Chris Dillow's Blog, page 141

September 26, 2013

On political bias

Chris Giles in the FT says that, underneath the bluster, "the parties have rarely been closer on economics" - which is just what Hotelling's law and the median voter theorem predict. This raises the question: why, then, do political partisans pretend otherwise?

Some of the reasons are innocuous. Salesmen rarely claim there's little difference between their products and their rivals', and there are a host of cognitive biases - such as the optimism bias and groupthink - which cause them to oversell their own policies. And we might add to this the narcissism of small differences.

But there's something more subtle going on. There's a selection bias here. Most people who become interested in politics do so because they think policies matter. As a result, discussion of politics is disproportionately dominated by people who are prone to exaggerate the impact of policy.

Such talk, however, overlooks some important points. There's Adam Smith's insight that there's "a great deal of ruin in a nation" - that we can cope tolerably well with suboptimal policies (which is just as well). There's the evidence that national policies don't much affect trend GDP growth. And then there are the myriad structural and ideological constraints that limit what any government can do.

But here's the problem. This selection bias isn't just confined to political partisans. It also applies - generally speaking; there are exceptions - to political journalists (Chris, remember, is an economics writer). The guy who thought party politics was unimportant wouldn't become a political journalist in the first place, and wouldn't last long if he did.

In this sense, even journalism which aspires to be "neutral" is in fact biased. It's biased towards exaggerating differences: "clash", "row" and "deep divisions" are standard journalese. It's biased towards exaggerating the importance of such "divisions": how often do you hear Nick Robinson say "this doesn't really matter"? And it's biased towards giving the oxygen of publicity to those who think

party politics matters, and thus underweights sceptical voices like

Chris's.

These biases might be pernicious, insofar as they help to distract us from important facts - such as the possibility that, within capitalism, there's not often very much that any political party can (consciously?) do to transform the economy or society.

September 25, 2013

Neoliberalism's unintended consequences

One of the oldest rhetorical tricks of free-marketeers has been the appeal to unintended consequences; state interventions, they claim - often reasonably - don't work out as intended. But it's not just statist policies that are vulnerable to unintended consequences. So too is neoliberalism, as Ed Miliband's speech yesterday made clear.

That speech was an echo of Karl Polanyi. Back in 1944 he pointed out that pretty much all industrial societies had seen a retreat from laisser-faire and rise of statism since the late 19th century:

If [the] market economy was a threat to the human and natural components of the social fabric...what else would one expect than an urge on the part of a great variety of people to press for some sort of protection? (The Great Transformation, p150)

Miliband is betting on a repeat of this process. His talk of "one nation Labour" and his claim that the rising tide of economic recovery "just seems to lift the yachts" echo Polanyi's claim that market economies undermine the "social fabric". And his promises to freeze energy prices and strengthen the minimum wage are (mild) statist challenges to a private enterprise economy.

In this sense, we're seeing two unintended consequences of neoliberalism.

One, as Polanyi described, is that when market economies undermine human concepts of reciprocity - when the rich seem to get richer at the expense of the poor - they generate a backlash; Miliband's promise to freeze energy prices is hugely popular with focus groups.

The other is that this backlash is taking the form of statist policies. But this need not, in theory, be so. Historically, one alternative to statism has been the use of trades unions to protect workers; and yes, these are alternatives because as Philippe Aghion and colleagues have shown, stronger unions are associated with weaker minimum wage legislation. Sadly, the combination of weaker trades unions and the global excess supply (pdf) of labour rule out this alternative. Workers have lost power at the point of production, but they still have it in the ballot box, and Miliband hopes they'll use it.

Herein, though, lies a tragedy. In principle, unions are a better way of protecting workers than the state, partly because they represent "big society" virtues of self-help and community, and partly because collective bargaining can be sensitive to local idiosyncratic market forces in a way that legislation is not. But this healthy alternative is not available now.

In this sense, Miliband's rightist critics are missing a point - that his statism is an unintended consequence of the neoliberal policies they've supported.

September 19, 2013

The preferences problem

It's time we thought more seriously about the role that preferences should play in politics.

I'm prompted to say this in part by Yasmin Alibhai Brown's claim that many Muslim women are "brainwashed" into wearing the veil. It is improbable that it is only Muslim women who have subconciously adapted their preferences to acquiesce in their oppression and inequality. Experimental and ethnographic evidence supports Amartya Sen's view that this is true of the poor generally:

The deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation because of the sheer necessity of survival, and they may, as a result, lack the courage to demand any radical change, and may even adjust their desires and expectations to what they unambitiously see as feasible. (Development as Freedom, p63)

The question is: what political implication does this have?

At one utilitarian extreme, we might claim none. We should regard preferences as we regard sausages or land ownership, and not inquire too closely how they arise. If people's preferences are met, they'll be happy. Why worry if they are rational? To invert John Stuart Mill, better a fool satisfied than Socrates dissatisfied.

What lends this view credence is that it is hard to tell how a preference has arisen. All are endogenous in the sense of being a product of our culture and history; this is as true for liberal ironists as for niqab-wearers. It's patronizing and arrogant to pretend that we can discriminate against some preferences.

On the other hand, though, as Daniel Hausman has argued, preferences have no moral status except insofar as they are evidence of what's good for us - and there's increasing evidence, even aside from the problem of adaptation, that this is only sometimes the case.

I'm ambivalent here. And so too is our political culture. On the one hand, great weight is put upon preferences: radio phone-ins, vox pops, opinion polls, and comments sections all elevate the status of opinion, however ill-informed.

But on the other hand, there's a tradition of limiting the role of preferences. Some laws protect us from ourselves; we can't sell ourselves into slavery, sell an organ or possess some narcotics. For Rawlsians, the basic structure of society should be determined by the ideal preferences we'd have behind a veil of ignorance rather than by actual preferences. And human rights laws, to the consternation of the trash press, limit what can be done by popular will.

The question is: when and how do we decide when preferences should determine policy and when not? When should the Burkean legislator exercise his independent "judgment" to over-ride his constituents' opinion?

One answer - and a justification for human rights - stresses the importance of vital interests. Some of our interests, such as the right to speak or to family life, are so important that they must be protected against the popular will. But I'm not sure there are bright lines here. One could argue that the poor have a vital interest in having their lot improved, even if there's little public demand to do so. If so, then justice - "the first virtue of social institutions" as Rawls called it - trumps democracy. But this puts us on a slippery slope to Leninism.

Now, I say all this because I'm confused, and I suspect many others are too. Our political culture has not yet begun to answer the questions posed by the growing evidence that our preferences don't necessarily coincide with our interests. And this, I suspect, has contributed to the problems politicians have - that they can't decide whether to be populists or technocrats and so end up being neither.

The fairness error

There's one reaction to Nick Clegg's proposal to give free school meals to all young children that is both wrong, and reflective of a wider error.

I'm referring to the notion that it is somehow unfair for the rich to get a benefit as well as the poor. For example, Isabel Hardman says the policy means "giving a £400 annual saving to mothers who are perfectly capable of sending their children to school with smoked salmon sandwiches in their packed lunches." Iain Martin says its "strange" that a benefit should be given to kids "regardless of their parents income." And the IoD says "You need to focus on the people who really need help."

The general error here, of which these reactions are specific examples, is the belief that we should judge the fairness of policies one-by-one. We shouldn't. What matters is the fairness of the overall system, not of individual transactions. As Nick Barr says in the standard textbook on the welfare state:

It is frequently the overall system which is important...Taxation and expenditure should be considered together. (The Economics of the Welfare State, p185, his emphasis)

For example, is it fair that the poor should pay the same rate of VAT as the rich? Is it for that matter fair that they should pay the same prices in Tesco as the rich? Maybe not. But fairness is not the only virtue. Efficiency also matters. Just as it would be absurdly inefficient for Tesco to assess folks' income every time they went to the checkout, so it would be inefficient to means-test all benefits. The inefficiencies take at least two forms. There's the deadweight cost of the bureaucracy required to assess eligibility. And there's the disincentive effects created by those benefits being withdrawn as the individual's income rises.

Given these costs, universal benefits are more efficient. This is especially true for free school meals, which might well have favourable supply-side effects by raising pupils' ability to learn.

If you think such benefits flow too much the wealthy, the solution is not to means-test the benefits themselves, but to tax the rich more. As I say, we should judge fairness at the macro level, not the micro one.

My point here isn't confined to free school meals; it applies equally to child benefit, winter fuel payments and the like. And Ms Hardman is right to point out that Lib Dems attitudes here have hardly been consistent.

Although leftish social democrats have traditionally been most keen upon universal benefits, this should not really be a left-right issue. The left can argue for high universal benefits and high taxes, the right for lower ones - perhaps emphasising the disincentive effects of high benefit withdrawal rates. The only case for supporting means-testing is that you care less about efficiency and more about stigmatizing and vilifying the poor.

September 18, 2013

Inflation and real incomes

There's one widespread reason for optimism which I think is worth questioning. It's the idea that a fall in inflation next year will help to reverse the fall in real wages and so raise real households' incomes.

First, let's check the data. Since 1949 - when current records began - the correlation between annual inflation and annual growth in real personal disposable incomes has been minus 0.31. This seems to support the optimists' case; lower inflation is associated with higher real incomes.

However, much of this correlation is due to the mid-70s period, when a soaring oil price cut the real incomes of oil-consuming nations - a process exacerbated by the government's attempt to use wage control to fight inflation. Since 1980, the correlation has been a statistically insignificant minus 0.15.

There's a good reason why the correlation should be insignificant. It's that inflation has ambivalent effects upon real incomes.

If inflation falls because of a positive supply shock - such as a drop in commodity prices - then we would expect to see real wages and incomes rise.

However, if inflation falls because of weaker aggregate demand, then labour demand will be weak, which will hold down real incomes. Between the late 80s and the early 90s, for example, inflation fell but so too did income growth, precisely because of that weak demand.

Which brings me to our current predicament. There's no good reason to suppose that commodity prices will fall except because of random noise; remember Hotelling's rule? We cannot therefore bet on this source of a negative correlation between inflation and real income growth asserting itself. Granted, we could get the positive supply shock of a return to productivity growth, but this is more likely to benefit capitalists than workers in the first instance.

However, it's quite possible that inflation will fall because of weak aggregate demand and excess capacity. But these are conditions in which real wages won't rise much and might even continue to fall.

In saying all this, I'm not ruling out a recovery in real incomes next year; I know nothing about the future. It's just that if you want to contend that this will happen, you should simply contend that aggregate demand - and with it workers' bargaining power - will pick up briskly. Leave inflation out of it.

September 17, 2013

Accepting inequality

Why aren't voters more concerned about rising inequality? For example, in the UK since the mid-80s, the share of income going to the top 1% has risen from around 8% to over 13%. But during this time the proportion of people agreeing that the government should redistribute income has fallen slightly - with larger falls among younger and working class people.

It could be that this tolerance of inequality reflects an acceptance of neoliberal economics. People are now more inclined to believe that "wealth creators" need high incentives to work hard, and that as they do so we all become richer, so inequality is in our self-interest.

However, new experimental evidence rejects this possibility.

Kris-Stella Trump got subjects to compete in pairs to solve the most anagrams in four minutes. The pairs were randomly divided so that in some pairs the winner got $9 and the loser $1 whilst in others the winner got $6 and the loser $4.However, unknown to the subjects, the competition was rigged so that they always narrowly lost to one of Dr Trump's colleagues. After the game, the losers were asked how they would have divided the prize money. And here's the thing. The losers who got $4 thought it fair a fair split was (on average) $6.15-3.85 but the losers who got just $1 thought a fair split was $7.77-$2.23. In other words, actual inequality shapes our perceptions of fairness. Dr Trump says:

Public ideas of what constitutes fair income inequality are influenced by actual inequality: when inequality changes, opinions regarding what is acceptable change in the same direction.

There are two reasons for this, says Dr Trump. One is the status quo bias; a form of anchoring effect causes us to accept actually existing conditions. The other is the just world effect. We want to believe the world is fair, and if we want to believe something, it's very easy to do so. This is the system justification theory described (pdf) by John Jost and colleagues. There is, they say, "a general psychological tendency to justify and rationalize the status quo" which is "sometimes strongest among those who are most disadvantaged by the social order."

All this corroborates my Marxian prior, that inequality generates cognitive biases - ideology - which help to sustain that inequality.

And this in turn poses a challenge to democratic egalitarians. If this is right, the fact that there's public support for - or at least acquiescence in - inequality is no evidence whatsoever for the justice of that inequality. It might be, therefore, that we cannot achieve justice by democratic methods.

September 16, 2013

Recovery for whom?

Everyone agrees that the economy seems to be recovering. So what?

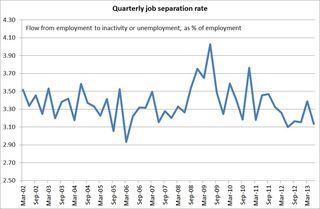

I ask because a recovery does not mean that everyone gets better off. Just as millions of people keep their jobs in recessions, so thousands lose theirs even in good times. My chart shows the point. It shows the quarterly job separation rate. I define this as the numbers moving from employment to either unemployment or inactivity in a three month period, expressed as a percentage of the previous quarter's stock of employment. Even during the good times of 2002-07, this rate averaged over 3% per quarter. This implies that the average worker in decent times has a greater than 3% chance of not being in work three months later. The risk is higher for younger or less educated workers.

Now, this is an imperfect measure of job insecurity. On the one hand, it overstates it because it includes people leaving jobs voluntarily, for example to retire or have children. But on the other, it understates it to the extent that it ignores people who lose their job and get a new one within the same quarter.

Another measure of job insecurity is the redundancy rate. This averaged 0.6% per quarter in 2002-07, but rose to over 1% in the recession. This, though, understates job insecurity, to the extent that workers can be eased out of jobs without being formally made redundant.

What this means is that, even though the recession is over, many workers still face a significant risk of unemployment. And this, remember, means not just a huge loss of income, but also considerable unhappiness.

Two other facts corroborate this - that between 1997 and 2008 an average of 47,000 jobs (pdf) were lost per week; and that official data show that between 2002 and 2007 an average of around 10% of businesses ceased trading each year.

I say all this as a counterweight to the statistical fetishism which obsesses with noisy quarterly GDP data but ignores the insecurity which many people face even in normal times. Economics, it is often forgotten, is about people, not numbers.

In this sense, the economic debate misses something important. The question is not just: how can we achieve macroeconomic stability? It is: are we doing enough to cushion individuals from microeconomic volatilty and idiosyncratic risk?

I'm not at all sure we are.

September 15, 2013

Celebrity

The news that Nadine Dorries has got a lucrative book deal casts more light upon the economy and society than generally realized.

What Ms Dorries is doing here is just what Chris Huhne is doing writing for the Guardian and Rylan Clarke did in presenting Celebrity Big Brother. All - like many former MPs - are using the celebrity or notoriety obtained in one sphere to make money in another. Many people, such as Katie Price or Pippa Middleton, make a life of this. Celebrity is a general purpose technology.

One big reason for this is that celebrity saves on marketing costs. If a publisher discovers a brilliant but unknown writer, it must spend a fortune promoting her. Ms Dorries advertises herself.

In this context, asking whether Ms Dorries is a good writer is a category error, as daft as asking whether Vanessa Feltz can dance. The point of hiring Dorries, Feltz or Huhne is not to bring quality, but attract attention. When Huhne wrote an epically unself-aware piece for the Guardian, a complaisant Twitterati made him trend - which is precisely what the Graun hoped.

Herein, though, lies an important social change. Everyone loves to gossip. A few decades ago, they did so like Cissie and Ada, about neighbours and acquaintances. In our more atomized society, though, this is less possible. So we gossip about celebrities instead.

But which ones? Say we want to talk about a singer. If I want to talk about Jolie Holland and you about Natalie Williams, we get nowhere. So we talk instead about Miley Cyrus. Ms Cyrus is in this sense a Schelling point - the solution to a coordination problem. It does not follow that Ms Cyrus is a better artist than Ms Williams or Ms Holland, any more than that its "better" for us all to drive on the left than on the right. She's just what we coordinate upon. It's the same for Ms Dorries. She is profiting from the breakdown of community that causes us to gossip about people like her rather than neighbours.

This gossipability, though, can be leveraged to sell songs or books or TV appearances, which in turn generates more gossip and more marketability. In this way, as Moshe Adler has described (pdf), someone of no more ability than others can become a superstar.

In Adler's model, people can become stars even though they have equal talent to other, more obscure people. I would add that ability and integrity might even be a handicap. If we prefer to talk about people whom we believe to be our inferiors, then second-raters and crooks will have an advantage in acquiring gossipability, celebrity and the wealth that follows.

Now, I don't think we should complain too much about this; the same process that gives Dorries her book deal also puts Rachel Riley on Strictly Come Dancing. But it does reinforce Hayek's point, that in a free market, "the return to people’s efforts do not correspond to recognizable merit." A market economy is not, and cannot be, a meritocracy.

September 14, 2013

On path-dependent beliefs

Imagine someone were to say that Tory incompetence and mendacity were a major threat to Britain's position in the world, and that the Suez crisis proves just this. You'd think them mad: that debacle has no relevance to today's politics.

However, according to Matthew Parris in the Times, many Tories have such out-dated attitudes to unions. He says they believe they benefit from Labour's "indefensible" links with unions:

They know the toxic potency in millions of minds of the image of the raised fist of organized labour. With relief they sink into the comforting upholstery of a ready-made rhetoric about trade union barons, winters of discontent, beer and sandwiches and No 10, union militants...

For millions of voters, though, the winter of discontent is as distant from their lives as the Suez crisis is to mine. There'll be voters at the next election whose parents weren't born in the winter of discontent. And many first-time voters in the 1979 election are now retired.

What's more, it's perfectly arguable that our problem today is not overly powerful unions, but overly weak ones. Stronger collective bargaining which causes a shift from profits to wages might well be a good macroeconomic strategy.And even conservatives should support unions because they are an example of Burke's little platoons and a healthy alternative to state regulation.

In this light, it's no surprise that the public is not especially hostile to unions.

Which poses the question. Why, then, do Tories like the "comforting upholstery" of anti-union rhetoric?

One possibility is the false consensus effect; we tend to exaggerate the extent to which others share our beliefs.

Another (not exclusive) possibility is that beliefs can be path-dependent; we believe things because we used to, and continue to do so even after such beliefs have lost truth-value or utility. What's more, I suspect this path-dependency can sometimes be transmitted from generation to generation. So, for example ethinic minorities are very unlikely to vote Tory, in part because of memory of the party's racist past; Greeks dodge taxes because of the legacy of Ottoman rule; and Germans are hostile to inflationary policies because of memories of Weimar hyper-inflation. Perhaps Tory antipathy to unions falls into this class of beliefs - a form of folk memory that is no longer useful. We are all prisoners of history.

September 12, 2013

Advise whom?

To whom should economists offer advice? Traditionally, the answer has been: politicians.But I'm not sure this should be so.

This isn't just because economists can't foresee the future and so a lot of advice on monetary and fiscal policy is pointless.It's because policy is shaped not by what is the right thing to do, but by what politicians can sell to inattentive and sub-rational voters. Whatever else informs immigration policy, for example, it is not economic research.

Of course, economists do sometimes influence policy for the better - auction theory being a good example - but this happens only when economic ideas don't rub too harshly against prejudice and vested interest. Otherwise giving policy advice is, to paraphrase Robert Heinlein, like teaching a pig to sing: it wastes your time and it annoys the pig.

I suspect that, insofar as economic ideas do influence policy, it is often through the lengthy and subtle process of changing the intellectual climate - as free-marketeers did in the 60s and 70s - rather than through advice leading directly to policy.

This, though, doesn't mean economists shouldn't or can't give advice. We can - to "ordinary" people*. It's often said that "max U" economics is at least as much a normative theory as a positive one. Which suggests that there is a role for economists in helping people make everyday decisions. This role is enhanced by the fact that a lot of the best recent research in economics has been in precisely how individuals' decisions often do fall short of rational maximization. It's rather sad that many economists' reaction to the cognitive biases research programme has been: how can we use this to give policy advice (eg nudge)? when it could equally be: we can use this to help people improve their everyday decision-making.

Granted, most of the financial advice you'll ever need would fit on an index card. But, hey, repetition is the mother of learning. And the need for impartial advice is perhaps exacerbated by the fact that a lot of the advice proferred by the financial "services" industry is self-serving crap.

In truth, I'm talking my book here. A fair chunk of my day job is being like an agony aunt; I'm more like Marje Proops or Abby van Buren than Stephanie Flanders. If economists want to become like dentists - as Keynes hoped - they should deal less with politicians and more with real people, both in advising them and learning from them.

* I hate the phrase "ordinary people"; most of our rulers - in politics and business - are far more ordinary than "ordinary people." I wish I could think of an alternative.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers