Chris Dillow's Blog, page 157

February 14, 2013

The helicopter paradox

I recently suggested that there's a paradox about inheritance tax - that the sort of people who instinctively support it should in fact oppose it, and vice versa. I suspect there's a similar paradox with the debate about helicopter money - those who advocate it should in fact think it'll be little better than other policies, whilst those who should most favour it seem not to do so.

To see what I mean, let's define helicopter money. It does not mean that Sir Mervyn throws £20 notes from a heliopter. Instead, it means that the government hands money to the private sector - by, say, a tax cut or increased investment.It finances this by issuing gilts which are immediately bought by the Bank of England with newly-created base money. Those gilts are then cancelled. A helicopter drop, then, as Simon says, is just a money-financed fiscal expansion. But how does this differ from a bond-financed expansion, in which the government sells gilts to the private sector?

The standard answer* is that the extra supply of gilts reduces their prices and hence raises their yields; in the textbook model, we move up the LM curve. This increases borrowing costs for companies, thus reducing capital spending and so - to some degree - offsetting the fiscal stimulus.

The case for a money- rather than bond-financed fiscal stimulus thus rests upon the response of gilt yields to extra supply. The more gilt yields rise if their supply increases, the better - in terms of macro stimulus - is a money-financed expansion.

Who, then, would we expect to support a money-financed stimulus? Obviously, the sort who think that extra gilt issuance would frighten the markets.

By contrast, the sort of people who think there's huge demand for safe assets - so the government can sell gilts without depressing their prices much - won't see much advantage in a money-financed fiscal expansion over a bond-financed one.

Which brings me to my paradox. This exactly not the division we're seeing. For example, Martin Wolf endorses a helicopter drop, but he has written that "the massive fiscal deficits being run by the UK and US are not...crowding anybody out of the market." But if you believe the latter - as I suspect you should - then a bond-financed expansion is fine and we don't need a helicopter drop.

On the other hand, we'd expect Tories - who want government debt to come down - to favour a helicopter drop. But AFAIK, few do so.

There is, I think, an explanation here. A money-financed fiscal expansion, as Simon and Sir Mervyn agree, tends to raise future inflation. To some this is no problem and might even be a good thing. To others, it is. Perhaps, then, the old division between rightist inflation hawks and leftish/Keynesian inflation doves lingers on**.

* I'm ignoring Ricardian equivalence, as this doesn't seem a live issue now.

** Sir Mervyn and Mark Carney both oppose helicopter drops. This isn't necessarily because they are inflation hawks. It might be because they see the inconsistency between raising future inflation and retaining an inflation target.

February 13, 2013

Beyond hydraulic policy

One of the more significant things Sir Mervyn King said today is this:

There are limits to what can be achieved via general monetary stimulus – in any form – on its own...As time passes, larger and larger doses of stimulus are required.

This won't be a surprise to those who doubt the efficacy of monetary policy when interest rates are around zero - though it might to those advocates of NGDP targets who sometimes give the impression that there's little difference between announcing a target and achieving it.

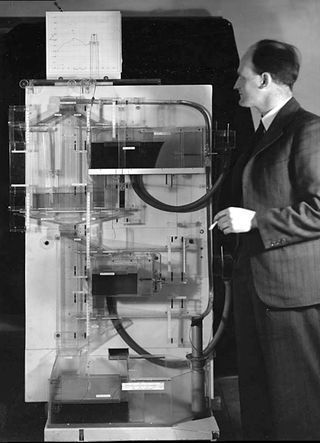

There's a more general point here. King is rejecting "hydraulic macroeconomics" - eombodied in Bill Phillips' Moniac - which believes that pulling policy levers has stable, predictable effects.

Of course, it's not just monetary policy which has variable effects. Fiscal multipliers also vary from time to time and place to place, depending upon whether we are at the zero bound, the extent of credit controls, the exchange rate regime and so on.

Economics is not physics or engineering: there are few if any stable, reliable parameters.

Though all this should be well known, it has implications which I don't think are properly appreciated.

For one thing, it suggests that macroeconomic stabilization is harder to achieve than supposed.If the precise efficacy of monetary policy is unknown, could we rely upon it to atabilize output if an adverse shock were to hit us this year? I doubt it.

If this is the case, it suggests economic policy should have other priorities.

The obvious one is that it should aim at boosting long-run growth through supply-side reforms. Personally, I'm sceptical of this too; long-run growth may be less malleable than supposed.

Instead, there's another alternative. If macroeconomic policy cannot be relied upon to stabilize growth, threre's a case for other means of reducing economic risk - such as a stronger welfare state or macro markets. But there's no popular taste for this. If anything, the opposite. The coalition's desire for smaller government spending and larger exports would - if it is achieved which I suspect it will only half be - tend to increase economic volatility.

However, the issue here goes beyond macroeconomics. If macroeconomic policy is not hydraulic but instead has varying efficacy, mightn't the same be true of other areas of policy, such as health and education where the effectiveness of policy levers could vary with (eg) social norms?

I fear that politicians, being selected for having an optimism about what policy can achieve, under-estimate this problem - until, of course, they have been in office for a while.

February 12, 2013

Rationality vs friendship

Norm returns to a theme of his - of wondering why the anti-war left couldn't and still cannot see that there was a case for overthrowing the fascist Saddam Hussein. I suspect that what's going on here is a common combination of two cognitive biases - groupthink and sampling bias.

The sampling bias is our tendency to forget that the people we associate with are more like us than the general population. Groupthink is the tendency to become overconfident about our beliefs simply because they are echoed by people we like.The combination of these two biases leads us both to over-estimate the prevalence of opinions like our own, and to be overconfident about their validity.

It's not just - or even mainly - the anti-war left that's prone to these biases. Republican pundits who expected Romney to win the presidential election made the same mistakes - though wishful thinking might also have been involved; being surrounded by Republicans led them to under-estimate Obama's support. It's a cliche that Hampstead liberals live in their own bubble. And one reason why chief executives often come across appallingly when interviewed on the radio is that, surrounded by like-minded people, they are unused to having their ideas challenged.

Luckily, there are ways we can counteract these twin biases.

First, for any strong belief you have, ask: what is the strongest case I can make against it?

It's important to do this because the most popular arguments for a particular policy are often mindless. But it doesn't follow that all arguments for them are. For example, the fact that the claim that Saddam had WMD was a lie should not discredit the claim that he was a tyrant we are better off without*. Similarly, just because talk of a structural deficit is drivel, it does not follow that there is no case to be made for fiscal austerity.

Secondly, we should open ourselves up more to opposing views. If you're a rightie, read the Guardian, and if you're a lefty, read the Torygraph. I subscribe to the Spectator but not the New Statesman.

Herein, however, lies a problem. There is a trade-off between inculcating rationality and building friendships. Rationality requires that we seek out people to challenge our worldview, but friendship and community requires that we move among like-minded people. This is another way of corroborating Jon Elster's observation that "the only persons who are capable of taking an unbiased view of the world are the depressed" (Alchemies of the Mind, p299).

Which only goes to show, yet again, the truth of Isaiah Berlin's view that the great goods are mutually incompatible.

* I don't say this to take sides in this debate; the case for or against the Iraq war is a matter of accounting, on which I have insufficient data.

February 11, 2013

The Tamara Ecclestone paradox

The government's otherwise inadequate proposals on funding social care have set me thinking about Tamara Ecclestone.

Their plans involve a proposal, to increase inheritance taxes by freezing the threshold above which tax is paid. The raises the under-explored question of the desirability of such taxes.

The case for them has traditionally rested upon questions of practicality and ethics: how many loopholes does the tax have? Should the state interfere in family life? Is is desireable that a privileged few should get something for nothing?

There is, however, an economic argument for such taxes, highlighted by Wojciech Kopczuk.

He points out (pdf) that if people expect to get a big inheritance, they have less incentive to work, and so an inheritance tax can be optimal to the extent that it raises work incentives. Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have shown (pdf) that this, along with other factors, can generate high optimal inheritance taxes.

This raises a paradox. To see it, ask: who are the sort of people who expect to get big inheritances and so are deterred from working? There are two (extreme) possibilities:

1. The rich have high skills, and such skills are passed onto their children by genes or environment. If this is the case, the economy will lose a lot if the children of the rich are disincentivized from working. We should therefore favour high inheritance taxes as a way of reincentivizing them to work.

2. The children of the rich are airheads, wastrels and no-marks, so it's little loss to the economy if they are out of the labour market. If this is so, the case for high inheritance taxes to motivate them to work is weak.

Which generates my paradox. The sort of people who instinctively oppose inheritance taxes tend, I suspect, to believe the rich pass on skills to their children. But if you believe this, you should favour higher inheritance taxes on economic grounds. On the other hand, those - like me - who viscerally support inheritance taxes tend to think the children of the rich are abominations who can safely be kept out of the labour market. To us, the country would be a better place if George Osborne had been disincentivized from working. But if you believe this, you shouldn't want an inheritance tax that forces the little bastards into work.

The point of this is two-fold. First, there can sometimes (often) be a conflict between rationality and instinct. Secondly, one's beliefs in the fairness of taxes can sometimes sit uncomfortably with one's views about their efficiency.

Another thing: you might object that inheritance taxes are inefficient insofar as they deter parents from working. Maybe, maybe not. But this doesn't, I think, weaken my paradox.

February 10, 2013

Some benefits of religion

Francis Sedgemore says:

Atheists will never “call off the faith wars”. We are in this battle to the end of religion, which poisons everything.

I fear this overstates things. There's lots of research - much of it summarized here (pdf) and here (pdf) to suggest that religion has some positive effects. For example, it is associated with increased trust and lower crime (pdf), and - at least amongst protestants and jews - with higher education and labour supply. For these reasons, it's quite possible that religious beliefs - if not (pdf) actual church attendance - are conducive to prosperity.

What's more, there's pretty good evidence that religious belief is associated - on average and with exceptions naturally - with higher subjective well-being, not least because it cushions us against adverse events.

Of course, you don't have to look far for evidence that religion also has horrible effects. But it is surely absurdly unscientific to think that Boko Haram or the Taleban are typical of religious observers.

You might object to this that religious belief is just irrational. But it doesn't follow that the defeat of religion would mean the triumph of reason. You only have to look at Comment is Free to see that people have an infinite number of ways of being silly without believing in sky fairies. As G.K. Chesterton said, when people stop believing in God they don't believe in nothing but in anything.

I cannot, therefore, side with some of my fellow atheists in regarding religion as wholly bad. Indeed, I suspect it's unscientific to do so. Maybe, all things considered, it is a net bad, but the Hayekian in me thinks it impossible for anyone to construct a fully accurate balance sheet of all its costs and benefits.

Which brings me to a paradox. My personal attitude to the content of religion was formed by reading Bertrand Russell's Why I am not a Christian as a teenager; I don't think Dawkins or Hitchins add much to this. But this is moderated by the research suggesting that - at least here in the west - religion has some favourable social effects. I'm puzzled, then, that the "culture wars" should be more intense now than at any time in my life. I suspect there are two reasons for this.

One is a version of the halo effect. People tend to think that if religion is bad in one respect - "it's irrational" - it must be bad in many others. But it ain't necessarily so. (Believers, of course, are also prone to this error.)

Secondly, we live in an age of ego, and of fragile ego at that. The demand that religion die out, or that it spread, amounts to little more than the demand that people be more like me, me, me.

February 9, 2013

How the wage squeeze helps the Tories

Is the stagnation in productivity and squeeze in real wages good for the Tories? I ask because of a fact pointed out by Andrew Pickering and colleages in a new paper - that there's a strong positive correlation in developed economies between the share of wages in GDP and the size of government. Both increased in most OECD economies between the 1960s and 1980s, and both have fallen since in most.

You might think this is because both are counter-cyclical; in recessions, the wage share and size of government both increase. However, Pickering and colleages point out that the correlation holds even controlling for the size of the output gap, which suggests there's more than mere cyclicality going on.

There are two things here.

One, which they stress, is that the wage share is a measure of the relative cost of government. Because many government services are labour-intensive, falling wages reduce the relative cost of government, thus allowing the state to shrink.

In this context, falling productivity in the private sector actually helps the Tories because it puts Baumol's cost disease into reverse. When productivity grows faster in the private sector than public, the relative cost of public services rises, tending to increase the size of government. But private sector productivity is now falling whilst that in the public sector is rising; the data (if you believe them) shows that government output has risen 3.7% in the last two years whilst public sector jobs have fallen. This is reducing the relative cost of government, thus making it easier to shrink the state.

You might think this is a relatively benign thing. If it's cheaper to provide education and health services, a fall in government spending as a share of GDP is no problem.

True. But I fear there might be another factor at play, to the detriment of social democrats.

It's that the demand for government might be income-elastic. If you're struggling to pay the gas bill or to buy petrol to get to work, you'll be more opposed to paying tax (and be less pro-social) than if you're more comfortable.

In this regard, the "squeezed middle" might be no friend to social democratic objectives.

Perhaps, then, falling real wages are more helpful for the Tories' cause than generally supposed.

Another thing: the share of wages in UK GDP has been quite stable lately. But I don't think this affects my point - not least because, if we do get a recovery in GDP whilst high unemployment holds down wages, the wage share will fall.

February 8, 2013

Pensioners, voting & interests

Mark Carney says, correctly, that economic policy has made things "extremely difficult" for pensioners and savers.This highlights the fact that many people don't vote in their own rational self-interest.

What I mean is that there is an obvious alternative to the current economic policy. A looser fiscal policy would benefit pensioners by raising interest rates. This isn't because bond markets would take fright, but simply because such a policy, in tending to strengthen the economy, would reduce the need for QE, reduce investors' demand for safe assets, and bring forward the time when short-term rates would rise. In this way, annuity rates and savings rates would be higher, to the benefit of pensioners and near-pensioners.

You'd expect, therefore, older people to be more hostile to present policy than younger ones - because whilst many older folk have savings and are hurt by a tight fiscal/loose monetary policy mix, younger people with mortgages gain from such a mix.

But this is not so. A recent poll (pdf) found that over-60s split 37-34 in favour of Tories over Labour whilst 25%-49% year-olds split 33%-47%. And slightly more over-60s think the government is managing the economy well than do 25-49 year-olds: 35% against 31%.

It seems, then, that the government's attack upon the living standards of older people has not provoked the sort of hostility which you'd expect from a rational selfish electorate. (Sure, some older richer people are switching to UKIP - but I'm not sure this undermines my point.)

Why not? One reason is that narrow economics isn't everything; people support political parties for all sorts of reasons.

But I suspect something else is at work - a corrollary of the availablity heuristic.

Although the link between fiscal austerity and nugatory savings rates is obvious to economists, and to anyone else to whom it is pointed out, I suspect it is not so to many voters. And the Labour party is not drawing attention to it: Ed Balls is not touring the country saying "my policy would raise interest rates" even though, if it is any use at all, it would do so. The fact that the Tories are exacerbating the squeeze on many pensioners' incomes is, therefore, simply not available or salient to many voters. And so it is underweighted in their minds.This helps sustain Tory support among older folk.

It's a commonplace - to we Marxists at least - that ideology prevents (some, many) workers from seeing where their interests lie. But maybe ideology doesn't distort only workers' perceptions.

February 7, 2013

Institutions, culture & change

How do you change the culture of an organization or society? I ask because of Robert Francis's claim that "a fundamental culture change is needed" in the NHS.

This runs into the problem described by Phil Hammond in the Times - that the Kennedy report into excessive deaths of babies at Bristol Royal Infirmary 12 years ago made similar recommendations to Francis, which do not seem to have been heeded. Merely recommending change, therefore, is not sufficient says Hammond:

We've learnt that large, distant regulators and centralized management don't work..Time for a bottom-up revolution rather than more top-down pressure.

You might think I'd agree. But I'm not sure. Mere institutional change on its own isn't sufficient to change things for the better, as Acemoglu and Robinson say in Why Nations Fail:

There should be no presumption that any critical juncture will lead to a successful political revolution or to change for the better. History is full of examples of revolutions and radical movements replacing one tyranny with another (p111).

For example, the collapse of Tsarism didn't end Russians' desire for a strong leader, and after decolonization African leaders merely continued the exploitative practices of their colonial predecessors.

There's a reason for this. Institutions shape culture, and the imprint of institutions lasts after the institutions themselves disappear.

This problem afflicts individual organizations as well as societies. Jeffrey Nielsen has described how hierarchical organizations breed "rank-based thinking" and demotivated employees; in saying this, he's channelling Tocqueville, who argued that democracy's great virtue was that it "spreads throughout the body social a restless activity, a superabundant force, and energy never found elsewhere."

Now, if a man has been hit by a bus you cannot restore him to health merely by reversing the bus. Institutional change doesn't immediately create the sort of energy which motivates individual workers to challenge bad practice. Francis calls for "openness, transparency and candour throughout the system". But it doesn't follow that open structures will create an open culture. Nurses and junior doctors who have become used to not challenging managers and consultants might remain deferential.

Bosses are fond of the cliche "my door is always open." But they don't get a heavy footfall.

Marx was, arguably, awake to this problem. A precondition for successful revolution, he thought, was a change in working class "culture":

Where the working class is not yet far enough advanced in its organisation to undertake a decisive campaign against the collective power, i.e., the political power of the ruling classes, it must at any rate be trained for this by continual agitation against and a hostile attitude towards the policy of the ruling classes.

Herein, though, lies the problem. Insofar as institutions shape culture, the scope for cultural change is limited. At yet without cultural change, institutional change won't yield the results people hope for.

The question for anyone hoping to change the culture of an organization is the same it has been for Marxists for decades: is this an insuperable impasse or not?

February 6, 2013

Welfare spending & government borrowing

Does social security spending add to government borrowing? I'm prompted to ask by Daniel Furr's claim, inspired by the IFS's forecast (pdf) of rising social security spending in coming years, that any government will have to cut such spending if it is to reduce borrowing.

I ask because it's not obvious that welfare spending does add to borrowing. Think about the circular flow of income. Let's say every pound a doleite gets is spent at Tesco. A cut in the dole then means lower revenues and profits for Tesco and its suppliers - which means they pay less tax - and lower employment at such establishments, which means less income tax and more welfare spending.

It's not intuitively obvious from this that cuts in welfare spending would reduce government borrowing.

Let's formalize this intuition a little. Government borrowing, by definition, must equal the net lending of the domestic private sector and foreigners. A cut in welfare spending, then, can only reduce government borrowing if it cuts the net lending (saving) of foreigners or the private sector. How might this happen?

One obvious route is that a cut in welfare reduces spending on imports and so reduces foreigners' net lending, our current account deficit. But I suspect the marginal propensity to import from of welfare spending is small, so this is only part of the story.

Another possibility is that welfare cuts cause recipients to borrow more. From the point of view of cutting the deficit, the claim that the "bedroom tax" will plunge people into debt is not a bug but a feature. It's only if individuals get into debt that the government can get out of it. This is an accounting identity.

There are, however, other possibilities. If the welfare state gets meaner, people in work might save more for fear that the state won't support them so much if they lose their job. And it's possible - though not certain - that weaker automatic stabilizers will make businesses more fearful of economic volatility and so less inclined to invest.

In theory, then, it's not clear that benefit cuts would reduce borrowing. But what of evidence?

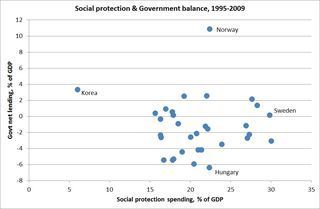

My chart provides some. It plots spending on social protection in 31 OECD countries for which we have data against government net lending. I'm averaging over the years 1995-2009 to smooth out cyclical fluctuations.

The chart shows zero correlation between the two. Yes, Korea had a small wlefare state and Budget surplus. But equally, Sweden's generous welfare state was accompanied by a small budget surplus in this period, whilst the meaner welfare states of Japan, Italy, the US and UK all had deficits.

Now a zero correlation means zero; there's no evidence here that a more generous welfare state must improve the government finances. But equally, this evidence is consistent with the claim that you cannot cut government borrowing by cutting welfare spending.

By all means, argue that we need welfare reform on other grounds - say to improve work incentives. But let's not kid ourselves it's a surefire way of reducing government borrowing.

February 5, 2013

Gay marriage & the conservative disposition

Charles Moore's hapless attempt on the Today programme to oppose gay marriage has been widely decried. But I suspect that, underneath his waffle, there is a useful perspective which is in danger of being forgotten.

Charles was trying to express the classical conservative disposition. This - associated with Burke, Oakeshott and partially Hayek - is sceptical about the powers of individual reason. Instead, it believes that traditions embody more wisdom than we know, and that deviating from these traditions can lead to unforeseeable effects. As Oakeshott said (pdf):

The total change is always more extensive than the change designed; and the whole of what is entailed can neither be foreseen nor circumscribed.

In this context, Moore's incoherence was not an individual failing, but a necessary consequence of his ideological position. If you believe that individual rationality is a weak tool and that consequences cannot be fully foreseen, then you cannot articulate your position well because - ex hypothesi - you cannot know the costs and benefits of social change.

When Norm says there are no reasoned arguments against gay marriage, he's right. But to conservatives like Moore, this tells us about the limits of reason, not the merits of gay marriage.

Herein, I think, lies a difference between what Hopi calls social conservatives and metropolitan liberals. Social conservatives such as Moore are sceptical about rationality and cleave to tradition; liberals are more rationalist.

Personally, I have sympathy for this conservative disposition. The cognitive biases programme has taught us that rationality is indeed a weak tool, and society is too complex to be fully understood by any single mind.

However, I have less sympathy for its application in this this case, for two reasons.

1. The case for legalizing single-sex marriage is an intrinsic one; the move embodies important values of equality and freedom. If you want to claim that there are costs of such a move sufficiently large to offset these intrinsic values, you should at least give us some clue as to what they might be.

2. Many of the conservatives who are so opposed to gay marriage have been quite relaxed about other big social changes of recent decades such as the collapse of trades unions, globalization and the growing power and wealth of top managers. (And others might add that they are keen to discard the traditions surrounding the welfare state and NHS). That the conservative disposition should have deserted them on these issues makes me fear that they are not coherent thinkers but merely bigots who hate people who are not like themselves, such as gays and workers.

But here's my worry.The conservative disposition is a valuable intellectual tradition. It would be a great shame if it were discredited by its association with anti-gay bigotry.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers