Chris Dillow's Blog, page 126

April 16, 2014

The dark side of wage growth

Real wages are probably rising. The ONS estimates that nominal wages rose 1.9% in the year to February - though there's a big sampling error - whilst CPI inflation then was 1.7%. This, though, might have a downside.

I say this because a plausible reason for the growth in real wages is that productivity has finally begun to rise; total hours worked rose 0.4% in the three months ending February, but the NIESR estimates that GDP grew 0.9% then, implying productivity growth of 0.5%.

However, for a given rate of GDP growth, higher productivity growth means lower jobs growth.

What we might be seeing, therefore, is a shift in the way workers are benefiting from recovery. Until recently, we've seen employment grow rapidly but real wages fall. If real wages rise, this balance might shift.

In 2010-13, it was often said that one contributor to falling unemployment and weak productivity was that workers were pricing themselves into work by taking pay cuts. If real wages rise, this process would go into reverse.

This would be perfectly normal. The last two recoveries saw employment fall but real wages rise.

For example, in the 80s recovery, GDP troughed in 1981Q1 but employment continued to fall until 1983Q2, and did not return to its 1981Q1 level until 1986. In the 90s recession, GDP bottomed out in 1991Q2, but employment didn't trough until 1993Q1 and didn't return to its 1991Q2 level until 1997. In both periods real wages rose.

This tendency for recoveries to raise real wages rather than employment might reflect "insider" power; workers have power to push for wage rises, to the detriment of job creation. Or it might reflect rent-sharing; employers who enjoy rising productivity don't need to hire extra workers but do share the benefits of higher productivity with existing employees. Or it might reflect a mismatch between the skills successful firms need and those the unemployed have - so that firms prefer to work existing staff harder and pay them more rather than take on less-suitable new staff.

Whatever the reason, it could be that, if we do see genuinely higher wages, it might be because we're shifting to a more normal type of recovery - a jobless(ish) one.

Let's do some simple maths. To reduce unemployment from its current 2.24m to one million over the next five years would require the creation of something like 2.7m jobs; this is because of population growth plus the fact that many jobs are filled not by the unemployed by the economically inactive. To create this many jobs with 2% per year productivity growth requires real GDP growth of 3.7% a year for the next five years. That's more than a percentage point a year more than the OBR expects.

Mass unemployment, then, might be here to stay.

Another thing: You might object that higher real wages will create "wage-led growth" which will create jobs. I'm not sure. For one thing, they'll leak into higher tax payments. And for another, it's possible (contra the OBR) workers will use the gains to pay down debt. What we do know is that the early phases of the 80s and 90s recoveries did not see employment rise in this way.

April 15, 2014

What Phillips curve?

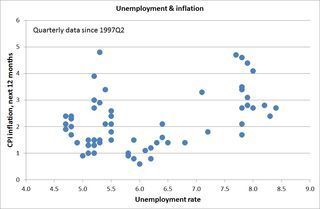

Today's news that CPI inflation has fallen to its lowest rate since October 2009 poses the question: what is the relationship between unemployment and inflation?

The fact that the fall comes after months of falling joblessness is awkward for conventional Phillips curve-type thinking, which says that lower unemployment should lead to higher inflation.

In truth, the latest episode is not unusual in this regard. My chart plots unemployment against CPI inflation in the following 12 months since the Bank of England was given independence in May 1997. It's clear that there's no neat single Phillips curve. In fact, taking all the data together gives us a positive correlation between unemployment and subsequent inflation; it is higher unemployment that leads to higher inflation, not lower.

I suppose you could espy a Nairu at around 5.3% and another at around 7.8%. But this doesn't help us with the current inflation outlook, as it merely poses the question: does falling unemployment mean there's the risk of inflation picking up, or does it mean the Nairu is falling?

There are several possible reasons for this apparently perverse relationship, most of them mutually consistent. Maybe this shows that inflation expectations matter; at a given unemployment rate, higher expected inflation will lead to higher actual inflation. Maybe it shows that shifts in the Nairu are of big practical significance. Maybe (relatedly) it tells us that supply shocks matter a lot; it could be that inflation and unemployment have both fallen because of a mix of lower commodity prices and a pick-up in productivity. Or maybe it means that the idea of an inflation-unemployment trade-off is dubious in an open economy:

In the closed economy there is a unique unemployment rate consistent with constant inflation. By contrast, in an open economy, there is a range of unemployment rates consistent with the absence of inflationary pressure. (Carlin and Soskice, p343)

Whatever the reason, the conclusion is the same. Statements such as "there is every chance inflation will pick up as economic slack is eroded" are more questionable than Phillips curve intuition suggests. Yes, inflation might rise. But you need to do much more than point to falling unemployment to believe it will.

This poses the question: why, then, are such statements so common?

One possibility is that we are unduly influenced by closed economy thinking in which there should be an unemployment-inflation trade-off. Because there's such a trade-off in the US - and because it's plausible that mass unemployment is causing low inflation in the euro area - we tend to think the same must be true in the UK. But it ain't necessarily so.

A more benign possibility is that such thinking is a way of smuggling demand management into monetary policy. The belief (or statement!) that a big output gap would reduce inflation allowed the Bank to slash rates in 2008-09. In truth, the claim "bugger inflation: let's try and save the economy" would have done just as well, but waffle about spare capacity allowed the Bank to appear to reconcile demand management with inflation targeting.

There is, though, a nastier possibility which Michal Kalecki famously pointed out - that the possibility of fuller employment makes many capitalists rather jumpy. But then, Kalecki can't possibly have been right, can he?

April 14, 2014

"Capital" and "labour"

Most people, says Arnold Kling, are "labor-capitalists":

Looking at the 21st-century economy through the filter of the Marxist categories of “capital” and “labor” is not particularly insightful. This is not a good era for either a plain coupon-clipper or an ordinary worker to accumulate great wealth.

You might imagine that, a a Marxist, I'd disagree. You'd be wrong. I agree with Arnold for a reason he doesn't mention.

This is that it has long been the case that wages, even for ordinary workers, contain an element of profits. Even before explicit profit-related pay became common, bigger, more profitable and more monopolistic firms tended to pay (pdf) higher wages. In one classic paper (pdf) Danny Blanchflower and colleagues concluded:

Pay depends upon an establishment's financial performance and oligopolistic position...Profitable employers therefore pay significantly more, ceteris paribus, than unprofitable ones.

What's true of workers is also true of bosses. A few years ago Frederick Guy wrote (pdf):

Virtually all studies of CEO pay levels find that most of the variation...is due to differences in firm size.

This explains something pointed out recently by Mike Perry - that the average US CEO earns less than an obstetrician. This is because the average CEO runs a small firms where profits are low.

Quite why CEO pay is so tightly related to firm size is an open question. At one extreme is the possibility (pdf) that in bigger firms the absolute value of CEOs' decisions is greater than it is in small firms; a CEO who can raise a company's value by 1% creates £100m in a £10bn company but only £1m in a £100m company. Big firms thus want to pay top dollar for the best "talent." At the other extreme is the possibility that larger firms generate more rents than smaller ones, which CEOs share in. Or, to put this a different way, CEOs have to be paid a fortune simply to pay them not to plunder the company's assets.

For the purposes of this post, we don't need a view on this issue. My point is instead that "capital" and "labour" don't necessarily map neatly into profits and wages, nor onto "workers" and "capitalists". Wages of workers and bosses can both be a share of the return on capital. In this sense, Arnold's right. There's a bit of capitalist in all of us.

This is, of course, not a new observation, nor one that is fatal to Marxism. I'm just reviving Erik Olin's Wright's idea of contradictory class locations. As he's written (pdf):

Managers within corporations, for example, can be viewed as exercising some of the powers of capital – hiring and firing workers, making decisions about new technologies and changes in the labor process, etc. – and in this respect occupy the capitalist location within the class relations of capitalism. On the other hand, in general they cannot sell a factory and convert the value of its assets into personal consumption, and they can be fired from their jobs if the owners are unhappy. In these respects they occupy the working class location within class relations.

This is true, to a greater or lesser extent, for millions of us.

This bears upon the debate about Piketty's book. All this implies that "r" - the return on wealth - directly affects earnings inequality. Which perhaps means Piketty's analysis matters for income inequality as well as wealth inequality.

April 12, 2014

Biased against stagnation

George Osborne tried yesterday to reject the idea that we've fallen into secular stagnation. I'm not convinced.

He points to some "new advances in fundamental science" and says:

We cannot even imagine the advances in all areas of science – from genetics to materials – that high powered computing will make possible in the years ahead.

This is plausible; to some extent, technical progress is inherently unpredictable. But it poses the question which Osborne didn't answer: are such advances monetizable? Capitalists don't invest because there's potential new technology. They do so because they expect to make profits. I fear that one under-rated reason for stagnation is that capitalists have wised up to William Nordhaus's famous finding - cofirmed by the experience of the tech crash in the early 00s - that "only a miniscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances" accrue to companies.

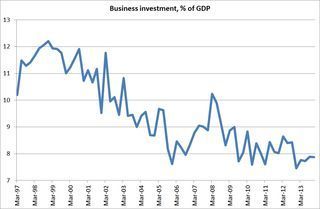

There one massive fact that Osborne ignored yesterday - that business investment has trended down as a share of GDP for years. Granted, this could be temporarily reversed if there's a surge in animal spirits - stagnation is wholly consistent with the emergence of bubbles - but Osborne gave us no new reason to think it could be more sustainably reversed.

This matters because it's plausible that Osborne's denial of stagnation rests upon some cognitive biases:

- Bayesian conservatism. Tories, and especially those who spent their formative years in the 80s, believe that the private sector is a powerful, vigorous engine of growth. This belief can persist even after the evidence for it has weakened. There are many examples of good ideas outliving their truth and usefulness. Maybe confidence in the private sector's ability to grow is one*.

- The optimism bias. Politicians of all parties are selected for their tendency to look on the bright side - to exaggerate their chances of success in a risky career, and to over-estimate their ability to improve human affairs. Maybe Osborne's just conforming to this pattern.

- The halo effect. The question of whether we've entered an era of stagnation is an empirical one; we either have or haven't, whatever else you believe. However, it is associated with calls for fiscal easing. Perhaps Osborne's hostility to the latter colours his attitude to stagnation. Strictly speaking, there's no logical reason for this: one could argue - albeit at a push - that we're in stagnation but that looser fiscal policy is no answer.

Now, I don't say all this to claim that we are definitely in stagnation. Maybe we're not. Biased beliefs are sometimes right, after all. My problem is that if Osborne's arguments against stagnation are so skimpy, there'll be a suspicion that they are informed by cognitive biases rather than clear thinking.

* We must distinguish here between the idea that free markets promote static efficiency and the idea that they create growth. You can believe the former without the latter: David Ricardo, for example, did so.

April 11, 2014

In praise of brevity

Last night, Laurie Penny tweeted: "Like many others I know, I'm trying to find a way of making it more viable to produce more of those longform, deeply-researched pieces."

Gawd help us. When will people realize that brevity and concision are virtues? I ask for several reasons:

1. Longform writing is narcissistic. It presumes that one's writing is so brilliant that it deserves to deprive readers of time they could spend doing other stuff - not least of which is reading other good things. And it is correlated with the notion that one's ideas are so complicated and nuanced that only thousands of words can do them justice; this ignores the fact that a few qualifiers - "mostly", "to some extent", "in this context" etc - can signal nuance.

2. Don't reinvent the wheel. Most stuff worth writing has been written already. Just link to it.

3. Anecdotes are not data. Stories add to the wordcount and give "colour", but they often beg the question: are these stories representative? Simply linking to data is more accurate, and briefer.

4. Assume your readers are intelligent. (Granted, this is a weaker assumption for me than it is for those condemned to write for the Guardian or Telegraph). They don't, or shouldn't, need everything explaining. They should also be able to see objections to what you write, and objections to those objections. And if they can't, ignore them.

5. There are diminishing returns to length. If readers think you're a prat after 500 words, they'll not change their mind after the next two thousand. In fact, there might be negative returns, simply because your gems are hidden. Laurie hides away a brilliant line - "Sometimes when you’re dying of thirst, you have to drink the Kool-Aid" - in thousands of words of ho-hummery. And none of the screeds written about Ed Miliband have affected my opinion of the man so much as a single paragraph from Steve Richards (again, hidden in unnecessary words).

It was Mark Twain, or maybe Blaise Pascal, who said "I didn't have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.” He was speaking an important fact about writing - that it consists in leaving stuff out. As Gabriel Garcia Marquez once said, writing should be like an iceberg - "supported below by seveneighths of its volume."

Regular readers might have spotted that I am rarely mistaken for Twain or Marquez, but I try to follow this; I have a rule on this blog to never write more than 600 words.

Of course, this rule cannot survive in the marketplace. Commissioning editors want long pieces in part because readers are apt to equate length with intelligence and seriousness. The MSM doesn't want links which direct readers away from their sites. And if we are paid by the word we'll produces thousands of bad ones rather than a few good ones. But perhaps this only shows that, as Niklas Luhman among others has pointed out, there is sometimes a tension between good communication and commerciality.

April 10, 2014

Efficiency wages for MPs?

In all the fuss about Maria Miller's resignation, a simple point has been ignored - that the issue here is a mainstream economic one. It's the principal-agent problem. How can principals (voters) ensure that their agents (MPs) behave in ways they want (keeping their hands out the till)?

Broadly speaking, there are three ways to achieve this.

One is simply to hire better people. However, given that most people would vote for a dead pig if it wore the right coloured rosette, this requires radical change.

A second possibility is to exercise greater direct oversight. In the Miller context, this requires simpler and tighter control of expenses. But as Ben Worthy says, we are a long way from this.

This leaves a third possibility - to give them greater incentives. One obvious possibility here is to use efficiency wages - that is, to pay MPs so much that the threat of losing their job will hurt more. This will incentivize them to be honest. As Mark Thompson tweeted: "The longer we will not countenance a pay rise for MPs the more gaming the system will tempt them." And from a different political perspective Jackart said: "The expenses scandal happened because we are too cheap and chippy to pay MPs properly, so we get the worthless fucks we deserve."

Now, efficiency wages are a big and important idea. One reason why the relative pay of low-skilled workers has fallen since the 80s is that managers have imposed direct oversight upon workers, thus reducing the need to pay an efficiency wage. And bankers and bosses are paid so much not because they are especially talented but because where direct oversight is impossible, they must be incentivized not to sell off the firms' assets cheaply.

So, should we pay MPs efficiency wages? I'm not sure. For one thing, efficiency wages are only an incentive if you lose your job when your caught fiddling; for this reason they might have to be combined with powers to recall MPs. And for another, there's a danger of incentive crowding out. If we pay MPs more, we might attract folk who are motivated only by money to the detriment of those motivated by public service; if you think MPs are only in it for themsleves now, it could be worse if they are better paid.

However, I doubt if these are the real reasons why the public would be opposed to Mark and Jackart's thinking. I suspect instead that the opposition to efficiency wages rests upon their counter-intuitiveness, in two ways:

- Efficiency wages break the link between productivity and pay. Their very point is that they entail paying people more than their marginal product. This conflicts with the intuition that people should be paid according to their skills.

- Efficiency wages are unjust. We are, in effect, bribing people to be honest - which is, in a sense, a reward for dishonesty.

My point here is a simple but depressing one. If we are serious in wanting to avoid another Miller "scandal", we need to think about how to apply agency theory to MPs. And this might entail some tricky trade-offs. Such thinking is, though, scarce. MPs want to pretend that they are basically honest people of good judgement, and voters are content with the occasional scandal because it gives them a chance to engage in bouts of narcissistic self-righteous moralizing. As for actuallly solving the problem, well, who cares?

April 9, 2014

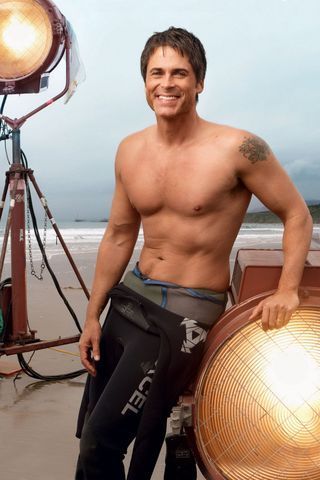

Rob Lowe & the left's dilemma

Rob Lowe, one of the stars of the greatest TV show ever made* has drawn our attention to a dilemma for leftist politics. He says: "There's this unbelievable bias and prejudice against quote-unquote good-looking people."

In one big sense this is plain false. There's abundant evidence around the world that there's discrimination in favour of good-looking people; they earn substantially more (pdf) than ugly ones. I doubt if Mr Lowe would have had so successful a career if he looked like Michael Gove**.

And yet on the other hand, there's a grain of truth in what he says. It's plausible that good-looking actors are overlooked for some interesting roles. And attractive people, I'm told, do suffer some inconveniences: being thought stupid (the "dumb blonde" myth); unwanted sexual advances; and being shunned by jealous rivals***.

Mr Lowe is focussing upon the partial costs of being handsome, and overlooking the fact that, overall, there are big net benefits to being so. This is quite natural: it's the grit in the shoe that gets noticed. And it's common; we see the same thing when some men complain about being victimized by feminism and when plutocrats whine about being persecuted. People who are advantaged overall can complain about their lot because they take for granted their many advantages but are irked by slight nuisances. It's this habit that is challenged by the phrase "check your privilege".****

However, if the privileged are apt to play up their complaints and play down their advantages, the poor can do the opposite. A combination of adapative preferences and ideology means they might resign themselves to their plight and so not complain sufficiently. As Amartya Sen has said:

Deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation because of the sheer necessity of survival, and they may, as a result, lack the courage to demand any radical change, and may even adjust their desires and expectations to what they unambitiously see as feasible (Development as Freedom, p62-63)

This brings me to the dilemma for the left. Most leftists today, for good and obvious historical reasons, are democrats. However, democracy - at least in the sense of heeding the voice of the people - can be anti-egalitarian insofar as it causes politicians to heed the noisy but minor complaints of the privileged whilst ignoring the bigger but silent plight of the genuinely worst-off. The tension between democracy and justice might be greater than leftists realize.

* Here's why.

** .

*** An attractive single friend of mine says other mothers are hostile to her at the school gates for fear she'll steal their husbands.

*** The phrase has a whiff of sanctimonious self-righteousness about it: note that it is "check your privilege", not "check my privilege".

April 8, 2014

Output gap, RIP

My immediate reaction to news that the ONS is going to raise its measure of GDP was: what does that do to estimates of the output gap?

In one sense, the answer is: nothing. The ONS is not so much revising GDP as redefining it; the main redefinition is that R&D now counts as part of GDP rather than as a cost of production. This means "potential GDP" is redefined precisely as much as "actual GDP", leaving the output gap unchanged.

But even so, this episode reminds me of my disquiet with the concept of the output gap.

One problem I have with it is that the estimates of potential GDP are parasitic upon our observations of actual GDP. For example, if the economy grows faster than we thought we might think "supply constraints are weaker than I'd thought so potential GDP is higher" or we might think "investment is rising and a higher capital stock raises potential GDP." Estimates of potential GDP tend therefore to be pro-cyclical.

This is dangerous - if policy-makers pay attention to the concept - because it might mean that monetary or fiscal policy become insufficiently counter-cyclical. In recessions, the fear that potential GDP has fallen could lead to low estimates of the output gap and hence a reluctance to ease policy: this might be because a low estimate of the output gap leads to higher forecasts of inflation, or because it leads to higher estimates of the "structural" budget deficit. Conversely, in booms, an over-estimate of productive potential leads to upwardly-biased estimates of the output gap and hence insufficient tightening.

My second problem is that the concept lacks microfoundations. Ideally, we'd measure the output gap by asking every company boss: by how much could you raise output without raising prices? But bosses might not know this. "Let's cross that bridge when we come to it" would be a reasonable answer. Their ability to expand production without incurring extra costs depends upon whether they can improve efficiency by learning perhaps very small and subtle improvements. But, by definition, we cannot know today what we'll learn tomorrow. This means the notion of "capacity" is an elastic and unknowable one. As this paper (pdf) concludes "capacity is not as well defined, even in batch-oriented manufacturing."

If people on the front line don't know what spare capacity they have, then economists trying to second-guess them won't know either. Unsurprisingly, then, estimates of the output gap vary hugely: from 6% (Capital Economics) to 0.8% (Fathom Consulting). This means that uncertainty about the output gap is huge. And if the noise-to-signal ratio about anything is high, we should discount that signal.

This is especially true because even if it were precisely known the output gap might not be much use to us.

One of its main purposes has been as an input into inflation forecasts; a big gap, ceteris paribus, predicts lower inflation. One big fact, though, tells us it's not necessarily a useful input. Inflation has fallen recently, even though the output gap is thought to have narrowed - from 4.4% in 2009Q2 to 1.7% in Q4 according to the OBR.

Of course, this might just tell us that things other than the output gap matter for inflation. But it might also corroborate what proper textbooks tell us - that in an open economy, there's a range of spare capacity consistent with any particular inflation rate.

The output gap, then, is ugly in theory and useless or worse in practice. As better economists than I have said, we should throw this daft idea into the rubbish bin.

April 7, 2014

Weird

At the gym yesterday, my eye was caught by the TV on the cross-trainer next to me flashing up a caption saying that 41% of voters think Ed Miliband is weird* (23'50" in). This is sinister, and not just because of the implicit tone of repressive narcissism.

There seems to be a presumption in the presenter's voice that weirdness is a bad thing. This is questionable. I'd like politicians to be geeks in the original sense of the word - people concerned about facts rather than what others think of them. And I'd like them to be disagreeable insofar as they resist pressure from lobbyists. Lance Price is right:

The constant media analysis of who we would rather have a pint with is not just patronising but stupid. None of the people I regularly have a pint with would be any good at running the country.

Historically, several very successful politicians have been "weirdos." Attlee was described as "the dullest man in English politics", Churchill was a manic depressive who worked in bed, and Gladstone spent his spare time studying (pdf) Homer's language of colour and trying to rescue prostitutes. How weird is that?

I suspect the assumption that weirdness is undesireable reflects a combination of pseudo-democracy and cargo cult managerialism. Voters want politicians to be like themselves, and presume that being "in touch" with ordinary people is somehow sufficient to promote their interests.

There's something else that's strange here. At the same time as Ed Miliband is called weird, a public school stockbroker who wants to destroy workers' rights is regarded as a man of the people, whilst an Eton-educated friend of a criminal who has twice been sacked for dishonesty passes for a likeable buffoon.

It's obvious that this odd mythology serves the interests of the ruling class. But why do some/many voters fall for it?

The answer, I suspect, lies in the notion of (rational) inattention. Most people pay very little attention to politics, which means their impressions of politicians are formed on the basis of a few biased cues: "Nigel Farage likes a pint - he's a regular bloke"; "Boris Johnson's got funny hair - he's a laugh"; "Ed Miliband looks strange - he's weird."

Now, I don't say this to defend Miliband. He's not "weird" enough for me, and John Rentoul is right to point to a perhaps grievous flaw in his character. I do so merely to point out that our current political culture contains some largely unexamined assumptions that are biased against even very modest challenges to the establishment.

* I try to make a habit of never watching current affairs programmes on TV.

April 6, 2014

On intersectionality

A row on Friday night between Anna Chen and Laurie Penny has reminded me to get round to writing a white male economists' perspective on the hot topic of intersectionality.

This, it seems to me, is a fancy word for an obvious idea - that people experience inequalities differently. The experience of black women - to take Kimberle Crenshaw's original example (pdf) - is different from that of white women; working class women suffer a different form of inequality than richer women; and so on.

This matters, because there can be trade-offs when we try to promote localized forms of equality. White feminists are sometimes accused of marginalizing black or trans women, for example, and demands for more women in boardrooms or the media leave class inequalities unchallenged. And so on.

I have four observations here:

1. Inequalities are not always additive. Some evidence on this comes from a paper (pdf) by Hilary Metcalf on wage inequalities*. She shows that, controlling for qualifications, black Caribbean and Indian women earn more that white ones. Yes, there's a gender pay gap and an ethnic pay gap, but they cut across each other. And there's also evidence that lesbians actually have a wage premium - although, paradoxically, they tend to have live in households (pdf) with lower earnings.

2. There's a curious omission in the inequalities which identity politics worry about - that between good-looking at ugly people. One UK study (pdf) - which is consistent with international evidence - found that boys who were considered unattractive by their teachers at the ages of 7 and 11 earned 14.9 per cent less than averagely attractive boys at the age of 33, even controlling for qualifications; ugly women suffered a 10.9% penalty. This pay gap is bigger than Metcalf's estimate of the adjusted pay gap between men and women or whites and blacks, and I suspect it's not offset by uglies getting a good deal in other spheres of life. The inequalities we hear about, then, are only a subset of those that actually exist.

3. The danger with identity politics is that it can degenerate into narcissism, or what Phil calls a "project of individual self-presentation." As Dr Crenshaw said (pdf): "the moment where a different barrier affects a subset of us, our solidarity often falls apart." I suspect this isn't wholly the fault of feminists, but is instead exacerbated by a form of projection: there's a tendency to presume that Laurie Penny or Caitlin Moran are "speaking for women" whereas nobody assumes that, say, Nick Cohen or James Delingpole are speaking for white men.

4. Although there's a tendency to regard the many inequalities as different, they have a common link - power. The powerful use their power to favour their group and disfavour out-groups. The fact that there's more ethnic diversity in the City than in the arts tells us that we'll not achieve equality merely by ensuring that the powerful have "liberal attitudes". This, though, poses the question: what would a society without power inequalities look like?

And herein lies a paradox. Perhaps the most widely studied blueprint we have for such a society is to be found not in leftist literature but in the economic textbooks. Under perfect competition, employers wouldn't have the power to discriminate. Of course, this alone wouldn't eliminate all inequalities, but it'd be a start.

* Of course, these are only a subset of inequality, but they give us a measure of how capitalism produces some systematic inequalities.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers