Chris Dillow's Blog, page 142

September 11, 2013

Social democrats' structural failure

Janan Ganesh says, rightly I suspect:

Lehman’s collapse did not whet people’s appetite for the left’s creed. Any loss of faith in the market was not matched by a revival of faith in the state.

There are plenty of bad reasons why this should be so - among them a fear of government debt and the belief that Labour got banking regulation wrong (hint: hindsight bias). But there's one justification I'd like to highlight. It's that the collapse of banks brought into question governmental structures as well as private sector ones.

By this I mean two things.

First, banks' losses show that large complex organizations cannot be run well by centralized hierarchies; to what extent this is because of principal-agent failures and to what extent because of bounded information and rationality needn't worry us in my context. But this is true of governments as well as mega corporations. The claim "CEOs can't know enough to manage banks well" is very similar to the claim "government ministers can't know enough to manage public spending well."

In this sense, banking failures should have reduced faith in top-down management - and this naturally undermines statist social democracy.

Secondly, the banking crisis was a failure of networks. There's one fact about the crisis thast isn't emphasized enough. It's that banks' losses were rather small in a macroeconomic context. The ten US banks that lost the most had combined losses of $127bn. But this is only a fraction of the $6.8 trillion investors lost when US shares fell during the bursting of the tech bubble. Why, then, should massive losses have led to only the mildest recession, when much smaller losses caused depression? One reason, arising from my first point, is that banks' were highly leveraged whereas most equity investors' weren't. Another reason - described (pdf) by Haldane and May - is that banks were so densely interconnected that losses in some led to widespread liquidity hoarding, so that the impact of individual losses were magnified in a way that didn't happen in the tech burst.

This represents another structural failure. Tight, interconnected networks are vulnerable to a common failure in a way that looser ones - what Haldane calls "dissociative structures" - are not.

Again, this represents a challenge to statist social democracy. Policy is traditionally formed and delivered by tight, closed networks - a handful of close colleagues (often from similar backgrounds) make policy, and a few agencies deliver it. The danger of groupthink and system-wide failure is thus high.

In this sense, the left has missed an opportunity - but then, the history of the left is one of missed opportunities. It could have used the crisis to develop ideas of non-hierarchical, decentralized, open networks - and in fairness, the Occupy movement was edging towards this. But statist social democrats missed this chance. They still seem to think that the problem with politics and business is simply that the wrong people are in charge, when in fact the problem is (also) that the wrong systems are in place.

September 10, 2013

The management question

What do bosses do? This old question has gained new force from two recent stories: that BBC bosses siphoned off licence-payers money for themselves, and the FT's report that many managers fail a most basic question about probabilities. If we put these two items together, we have an obvious inference - that managers are not skilled decision-makers who add value to their organizations, but mere parasites.

But can we generalize from just two stories? Maybe.

Certainly, big payoffs are common for bosses. As Rick says, managers' entitlement culture isn't confined to the BBC. Bob Diamond, Rebekah Brooks, Stephen Hester, Nick Buckles and Tony Hayward, to name a few, all left their companies with payments greater than a typical worker will get in all his working lifetime - and not always after meritorious performance. Don't reply that these case are unlike the BBC's in that they were contractual entitlements. Bosses' power manifests itself in their ability to get generous contracts; the law isn't a constraint on power, but also a means through which power is exercised.

There's also evidence that managerial ability is limited. Nick Bloom and colleagues have shown that there's a long tail of second-rate management in the UK. Staffan Canback has described how diseconomies of scale set in quite quickly, implying that managers often cannot overcome bureaucratic limits to efficiency. Alex Coad has shown that there's a large random element to firm growth, implying that bosses contribute less to corporate success than they claim. Paul Ormerod and Bridget Rosewall have shown that corporate collapses are unforeseeable (pdf), implying that bosses perhaps can't prevent even huge disasters. Jeffrey Nielsen has argued that corporate hierarchies have a demotivating effect on workers. And there is no evidence that the rise of managerialism since the 1980s has contributed to better productivity growth or macroeconomic performance.

So, maybe the new evidence corroborates Stephen Marglin's old contention (pdf), that bosses' role is one of extracting incomes for themselves rather than increasing the size of the economic pie for everyone.

However, the point of this post is not to claim this definitively, but merely to point out that we have a reasonable question here which is not being asked by the mainstream media. The BBC story is framed in conventional journalistic terms - "who knew what and when" - as a story only about the BBC. The question of whether it tells us anything about management more generally is not asked. The ideology of leadership is so dominant that the media and political class cannot even see that it is questionable.

Herein we see just how powerful the boss class has become. It's not that bosses can defeat challenges to their power, but that such challenges don't even arise. As Steven Lukes wrote:

Is it not the supreme and most insidious use of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural and unchangeable? (Power, A Radical View, p28)

September 9, 2013

Post-seriousness

In the last few days I've blogged on subjects ranging from Syria and macroeconomics to football, tattoos and Miley Cyrus, prompting the question: am I serious or not?

The fact is, I can't tell the difference. Westminster politics is supposed to be serious. But is it? Nick Cohen's description of Nick Clegg - "a beta male, a mediocre conformist" - or David Aaronovitch's of Ed Miliband ("he is not a presence at all, he is an absence") could apply to most frontbenchers. They rely for what little credibility they have upon the gravitas of office: would anyone really take seriously George Osborne's thoughts (by which I mean stream of cliches) on the economy if he weren't Chancellor? Would he even have any thoughts?

Satire used to thrive by undermining the pompousness and high-mindedness of politics. But this is no longer possible. Nobody notices when you puncture a deflated balloon. Satire - be it The Thick of It or the Daily Mash - seems indistinguishable from good reportage.

Which is in turn easily distinguished from actual reportage. A lot of political reporting consists either of trivial Kremlinology - a description of a soap opera in which most "characters" are interchangeable one-dimensional cyphers - or of an unquestioning imposition of an ideology which fetishizes "strong leadership."

Of course, millions of people are suffering because of political decisions. But whilst their troubles are serious, the politics that caused them are not.

If allegedly serious subjects aren't serious, then the opposite is also true - "light" subjects contain important messages.

Back in the early 90s, when his bellendery was of only measurable proportions, Toby Young helped found the Modern Review, with the tagline "low culture for high-brows." It was an important insight. So-called "low culture" such as Miley and TV programmes can raise interesting economic issues at least as often as does Westminster politics; economics, remember, is not just (or even mainly) macroeconomics.

There's another reason for taking "low culture" seriously.It's that the culture, ideology and cognitive biases that help sustain inequality don't just manifest themselves in formal party political statements, but in our everyday lives; this is the truth captured by the often misused phrase, "the personal is the political." Ideology is manifested in tattoos and football as much as in "serious" matters.

It's an easy trick for writers to contend that we live in a post-something age - post-modern, post-ideological, post-industrial, post-truth, whatever. Perhaps we live in a post-serious age.

September 8, 2013

Bringing economics into disrepute

Matthew Parris in the Times (£) corroborates one of my concerns - that forecasting brings economics into disrepute. He notes that the economy seems to be recovering, contrary to the forecasts of David Blanchflower, Jonathan Portes and Martin Wolf. And he asks: is there any point to economists?:

We can all make vague, undated long-term predictions., but the expertise we look for in professional analysts is to name the dates. Where's the evidence that economists are any good at this?...In their timings they're hardly better than astrologers...Perhaps if we stopped calling them economists and renamed them augurs we'd be halfway to cutting their professional status down to size.

This is half-right. It's true that economists' cannot make accurate forecasts when we need them - a fact which predates the recent recession and recovery. And increasingly, we know why.

But it's also half-wrong. Economists have a lot to offer; there's much more to us than incompetent seers.

Here, though, economists have ourselves to blame. In making forecasts, we bring our profession into disrepute by giving laymen like Matthew the impression that our job is the futile one of forecasting when it's not. This means that we're not taken sufficiently seriously when we're right.

This has both a specific and a general cost.

The specific cost is that it gets the austerians off the hook. Matthew is inviting us to believe that Keynesians' failure to predict the current upturn discredits their criticism of austerity. But it doesn't. The proper Keynesian claim was not that austerity would prevent recovery, but that it would cause the economy to be weaker than would otherwise have been the case. Granted, this claim cannot be proved definitively by RCTs. But it is highly plausible because the mechanisms through which austerity might support the economy have been absent, and so Keynesian models have been more relevant than anti-Keynesian ones. It's because of the danger of conflating these two claims that I advised Keynesians not to forecast on-going recession.

The more general cost is that the failure to predict discredits economics more generally. Picture the scene. Jonathan is debating his correct view on immigration with some Tory. The Tory asks: why should we believe you when you didn't see the recovery coming? His reply is, of course, illogical, but it will have some plausibility with the unscientific layman.

You might reply that making a prediction is an essential part of any science, as it's a way of testing theories against data.

This conflates two different things - forecasting and prediction. A forecast is a description of the future which might go awry because of countless confounding factors; because of these, a wrong forecast might well not discredit the forecaster's theory. A prediction, though, is an implication of a theory which can apply to existing facts, if only we look for them. And economists can and do make many reasonably successful predictions, such as:

- The efficient market hypothesis predicts that actively-managed funds won't (pdf) justify their (pdf) high fees.

- Complexity economics predicts that economists generally won't forecast recessions succesfully.

- Behavioural economics predicts that overconfident investors will make mistakes.

What I'm saying here is, in truth, highly Keynesian. Keynes famously said that it would be "splendid" if economists could be seen as humble competent people like dentists. And whilst dentists can give warnings and advice, and fix some problems, they cannot foresee the future. And nor do they aspire to do so.

September 6, 2013

A capitalists' recovery

"Whose recovery is this?" asks Polly. The answer, I fear is: capitalists'.

I say so because of two reasonable suppositions.

First, that, as Duncan says, labour productivity might well recover as the economy grows. This could be because hitherto under-employed workers work more intensively as demand picks up. Or it could (eventually!) be because a recovery in bank lending to firms permits a return of the external restructuring that has traditionally driven productivity in the past.

Secondly, it's likely that high unemployment will continue to hold real wages down for a while to come.

This combination means that productivity could will rise faster than real wages, which means - ceteris paribus - that capitalists' share of GDP will rise at the expense of labour's share.

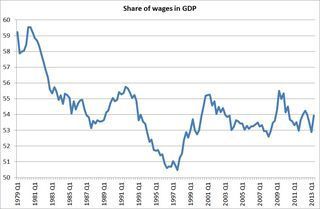

In truth, this is not so much a forecast as a description of what normally happens in upturns. During the recoveries from the recessions of the early 80s and early 90s, productivity rose strongly and the share of wages in GDP fell. Indeed, since 1979 there has been a significant negative correlation (-0.43) between five-year changes in the wage share and in labour productivity; faster productivity growth is usually accompanied by a falling wage share.

What would be the political impact of this? I suspect it would increase the popularity of demands for higher real wages, be it a living wage or - better still - stronger collective bargaining. This would be especially true if rising profits and share prices lead to some high-profile pay rises for "fat cats". This might explain why even some Tories are considering supporting a higher minimum wage.

But what of the feasibility of such policies? Much, I suspect will depend upon the strength of the recovery in capital spending. If this does bounce back strongly, the capitalist lobby will claim that the rising profit share is facilitating the recovery and so should not be jeopardized. If, on the other hand, capital spending stays weak - and the recovery is fuelled by, say, debt-driven consumer spending - the intellectual case for wage-led growth will strengthen, as it becomes more apparent that the rising profit share isn't stimulating capitalists' spending.

I'm not sure how this will play out. But it could be that the next few years (the General Election and beyond) sees class conflict becoming more salient in politics. Which would be awkward for those anti-Marxist ideologues who want to downplay the importance of class.

September 5, 2013

Managerialism & England's failure

Greg Dyke has set English football the target of winning the World Cup in 2022 - as if our failure in all tournaments since 1966 was because we weren't trying. This is witless managerialism. It's an example of exactly what Henry Mintzberg complained about:

All to often, when managers don't know what to do, they drive their subordinates to "perform". (Managing, p62)

And by his own admission, Dyke doesn't know what to do - which is why he's setting up a commission to investigate why there are so few English players in the Premier League. Worse still, even if he did know what to do, he wouldn't have the power to do it. The core of the team that wins the World Cup in 2022 will be in their mid-late 20s and so be late teenagers now. They should therefore be on the books of top clubs and making names for themselves. But are the likes of Ross Barkley, Phil Jones, Raheem Sterling and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain really sufficient to win a World Cup? If they're not, there's not much the FA can do because, as Dyke says,"The FA doesn’t control player development, the clubs do."

Sure, organizations occasionally succeed by setting big hairy audacious goals. But such goals only succeed if you have a roadmap for achieving them. Dyke doesn't.

Indeed, I suspect that winning the World Cup is the wrong sort of target for the FA. It should be focussing on improving the grassroots of the game, by giving small kids more and better coaching; Dyke rightly notes that England has fewer coaches than rival nations.

One thing such an improvement requires is a change in attitudes, in culture - putting more stress upon intelligence and technique rather than just passion and aggression. England has traditionally lacked the former: our equivalents of Pirlo or Xavi have been notably lacking.

Herein, though, lies a problem. Something as big as football reflects the culture of wider society. And our culture militates against top quality football. As I've said before, a society which has long been divided between white collar managers who do brainwork and blue collar grunts who do as they're told is the sort of society which is likely to produce physically strong players who inflexibly implement their managers' plans; think of Sam Allardyce teams. And it's not the sort of society which'll give us players of intelligence and technique necessary to win World Cups. Two things of which Englishmen have long complained - our lack of football success and the paucity of our skilled craftsmen compared to Germany - are related.

In this sense, Dyke is a symptom of the problem. Whilst managerialists like him have disproportionate influence in our society, we'll not win much.

Another thing: it could be that English football is shaped by the weather. But there's nothing Dyke can do about this either.

September 4, 2013

On wage-led growth

What's the relationship between capitalists' spending and the profit share? This sounds like an abstruse question, but it is key to the question of whether predistribution and wage-led growth are feasible.

I say this for a simple reason. Measures to raise wages, such as a living wage or stronger collective bargaining would tend to depress the profit share. There are two possible responses to this:

- If workers have a higher propensity to spend than capitalists, aggregate demand would tend to rise. This in turn could encourage capitalists to invest, in anticipation of that demand. If this happens, we'll get wage-led growth.

- If workers save their higher incomes their demand won't rise much. And capitalists might cut their spending in anticipation of this. This might be exacerbated if they regard better conditions for workers as a threat to the business environment.

Theory, then, is ambiguous, as it always is. My chart provides some evidence. It shows the coefficient on a simple regression of three-year real GDP growth on the profit share lagged three years, for rolling five year periods. A negative coefficient indicates periods of wage-led growth - a below-average profit share leads to above-average GDP growth.

You can see that, for most of the last 50 years we have indeed had wage-led growth; the coefficient has been negative. In most five-year periods, lower profit shares did lead to better growth and higher profit shares to lower ones. And this has been true in recent years - including before the crisis - which vindicates Stewart Lansley:

In both the UK and the US, booming profits have been associated with falling investment. This is because the sustained squeeze on wages has created a number of highly damaging economic distortions. It has sucked out demand, encouraged debt-fuelled consumption and raised economic risk.

However, wage-led growth is not assured. In the 80s and late 90s, the coefficient of GDP growth on lagged profits was positive; a high profit share improved business sentiment and unleashed sufficient capital spending growth to raise GDP nicely. And in fact, looking at the wholse sample (since quarterly data begin in 1955), the relationship between the profit share and subsequent GDP growth has been insignificant.

Of course, I'm only looking at two variables here; controlling for other things that affect GDP - which is probably impossible given that there are so many - might yield different results.

I'm not sure what to make of this. You could read it as evidence that wage-led growth is probably feasible. Or you could read it as a sign that it's a high risk strategy, as the link between profit shares and subsequent GDP growth isn't that robust. What makes me fear the latter is the possibility that higher wages might not boost spending, to the extent that they are either offset by cuts in tax credits, or lead to people paying off debt.

There are, though, some things a government could do to mitigate these risks, such as:

- Tax and benefit reform to reduce the marginal withdrawal rates low-paid workers face. A basic income, anyone?

- A greater socialization of investment, to reduce the risk of an investment strike.

- More active fiscal policy, to give capitalists' confidence that aggregate demand will stay high; this might have been one reason why wage-led growth was possible in the 50s and 60s.

Perhaps, then, wage-led growth is feasible if it is accompanied by other policies.

September 3, 2013

Heraclitus vs Zimbardo

Heraclitus or Zimbardo? That's the question raised by pictures of John Kerry and Tony Blair cosying up to Bashar al-Assad.

What I mean is that if Heraclitus was right and character is destiny then Kerry and Blair are, at best, lousy judges of character for befriending a "thug and murderer" and at worst mere hypocrites.

But there's another view - Philip Zimbardo's, that destiny is character, that what we do is shaped by circumstance and social structures:

Good people can be induced, seduced, and initiated into behaving in evil ways...Most of us can undergo significant character transformations when we are caught up in the crucible of social forces...Any deed that any human being has ever committed, however horrible, is possible for any of us - under the right or wrong situational circumstances (The Lucifer Effect, p211*)

This is consistent with Assad's tutor's memory of a "quiet, polite" man, and with Roger Boyes' account in the Times (£):

The idea was that Bashar with Asma at his side would not only de-brutalize the regime but modernize it...It did not work out like that, partly because of the US and British invasion of Iraq in 2003, partly because of the huge security machine that crushed reform and partly because so many of Bashar Assad's own clan profited from the system.

If you were to become a dictator overnight, faced with powerful lobbyists demanding violent repression and opponents determined to kill you, would you really remain a decent person? I fear an affirmative answer owes more to self-love than self-awareness.

On this view, Kerry and Blair are guilty not of misjduging Assad's character, but of underestimating the extent to which dicatorship degenerates into brutality under the wrong conditions.

Though Zimbardo's claim seems radical, it's quite widely shared across the political spectrum. When Warren Buffett said "‘When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for poor fundamental economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact" he was recognizing the importance of structure over individual character. The Marxian claim that people are bearers of social relations and the neoclassical claim that people respond to incentives similarly say that circumstances shape what we are.

You could read Adam Smith as saying the same thing. The belief that the invisible hand causes ordinarily self-interested people to promote general well-being amounts to a claim that the right social structures will overcome the impulses of bad or indifferent character. Isn't the obverse also possible - that the wrong structures can cause ordinary men to behave abominably?

The best-known experimental evidence here is, of course, the Milgram and Stanford Prison experiments. But there are other clues. There's evidence that measurable personality is as variable (pdf) as income. And whilst researchers have found some correlation between personality (pdf) features and economic outcomes, their explanatory power is quite low.

This issue matters for a simple reason. It's tempting to think that governments will be well-run if only good people were in charge - or failing that "our bastard". That's the Heraclitus view. But if Zimbardo is right, what matters isn't so much people as structures. If these are wrong, they can horribly warp the moral impulses of those in charge. As the man said, absolute power corrupts absolutely.

* I fear Zimbardo is exaggerating for effect here. There are some saints who'd do the right thing regardless of circumstance. The correlation between situation and "character" might be high, but it's not unity.

** Note for the hard of thinking: none of this is to excuse Assad's actions.

September 2, 2013

Gareth Bale & value theory

The question of whether Gareth Bale is worth €100m raises questions about the validity of marginal productivity theory.

Eamonn Butler writes:

In free markets, people pay us for the goods and services we produce because they value those products. So market rewards do depend, very directly, on the value that we deliver to other members of our society.

This ignores a crucial distinction - between actual, observable value and expected value. It's possible that Bale's value to Madrid will match his cost: for example, if he makes the difference between winning the Champions League and a quarter-final place in a single year, he'll be worth around £15m (pdf). But most of his transfer fee and salary, is determined by Madrid's expectation of his value. And it's quite possible that this will exceed Bale's actual value.

So how can Eamonn say that "rewards depend...on the value that we deliver"? One possibility is that he's talking about averages over the long-term. This is reasonable for many professions. If a company were to hire, say, electricians at £200,000 a year it would go bust because electricians don't create that much value. The excess supply of electricians would then bid their wages down to levels compatible with their value.

But this reasoning cannot apply in our case. When Sp*rs fans sang "there's only one Gareth Bale" they were - uniquely in their miserable lives - correct. It makes no sense to speak of the average fee of all Bales; Madrid are paying a fortune for him precisely because he's unique*. It might be that, averaged over all possible futures, Bale will be worth £30m a year - his fee and salary amortized over his six year contract. But this is unobservable and hence unscientific.

A more promising interpretation of Eamonn's comment is that, averaged across all footballers, wages equal value. Sure, some are overpriced and overpaid, but others - by the standards of the average footballer - are underpaid.

This claim, though, runs into an obvious problem. In aggregate, football clubs lose millions of pounds. Which is surely evidence that footballers, on average, are paid more than their average revenue product.

The objection to this is that revenue product is only part of value. We must add owners' non-pecuniary valuations - such as the gratification of their ego or the escaping of Russian politics.

But if we regard value in this sense, then Eamonn's claim becomes an untestable tautology. Whenever we see any worker or product changing hands at fancy prices, we can attribute it to some kind of "value." Sure, value's subjective. But it might be so subjective as to be unmeasurable. In fact, it's quite possible that the much-maligned labour theory of value is more scientific (pdf) than marginal productivity theory - insofar is it is both testable and, better still, compatible (pdf) with the evidence (pdf).

Here, though, we must draw a distinction between the validity of marginal productivity theory and the legitimacy of free market transactions**. It's quite coherent to argue that marginal productivity theory is silly, and yet defend market exchanges on Nozickean grounds that what consenting adults do should be their own business. Markets don't need to be value-maximizing to be legitimate.

* Bale is, in a sense a (near) monopoly, and monopolies charge a price above marginal product.

** I shall avoid the question of whether Madrid is operating in a free market.

Another thing: There are many complications here. One is that, in football, value is to a large degree zero-sum. Bale could justify his fee and salary by winning Madrid trophies. But if he does this, he's reducing the value of Barcelona players. Another is that, in team sports, an individual's marginal product depends upon complementarities with his team-mates; if these are favourable, his marginal product might seem big, and if their not it won't. This raises all sorts of issues.

August 31, 2013

Signaling problems

So far, nobody has pointed out that Miley Cyrus and Mark Carney have something in common, besides the same initials. Let me rectify this appalling omission.

The thing is, both have faced the same problem - of how to signal a break with the past, given their audiences' established priors.For Ms Cyrus, the problem has been to establish a break with her wholesome Hannah Montana image. For Dr Carney, it has been to show that the Bank is now more of a monetary activist, keen to use monetary policy to bolster the economy.

And both have faced the same twin dangers - of either under-signalling or over-signalling. For Ms Cyrus, an under-signal would have meant trading on her past and looking like a has-been. For Dr Carney, it would have meant not sufficiently changing rate expectations and hence the monetary stance. Equally, though, there's also been a danger of over-signalling: for Ms Cyrus, this lay in looking over-risque, for Dr Carney it meant the risk that a signal of low future rates is also a signal (pdf) of weak future activity, which could be self-fulfilling.

Herein, though, the similarity breaks down. Whereas Ms Cyrus has perhaps erred on the side of over-signalling - her performance at the VMAs has been widely criticised as sluttish, as if that were a bad thing - Dr Carney has under-signalled. As Andrew Lilico has pointed out, rate expectations have risen since he gave his "forward guidance" because the knock-outs gave markets the impression that the Bank actually cares about inflation.

I suspect their next major signals to reverse this pattern - for Miley to appear demure, in a "womanly" way, and (barring a postive growth surprise) Mark to dampen rate expectations.

If I had the expertise, I'd model this as an interated signaling game with the possibilities of the audience being non-Bayesian, either by over-reacting or under-reacting.

Instead, I'll make a cheaper point. It's that we should not, perhaps, criticise Dr Carney too much. To have made an effective stimulatory over-signal, he would have had to say: "The economy looks like recovering nicely, so don't hold back spending for fear of recession, but even so I'll not raise rates." But the fact that the inflation target still exists rules this out. In this sense, pop stars have fewer constraints upon their judgment than central bankers.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers