Chris Dillow's Blog, page 152

April 10, 2013

Can there be a left Thatcher?

The retrospectives on Thatcher's political life pose a question that's central to left politics today: to what extent can individual politicians transform the economy through their own will and ideology, and to what extent must they operate within the parameters set by capitalist economics? Peter Oborne asserts the "great woman" theory, but I suspect instead that she succeeded because she had the strong tailwinds of ideology and capitalism on her side.

This question matters because it determines our attitude to the Labour leadership today. If you think a "left Thatcher" is possible, then you'll deprecate Labour's general pusillanimity and failure to oppose workfare, and invoke the "spirit of 45" to call for a more radical push.

Personally, this attitude reminds me of those halfwits who ring 6-0-6 to demand that their team show more "passion" - as if "wanting it more" is sufficient to overcome strategic and technical deficiencies.

Instead, let's just remind ourselves of the constraints Labour politicians face:

- A large section of the public are hostile to socialist policies. They are ill-informed and prejudiced about welfare and immigration, and show no appetite for workers' democracy. This is partly because capitalism generates ideologies which help entrench itself, and partly for more atavistic reasons. Granted, the recent argument about welfare seems to have increased Labour's support - but this might be because of the party's ambivalence on the matter.

- We are still dominated by managerialist ideology - the idea that, despite evidence of its failure, organizations can be improved by better management control rather than workers' control.

- The desire to get a good job in their long post-ministerial lives encourages politicians to appear attractive to prospective capitalist employers, to seem no more than half-competent managers who won't threaten them.

- Capital has immense political power. This isn't just because it has the money to lobby for its particular interests, but also because it has a (semi?) credible threat to leave the country if it see policies it doesn't like, and because employment and activity depends upon its state of confidence.

The question is: how much room is there for the Labour leadership to display radical intentions within these constraints? My fear is: not much. There cannot be a successful left Thatcher. Labour's acceptance of so much of the status quo is not therefore due (merely) to supine personalities, but to a recognition of necessity.

What can we do about this? One possibility is to play a longer game, to try and shift the Overton window; this is what free market think tanks did in the 60s. If the new leftist movement proposed by Owen is anything more than an emoting circle-jerk, it's what it will do. The other possibility, suggested by Max, is to recognize that politics is not a place for grown ups.

Personally, I vacillate between these two positions.

April 9, 2013

Thatcher: successful failure

There's one point about Thatcher's premiership that I fear is being under-rated. It's that her success was partly inadvertent. I mean this in at least three different ways.

First, the recession of 1980-81 was not supposed to happen. The theory was that, by announcing credible targets for monetary growth, inflation expectations would fall and hence inflation would come down relatively painlessly. This, of course, did not happen. Monetary targets were overshot and we got a severe recession."Certainly it was a long way from the vision provided by the Conservatives in 1979" wrote David Smith (The Rise and Fall of Monetarism, p 103). And Tim Congdon wrote in 1982:

Monetarism was never intended as a form of corporal punishment on the British economy. No one wanted unemployment to reach three million and, as is clear from the forecasts made in 1979 and 1980, no one expected it to do so...All monetarists would have preferred the unemployment-inflation trade-off to be more favourable. (Reflections on Monetarism, p96)

But this corporal punishment had (for some!) a favourable side-effect. In clobbering labour's bargaining power, it helped increase profit margins and profit expectations and animal spirits, and thus laid the basis for stronger investment in the 1980s.

Yes, Thatcher promised to weaken the unions. But she envisaged doing so by reasserting the rule of law, not by creating mass unemployment.

Secondly, her relaxation of credit controls in the early 80s had a bigger economic impact than she intended. She envisaged these as a step towards economic freedom. But they were more than that. They permitted a consumer-driven society and economy. This was not her intention. As the Heresiarch rightly emphasises, her vision of Britain was of a property-owning democracy of savers with moral restraint. She got indebted spendthrifts. She wanted the British people to be like her father, but they turned out more like her son.

Thirdly, the closure of the coal mines did not turn out as planned. Thatcher claimed that the loss-making pits were "uneconomic." Her critics, such as Andrew Glyn, said this was mostly untrue because it was cheaper for the government to subsidise the pits than it would be to pay unemployment benefits. Thatcherites in turn responded by claiming that redundant miners would get work elsewhere. We now know that they were mostly wrong; employment in mining areas never fully (pdf) recovered (pdf) from the closures.The free market conception of a flexible labour force able to move easily from job to job was, in this respect, mistaken.

And yet the miners' strike is seen as a victory for Thatcher - as a triumph for capital or for the rule of law, depending on your taste (and, with anachronistic hindsight, a reduction in carbon emissions). The human cost of the pit closures, and the refutation of the (explicit) economic theory behind them are conveniently overlooked by Thatcher's supporters.

In these regards, Thatcher's success is another example of John Kay's obliquity - of achieving ends unintentionally.

And this raises a wider question. If the greatest political figure of the last 60 years was a success largely unintentionally, what does this tell us about the nature of politics?

April 8, 2013

Thatcher's good

Regular readers might have guessed that I am no admirer of Lady Thatcher.But on the principle that one shouldn't speak ill of the dead - and that no-one is wholly bad - here are some things I think she deserves some credit for:

1. Pragmatism. Although both left and right like to mythologize Thatcher as a slasher of public spending, this is not true. During her premiership, the share of spending in GDP fell less than it did in the early years of New Labour, and less than it's planned to fall in the next few years. And spending was higher under her than it was during the 1964-70 Labour government*. Nor was Thatcher a great reformer of the NHS. In both respects, she was driven more by practicality than ideological zeal.

2. A recognition that politicians can effect fundamental change. During the Thatcher years, the Overton window shifted. This wasn't just because her ideology triumphed. She helped it along partly by effecting hard-to-reverse changes such as privatization, and partly by changing the electorate; selling council houses created client voters. A Labour party which spinelessly kowtows to public opinion has something to learn here.

3. The Police and Criminal Evidence Act. In the 60s and 70s, the police were corrupt, racist thugs. PACE was an attempt to rein them in. Of course, Hillsborough and the miners' strike showed that this effort wasn't wholly successful. But Thatcher deserves credit for displaying a greater scepticism about the police than many later copper-worshipping Home Secretaries.

4. "You can't buck the market." Thatcher recognized that there are some things that governments cannot do - for example, control prices and wages by legislation. And Lawson's attempt to shadow the DMark in 1987-88, and the UK's entry into the ERM in 1990 proved her right.

5. Being lucky. Thatcher got lucky in her first term of office in at least two ways. Most obviously, the Falklands war boosted her popularity hugely. But also, the economy did not follow her script. She hoped that the mere announcement of M3 targets would reduce inflation painlessly, by reducing inflation expectations. This didn't happen. Instead, she inadvertently engineered a recession which destroyed workers' bargaining power, thus raising profit margins and (eventually) the motive to invest. In this sense, she reminds us of the importance of luck in politics (and in the latter case, structural economic relationships), relative to that of intentions.

6. Reducing snobbery. When Thatcher became Tory leader, she faced both gender and class snobbery; she was seen as a shrill lower middle-class housewife. Her success reduced class and gender prejudice amongst the rich. I suspect that my job prospects (as someone with an accent similar to her natural one) improved because of her. I fear, though, that this increased equality of opportunity was only temporary.

I don't say all this to sing her praises. I suspect her legacy is mostly a malign one and that she was more of a class warrior than a genuine libertarian. I do so merely to suggest that she was not wholly the devil the left pretends.

* Table 2.33 of the OBR's supplementary fiscal tables.

April 7, 2013

"Paying more in"

Over the last five years, I've paid almost £2000 in home insurance and got nothing back. This is unfair. It should change.

Now, anyone with an IQ higher than their hat size will spot a problem with this. Paying in more than you get back is not a fault of insurance but a feature. The point of insurance is to pool risk, so that the lucky - those who don't get burgled - pay in whilst the unlucky take out.

This shouldn't need saying. But it seems it does, because Liam Byrne writes:

we must do more to strengthen the old principle of contribution: there are lots of people right now who feel they pay an awful lot more in than they ever get back. That should change.

This is just confused. Even the best institutions for pooling economic risks - whatever your conception of them might be - will have some people pay an awful lot more in than they ever get back. This is simply because some people will be lucky and not suffer economic risks. This will be true however strong the principle of contribution is.

The only way you can avoid having some people not pay in more than they get out is to have no welfare state at all (and no private insurance for economic risks either). In this world, people would protect themselves against risk by saving and borrowing, in effect self-insuring.

So, what is Byrne doing here? One possibility is that he's just being stupid: he has form. The other possibility is that he's not. He's trying to pander to a prejudiced public who are ignorant of the facts of the welfare state by invoking a silly notion of a distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. I hope none of you were daft enough to think "divide and rule" was only a Tory strategy.

April 6, 2013

Benefits' biases

Alex Massie is, of course, correct to say that it is a mistake to draw any inferences from something as freakishly unusual as the Philpott case. Why, then, has the mistake been so common? I suspect there are two biases at work.

One is the confirmation bias. If you think the welfare state incentivizes bad behaviour such as laziness or fecklessness, you'll see Philpott as an extreme confirmation of your prior.

We should, here, note an asymmetry. Those who see Philpott as confirmation of the "bad incentive" hypothesis don't regard HBOS's bad lending as evidence that low top taxes have perverse incentives, or Stephen Seddon's murder of his parents as evidence that low inheritance taxes have bad incentives. This asymmetry cannot be explained by sound statistical reasoning, unless your prior is that the welfare state has stronger bad incentives than the tax system.

The second bias is a form of the halo effect.Hostility towards benefit claimants is founded upon a moral instinct - the norm of reciprocity. People fear that claimants are getting something for nothing, that "hard-working tax-payers" are being ripped off. The halo effect - the tendency to believe that all bad things are connected - lead people to think that such scrounging is also a macroeconomic problem. Which it isn't. This bias is exacerbated by our natural tendency to exaggerate harms done to us.

Herein, though, lies a problem. I fear this reciprocity norm is an atavistic instinct with an evolutionary basis which is no longer relevant to post-industrial society.

In hunter-gatherer societies struggling for subsistence the man who does no work and expects others to provide for him is a threat to the very existence of the tribe. It's natural, therefore, for a norm of reciprocity to emerge so that shirkers are stigmatized and shunned.

But we no longer live in that world. We have the opposite problem. There's not enough work to go round. In this world, the shirker does not threaten our existence. If anything, he's a help, as his not looking for work increases the chances of others getting it. And, remember, on average the unemployed are significantly unhappier than others.

My point here is a depressing one. The tendency to stigmatize benefit claimants, and so to regard Philpott as sufficiently representative of them to justify inferences (or dog-whistle "questions") is not the sort of error that can be corrected by evidence. It arises from biases and beliefs which are hardwired into us.

April 5, 2013

Rachel Riley & suboptimal choice

In the day job, I advise people to do a crossword before taking important financial decisions, because experiments suggest that a task which increases mental alertness can help people make more far-sighted choices.

I was going to recommend that people watch Countdown instead - but then I (quickly) realized that looking at Rachel Riley can stimulate more than the mind. And such stimuli can worsen financial decision-making. Testosterone leads to increased risk-taking, which can lead to financial crashes. More generally, experimental evidence (pdf) shows that higher levels of excitement can lead to price bubbles and hence crashes.

It is no coincidence that in the spring a young man's fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love and that "sell in May" is a great investment strategy. Better weather - which usually comes in the spring - tends to get us happier and more excited, and this raises share prices to levels which are often unsustainable. When shares rose, my first boss used to say "the market's got the horn." He was more right than he knew.

This is not the only example of how we can be influenced to make poor decisions. Here are two others:

- Researchers have found that creating an upmarket atmosphere in a restaurant - by playing classical music rather than Britney Spears - causes people to spend more. This corroborates Robert Frank's fear, that conspicuous consumption, in also creating a sense of affluence, can cause other people to spend more than they otherwise would.

- Women can be primed to act girly. For example, when they go to a mixed-sex school they are more likely to make low-paying "feminine" career choices and to shy away from competition than if they attend single-sex establishments.

There's a common theme here. Our choices can be influenced by contexts and stimuli in ways of which we are not fully aware. As a result, our preferences might not best serve our interests. And if this is true for investment, spending and career choices, might it not also be true in other realms, such as politics?

April 4, 2013

Entrenching inequality

Does inequality feed on itself? Some recent experiments by Jeffrey Butler suggests the answer is: yes.

He got subjects to play an urn-guessing game. They were presented with two urns, one with with mostly red balls and another with mostly white, and were asked to guess which of two urns the experimenter was using, based upon seeing one ball drawn. Subjects were split randomly into two groups, one being better paid than the other.

Both the low-paid and high-paid groups got roughly the same amount of guesses right.However, when they were asked: are you a better or worse than average guesser? things changed. Whereas 85% of the high-paid group said they were better than average, only 60% of the low-paid group did. Butler says:

Inequality undermines the confidence of the disadvantaged and boosts the con�dence of the advantaged.

This confidence is not just idle talk. In other experiments, Butler found that more confident subjects were more likely to choose to enter winner-take-all tournaments, thus increasing their chances of big payoffs later.

This implies that initially arbitrary inequality can become persistent, because it reduces the desire of the worst-off to compete.(This is, of course, only one of several routes in which this can happen).

It's easy to see that this might have real-world applications.It's consistent with Afro-Caribbean boys doing poorly at school; with working class kids being loath to apply to Oxbridge; and with women not applying for top jobs. It's also consistent with some of the unemployed not wanting to work: why apply for jobs if you'll only be knocked back?

This implies that a popular explanation for inequality might be no explanation at all. It's sometimes claimed that the successful are successful because they worked hard and the unemployed are unemployed because they are lazy. But this research suggests the causality might be reversed. Maybe successful people work hard because prior good luck has led them to think that work pays, whilst others are lazy because bad luck has reduced their confidence. In other words, it could be that the preferences which rightists believe to be the cause of inequality are in fact the effect of it.

We know from research in personal finance that preferences for risk are partly endogenous; people who have experienced recession (pdf) or the death of a child are more risk averse than others. Wouldn't it be remarkable if risk appetite was the only endogenous preference? If ambition and appetite for work are also endogenous, then a moralistic defence of inequality becomes less tenable.

April 3, 2013

Scrounging: how big an issue?

George Osborne wants benefit claimants to "do the right thing" and move into work. This, though, might not make very much difference to the economy.

The first question is: how many claimants don't want to work? As a rough pass, let's assume it is the number of unemployed who report very high subjective well-being; 9 or 10 on the ONS's 0-10 scale. 16.3% of the unemployed do so, which equates to 411,000 people.

Now, this could be an over-estimate, as it includes people who naturally have a sunny disposition, and folk who are happy because they expect to get work soon. But let's run with this.

Let's assume that all these could find full-time work at the national minimum wage. Let's assume too that employers are just waiting to hire so many (humour me). These folk would then earn £11885 a year; £6.19 for 40 hours a week and 48 weeks a year. £11885 multiplied by 411,000 gives us £4885m. Of course, employers would make a profit by employing these people. Let's assume that the ratio of profits to wages for these folk is the same as it is in the whole economy, at 37% (table D of this pdf); I'm ignoring diminishing returns here. This gives us £1807m of profits.

Add the two together and we have £6.69bn. This is 0.43% of annual GDP.

Of course, this is worth having. But it's not a massive sum. It's less than one quarter's of ordinary GDP growth.

Let's put this is context. If non-oil GDP had grown by just 1.5% a year since 2007Q4, the economy would be 9.6% bigger than it actually is. Scroungers and layabouts, then, cost the economy about one-twentieth as much as the recession has.

Of course, this is just the back of a beermat estimate and not a hard fact. You could get it higher if you assume there are more "scroungers" or if you assume that they could get higher wage work. Personally, I find these improbable - though I'll concede that Mick Philpott's intelligence and honesty would have equipped him well for a successful banking career.

You could increase my estimate in some other ways. You could claim that there would be powerful multiplier effects from "scroungers" moving into work. But it would be odd for defenders of fiscal austerity to suddenly discover big multipliers.

Or you could argue that low-wage workers are complements to higher-wage ones, so that the latter's earnings would rise as the former increase in numbers. But it would also be odd for supporters of immigration controls to suddenly adopt one of the economic arguments for open borders.

However, you cut it, then, the cost to the economy of layabouts - in terms of GDP foregone - is small.

There's a message here for left and right.

For the right, it's just plain wrong to think that "scrounging" is a serious macroeconomic issue. You might think it a moral failing. But don't confuse macroeconomics and morals.

For the left, you don't need to pretend that all benefit claimants are saintly victims in order to deny that scrounging is a serious economic issue. Even if we concede that there are tens of thousands of such scroungers, we can still maintain that getting them into work is not a top priority. A much bigger priority should be creating jobs for those who do want to work.

April 2, 2013

Money hopes

Today's economic news has been mostly bad, with the Bank reporting (pdf) falls in mortgage approvals and non-financial companies' borrowing, and purchasing managers saying that manufacturing output fell last month. But there's one sign of hope. It's that non-financial companies' UK sterling bank deposits have risen quite sharply. They're up by 7.8% year-on-year, the biggest annual rise since December 2007.

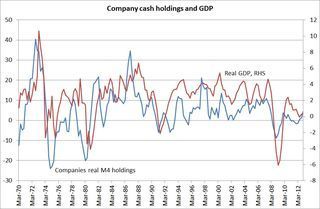

My chart shows why this matters. There's a good correlation between companies' M4 growth (inflation-adjusted) and GDP growth. The best lag is two quarters, with money growth leading output growth.Eyeball econometrics - an under-rated discipline - suggests there's little sign of this relationship having broken down recently.

This relationship suggests that, at worst, the risk of serious recession is fading and, at best, that we're heading for recovery.

The obvious reason for such a link is simply that companies build up cash with the intention of spending it on capital or labour. If they were simply pessimistic about their prospects, they would not hold cash but rather hand it back to their owners.

There are, though, two caveats here. One is that the relationship between corporate M4 and GDP is stronger on the downside than upside; money predicts recessions better than booms. The other is that companies might be hoarding cash for precautionary reasons. The fear that credit lines might be withdrawn in future is causing them to have big bank balances as protection against this.

Two things, however, make me suspect these are no more than caveats:

1. Today's BCC survey shows a small rise in investment intentions, corroborating the message of M4.

2. There's recently been a decline in companies' financial surplus and a rise in PE ratios. Both are consistent with a pick-up in growth expectations and hence in the motive to invest.

The good news, then, is that the economy might be about to recover. The great news is that this might - only might - mean that the economy's long-term problem of a dearth of monetizable investment opportunities could be receding. The bad news is that, if the recovery does come, the Tories will claim this as vindication of its austerity policies.

April 1, 2013

Don't blame PPE

Many tweeters have been laying into Oxford PPEists. Faisal Islam says they are "to blame for most UK problems", and the Renegade Economist says "PPE at Oxford University has had a disastrous effect."

Being a PPEist myself, I'm flattered to think I have such influence, but I don't think this is right, for three reasons.

1. It's not obvious what pernicious beliefs are instilled by PPE. The syllabus is so diverse that it can't convey a united body of knowledge and ideology; it's possible for two PPEists not to study a single common course after their first year. What is it that Nick Cohen, Seamus Milne, Toby Young, Ann Widdecombe, David Cameron and I have in common*? And Oxford certainly doesn't endorse right-wing ideology. Corpuscules and Balliolites in the mid-80s tutors and lecturers' included Andrew Glyn, Steven Lukes, Wendy Carlin and David Soskice, none of whom were famed for supporting neoliberalism or austerity - a tradition followed by Simon Wren Lewis**.

2. A PPE degree is like fame or wealth - it doesn't create character, so much as reveal it. Granted, PPEists include a lot of rum characters. But this could be a simple selection effect. The most able and ambitious young people who are interested in politics are disproportionately likely to do PPE at Oxford, and they are disproportionately likely to go onto careers in politics. There will therefore be a huge proportion of Oxford PPEists in politics. But this might not have anything to do with PPE causing people to become MPs and ministers.

3. The belief that PPE is responsible for neoliberal politics attributes too much power to politicians' agency and not enough to power structures. The fact is that we live in a post-democratic age (to use a phrase of another former PPE tutor) in which politics is shaped by the power and ideology of capital. These constraints influence politicians' behaviour much more than does their educational background.

* Self-opinionated arrogance, you might say. Whether this is because of selection (such qualities equipped us well for the admission interviews) or causality is, however, unclear.

** One could argue that PPE tutors have or had a leftist bias, but this is not the allegation being levelled on Twitter now.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers