Chris Dillow's Blog, page 134

December 31, 2013

Respect

Popbitch says that when Jay Z enters a room in his flat, workers are expected to walk to the nearest corner and face the wall until he leaves. Norman Lebrecht reports that customs officials at JFK airport destroyed a flautist's collection of flutes. Corey Robin notes that the University of Chicago bans workers from the lifts of its administration building. And Chris Bertram has documented ways in which American bosses tyrannize and humilate workers.

These examples give context to Noah's call for more equality of respect:

I want to move back toward a society where the hard work of an unskilled laborer is considered worthwhile in social interactions, regardless of how many dollars it brings home. I want to move back toward a society where being a good parent or a friendly neighbor earns as much respect as making a hundred million dollars on Wall Street.

In other words, I want our "democracy" back. We need to redistribute respect.

I agree. However, I fear that Noah is under-estimating the extent to which inequality of respect is endogenous. It arises out of the forces that generate and sustain inequalities of power and wealth. I'm thinking of inter-related mechanisms here:

- One way in which CEOs justify their power is by claiming the status of heroes, of brave, risk-taking leaders rather than rent-seeking apparatchiks. They therefore claim (and get) excessive respect.

- The successful underestimate the extent to which they owe their wealth to luck rather than skill, which leads them to demand more respect than is their due, and to disrespect others. Jay Z's attitude might be different if he recognized that there are many rappers like him, and he just got lucky.

- The just world effect means we want to believe that inequalities are fair.One way we do this is by believing that the poor deserve their fate because of their moral failings and so deserve to be disrespected.

- One big way in which capitalists have raised their profits and power is by deskilling. Jobs are increasingly routinized and monitored so that workers no longer have the autonomy or craft skills which were traditionally sources of (self-) respect.

- There's a totalitarian element to managerialism and neoliberalism. In elevating the pursuit of what Alasdair MacIntyre calls the goods of effectiveness (wealth and power) over those of excellence (skill at particular practices), they invite us to disrespect those who do pursue the latter goods - the competent workman or good neighbour.

To the extent that these mechanisms exist, I fear Noah is being a little naive. We cannot redistribute respect unless we remove sources of material inequality.

December 30, 2013

Lucky Osborne

Whilst I was away, the Times named George Osborne as its Briton of the year because he's "set the terms of political debate." This corroborates my prior belief that political reputations depend heavily upon luck.

To see what I mean, imagine that we hadn't seen productivity stagnate in recent years and that instead GDP per worker since the 2010 election had grown at the same 2.1% annual rate that it had grown by in the previous 30 years.

In this scenario, if output had grown by the same rate that it actually has since 2010, there would now be 1.85 million fewer people in work than there actually are, and employment would be 869,000 lower than it was when Osborne became Chancellor. If half those 1.85m were measured as unemployed, there'd now be 3.3 million unemployed - a record level.

This alternative world wouldn't be all bad: it would be one in which productivity growth had raised real wages and so there'd be no cost of living crisis. Nevertheless, it would be catastrophic for Osborne (though given the psychological cost of joblessness, this would be the least of our concerns.) His prediction that the private sector would create enough jobs to offset public sector cuts would be proved false, and the anti-austerians predictions of three million-plus unemployed would be correct.There'd be no "partial vindication" of Osborne. He'd be obviously wrong.

However, the fact that he has escaped this fate is pure luck. The causes of the productivity stagnation are obscure, but nobody believes Osborne's conscious policy decisions loom large among them. Neither Osborne's supporters nor detractors think he is responsible for flatlining productivity. And they are right.

In this sense, insofar as Osborne still has any sort of political reputation, it is thanks to the good luck of stagnant productivity.

In saying this, I don't mean that Osborne is uniquely blessed. I suspect that Thatcher's high reputation on the right is due in part to luck. And for years New Labour had the good fortune of a mostly benign global economic environment. Instead, my point is merely that in politics - as in life generally - luck plays an enormous role. Curiously, the rich and powerful, and their lackeys in the press, underplay this fact.

December 19, 2013

Profits & investment

Tim interprets Thomas Piketty's theory (pdf) that wealth concentration is rising because returns on capital are high as evidence against Marxism, as this predicts a tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

I fear he's being a little hasty here.

For one thing, Marx only saw a tendency for profits to fall, and cited numerous "counteracting factors" which could reverse this tendency. And for another, his idea of a falling profit rate was really just a rehash of the idea of the "stationary state" which pretty much all the classical economists had - that a time would come when diminishing returns overcame technical progress and caused growth to cease.

Let's though ignore that. There's a question here: if returns on capital are so high, how come companies are buying back shares rather than investing, and that so many are talking about secular stagnation?

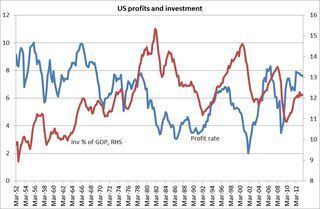

My chart highlights the issue. I've measured the US profit rate as non-financial pre-tax profits expressed as a percentage of the previous quarter's non-financial corporate assets, taken from the Fed's financial accounts. This shows that the profit rate trended down from the 50s to the early 80s, but has risen since, albeit punctuated by the tech crash and financial crisis*.

This is consistent with the trend in the income share of the top 1%, which also fell from the 50s to late 70s and has risen since**.

However, the turnaround in profit rates hasn't been accompanied by a rise in capital spending. The share of non-residential investment in GDP is lower now than it was in most of the late 70s and early 80s, when profit rates were lower. Higher profits, then, aren't providing much motive to invest.

One solution to this puzzle is that there's a discontinuity between past investments and future ones, or - if you prefer - between existing assets and growth options. Whereas past investments have been profitable, future ones are not expected to be so. The cliche's true - past returns really are no guide to future ones.

This is possible because investments are inherently lumpy and heterogenous. The fact that investments in iPads or Coca-Cola bottling plants has been profitable tells us nothing about the likely profitability of new future ventures.

This explanation strikes me as wholly reasonable. But it poses a serious problem for conventional neoclassical thinking. It means capital can't be aggregated and that the idea of a smooth, easily differentiable marginal product of capital is hooey - as some Cambridge economists pointed out (for different reasons) years ago***.

And this is why I say Tim is being hasty. If returns on capital are high, it's a problem not just for Marxism, but for neoclassical economics too.

* I'm using US data as there's more comparable longer-term data than there is for the UK. I suspect the trends in the latter would be pretty similar.

** Exactly what the link is is another matter. It could be that better management has raised profit rates and shareholders have rewarded top bosses for doing so. Or it could be that socio-economic change has raised profit rates and bosses have seized the proceeds of this for themselves. I shall leave the reader to guess which explanation I favour.

*** I know - if capital can't be aggregated the notion of an aggregate profit rate, as shown in my chart, becomes, ahem, problematic. I don't think this undermines my general point.

December 15, 2013

Ownership in question

Frances Coppola's account of Lloyds' high-powered incentives to staff for mis-selling products raises two general issues. To see them, read her description alongside allegations that RBS forced some of its business borrowers to close in order to acquire cheap assets.

Both these episodes are evidence against the Friedmanite hypothesis that businesses act in the public interest by maximizing profits. Better still, they show two of the circumstances in which Friedman's theory goes wrong.

One is if firms have significant market power. Had RBS's customers had alternative sources of finance, they could simply have borrowed from others, thus escaping RBS's clutches.

Another is when there's asymmetric information; Lloyds would not have been able to mis-sell products if customers had been well-informed about their shortcomings.

It would be a stretch - the commission of the journalist's fallacy! - to claim that these examples show that Friedman was entirely wrong. Instead, they suggest that he is right only in circumstances where corporate power is constrained.

The second issue is that these latest examples of banks' malpractice occurred whilst they were in public ownership. Which raises a paradox. When banks were privately owned, they mis-served the public interest by making huge losses and triggering a financial crisis, but when they were nationalized, they mis-served the public by being too zealous in the pursuit of profit. This is the exact opposite of the conventional wisdom, which says that privately-owned businesses maximize profits, whilst nationalized ones often have other objectives.

There's a simple reason for half this paradox. The banks were nationalized with the intention of restoring them to profitability quickly; in this sense, RBS and Lloyds were doing just what the government wanted. The government's attitude to banks has been that of a leveraged buy-out fund, using debt to invest in distressed firms with the intention of returning them to the stock market at a profit.

Nevetheless, this poses a more general question: what function does ownership serve? The financial crisis showed us that private ownership failed to prevent inept CEOs from making big losses. But Lloyds and RBS's behaviour shows that public ownership is not sufficient to make businesses act in the public interest either. This suggests that - for some businesses at least, neither form of ownership is, in itself, adequate.

However, the question of which forms of ownership are best for which businesses seems to be one which is, to a large extent, off the political agenda - which is yet another example of how mainstream political debate is narrower than it should be.

December 12, 2013

Universities as bullies

Nicola Dandridge's attempt to defend (2'14" in) gender segregation at some universities' debates has met with rightful derision on Twitter. Nobody, though, seems to appreciate just how disgusting it is.

Let's first dispose of her claim that gender segregation is "not alien to our culture". This is true but irrelevant. There is, as Stephen says, good and bad gender segregation. There's scientific evidence that single-sex schools can encourage girls to become more competitive and to pursue traditionally masculine disciplines - because in mixed schools, girls are primed to conform to sexist stereotypes. This form of gender segregation can promote gender equality by enhancing girls' life-chances.

There is, however, no such scientific, egalitarian motive for segregating the audience at debates. Doing so is just kowtowing to bigotry.This distinction is massive, and obvious.

This, though, raises a puzzle. Sure, some bigots want gender segregation at universities. But people make all sorts of requests of universities; they want them to pay their employees more; they want to stop privatizing their services; they don't want them to co-operate with gun-runners; and they want to enjoy what Ms Dandridge and I got - an education without a mountain of debt. But when students make these requests - in the lively way in which intelligent youngsters do - the response from universities is violence, suspensions and legal suppression.

This poses the question: why do universities meet unreasonable requests with supine acquiesence, and reasonable ones with force?

The answer Ms Dandridge would like us to believe is that the denial of a religiously-motivated request is a breach of human rights. This is self-serving crap. If a teenager sincerely believed that tuition fees were a blasphemy against his sky-fairy, would Ms Dandridge let him enter university for nothing?

Calling a dickhead idea "religious" does not give it legitimacy. And universities - which should be dedicated to rational inquiry - should not be privileging some unscientific ideas over others.

There is, though, two other differences between the demands of the religious bigot and those of the legitimate protestor. One is that the latter threatens the power and wealth of universty bosses, whilst the former threatens only the status of female students. Guess which one university bosses care most about?

The other is that the bigots' demands are backed with the (slight?) threat of real violence whilst protestors, lively as they are, don't threaten real harm.

In this sense, we should be grateful to Ms Dandridge. When universities cave into the threat of violence whilst using violence against the weak, they remind us that our managerialist rulers are basically bullies. And bullies respect not reason, but force.

December 11, 2013

Gift vouchers, & mispredicting markets

December 10, 2013

The income squeeze

December 9, 2013

Growth, levels & frames

December 8, 2013

"Attracting better candidates"

December 7, 2013

Tories, Apartheid & rationality

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers