Chris Dillow's Blog, page 158

February 4, 2013

Productivity puzzles & NGDP targets

Duncan Weldon says:

Many of the supposed supply constraints the UK economy currently faces are actually related to problems on the demand side of the economy. Boosting demand now would boost productivity.

I'm not so sure. Some agree (pdf) with Duncan, others are less(pdf) certain. As Simon says, the causes of the productivity stagnation are not well known.

But Duncan's hypothesis can be tested. Why not boost demand and find out?

Herein, I fear, lies a problem with the inflation target.Taken literally, it penalizes avoidable inflation, but not avoidable unemployment.It thus rules out taking the risk of raising inflation, but permits the risk of tolerating what, if Duncan's right, would prove to be unnecessarily weak demand.

This bias is absurd.People hate (pdf) unemployment as well as inflation.So, surely, unemployment should have a weight in the policy target - as it has in the US.

Now, this absurdity was not supposed to arise. If you think the economy is buffetted only by demand shocks, there's no trade-off between targeting inflation and unemployment: when demand's weak, inflation is expected to fall and so policies that boost demand and cut unemployment are compatible with the inflation target.

However, when the economy is hit by supply shocks or by shocks that we can't easily identify as demand or supply ones then the trade-off does emerge.

This suggests a case for targeting nominal GDP. Doing so recognizes what should be obvious - that unemployment matters as well as inflation.

One counter to this is that such a target doesn't recognize the difference between real and nominal growth. It is indifferent between 5% inflation and zero real growth and 5% real growth and zero inflation.

I'm not convinced by this. If nominal GDP is growing by (say) 5% a year, we can say that monetary policy is doing its job. If the growth-inflation split is undesireable, then the answer lies in supply-side policies to improve that split, not necessarily in tighter monetary policy*.

Instead, my scepticism about NGDP targeting is that I'm not sure it would be much different from what we've had; if you've got no gun, it doesn't much matter what your target is.

And, remember, monetary policy isn't the only weapon we have. You can, y'know, boost demand by fiscal policy.

* The counter-objection to this is that if high inflation expectations become embedded then it's costly to get them down, but this is another story.

February 3, 2013

Living wage trade-offs

How should we think about trade-offs in economic policy? Some tweets by Jon Stone have raised this question.

To see the issue, take the Resolution Foundation's estimate (pdf) of the effect of fully implementing a living wage. It reckons such a policy would raise the gross earnings of around five million workers by a total of £6.5bn, though some £2.9bn of this would be clawed back by the government in the form of higher taxes and lower tax credits and benefits.However, the higher wages would cost 160,000 jobs.

For the sake of argument, let's assume these numbers are roughly right. Is the cost of 160,000 jobs a good trade for higher net incomes for millions?

In terms of workers' raw income, the answer's yes: the £3.6bn rise for those who keep their jobs outweighs the income lost by those losing their jobs.

Measured by well-being, however, it's a closer call. Wellbeing increases only weakly with income, but falls sharply with job loss. This means that we need lots of winners from a living wage to offset the unemployment of a few.

We can roughly quantify this. A paper by Nattavudh Powdthavee suggests that, in terms of wellbeing, we need a 30% rise in income to offset being unemployed. This means that if the average winner from a living wage gains 3%, we need at least 10 winners for every unemployed*.

You might think this condition is fulfilled. It is, if we consider only the wellbeing of those earning less than the living wage. But their higher wages come at the expense of profits. How much you're troubled by this depends on how you regard those employers. Are they exploitative tax-fiddling mega corporations, or are they small businesses struggling to get by?

And then there's the standard question about utilitarianism: is it legitimate to impose (largeish) costs upon a minority so that the majority enjoy other benefits?

These concerns explain why many supporters of a living wage don't think it is something that should be mandated by legislation, but rather campaigned for on a workplace-by-workplace basis.This, though, runs into the problem that unions - the intelligent, non-statist way of improving workers' living standards - just don't have the bargaining power to do this.

There is, however, a way to improve workers' bargaining power - to have a (high) basic income which gives workers a decent outside option and thus greater ability to reject exploitative working conditions.

Which raises the question: why is the campaign for a living wage so much more popular than that for a basic income? I suspect the answer has less to do with technocratic or high-brow ethical considerations than an appeal to reciprocity: the living wage demands that hard workers get a "fair" deal. But I wonder whether such appeals - powerful as they are - are a sufficient basis for policy.

* 3% might seem small. But remember that many people earn only a few pennies less than the living wage (which is one reason why it would destroy so few jobs), and others are second earners in quite well-off families. I say "at least" because this calcuation ignores the income loss of the unemployed themselves.

Another thing: You can't justify a living wage by its net gain to the Treasury - that's just deficit fetishism.

February 2, 2013

Diversifying mental states

My boiler has been faulty this week, which has set me thinking that modern portfolio theory can be applied not just to financial assets, but to mental states.

What I mean is that having to work distracted from the hassle of thinking about the boiler: will the gasman come? Will he fix it? How much will it cost? The upshot was that I was less agitated than I'd otherwise have been.

What happened here was an application of MPT - an idea which with a little thought (that is, more thought than banks ever gave it) - is still one of the most powerful in finance.

Think of everything you have - car, job, friends, family, central heating, whatever - as assets with payoffs which are sometimes positive, sometimes negative (your car breaks down, you row with your wife and so on). If these payoffs are positively correlated, then your happiness will vary hugely: sometimes everything will go well, sometimes eveything badly. If, however, they are negatively correlated then your mental state will be more stable. And this is what happened to me. My job has a (lowish!) payoff in terms of my well-being. But that payoff is uncorrelated with other negative payoffs in my life, with the result that it stops me getting too down. In effect, my mental states are diversified.

I don't think I'm eccentric here. When men half-joke that they go to work to get some peace from their families, they're expressing a similar idea: the psychological payoff to work is uncorrelated with the psychological payoff to family life, causing one to diversify the other.

This analogy helps illuminate several facts about happiness:

1. Why are the unemployed unhappy, even controlling for income? One reason is that they lose the diversifying power of work for well-being, with the result that otherwise tolerable niggles - noisy neighbours, a rocky marriage or general down-in-the-dumpsness - hurt more. Another reason is that the loss of a job is associated with other losses - not just of income but of social contacts too. It is not single losses which are disastrous, but correlated ones.

2. Why are people who watch lots of TV (often) unhappier than others? It's because watching TV isn't sufficiently engaging an acitivity to distract us from the stresses of the day. It doesn't generate the "flow" that, say, playing guitar does.

3.Why are religious people often happier than others? A big reason is that religion is a form of insurance, an asset that pays off well in bad states of the world, such as bereavement or unemployment, thus preventing big falls in well-being. Those who reply that religious belief is irrational are like those who claim that a financial asset is over-priced; the statement is only relevant if holders of the asset come to believe it.

There is, however, another analogy between MPT and well-being. Diversification doesn't just reduce downside risk, but upside risk too. The serial shagger or bachelor with a rich internal life might never know a broken heart, but he'll never know the glory of true love either.

February 1, 2013

The "nation's finances"

Francis Maude writes:

We have made good progress at putting the nation’s finances on a more stable footing - cutting the deficit we inherited by a quarter.

Leave aside the fact that cutting the deficit by a quarter is no great achievement. I want to complain about that phrase, "the nation's finances". Mr Maude is not referring to the nation's finances, but the government's. And the government and the nation are not the same thing.

However, this trope is not confined to Mr Maude. On yesterday's PM programme (21 min in), Tory councillor Simon Hoare spoke of "the mess the Labour party left in the national finances." Journalists repeat the phrase. The Mail has written of a "black hole in the nation's finances." And the BBC has described the OBR as "a body set up by Mr Osborne to provide independent analysis of the nation's finances."

My objection to this phrase isn't mere pedantry. It can disguise a logical error, demonstrated by Oxfam:

Illegal tax evasion is depriving the UK economy of £5.2 billion a year.

No. If a man dodges £100 of tax, he's £100 better off and the Exchequer is £100 worse off. Net, the UK economy is not deprived at all - or at least, if you think it is, you need to say a lot more about why.

This conflation of the government's finances with the nation's finances has two unpleasant effects.

One is that it stops us seeing the key fact - that the reason why the public finances are in deficit is that other parts of the economy, most notably the corporate sector, are in surplus. If you define "nation's finances" as the financial balances of everyone in the nation, you could easily argue that our problem is that a large part of the nation's finances are too healthy - companies have got too many assets in the bank and not enough in the workplace in the form of capital investment.

Secondly, rhetoric about the "nation's finances" can lead to a fetishism of the deficit, whereby policies are judged only by their impact upon government borrowing. Hopi Sen parodied this thus (at least, I hope it was a parody):

Because the research [pdf] suggests that the Treasury would save £2.2 billion a year under such a scheme, given a reasonably creative press officer and a friendly journalist, the Living Wage could even become a plan to balance the books on the backs of 160,000 extra unemployed!

300 years ago, people used to judge the health an economy by its trade balance. Today, they seem to do so by its government balance. So much for progress.

January 31, 2013

Wages, fairness & productivity

Do higher wages motivate workers to work harder? A recent experiment conducted on Swiss newspaper distributors suggests the answer's yes, but only partially so:

Workers who perceive being underpaid at the base wage increase their performance if the hourly wage increases, while those who feel adequately paid or overpaid at the base wage do not change their performance.

This suggests that people are motivated not so much by the cold cash nexus as by feelings of reciprocal fairness*.

You might interpret this as an argument for a living wage (pdf): if it causes poorly-paid workers to raise their productivity, it might pay for itself. I'm not sure, for two reasons.

First, I'm not sure how great is the overlap between actual pay and the feeling of being unfairly paid. Anyone who's been in an investment bank at bonus time will know that there's a difference between the two. It could be that the just world illusion mitigates self-serving biases, causing some low-paid workers not to feel unjustly treated.At the last general election, 31% of people in the DE social class voted Tory.

Secondly, even if a living wage does raise productivity, it could still destroy jobs. If it causes a chambermaid to clean an extra room per shift, the living wage might merely allow hotels to employ fewer chambermaids.

Efficiency wage models, remember, are models of unemployment.

* Of course, higher wages might be necessary to attract workers in the first place, but this is not the same as motivated them to work harder once they're in the job.

January 30, 2013

Mario Balotelli & primitive accumulation

Mario Balotelli's transfer to AC Milan highlights the Marxian critique of capitalism.

How can Man City get £19m for a player who is so obviously flawed? The answer's simple. It's because their great wealth means they did not need to sell him, and so could drive a hard bargain. The party in the strongest bargaining position gets most of the surplus from any trade.

As the old saying goes, "money begets money." Wealth - or what amounts to the same thing, cheap and easy access to capital - can be used to get the better end of deals. For example:

- Being cash-rich gives you the chance to profit from fire sales and desperate fund-raisings, as when Warren Buffett lent to Goldmans in 2008.

- Companies that are cash-rich or have a low cost of capital can use this to engage in roll-ups and multiple arbitrage and so profit from taking over businesses even if they do not manage them much better.

- Banks can "hoover up pennies" - make low-profit quasi-arbitrage trades - if their cost of capital is low enough. This is why they are so opposed to Volcker rules and the ending of "too big to fail" subsidies; they raise capital costs and thus render a lot of their activities unprofitable.

- If you have access to easy money, you can profit by lending this at high rates to desperate borrowers, or by selling low-value insurance (pet insurance, extended warranties etc) to the cash-poor.

All this should be trivial. Marxists, however, add to this list the capital-labour relationship. In most cases - top footballers being an exception - physical capital is scarce and labour abundant. And this means capital can extract most of the surplus generated from the trade between capital and labour. Sure, workers are better off working than not. But their poor bargaining position means they are not much so. And this begets exploitation. Exploitation, says John Roemer, is "the distributional consequence of an unjust inequality in the distribution of productive assets and resources."

That word "unjust" is doing some work. Buffett's trade with Goldmans was good for him and bad for them, but we wouldn't really call it exploitative because the inequality that begat it was not unjust.

So, is the inequality between worker and capitalist unjust? You can certainly tell just-so stories in which it isn't. But Marxists take a historical perspective. Marx devoted a large part of Capital vol I to describing "primitive accumulation", the process whereby capital came into the world as a result of theft, slavery and conquest: "capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt." This is, of course, no mere history: how did Russian oligarchs get rich?

An overlooked difference between Marxists and their opponents is that Marxists think this matters.

January 29, 2013

"History & brand"

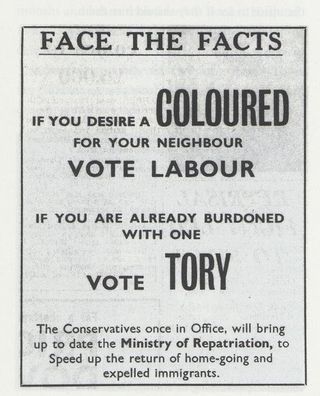

In discussing the Tories lack of support (pdf) among ethnic minorities, Rachel Sylvester in the Times (£) quotes a Tory strategist: "This is nothing to do with class or ideology. It's to do with history and brand."

This poses the question: could it be that voting behaviour, like so much else, is shaped by history?

What makes me suspect so is that successful brands are the product not of marketing campaigns but of history. Products such as Cadbury's chocolate, Bird's custard and Colman's mustard took off in the 19th century because they were initially better than rival products, and this built a trust that lasted.

And herein lies the Tories' problem. Ethnic minorities remember that, in the 60s, Tories hated them: "If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour." And just as people support Man United - probably Britain's biggest brand - because Charlton, Best and Law played for them, so they shun the Tories because of (folk) memories of the 60s.

In this sense, perhaps the Tories' anti-immigration policy backfires. Whilst it might appeal to the interests of (some? many?) ethnic minorites who compete in the labour market against new immigrants, it also reminds us of when the Tories really were the nasty party.

This poses the question: can the Tories rebrand themselves? I doubt it.

Branding needs an empirical basis; marketers can't fool the public for long. As Jonathan Salem Baskin says:

Branding is based on an outdated and invalid desire to manipulate and control consumers' unconscious. It looks good and feels good to the people who produce it, but it has little to no effect on consumer behaviour...It is the conceit that marketers can convince them of things that aren't substantiated by fact or the reality of experience. (Branding only Works on Cattle p14, 17)

Because of this, many efforts at rebranding have failed: think of the Post Office calling itself Consgnia or HMV's efforts to sell electronic tat. Where rebranding has worked, it's been through luck (eg Burberry's appeal to urban youth in the 90s), or through good new products (such as Apple's shift from computers to iPods and phones, or Sony's entry into games consoles markets) or because the company has a longstanding appeal that only needs brushing up (eg Marks & Spencers passim). It's not clear that the Tories have any of these advantages.

Of course, the Tories' actual policy platform isn't hostile to ethnic minorites any more - it's difficult to see a policy reason why Indians should split 61-24 in favour of Labour over the Tories - but this is not sufficient. If a car is going downhill, it won't change direction if you only put it into a neutral gear.

Perhaps, therefore, the Tories are victims of path-dependency. Maybe marketing men cannot fight against history.

January 28, 2013

Socialism, institutions & human nature

Owen Jones says: "As a socialist, I am compelled to have an optimistic view of humanity, to believe we are not all motivated by greed, selfishness or hate." I have problems with this.

First, the way Owen puts this, it looks like wishful thinking; his view of an objective fact (human nature) is motivated by political beliefs. This is surely irrational.Human nature is what it is, whether you're a socialist or not.

My bigger gripe, though, is that I'm not sure such idealism is necessary for socialism at all.

Put it this way. Owen is surely right to say that the Holocaust - and I'd add much else in history - shows the "almost infinite malleability of humanity": we are capable of great evil and great good.

The question, therefore, for socialists and everyone else is: through what mechanisms and institutions is behaviour shaped? Could socialistic institutions generate more good behaviour and less bad than capitalistic ones? There are (at least) three reasons to think so:

1. We know from the orthodox economics of crime and from Ben Friedman's historical research that people who are fearful, poor and insecure tend to behave worse than those who are not. This suggests that egalitarian institutions should reduce crime and violence, and perhaps intolerance generally.

2. Hierarchical companies have (built-in?) adverse selection mechanisms; their leaders are selected to be irrational, narcissists or psychopaths. And market forces might not select against companies run by such people.

Of course, the problem here is not capitalism but any hierarchy: Stalin's USSR and Fred Goodwin's RBS both demonstrate my point. It is for this reason that socialism must be non-hierarchical.

3.There's reasonable evidence that worker-managed firms are at least (pdf) as efficient as similar (pdf) capitalistic ones, perhaps because peer pressure helps boost productivity. This suggests that egalitarian institutions can restrain our selfish impulses to be lazy whilst others do the work.

In these respects, socialism - which is not the same as statism, mad libertarians please note - has the edge.

The big open question, however, concerns the role of markets. You could interpret these as a fantastic mechanism for converting selfish impulses into social benefits, as Smith did when he said "it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest."

On the other hand, though, we know that the cash incentives used by markets can crowd out intrinsic motives and creativity so that selfishness is economically inefficient.

My point here is not to cheer for socialism, or to make sweeping generalizations. Instead, it is merely to suggest that socialism - for me anyway! - is not about hippy-dippy all-you-need-is love idealism, nor about emoting about "unfair" capitalism. Instead, it is question about the interplay of institutions and behaviour.

January 26, 2013

Cripps' message

Boris Johnson's reference to the "hair shirt, Stafford Cripps agenda" raises more mischief than perhaps he realises.

This is because Cripps' austerity - even more than the 1980s tightening is an example of expansionary fiscal contraction.

Cripps' fiscal policy was certainly tight. His 1948 Budget, for example, called for "an exceptionally large Budget surplus*." The primary budget balance - which was in deficit of 12.4% of GDP in 1945 - was in a surplus of 3.9% in 1947 when he became Chancellor, and he increased this to over 9% of GDP by 1950.This is a bigger tightening than Osborne is planning; the OBR envisages the primary deficit falling from 5% of GDP in 2011-12 to 1.8% in 2015-16.

However, this tightening - which was achieved mostly by a rise in the share of taxes in GDP - was accompanied by an economic boom. Between 1947 and 1951, GDP grew by 3.5% a year, investment by 5.6%, exports by 11.1% and industrial production by 5.8% a year, whilst the unemployment rate stayed below 1.5%.

Such growth was, of course, facilitated by the massive backlog of investment opportunities which was opened up by the war - including the need to rebuild houses.

And herein lies Johnson's mischief-making. This episode draws our attention to two points.

First, the failure of Osborne's fiscal policy shows not merely that he is a lousy economist, but a poor historian too. A good historian would have asked: under what conditions has fiscal austerity been accompanied by good economic growth in the past? Whether he looked at the early 80s or the post-war period, he would have seen the same thing - that the circumstances in which austerity works are very different from those that exist now.

Secondly, strong growth during the post-war reconstruction period has caused commentators for years to exaggerate the "natural" vigour of capitalism. Between 1948 and 1973, real GDP per head grew by 2.5% a year. But this was exceptional. Since then, it has grown just 1.8% a year, and in the 118 years before 1948 it grew just 1% a year.

In this sense, those who talk about modest growth being the "new normal" are lacking historical perspective. A sluggish economy is in fact the old normal.

* The motive for this was to reduce inflation, rather than to repay debt as an aim in itself.

January 25, 2013

Remember animal spirits?

There's one reaction to the UK's lack of meaningful economic recovery that is surprisingly absent.

To see it, remember that a big reason for our slow growth is a lack of capital spending; the volume of business investment, though up from its 2009 low-point, is still 11.6% below its 2007Q4 peak.

But why is capital spending so weak? There are lots of possibilities: the slowdown in technical progress has created a dearth of investment opportunities; fears that banks will restrict future credit lines are causing firms to hoard cash; falling real wages are encouraging labour-capital substitution; and spare capacity and weak demand mean there's little need to expand.

I don't want to reject any of these. But there's another possibility, raised in a new paper by Charles Lee and Salman Arif - that investment and the recovery are held back by depressed animal spirits.

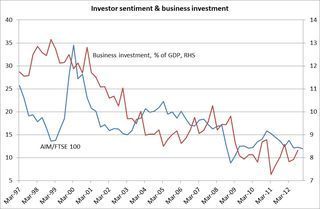

They point out that business investment is well correlated with investors' sentiment towards shares. My chart shows that a similar thing is true in the UK. We can measure sentiment by the ratio of Aim stocks to the FTSE 100; Aim shares tend to be smaller, less well-known and more speculative than bigger shares, and so high prices for them are a sign of high spirits. You can see that this ratio has tended to predict business investment, with a lag - the lag being because it takes time for investment decisions to translate into actual spending.

Of course, a correlation between investor sentiment and capital spending might exist simply because rational expectations of the future determine both. If so, then current weak sentiment and weak investment are a sign of weak future growth.

But Lee and Arif's work suggests this might not be so. They estimate that, in most advanced countries, high investment leads to weaker GDP growth and falling profits. That's exactly the opposite of what you'd expect if sentiment and investment were rationally determined.

This leaves us with another possibility - that it is irrational animal spirits that drive sentiment and capital spending. And herein lies the point that is not widely made. It's that the economy is being depressed in part by company bosses being irrationally pessimistic. We're paying the price for stupidity in boardrooms.

Such a reaction should appeal to both Keynesians - who coined the phrase "animal spirits"? - and to government supporters wanting to deflect blame from Osborne.

And yet it is rarely heard.I suspect one reason for this lies in the power of managerialist ideology. Whilst the ruling class are quick to attribute irrationality to ordinary people, they are blind to the possibility that irrationality can also be found at the top of hierarchies.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers