of skill-biased technical change, so that a rise in human capital equality because of higher basic skills is compatible with rising inequalities of marginal productivity. However, other research suggests this story isn't true; the returns to basic skills are quite high, and changes in inequality are loosely linked to changes in education.

Instead, the more obvious possible reason for the lack of link between human capital and income equality is simply that inequality reflects not differences in productivity but differences in power which themselves arise from institutional differences.Inequality is higher in south America than in Japan or South Korea simply because south America has extractive institutions which enable a small minority to exploit the masses, whereas Japan and South Korea do not.

Institutional differences in power also help explain another fact: why does the return to university education differ so much (pdf) across European nations of similar income? It is higher in the UK than in Germany or Nordic countries, for example. It's hard to explain this by technical change or globalization, as these factors should have affected countries reasonably similarly. A more plausible possibility, surely, is that institutional factors - the power of capital over labour - allow (some) graduates greater access to the economic surplus in the UK than it allows them in the Nordic countries.

Although I'm speaking here in macroeconomic terms, the point holds at a micro level too. Why did Rebekah Brooks get a £10.9m payoff from Murdoch? It's not because she has obvious greater marginal productivity or technical human capital than the rest of us. It's because (for reasons we needn't consider) she had privileged access to the surplus.

Inequality, then, is better explained by power than by human capital or marginal productivity.

December 13, 2012

WEHT the party of small business?

There's one aspect of Starbucks tax-dodging that hasn't had the attention it should. To see it, ask: who loses when multinationals don't pay tax? The answer is not just the Exchequer, but the small businesses competing with the big firms. The independent cafe owner competing with Starbucks is already at a disadvantage because Starbucks size allows it to bear losses and to buy in bulk. Starbucks' tax-dodging gives it a further edge - because in retaining more of its cash, Starbucks can more easily open new stores, taking custom from the independent cafe. Similarly, independent booksellers who do pay tax are disadvantaged when Amazon doesn't.

You would therefore expect the backlash against multinationals tax-dodging to come not just from lefty moralizers, but from supporters of small businesses.

But I haven't been deafened by such complaints. To those of us whose outlook was formed in the 80s, this is weird. The Tories then claimed to be the party of small business: Thatcher never lost a chance to remind us she was a grocer's daughter.

And, ideologically, Conservatives have alleged that there is an affinity between them and small business. Thatcher claimed that such businesses "embody freedom and independence". And David Willetts wrote in the early 90s that:

Modern conservatism aims to reconcile free markets (which deliver freedom and prosperity) with a recognition of the importance of community (which sustains our values) (Modern Conservativism, p92)

And aren't cafe and bookshop owners pillars of local communities?

Which poses the question. Why, then, aren't today's Tories so angry about the threat to small businesses posed by the multinationals? Surely, many small businesses are threatened more by multinationals' ability to use their tax-dodging to expand than they are by employment protection laws. So why the silence? (It's not just multinationals' tax-dodging where Tories are surprisingly quiet; I got the impression they were equivocal when farmers complained about supermarkets using their buying power to drive prices down.)

It's not because small businesses are less numerous now than they were in Thatcher's day. Quite the opposite. Since 1987, the numbers of self-employed have risen by one-third, much faster than the growth in employment generally. You'd therefore expect politicians to speak more about the interests of independent sole proprietors than they did in the 80s. But it seems they speak less.

This is a puzzle. I mean, it can't be that the Tories were never sincere about being the party of small business, and only ever used such talk as a front for being the party of big business, can it?

* It seems that, in Starbucks' case, tax-dodging has recently been a bad business strategy, but this is because of lefty customers boycotting it, which only emphasizes the puzzle that the right is no longer the party of small business.

December 12, 2012

TV & ideology

Public opinion has long been quite hostile towards a lot of welfare spending: according to the British Social Attitudes survey, only 15% would like to see higher benefits for the unemployed.Might television be partly to blame for such hostility? A new paper by Tanja Hennighausen suggests so.

She studied the attitudes of East Germans in 1990 to the question: Does success in life depend more upon luck than effort? She found that people living in areas where they could watch west German TV were more likely to say success depended upon effort than people who didn't have access to western TV.The effect is quite strong - twice as much so as the impact of being unemployed, for example. She concludes:

Television may affect policy outcomes even if that may not be intended but may just be a byproduct of providing entertainment.

The effect here, though powerful, is quite subtle. In most TV dramas, people are, to a fair degree, masters of their fate. Good things happen (ultimately) to good people and bad ones to bad people, and the good guys usually make it to the end of the series. Sure, this isn't always the case, but exceptions, such as Spooks and American Horror Story, tend to be shocking by their very unusualness. In this way, TV helps strengthen the capitalist ideology that you can succeed if only you try hard enough.

This, though, is not the only evidence that TV promotes individualism. Ben Olken has found (pdf) that in Indonesian villages where TV reception is good, social capital tends to be weaker than in villages where it is poor.

The point here is that the ideology that sustains capitalism doesn't arise merely (or even I suspect mainly) from deliberate attempts by evil capitalists to manipulate the masses. It might be, as Ms Hennighausen says, an unintended byproduct.

The evidence, then, seems to support Gillian Anderson's opinion:

The whole concept of sitting down in front of a TV feels like one of things that’s destroying society as far as I’m concerned.

But then, if you were looking for criticism of Ms Anderson, you've come to the wrong place.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers