Chris Dillow's Blog, page 155

March 6, 2013

Rational short-termism

The Labour-commissioned Cox report (pdf) argues that short-termism is widespread, and a disincentive to invest and develop new products.However, I fear it under-rates the possibility that short-termism is often rational.

The problem here is one of uncertainty, in the sense of unknown unknowns.Think of any company you know reasonably well. On a short-term horizon - one or two years - you probably have a fair idea of its SWOTs or five forces, or any other way of analysing the firms' prospects.But on a long-term horizon - ten or 20 years - you don't have a clue, not least because for very many businesses it's impossible to forecast whether they'll be brought low by technical change (which by nature is unpredictable at long horizons) or bad management. For a long time Polaroid seemed a sound company, until digital cameras came along; Nokia was doing OK until the iPhone appeared; RBS and GEC did well for years until bad takeovers and strategy killed them. And so on.

Company death rates are high, and their chances of dying can change unpredictably.Whereas risk is roughly quantifiable - under reasonable assumptions it increases with the square root of time - uncertainty is not. Faced with massive uncertainty, it is surely reasonable for investors not to want to commit to long-term investment.

In fact, there's one piece of evidence which suggests that, far from being too short-termism, equity investors haven't been short-termist enough. This is that value stocks - generally, those which offer short-term cashflows - have tended to out-perform glamour ones, which claim to offer growth. This suggests that investors have often been too long-termist, paying for future growth which hasn't materialized.

There are two possible objections to this which I don't think are convincing.

"Short-termism isn't ubiquitous: look at much of Asia." I suspect, however, that insofar as private (as opposed to state) investors there are long-termists, it's because uncertainty is mitigated by the optimism bias; in a fast-growing economy, animal spririts improve.

"Warren Buffett has succeeded by taking long-term investments." True. But they have been in companies which have good short-term cashflows and which can be monitored by short-term results. Buffett tends not to invest in startups or "growth" stories.

I don't say all this to rubbish the Cox report. Instead, it is to suggest that policies to encourage long-termism should be seen another example of anti-nudge; it can sometimes be a good idea to encourage irrationality. The best way to get finance flowing to new and small businesses is to have big dose of irrational exuberance.

March 5, 2013

Bonuses, institutions, culture

One of the advantages of growing old and bitter is that I remember things which our unhistorical managerialist class forget. Reading attempts to defend bonuses reminded me of this.

The thing is, the City has always paid bonuses, originally for reasons more intelligent than Ms Leadsom thinks. Stockbrokers and merchant banks used to pay them simply because their revenues were volatile - being dependent upon M&A activity and share prices and turnover - and so they needed a flexible cost base. Variable bonuses were a better way of achieving such flexibility than regular hiring and firings.Broking firms were practicing the share economy long before Martin Weitzman and James Meade thought of it.

What such bonuses were not, however, were "incentives." I doubt if many partners were daft enough to think that money alone was an incentive. They used other methods as well. One was direct oversight. Business owners worked alongside employees; in my first job at a middling sized brokers, graduate trainees sat a few feet from senior partners. And on top of this there were social norms, the threat of being ostracised socially and economically if one misbehaved and - to be honest - family ties and nepotism. These restraints upon poor performance have (largely) disappeared now.

In this sense, investment bankers' bonuses are a curious example of path dependency. They have continued even though the nature of their business in other respects has completely changed.

The problem is that whereas they were once a way of stabilizing businesses, they have now become a force for destabilizing them - as they incentivized bad risk-taking - and a means whereby a powerful few extract rent from taxpayers and shareholders, under the cloak of ideological guff about incentives.

You might object here that I'm romanticizing the old broking firms. Maybe. But many of them survived for decades, so they were doing something right. And if what I've described is an ideal type, then so too is the neoliberal notion of homo economicus, crudely motivated only by the cash nexus.

My point here is a simple one. There's nothing intrinsically wrong with bonuses. The problem with banks is that the institutional and cultural framework in which they made sense has disappeared. And simplistic talk of incentives and "rewarding success" ignores this.

March 4, 2013

Sterling, profits & mechanisms

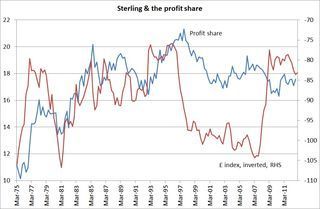

There's one point raised by sterling's fall this year which deserves more attention than it's had - it's that sometimes (often!) quite powerful correlations can break down.

My chart shows what I mean. It plots the share of profits in GDP against the inverse of sterling's trade-weighted index. You can see that from the mid-70s to the mid-90s, there was a close link between the two. A weak pound raised the profit share, and a strong pound cut it. There are good reasons why this should be:

- a fall in the pound helps insulate domestic firms from foreign competition, thus raising their monopoly power and hence allowing them to mark up prices more.

- higher import costs are seen as a fair (pdf) reason for a firm to raise prices.

- exporters who price to market must cut sterling prices of exports when sterling rises, thus suffering a margin squeeze, but can raise margins when sterling falls.

However, this relationship broke down in the late 90s. Sterling's rise then did not squeeze profits as much as you'd expect from past behaviour.

This might be partly because the supply of labour from emerging markets shifted the balance of class power in favour of capital then. But this is unlikely to be the whole story, because sterling's slump in 2008 did not much raise profit margins. Instead, I suspect what's going on is a change in the nature of international trade. A lot of trade now occurs firms, as multinationals (pdf) ship in components from their overseas branches, sometimes at shadow rather than market prices.This makes prices, and hence income shares, less responsive to exchange rates.

The precise reasons for the change, however, aren't really my point. Instead, I merely want to point out that even strong empirical relationships with sound theoretical support can sometimes break down.This is why the study of economics must be a study of mechanisms - which are often local and temporary - rather than of apparent statistical regularities.

* Strictly speaking, I should be using the real rather than nominal exchange rate, but I doubt doing so would make much difference.

March 3, 2013

On financial balances

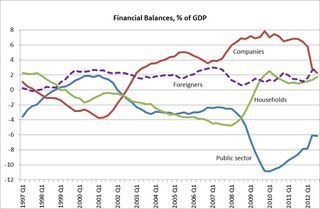

Some readers have expressed bemusement at my claim in an earlier post that the only genuine deficit reduction policies are those which stimulate private sector investment and/or reduce their savings.I should expand.

Start from a trivial identity - that every pound someone borrows is a pound that someone else lends. This means that if one sector of the economy is a borrower, another must be a net lender - that is, its savings must exceed its investment.

My chart shows the net lending of the four sectors of the economy*. The most important point here is the negative correlation between public sector and companies' net lending. When companies were net borrowers in 1999-2001 the government ran a surplus, but corporate net lending in recent years has been associated with government borrowing.

But what's the direction of causality? Is government borrowing causing companies to be net lenders, or vice versa? In theory, government borrowing can depress firms' capital spending - and hence cause it to save more than it invests. But the mechanisms whereby it does so don't seem to operate now. For example:

- Financial crowding out. In this, government borrowing raises interest rates, which deters companies from investing. We know this hasn't happened, because index-linked gilt yields are now negative, and in fact were trending downwards ever since the early 00s when the government became a net borrower.

- Resource crowding out. It's possible that if the government is spending and borrowing heavily it is employing so many workers and materials that companies simply can't get the resouces they need to invest. It should be obvious that this isn't relevant today. And as there were four million unemployed even at the low point in 2005, I doubt it was relevant before the crisis.

- Ricardian equivalence. The idea here is that government borrowing means higher future taxes, and the private sector saves more in anticipation of that burden. This theory, though, runs into several problems, such as: why do people expect taxes to rise rather than public spending to fall? And why, before the crisis, did companies increase saving in anticipation of taxes rising for them, whilst households were saving less, presumably in anticipation of falling taxes?

Given these issues, I suspect the causality runs the other way. Before the crisis, foreigners were net savers, because they were building up FX reserves after the 1990s Asian currency crises, because oil exporters couldn't quickly reinvest oil revenues, and partly because of a lack of a welfare state in China. At the same time, a dearth of investment opportunities caused companies to save rather than invest. These savings caused interest rates to fall, helping to cause a housing boom and net borrowing by households. It also caused governments to borrow more, partly because tax revenues were weak, partly because low interest rates signaled that borrowing was cheap, and partly because weak private capital spending led to the belief that a Keynesian stimulus was necessary.

Since the crisis, though, households have joined companies and foreigners in being net lenders as the housing bubble burst. With those three sectors all being lenders, the government must be a borrower. In more conventional terms, the reluctance of foreigners, households and companies to spend has created a weak economy and hence low tax revenues and the need for counter-cyclical spending.

Which brings me to where I started. The government's deficit can only fall if the other sectors reduce their net lending.

In normal times, fiscal austerity might achieve this by reducing interest rates and thus stimulating private investment. But with interest rates already below zero in real terms, these are not normal times. Osborne thought austerity "will have a positive impact through greater certainty and confidence about the future" - that higher confidence would stimulate private investment. But this hasn't happened so far.

So what policies might reduce private sector net lending? Policies such as the Funding for Lending Scheme, aimed at boosting borrowing, are intended to do so, as is QE. I suspect that the passage of time would also do so; an easing of the euro crisis and a need to replace worn-out capital will eventually boost investment.

But my point here isn't to advocate specific policies, but to merely describe the problem. The problem is that the government has less control over its finances than politicians pretend.

* Four quarter rolling totals. Don't read much into the fall in the corporate surplus recently - it's affected by the transfer of the Royal Mail pension fund.

March 2, 2013

Everybody hates a tourist

In the Times (£), someone says:

For me there's no doubt that the Berlin years were far and away Bowie's best period.

This might seem am almost tenable opinion. It's not, because it's expressed by the Rt Hon Nicholas Clegg. He has no right to like Bowie.

I say this because a common strand in Bowie's career - from his long-hair activism through Ziggy, the Thin White Duke and the Berlin period to his rejection of a knighthood has been his presentation of himeself as an alienated outsider. This is why his fans have been predominantly geeks, gays and artists - the sort of people who were unpopular at school. Clegg, being the head prefect type, has no place in this crowd. As Johnny Marr said about Cameron's liking of the Smiths in the greatest interview ever on the Today programme, "We're not his kind of people."

What Clegg and Cameron are doing here - and Osborne in liking Billy Bragg - is something which reached its apogee in Emily's notorious exchange with Charley in Big Brother 8. They are all so arrogant, and so lacking in self-awareness that they can't see that there are things they'll never properly understand, that some things are closed to them.

Everybody hates a tourist, especially one who thinks it's all such a laugh. Just as I have no right to opinions on polo ponies and skiing holidays, so Clegg and Cameron have no right to Bowie or the Smiths.

I'm invoking here Polanyi's theory of tacit knowledge. Music is not just one note after another. It carries a freight of cultural meanings which are often understood only viscerally - hence the cliche that talking or writing about music is like dancing about architecture. And our backgrounds can prevent us from fully understanding some of these meanings.

You might object that I'm being illiberal here. I'm not sure. There's an illiberal strand in Clegg and Cameron's belief that they have a right to an opinion on everything. It tends naturally towards interventionist government. I'll concede that Clegg is less of a nanny statist than many Tories or Labourites. But his talk of welfare "dependency" and support for press regulation betoken an imperialist mindset.

And, of course, the same arrogant sense of entitlement that cause Cameron and Clegg to think they can like the Smiths and Bowie is what gives them the belief that they are equipped to govern us.

March 1, 2013

Labour's fiscal debate

The debate about what Labour's fiscal policy should be seems to be hotting up. In this, a large part of me sides with Hopi's fiscal conservatism.

You might object that such conservatism - insofar as it is directed at reducing the deficit - is dishonest. Basic national accounts arithmetic tells us that government borrowing will fall if and only if private sector net lending falls. This means that the only genuine deficit reduction policies are those which stimulate private sector investment and/or reduce their savings. Whilst some of Hopi's proposals (an industrial bank?) might do this, it's not clear that, taken together, they would all greatly do so.

But there's a place for dishonesty in politics. If the next election campaign is anything like its predecessors, every footling Labour policy proposal will be met with the question: "where will the money come from?" Whilst Keynesians have an intelligent answer to this, fiscal conservatives have a simple one, understandable by even the densest journalist. When you're faced with a mad dog, you don't reason with it, but throw it a bone.

However, fiscal conservatism doesn't just have low campaigning merits. There's another case for it, even if we leave aside the arguable possibility that intelligent cuts in government consumption might promote long-run growth. I'm thinking here of its impact upon tax morale.If people believe tax-payers' money is being wasted, they'll be loath to pay tax and so anti-statist ideology will grow. If, however, they see a state that's careful about spending, hostility to higher taxes will diminish, at least a little. In this sense, short-term fiscal conservatism might create social norms more supportive of social democracy.Perhaps, then, Hopi is more right that he realizes when he says:

Holding down spending in the public sector...[is] the only way to build an economy that could support a superb public sector in many years to come.

On the other hand, I have three quibbles with him.

First, I'm not sure whether more years of a squeeze on public sector pay are feasible. The problem here isn't just a "pay peanuts, get monkeys" one, but of gift exchange. Squeezing pay risks eroding the goodwill that has caused public sector workers to do thousands of hours of unpaid work, thus eroding the efficiency of public services.

Secondly, if I read him aright, Hopi wants a shift from public consumption to public investment. Over time, this would tend to increase macroeconomic volatility pretty much arithmetically, by shrinking the size of an automatic stabilizer. Yes, fluctuations in public investment can in theory stabilize growth - but only if governments see recessions coming and so raise investment accordingly, and governments don't have this foresight and aren't going to get it.

Thirdly, and most importantly, unless there's an economic miracle, Labour will enter the next election with mass unemployment. Shifting spending from low- to high-multiplier areas will be nothing like sufficient to tackle this. The challenge for fiscal conservatives, then, is how to combine fiscal austerity with job creation?

February 28, 2013

Rennard's lesson

The Rennard affair sends an important message about politics - one which will be ignored.

So far, the allegations against him seem mild. We're not talking Jimmy Savile or Julian Assange here, but the sort of tiresome groper which any woman with a backbone has long learnt to cope with.

Except that is, for one thing. His main accuser, Susan, says:

I possibly could have knocked my chances of any future success within the party by having said no...

This is a man with an almighty amount of power. At the time he held the purse-strings for any winnable seat, and he could choose which were the starred seats and advise other federal bodies which should be the starred seats.So this was a man who could control your future.

The issue here, then, is not sex, nor crime, but power.If these allegations are correct, it vindicates Lord Acton's famous saying:

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority, still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority.

This isn't always a wholly bad thing. One message of Lincoln is that even decent men must sometimes use unpleasant means to achieve worthy ends. But it does pose the question: wouldn't it be remarkable if the only way in which politicians abuse power is to try and get their leg over?

There's another question here. Why was Susan, and presumably women like her, at all surprised by this? It's surely astonishingly naive to think that power will be clean and decent.

One possibility is that they were prone to the optimism bias that afflicts most people entering politics. Another is that they were blinded by tribalism; the misuse of power is something "their side" does, not "ours". This fails to see that the division that matters is not between parties, but between the powerful and the powerless.

Herein, then, lies the big message of the Rennard affair. It's not just about how power can be subtly but insidiously abused, but about how people can try to enter politics whilst being oblivious to this.

I don't expect this message to be noticed, because real power consists in being able to disguise the fact that it is being exercised.The lesson of this affair will not be learned.

February 27, 2013

Happiness vs options

Since it was proposed in the 1970s, many economists have been sceptical of the Easterlin paradox, the claim that rising GDP doesn't increase happiness. Some of the scepticism - which Easterlin himself still rejects - is based upon the data, although this still seems to show that happiness increases only slightly with incomes. I suspect, though, that it is also motivated by a discomfort at the apparent implication of the paradox, which is that aggregate incomes don't (much) increase happiness because, as researchers such as Sheena Iyengar and Christopher Hsee has suggested, the increased choice that comes with higher incomes either demotivates (pdf) folk or causes them to choose badly (pdf).

However, a new paper by Katherine Guthrie and Jan Sokolowsky point out that this implication need not be true.They show that increased wealth and choice might not increase happiness even if people are rational utility maximizers.

Imagine a cinema opens in a dull town. Some people choose to go, others don't. Those who go experience an increase in utility - they would not go otherwise - whilst those who don't experience the same utility as before. Surely, then, happiness has increased.

Not necessarily. Utility is not the same as happiness. Cinema-goers might feel discontent or guilt if they feel they should be working or looking after the children instead. And non-goers might also feel unhappier at work because they think: "I could be at the pictures instead." Guthrie and Sokolow say: "An expanding choice set off�ers opportunity to increase one's utility, but it also evokes rising discontentment."

We don't, therefore, need to assume people are irrational to believe in the Easterlin paradox - the mere fact that they are aware of opportunity costs can do so.

This theory is consistent with (at least) five findings of happiness research:

- Well-paid workers aren't happier in their work than lower-paid ones. This is odd because better-paid jobs are generally nicer. One explanation is that well-paid people have more valuable alternatives; a job that gets you off a crime-ridden housing estate might be no bad thing, but one that gets you away from the golf course is.

- American women have become less happy (pdf) over time. This might be precisely because their options have increased. The career woman feels bad about leaving her kids, whilst the home-maker regrets abandoning her career, whereas Betty Drapers in the 60s never had this choice and so never suffered the higher opportunity cost of not working.

- Well-being declines in middle-age. This could be because we 40-somethings have more options than younger or older folk, and so are more discomforted by having to give them up.

- Commuters are unhappy. This is because they're aware they could be either at home or drinking with workmates.

- Happiness comes from "flow" - losing ourselves in an activity. One reason for this is that when we immerse ourselves in something, we lose awareness of the other things we might be doing, whereas when we are less engaged (for example when watching TV) we are aware of those opportunity costs.

Perhaps, then, the Easterlin paradox - even if it is true - is entirely consistent with rational utility maximization.

February 26, 2013

Chesterton, & inflation

You can now buy the complete works of G.K.Chesterton for £1.97. A few years ago, they would probably have cost hundreds of pounds and lots of effort. I say this as a counterweight to the Telegraph's claim (via) that the cost of everyday goods has "rocketed" since 1982.

True, many such goods have. So much so, in fact, that in some cases they've outstripped wages. Back in 1982, the average pre-tax weekly wage would have bought 148 pints of lager. Today, it buys 146.

And yet the works of Chesterton aren't wholly atypical either. Back in 1982 no money would have bought you a Playstation or iPod. Their prices have fallen from infinity to affordable - that's an infinite rate of deflation. And things we paid for back then, such as some newspapers and music, are now free. Again, massive deflation.

All this should seem trivial. But it has some under-rated implications.

First, such huge changes in relative prices make it impossible to calculate long-run inflation rates accurately. There's no such thing as a "true" inflation rate. How do you compare the prices of goods that exist today with the prices of goods that didn't exist 30 years ago?

Paradoxically - given that he's considered the father of macroeconomics - Maynard Keynes was more aware of this than this followers.The concept of a general price level, he wrote, is "vague and non-quantitative" and "very unsatisfactory for the purposes of a causal analysis": "two incommensurable collections of miscellaneous objects cannot in themselves provide the material for a quantitative analysis."

Secondly, insofar as people think about the general price level, the availability heuristic can lead them to over-estimate its rate of increase. We buy beer, food and petrol every week and so their price rises loom large in our mind. But we buy books and gadgets only occasionally and so their deflation rate is less salient. This could generate a bias to exaggerate overall inflation.

Thirdly, the general price level is that faced by an average consumer. But many of us aren't average. If you spend less than average on deflation-prone goods, and more on those whose prices rise over time, the cost of living for you might rise more than CPI inflation rates would suggest. For this reason, it is possible - only possible, as there are other factors at play (pdf) - that uprating welfare benefits in line with the CPI represents, in effect, a cut in benefit in real terms.

Fourthly, the fact that the price of technology has collapsed relative to (say) beer over the last 30 years is not just a technical fact about relative prices, but a cause of social change; people respond to incentives, remember. Some of this change might be good - if, say, video games have reduced crime. Other aspects of it, however, might be more ambiguous. I fear (this is just a hypothesis) the decline of pub-going and rise of social networking might be contributing to a hollowing out of the social sphere, in which weak ties - those between neighbours - weaken whilst stronger ties (those between like-minded folk) strengthen. In this sense, worrying about the precise inflation rate is missing the point of what price changes do.

February 25, 2013

Trend growth

Moody's decision to cut the government's credit rating because of "continuing weakness in the UK's medium-term growth outlook" will, no doubt, focus attention upon the need to raise our trend growth rate.

Doing so, however, might be very tricky.

To see my point, start from the fact that the economy shrank slightly last year. Does this mean our economy is in trend decline? Probably not. More likely, 2012 was just an unusually bad year. But even if we take many years together, it's quite possible that we'll over-sample bad years (or good) and so get a biased measure of trend growth. To reflect this problem, we should measure the standard error of growth. In its simplest form, we do so simply by dividing the standard deviation of growth rates in our sample by the square root of the number of years*.

My chart does this for each 20-year period since 1831; I'm using Bank of England data, updated by the ONS. The two lines show trend growth plus and minus one standard error. Roughly speaking, we can be two-thirds confident that trend growth in any 20-year period was somewhere between these two lines.

Which brings me to the point. Once we allow for this standard error, trend growth doesn't change much. In fact, except for a period to the mid-30s (which covered the post-war slump and Great Depression), it's quite possible that trend growth has never moved much from around 2%.

In other words, whether we have free markets, post-war social democracy or post-Thatcherite neoliberalism, trend growth might be much the same. Neither Victorian virtues of thrift and hard work (and hypocrisy) nor "dependency culture" much affected growth.

I'm not doing anything odd or original here. I'm just making the same point in time-series form as John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson did in cross-country form when they concluded:

There are few, if any, feasible policies available that have a significant effect on long run growth rates.

It is possible that this is due to luck. Maybe good microeconomic policies have been swamped by bad macroeconomic times and vice versa. Perhaps the interventionist policies of the post-war era were bad for growth, but this was offset by an unusually favourable macro climate, whilst Thatcherite deregulation might have raised growth were it not that bad macro policy gave us two recessions.

Nevertheless, the data suggest that we should be very sceptical of the chances of improving our trend growth rate. Of course, many of the policies recommended by the LSE's Growth Commission - such as better education and infrastructure - are good ideas.But history suggests they are unlikely to have a noticeable effect upon trend growth.

* This method assumes that the observations are independent of each other. This isn't quite true in these data, as the serial correlation between annual growth rates since 1831 has been 0.28. I don't think this overturns my basic point.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers