Chris Dillow's Blog, page 136

November 23, 2013

The ballad of Kostas & Jurgen

We should distinguish between macro- and microeconomic failure. That's the lesson I take from this exchange between Frances and Tim.

Let's use Tim's barbecue metaphor. Comparative advantage requires that the idiot cousin - call him Kostas - does something mundane like shape the beef patties, whilst the skilled cook - call him Jurgen - does fancy things with the barbecue.

However, this might mean that Kostas doesn't have much to do. This'll be especially the case if Jurgen's on a diet and doesn't want to eat much.

There's a danger, therefore, of Kostas getting into trouble. Worse still, if Jurgen insists that Kostas only eats as much as he contributes to the barbecue, Kostas will be ill-fed.

What can we do about this?

We could plonk him in a deckchair and ply him with Pimms. But Jurgen hates idleness and doesn't want to see his Pimms go down the gullet of layabouts. Sure, his feelings are irrational. But he's a stubborn fellow and there's no shifting him.

Instead, Kostas might be able to beg for other menial jobs, but there's no reason to suppose this will be enough to keep him employed.The idea that people can get work if only they accept sufficiently demeaning conditions is a just-so story without historical or theoretical foundation.

Alternatively, Kostas could leave the barbecue. But it's not obvious he'll find a better one, and even if he can, the bus fare to get there will be expensive, and Jurgen might have to help pay it.

Instead, there's a simple answer here - to have a bigger barbecue. If Jurgen came off his diet and ate more burgers, there'd be more for Kostas to do.

The problem with our barbecue, therefore is a macro one, not a micro one. Jurgen and Kostas are doing the right jobs; there's no failure of comparative advantage. The problem is simply that the barbecue isn't big enough. What we have here is exactly the problem Keynes identified:

I see no reason to suppose that the existing system seriously misemploys the factors of production which are in use...When 9,000,000 men are employed out of 10,000,000 willing and able to work, there is no evidence that the labour of these 9,000,000 men is misdirected. The complaint against the present system is not that these 9,000,000 men ought to be employed on different tasks, but that tasks should be available for the remaining 1,000,000 men. It is in determining the volume, not the direction, of actual employment that the existing system has broken down.

Now, in saying this I don't mean that the theory of comparative advantage is correct. It isn't. There's less (pdf) trade in some ways than the theory predicts, and more trade within industries and between neighbouring countries. Some guy got a Nobel in 2008 for analyzing these issues.

What I do mean is that we don't need to reinvent the wheel. Some problems have a simple economic solution, and are not a sign that conventional economics is wrong. The problem with our barbecue is one of morality more than economics.

November 22, 2013

The journalist's fallacy

The journalist's fallacy is the name I gave to the habit of drawing strong inferences from only one or two data-points. We've seen two nice examples of it this week, from left and right.

From the left, we have Seamus Milne. He points to Manchester University students who are campaigning for a more pluralistic economics curriculum as a sign that "orthodox economist have failed their own market test. Granted, he could have widened the evidence base; there's a similar movement at Cambridge, at least. But he omits two facts:

- Demand to study ("orthodox") economics at university has risen 33% in the last six years, whilst applications to university generally are up by only 19%.

- At least two universities - Oxford and Manchester; I know coz I took 'em - used to offer courses in the history of economic thought, but dropped them in part for lack of demand.

These two facts suggest that demand for "orthodox" economics is strong. It's too damned strong in my book, but things are as they are, not as we'd like them to be. (And anyway, the truth or not of "orthodox" economics is not to be decided by what undergraduates think.)

From the right, we have Melanie Phillips' attempt to tell us that the Paul Flowers affair tells us something about the broader liberal-left. But she doesn't point that many Labour and Coop members are not financially illiterate drug-takers, nor that - perhaps! - some on the right might be. She doesn't even try to fill in the Bayesian boxes. Granted, she might have cited Hayek's "Why the worst get on top", but that could apply - as he says - to "any society."

There are thousands of coops in the UK, and only one (or a few) Paul Flowers. The question - which is of fundamental importance - is: are coops more efficient than capitalistic firms? This cannot be settled merely by pointing to any individual personal failure, but by wider statistical research.

Seamus and Melanie are committing a similar error. Both are inferring too much from individual examples - an error exacerbated by wishful thinking. They are neglecting the very useful advice offered in this great piece in nature - that "data can be dredged or cherry picked."

Now, you might object here that pointing out that Seamus and Melanie have limited powers of ratiocination is the epitome of lazy blogging. It is, but there's a more general point here. It's that Seamus and Melanie have successful journalistic careers whereas I don't. One reason (of several!) for this is that the lively human interest anecdote is more vivid and interesting than dull statistics; admit it, you'd rather read about Flowers' porn habit than about the relative productivity of worker- versus capitalist-owned firms. And journalism is about giving readers what they want, not about high-minded logic and evidence.

All of which makes me suspect that Noah Smith might have added something here.

November 21, 2013

The (non) politics of stagnation

Aside from the allegations of sexism, Larry Summers and Russell Brand don't seem to have much in common. But they do. Summers' talk of secular stagnation corroborates the idea that politicians are out of touch not just with voters but with reality.

The thing is, there is nothing much new in what Summers says. Ben Bernanke's famous "investment dearth" speech was made eight years ago, and UK firms' capital spending has been lagging behind retained profits for over a decade. The lack of investment which lies behind sluggish growth is an old problem.

But it's one our political class barely discusses. Tories seem unaware that the stagnation of the pre-recession years refutes the notion that lowish taxes and a quiescent workforce are sufficient to boost investment. And Labour and - more bizarrely still some of the broader left - seem to think austerity is the cause of our problems rather than an exacerbating symptom of them. The question: "what if trend growth is very low?" doesn't seem to be on the agenda.

What if it were? The answers, I suspect, would fall into two sorts.

One would be to pay more attention to ways of increasing trend growth. These might include supply-side socialism, a greater socialization of investment and perhaps bigger government. They would also include - as Duncan stresses - policies which ensure that companies are run for the long-term, rather than in the short-term interests of rent-seekers.

However, the fact that national long-run growth rates have not been greatly affected by government policies in the past warns us that such measures might not be enough.

Which leads to the second set of questions: if we are stuck in low trend growth, how can we minimize the pain of this? Questions of how to achieve efficient redistribution, and how to pool economic risks thus become more important. Basic income, anyone?

But the mere raising of these issues only shows that there's a massive gulf between the petty preoccupations of the political class (which includes the mainstream media) on the one hand, and the scale of our economic problems on the other.

For a long time, mainstream party politics has assumed that the private sector will deliver decent long-run economic growth if only it can get the right conditions. The possibility that this assumption is wrong is one the political elite doesn't seem much interested in. As Mr Brand said, the political system is apathetic to the needs of the people.

November 20, 2013

The responsibility paradox

Many people are averse to taking responsibility. That's the message of some new research led by Georg Weizsacker. He and his colleagues show that many prefer to randomize their choices rather that make them themselves even if doing so reduces expected utility. This is true not just in laboratory experiments but in important real-life choices such as university applications. This, he suggests, is because people are regret-averse; they fear they'll kick themselves if they make a wrong choice, and so choose randomness to minimize such regret.

This finding is consistent with two big political absences - that there's little demand for greater worker democracy, despite evidence that this might be more efficient than more hierarchical firms; and that there's little demand for direct democracy despite evidence (pdf) that it can improve well-being.

Perhaps an (irrational) aversion to responsibility explains these absences; as I said yesterday, the problem with democracies isn't politicians so much as voters.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. Whilst people seem happy to shun responsibility in at least some spheres, there is no demand for the explicit introduction of deliberate randomness into public affairs. For example, there are no calls for sortition, even though it has some advantages; see Jon Elster's Solomonic Judgements for a longer discussion.

There is, I fear, a simple solution to this paradox. Whilst people don't want responsibility for themselves, they are keen to hand it to others rather than accept dumb luck. It could be that our desire for bosses - in politics and at work - arises from the same motive as the desire for a planned economy rather than the chaos of the market, or the belief in God. They are all examples of an urge that someone take responsibility rather than that we rely upon impersonal forces. Humankind cannot bear very much randomness.

November 19, 2013

Irrational voters

Sevenscore and ten years ago today, Abraham Lincoln coined the phrase "government of the people, by the people, for the people." He omitted to add that the people can be systematically wrong, as a new paper neatly shows.

Michela Redoano and colleagues estimate that, in the UK, women whose husbands died in the previous two years are 10-12% less likely to vote for the government than other women. There's a simple reason for this. The less happy people are, the more likely they are to vote for opposition parties; this is a variant of the affect heuristic. But people don't distinguish fully between being unhappy and being unhappy because of bad government. As a result, they - in effect - blame the government for things it is not responsible for.

This is not an isolated finding. Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels have found (pdf) that voters, in effect, blame governments for things they cannot control such as natural disasters. And Neil Malhotra and colleagues show that surprise victories for the local team in US college football games increase support for incumbents in gubernatorial, presidential and senatorial elections. This is consistent with the fact that Harold Wilson blamed Peter Bonetti for losing him the 1970 general election.

I suspect that UK governments have long tried to exploit this misattribution effect.One reason why they prefer to hold elections in the spring is that lighter nights improve our mood, which makes us better inclined towards incumbents. It's no accident that the preferred month to hold general elections - May - is also the month in which share prices often peak.

You might object that the bias from this source is small. Maybe. But if voters are irrational in this respect, isn't it likely they'll be irrational in others. It's insufficiently appreciated that the problem with democracy is not just the shortcomings of our politicians, but those of the voters too.

November 18, 2013

In defence of Help to Buy

Pretty much everyone, including me, agrees that Help to Buy is a lousy idea. So, in the spirit of a lawyer defending a psychopath, let me try to defend it.

In part, Help to Buy is a deficit-reduction strategy. Insofar as the scheme encourages the private sector to run a smaller financial surplus, the counterpart to this is a decline in government borrowing; financial balances must sum to zero. This in turn helps relieve the (self-imposed) constraint upon fiscal policy, which makes tax cuts or spending rises more feasible. We can use higher stamp duty revenue to cut tax for the low-paid.

You might reply that it would be better to encourage corporate borrowing. But we've tried this with the Funding for Lending Scheme, and yet borrowing by small firms is still falling. There's a reason for this. The dearth of investment opportunities means companies just don't want to invest - hence the talk of a "new normal" or "secular stagnation." What's more, even if we could revive manufacturing, it's not obvious this would help much. Thanks to globalized supply chains, this would suck in imports, and give our mediocre manufacturing base, we'd soon run into skills shortages.

There's another objection to the scheme that's questionable. Andrew Gimson warns of the dangers of encouraging people to become over-geared. But whatever happened to the Tory idea that people are the judge of their own best interests? It's quite possible that more people are credit-constrained than are irrationally over-optimistic. If so, then on balance Help to Buy moves folk closer to optimal debt levels.

Nor is it obvious that Help to Buy is stoking a bubble. Outside of London, house prices in nominal terms are lower than they were at the end of 2007. And as Mark Carney said last week, policy shouldn't be made only for people living within the Circle Line. But so what if we do get a bubble that subsequently bursts? As Daniel Gross has argued, bubbles have have lasting positive effects. If a bubble triggers more housebuilding, that's good.

There's another objection that won't do. Nick says the scheme will create "a client state of bribed voters", as if this is a bad thing. But let's face facts. All governments try to do this; elections are won by appealing to interests, not ideals. And you could argue that a constituency with an interest in keeping interest rates low is desireable. These will prefer a policy of fiscal conservatism and monetary activism. Such an anti-Keynesian base will tend to have an antipathy to big government. And given that it's possible that a small state is favourable to growth, this will create the conditions for long-run growth.

Now, I don't argue all this because I believe it - though my beliefs don't matter. My point is rather that if you are an anti-Keynesian with a desire to shrink the state and a pessimism about the investment oppotunities facing the private sector, then Help to Buy has something to be said for it. Maybe it is a symptom of our problems, rather than merely an idiotic idea in itself.

November 17, 2013

The economic base of illiberalism

One of the oldest divisions on the left - expressed by thinkers ranging from Merle Haggard down to Maurice Glasman - has been that between a liberal "metropolitan elite" and a socially conservative working class. Some new research validates the Marxian theory that this divide has an economic base.

Marko Pitesa and Stefan Thau first manipulated subjects' perceptions of their income by inviting some to compare themselves to high incomes ($500,000 per month) and others to low incomes ($500 per month). They found that people primed to believe they had low incomes then expressed harsher judgments about violent acts than those who were primed to think themselves rich.

This, they say, supports the idea that when people feel themselves to be poor, they feel more vulnerable to others' harmful acts, and this caises them to make harsher judgments about them. If you can afford to replace your iPod you'll be less censorious of muggers than if you can't. If you're driving your children around all the time, you'll be less hysterical about paedophiles than if your kids have to walk everywhere. And so on.

Thanks to the work of Ben Friedman, we should know by now that economic insecurity creates intolerance. This paper provides experimental evidence of microfoundations for this. That's progress.

Now, we should distinguish here between the extent of illiberal opinions and the intensity of them. Surveys suggest that working class folk aren't much more opposed to immigration, drug legalization or gay marriage than richer people. But this is quite consistent with them having more intense feelings. Gillian Duffy's antipathy towards immigrants is, sadly, shared by the middle class; the difference is the vehemence with which those opinions were expressed.

I say all this to make two points.

First, moral judgments are influenced by our economic positions. Marx was right to say that "the mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life." For more evidence of this, consider Matteo Cervellati and Paolo Vanin's discussion of how moral norms are shaped by family wealth.

Secondly, when liberal leftists complain about working class illiberalism, they should remember that the failing here lies not (just) with the working class themselves, but in social democracy itself. This has - so far - failed to sufficiently reduce the sense of vulnerability among the poor which produces illiberal attitudes.

November 16, 2013

Gove vs Cowell: an old dilemma

Michael Gove says Simon Cowell is "irresponsible and stupid" to say that the key to success is "to be useless at school and then get lucky." Who's right?

In one sense, Gove is. Everyone agrees that, on average across all people, those who do better at school - getting A levels or degrees (pdf) relative to just GCSEs (pdf) or nothing - tend to earn more.

Sure, there are a few exceptions to this. And it's possible that doing badly at school might even cause some people to do well in later life - say, if they want to prove their teachers wrong. But these are a minority.

However, Cowell is correct to say that luck matters. We know this because (observable) personal characteristics account for only a fraction of the variation in earnings. Even allowing for the subject and class of degree, variations in qualifications account for a quarter or less of variation in earnings. Even if we add measurable aspects of personality (the big five factors), this proportion rises only to around two-fifths (pdf).

Of course, this could tell us that unobservable characteristics matter. But, by definition, we can't test this.I suspect instead that it tells us that luck is important. Surely anybody with an atom of honest self-awareness knows this; I can easily imagine that, with slightly circumstances, I would be much poorer or much richer than I am.

In this sense, Cowell's right.

But it doesn't follow that Gove is wrong to call him irresponsible. There's a difference between truth and utility. Telling youngster that luck matters might be true, but it could cause them to work less hard thus jeopardizing their chances in life. Inculcating the false belief that hard work and talent is all, on the other hand, might motivate them to do well.

No less a person than Hayek was awake to this dilemma. On the one hand, he wrote:

The relative position of all the members of a particular trade or profession compared with others will more often be affected by circumstances beyond their control and knowledge. (Law, Legislation & Liberty vol II p73)

But on the other:

It certainly is important in the market order...that the individuals believe that their well-being depends primarily on their own efforts and decisions. Indeed, few circumstances will do more to make a person energetic and efficient than the belief that it depends chiefly upon him whether he will reach the goals he has set himself.

He concludes:

It is therefore a real dilemma to what extent we ought to encourage in the young the belief that when they really try they will succeed, or should rather emphasize that inevitably some unworthy will succeed and some worthy fail.

The row between Gove and Cowell reflects different views on the solution to this dilemma.

November 14, 2013

The social mobility chimera

David Cameron says "there's not as much social mobility as there needs to be." I wonder why he believes this, because some of the apparently plausible reasons don't bear inspection. For example:

"Social mobility is a measure of a just society." It needn't be. Imagine a dictator who imprisons his subjects, but gives wealth and power to some chosen at random. There'll be a lot of social mobility, but no justice or liberty. The test of a just society lies in the actual lives led by people - or by the worst-off if you're a Rawlsian - not by the chances they have. I'd rather live in a free, wealthy and moderately egalitarian society without social mobility than an unfree, poor and unequal one with it.

"Efficiency requires that we get the best people into top jobs." This is doubtful. For one thing, social mobility might worsen the quality of leadership. People who rise from humble backgrounds to "top jobs" might well become overconfident about their abilities and so prone to reckless decision-making. If your looking for poster boys for social mobility, you could do worse than Fred Goodwin, Hank Greenberg or Charles Prince. And for another thing, it could be that the problem with many organizations isn't that they are led by duffers but rather than they simply cannot be managed well from the top-down because they are inherently complex, or because hierarchies naturally demotivate employees. If so, it might be more efficient to restructure organizations so they become less dependent upon scarce "leadership" "talent."

"It's only fair that people get an equal start in life." This, though, is a utopian fantasy; you can't equalize the quality of parenting. And we shouldn't see life as a single race. Many people don't want to compete, but rather want to lead a modest life well. For these, the problem isn't a lack of social mobility so much as low wages, job polarization and the slow death of the goods of excellence. As Will says, rather than pursue a fictional equality of opportunity, we should have many spheres in which people can thrive by different standards.

In saying all this I don't mean that people should know their place. I'd rather have an egalitarian liberal society and let social mobility fall as it will. It should be a by-product of a good society, not an end it itself.

So, why does Cameron appear to think otherwise? Here's a conjecture. He wants social mobility for the same reasons that Michael Young - coiner of the word "meritocracy" - didn't. If we had equal opportunity, rich and poor would both feel that they deserved their place. In this sense, social mobility can be used to legitimate inequality.

November 13, 2013

On labour market flows

How much do the unemployment figures tell us? The Bank of England thinks the answer is: quite a lot - hence its use of the unemployment rate as an intermediate threshold. But I'm not so sure.

By this I don't mean just that there's huge amounts of hidden unemployment. Today's figures show that there are 2.3m "economically inactive" people who'd like a job, and 1.46m part-timers who'd like full-time work. And this is not to mention full-timers who'd like more hours.

Nor do I just mean that there's sampling error in the unemployment numbers. The ONS puts this at 87,000. This means we should understand today's news that there are 2.47m unemployed as meaning there's a 95% chance that the number of unemployed - on the LFS definition - is between 2.38m and 2.55m.

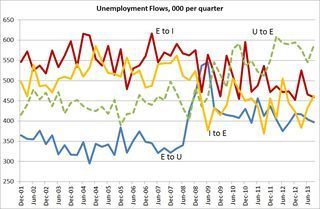

Instead, I'm thinking of the data on labour market flows. The ONS puts people into three categories: employed; unemployed (people without work who have been actively seeking work within the last four weeks and are available to start work within the next two weeks); and inactive. There are six possible transitions between these three states: employment to unemployment, employment to inactive, and so on. My chart plots four of these flows, since current data began in 2001. These are taken from table X02 here.

This picture is messy. Which is big fact in itself. Labour market flows are high and volatile. On average in this time, 913,000 people have moved out of employment each quarter, and 970,000 have moved in. I'd highlight three points here:

1. Recently, flows from unemployment to employment have been very high. Before the crisis, most people entering employment did so from inactivity, not unemployment. Recently, though, the opposite has been the case. This has tended to depress measured unemployment lately.

2.Since the mid-00s, employment to inactive flows have fallen relative to flows from employment to unemployment. This has tended to raise unemployment, relative to the pattern we'd expect to see on the basis of pre-crisis flows. Before the crisis, most people leaving employment became inactive - say because they retired or became home-makers. This is still the case, but to a lesser extent.

3.Recently, flows from inactivity to unemployment have exceeded flows from unemployment to inactivity by an unusually wide margin. The net inflow to unemployment on this basis was 133,000 in Q3, compared to an average of 86,000 between 2001 and 2008.This makes the unemployment numbers look worse.

I don't say any of this to draw a big conclusion about whether unemployment will or won't fall quickly. My point is merely that unemployment can and does change for reasons other than changing employment levels. This is especially true when the economy is growing normally. Between 2001 and 2007, the correlation between changes in unemployment and changes in employment was only minus 0.43. For this reason, the headline unemployment numbers aren't always as informative as you might think.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers