Chris Dillow's Blog, page 123

June 5, 2014

Politics in denial

In a welcome return to blogging, Giles Wilkes points out that there was no boom before the bust of 2008, so that morality tales of the recession being payback for living high on the hog are just silly.

He's right. But why was there no spending boom?

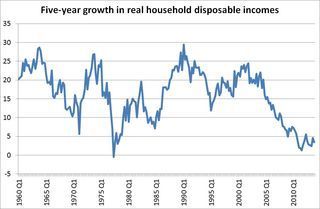

My chart shows one reason. It shows that growth in households' real incomes was slowing down long before the recession. For example in the five years to 2007Q4 - supposedly the boom years - it grew by an average of 2% per year. That compares to growth of 3.2% in the 40 years to 2002.

We don't have to look far for a cause of this slowdown. In the 00s, companies reduced their capital spending (relative to profits) and this depressed growth in incomes generally; investment is traditionally more a complement than substitute for labour, so investment growth usually means growth in workers' incomes.

This pattern is consistent with the "investment dearth" of which Ben Bernanke spoke in 2005; Robert Gordon's "end of growth" (pdf); Larry Summers' secular stagnation and Andrew Kliman's falling rate of profit.

It's this growth slowdown that led to the financial crisis. A lack of real investment opportunities meant that low interest rates fuelled what Austrians call malinvestments and Marxists "speculation and crises": mortgage derivatives grew in large part because there was a hunt for yield as bond yields declined. Stagnation generates bubbles, and bubbles burst.

This should be well-known to readers of this blog. Which poses the question Giles begins with: why do both Labour and Tories prefer to talk about the crisis as if it were a morality tale?

I suspect it's because they are in denial. Labour and the Tories agree upon one big thing - that capitalism is basically sound and needs only a few tweaks. But the fact that growth was faltering for deep structural reasons long before the crisis undermines this optimism.

What if capitalism can no longer generate decent increases in workers' incomes? What if conventional policies can do little about this? Such questions are off the political agenda. But they bring into question the very purpose of a politics in which the parties compete to offer higher living standards.

Perhaps, therefore, morality tales about the economy serve a useful function - they deflect attention away from the structural failures of capitalism and the inability of politicians to do anything about them.

June 4, 2014

Patriarchy as an emergent process

Ben Cobley criticizes the "ideological feminism" of Laurie Penny and others:

The idea there is a system perpetuating male privilege seems strange...This theory of patriarchy would be an almost perfect example of what Karl Popper called ‘pseudo-science’ if only its advocates claimed any sort of scientific backing. Instead feminists use the term as a free-standing fact that does not need serious evidential or logical support. The existence of patriarchy and the structures and systems which support it have to be taken on trust.

I'm not sure about this. I suspect that Laurie's ideas can be translated into scientific terms.

One thing we know about societies is that they are path-dependent; even quite distant history shapes behaviour decades later. For example, the extent of anti-Jewish pogroms in the 14th century predicted (pdf) the extent of Nazism; variations in the prevalence of US slavery are correlated (pdf) with variations in the black-white educational gap today; tax avoidance is widespread in Greece because it was seen as a patriotic duty under Ottoman rule. And so on. It is therefore surely plausible that today's societies contain at least some traces of their past sexism.

There are (at least) four inter-related mechanisms through which this might be so:

- The just world effect.People develop theories to justify inequality. It could be, therefore, that ideas of differences between men and women developed in response to inequalities between them, as an attempt to rationalize those inequalities. Such ideas mean that misogyny is tolerated.

- Stereotype threat and the Pygmalion effect. The Stanford prison and Oak School experiments show that people tend to live up (or down) to labels that are assigned to them even randomly; for example, children who are randomly labeled intelligent go on to do better on IQ tests than those not so labeled, and "guards" quickly become dominant whilst "prisoners" become submissive. Isn't it likely that a similar thing happens to genders - that (some) men conform to masculine stereotypes of ambition, dominance and violence and (some) women to stereotypes of docility? Empirical research shows they do. Laboratory experiments have found that women can be primed to do badly on "masculine" tasks, and research shows that when women are partially freed from their stereotype by attending all-girl schools, they choose more "masculine" subjects and become more competitive.

- Minority behaviour matters. Violent behaviour by some men can drive many women out of the public sphere. And this process can be self-perpetuating because...

- Role models matter. If we see people like us doing something, we'll be inclined to do it ourselves. The mere fact that many professions are dominated by men can therefore cause them to remain so dominated, because younger men are attracted into them and women deterred. As Akerlof and Kranton say:

In every social context, people have a notion of who they are, which is associated with beliefs about howe they and others are supposed to behave. These notions...play important roles in how economies work. (Identity Economics, p4)

What I'm saying here is that "patriarchy" might be a shorthand term for the fact that gender inequalities, like much else in the social sciences, are an emergent process. They arise not because of a conscious conspiracy, but as the unintended result of mechanisms. Perhaps, then, the concept of patriarchy is more scientific than the "not all men" trope.

June 3, 2014

House prices & class struggle

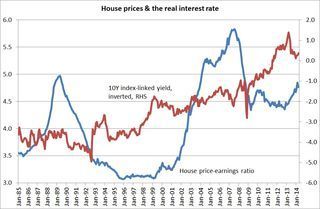

Simon Wren Lewis says high house prices might "reflect a view that real interest rates may stay low for some time". This is because house prices are equal to the discounted present value of future housing services, and a lower interest rate naturally raises that present value.

My chart shows a simple test of this. It plots the house price-earnings ratio against the 10 year index-linked gilt yield; the latter should be a measure of expected real interest rates. There is a correlation here, of -0.47 since 1985. Whether this is strong or weak is arguable*.

But there are good reasons why the correlation should be weakish, even if Simon's right.

One is that house prices are prone to bubbles and busts which might be unrelated to real rates; experimental research shows that asset prices are prone to bubbles and over-reaction.

A second is that the impact of real rates might interact with credit constraints, as John Muellbauer suggests.

A third reason is that the link between expected real rates and house prices depends upon what causes real rates to fall. If they fall exogenously - say because of a shortage of safe assets or global savings glut - then Simon's mechanism applies. But if they fall because of an increase in risk aversion or lower expected future incomes, it might not. This is because expected future housing services would decline along with the discount rate.

This set me wondering: is there a simple way to control for changes in risk aversion or expected incomes to get a cleaner estimate of the interest rate effect?

My first thought was: yes - use equity valuations. The idea here is that if real rates fall because of greater economic pessimism then we'd expect house prices to fall and dividend yields to rise. This should give us a strong negative correlation between real rates and house prices, conditional on the dividend yield, and also a negative correlation between the dividend yield and house prices.

So, I regressed the house price-earnings ratio onto the index-linked yield and All-share dividend yield since 1985. This gives us:

HPE = 3.9 - (0.33 x ILGY) + (0.28 x dividend yield)**

The coefficient on the index-linked yield corroborates Simon. It implies that a four-point fall in the index-linked yield raises the house-price-earnings ratio by around 1.3 notches.

But the coefficient on the dividend yield is the wrong sign! Higher dividend yields - stock market pessimism - are associated with higher house prices***. What could explain this?

Class struggle, that's what. Think of share prices as a claim on future profits and house prices as a claim on future wages; we buy housing services out of wages. We'd then expect to see share and house prices move in opposite directions if expectations about income shares vary more than expectations about future aggregate incomes. Lettau and Ludvigson (pdf) and Danthine and Donaldson (pdf) show that this can be the case.

I'd draw two lessons here:

- When you do any empirical work, you often find surprising results, and these can be easily rationalized.

- If my inference is right, and if you believe the profit share will rise in coming years for Piketty or McAfee/Brynjolfsson reasons, then we have another threat to house prices - distribution risk.

* I'm not sure the standard warning about spurious correlations in trended variables applies here, as Simon's claim is that the downward trend in long-term interest rates has caused an upward trend in house prices.

** R-squared = 28%, everything's statistically significant.

*** This remains true even if we control for policy uncertainty, as measured by the Baker-Bloom-Davis index.

June 2, 2014

"Understandable concerns"

What should be the relationship between politicians and the public? This is the fundamental question at the heart of Labour's response to concerns about immigration.

There have been, traditionally, two possible answers here. At one end, we have Edmund Burke's view that parliament is a "deliberative assembly" which ought not to heed "hasty opinion." On the other end is the "politics as consumerism" view, in which the customer/voter is king and should be given what he wants.

It's pretty clear to me that a party which took the Burkean view would tell voters that they are mostly wrong to link immigration and wages. Hopi seems to take this view in urging Labour to "have the courage of our convictions, even if it means a fight."

But I'm not sure the party is heeding him. Both Ed Miliband and Chuka Umunna have said immigration concerns are "understandable" - and they did so not merely in the context of unease about social cohesion but in the context of wages. And Yvette Cooper also links immigration and wages, without pointing out that insofar as there is a problem here at all the solution is a more redistributive tax and benefit system. Her demand to make serious exploitation a crime looks like a cack-handed version of the "left-right-left pivot" Hopi complains about.

In failing to tell the truth - that immigration has only mildly adverse effects on low-wage workers and that these face many more and greater threats to their livelihoods - Umunna and Cooper are following Gordon Brown. The worst aspect his notorious encounter with Gillian Duffy is not that he called her a bigot, but that he utterly failed to make the case for immigration.

What's going on here is a slide from the Burkean to the consumerist conception of politics; voters' concerns are "understandable" and must be listened to, even if they are mistaken.

Herein, though, lie two paradoxes. One is that some of the most successful businessmen - from Henry Ford with with (apocryphal) quote about faster horses to Steve Jobs saying "A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them" - haven't listened to customers. The other is that the more politicians talk about listening and connecting to voters, the less support and respect they've gotten.

The two paradoxes might be related by John Kay's obliquity. Sometimes, you can get want you want by not aiming directly for it. Ford and Jobs didn't waste time on market research but instead created great products.

Perhaps, then, Labour's urge to listen to voters is a two-fold importation into politics of the worst forms of corporate ideology. Not only does it see voters as customers, but it believes the party's objectives can be achieved merely by focusing on what voters seem to want, rather than by developing a worthy product.

June 1, 2014

Economists' advice

Whom should economists advise? I ask because of something Tim Harford says. He points to the abundant evidence that economists can't foresee recessions, and invokes Keynes' claim that economists should aspire to be like dentists:

We don’t expect a dentist to be able to forecast the pattern of tooth decay. We expect that she will offer good practical advice on dental health and intervene to fix problems when they occur. We should demand much the same from economists: proven advice about how to keep the economy working well and solutions when the economy malfunctions. And economists should bear in mind that no self-respecting dentist would be caught dead forecasting when your teeth will fall out.

To this, Unlearning Economics replies:

People expect dentists to tell them how to *avoid* tooth decay, not just deal with it if it occurs

Both seem to be assuming something which I find questionable - that economists should advise governments.

But why? Even if we knew for sure ways to keep the economy working well or to avoid recessions, there's no reason to suppose governments would follow such advice. If it fell outside the narrow Overton window, or if it clashed with the interests of the 1%, they might well ignore it. Shiller's proposals for macro markets to insure against big risks, and proposals to seriously fix the banking system, for example, have both been ignored. And economists' good ideas for improving well-being - on policies from fiscal policy through immigration to housebuilding - are also routinely ignored.

Dentists do not confine themselves to advising governments on dental health policy - even though they'd probably have more influence than economists - but instead help individuals.

Economists should do likewise. Here, we have a lot to offer. We know enough to give reasonable advice which can at least prevent savers from making terrible errors; this paper by John Cochrane is compulsory reading. For example, in the context of protecting ourselves from recessions, the following might help:

- Diversify: in many contexts, gilts are a hedge against recession-induced falls in share prices.

- Try and make yourself anti-fragile. If you have flexibility about when you retire, or if your human capital is portable, or if you can trade down your house, you have more ways of cushioning yourself against shocks. At least never put yourself in a position where you're a forced seller.

- When buying shares, use pound cost averaging; this limits our buying when prices are high, and raises it when prices are low. It also gives us an element of dynamic hedging - the ability to use low prices and high expected returns to offset falls in prices.

Dentistry is not much interested in politics - though dentists might reasonably lament inadequacies of dental health policy. I'm not sure economists should be much different, especially as giving policy advice causes people to under-estimate how useful economists can be.

May 30, 2014

Markets as ideology

One of Marx's big claims was that market transactions tend to disguise an exploitative relationship based on unequal power between capital and labour:

On leaving this sphere of simple circulation or of exchange of commodities, which furnishes the “Free-trader Vulgaris” with his views and ideas...we can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but — a hiding.

New research shows that Marx was right. Bjorn Bartling and colleagues set up a simple experiment in which a powerful dictator was endowed with artificial wealth which he could transfer to one of two weaker parties. The dictator was given a choice. He could either unilaterally transfer some wealth to one of the other parties, as in a simple dictator game, or he could use an auction in which the two other parties bid for it. After the transfer, the weaker parties were given the option to use some of their artificial wealth to destroy either the dictator's wealth or that of the other weak party.

They found that when the dictator chose competition, the weaker parties were significantly less likely to punish him even if the wealth he transferred was the same as when the dictator chose a unilateral transfer:

A powerful trading party, who could simply dictate the terms of trade, can deflect the blame for unequal outcomes by letting the market decide, i.e., by delegating the determination of the terms of trade to a competitive procedure.

All this is consistent with Marx. Market competition can reconcile people to inequalities which they would otherwise reject.

There's more. In competition, the weaker parties were more likely to punish each other. In this sense, the dictator's choice to use markets acts (unintentionally) as a "divide and rule" strategy. There is, I fear, a direct analogy here with unskilled white workers blaming immigrants rather than capitalists for their unemployment.

We have here, therefore, yet another example of how modern research proves Marx right.

Or do we? These results are also consistent with a McCloskeyan reading - that markets help promote peace and social stability, because they reduce people's inclination to spend resources predating upon others'.

In one sense, the McCloskeyan and Marxian interpretations are similar - both predict that markets reduce discontent.

May 29, 2014

Meritocracy, mobility & fairness

There's one point Greg Clark makes in The Son Also Rises which strikes me as plain wrong. It's this:

The world is a much fairer place than we intuit. Innate talent, not inherited privilege, is the main source of economic success (p14).

The problem here isn't merely that, as Rawls said, talent is arbitrary from a moral point of view and so should not be the basis for unequal incomes. (In fairness, Clark endorses this view). Instead, it's that a strong correlation between talent - innate or not - and economic success is no indicator of a just society.

Imagine a country run by a dictator, but one who is smart enough to see that it takes brains to run a centralized economy. He therefore selects apparatchiks according to rigorous tests of ability, and rewards them with wealth and power. Such a society will have a high correlation between talent and economic success. (It might also have a high correlation between soft skills and success, to the extent that success in a bureaucracy requires political and networking skills.)

Such societies are not purely imaginary. I'm thinking of Imperial China or the Soviet Union; it took intellect and skill to become commissar of tractor production.

However, I don't think Professor Clark would regard such societies as fair ones. And nor should he.

What's more, these societies would be unfair, whether the talented came from elite families or poor ones. In this sense, I agree with Matthew for a different reason; social mobility is no indicator whatsoever of a fair society.

Now, libertarians will object here that my argument is irrelevant to modern-day western societies because these are not centrally-planned dictatorships.

This, though, raises a paradox for libertarians who'd like to be meritocrats - though, as Hayek pointed out, you can't be both. It's that a just society for them is one in which people are free to give others whatever they choose. In such a society, though, we might well choose to reward people not because of their ability but for arbitrary whims. In this sense, the mark of a fair society is not that it rewards ability but that it does not do so. From a libertarian point of view, the evidence that our economies are fair is not that CEOs are paid millions - such people would probably succeed in centrally planned dictatorships too. It is instead that the likes of Kim Kardashian are well-paid.

May 28, 2014

The lust for order

Last night, I - along millions of other men - entered the mind of Elliott Rodger. Whilst watching Corrie, the question again arose: why is the world's most perfect woman married to a man with no redeeming qualities whatsoever? This echoes Rodger:

How could such an ugly animal have had sexual experiences with girls, and yet I haven’t? What was wrong with this world?

Such questions arise from an instinctive belief - which is a misreading of the Gale-Shapley algorithm - that the "best" men should get the "best" girls, that as Arthur Chu says:

what happens to nerdy guys who keep finding out that the princess they were promised is always in another castle? When they “do everything right,” they get good grades, they get a decent job, and that wife they were promised in the package deal doesn’t arrive?

The presumption here is wrong. This is not just because women are not prizes handed out on speech day, nor even because your reward for passing exams and getting a good job is merely to be chained to a desk for 80 hours a week. It's because love and lust are illogical and irrational. "What does she see in him?" (or him in her) are ancient questions. As if you need academic evidence, this paper (pdf) (via) concludes:

Human mating may depart substantially from a merit-based selection process. Romantically desirable traits actually appeared to be more relational than trait-like (i.e., consensual) across the contexts that we examined...Among individuals who knew each other especially well, the data revealed very little consensus and large amounts of unique, relationship variance. These findings reflect the natural subjectivity inherent in our perceptions of others.

Just look at David Beckham's or Christina Hendricks's choices of spouse.

Herein lies an aspect of Rodger's thinking that popular commentary has ignored - his inability to reconcile himself to the randomness that is love. As he wrote:

Life is not fair. One can either accept that fact, keeling over in defeat; or one can harness the strength to fight against it. My destiny was to fight against the unfairness of the world.

This is the mindset of the terrorist down the years - a desire to impose by force order and "justice" onto what are messy random processes. It is what Hayek complained of when he said that scientists and engineers are prone to "develop a passion for imposing on society the order which they are unable to detect by the means with which they are familiar" (p102 here). Diego Gambetta and Steffen Hertog show (pdf) that terrorists are disproportionately drawn from engineering backgrounds in part because they think that "if only people were rational, remedies would be simple." Sure, Rodger wasn't an engineer, but at least one previous misogynist mass-killer was.

Rodger fits the pattern of Nazis wanting a new order, Stalinists wanting a centrally-planned economy and Islamist terrorists.In all cases, we have the egomaniac's inabililty to see the beauty of unplanned disorder. And it is a beauty, because whilst it might hurt us to see a wonderful woman go off with a bell-end, one day that bell-end will be us.

I leave the last word to an infinitely greater authority than me.

May 27, 2014

The left & immigration

James Bloodworth writes:

The left must concern itself with formulating policy which offsets the impact of immigration on the wages of domestic blue collar workers.

That doesn’t mean pulling up the drawbridge on fortress Britain, but it does mean recognising that immigration impacts some more than it does others.

Here, we must distinguish between two separate issues: what to do about immigration? and: how to protect blue collar workers?

I say this for two reasons.

First, whilst there is some evidence that immigration has a small (pdf) impact on the jobs and wages of less skilled workers - many of whom are earlier cohorts of immigrants (pdf)- it's not obvious that an immigration ban would help them, even if such a thing were practical. Conventional economics - factor price equalization - tells us that if low-paid foreign workers are excluded from the UK, they will bid down UK wages via trade instead of migration.

Secondly, immigration is only one threat to the living standards of the worst off, and probably the lesser one. There's also: technical change; globalization (pdf); secular stagnation; mass unemployment and capitalist power embodied, for example, in power-biased technologies.

Singling out immigration from this list whilst neglecting the others is simply economically illiterate. I fear doing so is based upon a cognitive bias (the salience heuristic; immigrants happen to be especially visible) and the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy: "immigrants have arrived and now there's lots of unemployment."

In this sense, I agree with Owen. Regarding immigrants as a threat is an old "divide and rule" tactic which disguises both the fundamental weaknesses of capitalism and the fact that the main political parties - including Labour - have lost touch with the working class.

Luckily, there are some straightforward policies that would help cushion the low-paid not just against the largely mythical threat of immigration but also against genuine dangers. Policies to increase employment - including a serious jobs guarantee - would help, as would a more redistibutive tax and benefit system, including a citizens' basic income. One good point which Piketty makes is that redistribution can actually increase support for developments such as globalization and technical change by ensuring that their benefits flow to everyone, not just to the rich.

Of course, such policies don't address people's non-economic concerns about migration. But it's not obvious that people's human rights should be abridged to satisfy what are in some cases malign preferences.

Now, I don't know whether good economics makes for good politics in this case. I'd like to think so. After all, Quislings do sometimes end up getting shot.

May 26, 2014

Opportunity vs redistribution

Hopi Sen says the best response to immmigration is to give "our citizens the skills needed to succeed in a post-manual labour world":

I want a society where every child gets the chances of a Toynbee, or a Miliband, or a Cameron, or a Johnson, or a Dromey, or a Benn...I’m a social democrat. I believe in the ability of every citizen.

I'd love to agree with him, but some things make me sceptical.

First, there's a nasty possibility that many people lack the innate skills to succeed. This thought has been stressed by Greg Clark in (well discussed here and here). He points out that social mobility is very low even in modern-day Sweden. He says: "social status is inherited as strongly as any biological trait, such as height." Perhaps, therefore, there are powerful genetic or quasi-gentic reasons why there are so few latte-sipping elitists.

You might reply that the solution to this is to invest more in education. However, there's a big strand of thinking - associated with Eric Hanushek (pdf) - which says that such investments have very low returns. There's a reason why private schools charge huge fees - it's that education is a low-productivity job.

Even researchers who aren't as pessimistic as Hanushek find that big spending has only modest effect.For example, Steve Gibbons and Sandra McNally estimate (pdf) that:

A 30% increase in average expenditure per pupil improved test scores by about 8 points on our 1-100 scale.

It's touch and go whether this is cost-effective in raising future earnings. And I'm not sure whether governments committed to continued austerity would want to increase spending so much even if it did pay off 20 years later.

There's another reason why we'll never get a society in which everyone has the chances of a Miliband or Toynbee. It's that homophily is a powerful force. It was family connections that got Miliband an internship with Tony Benn, and which probably got the university dropout Toynbee her first journalism job. It's hard to see how such advantages can be eliminated.

And let's face it, people naturally want to hire folk in their own image.Sajid Javid's experience of discrimination by the British "elite" chimes with my own: when I was looking for jobs, offers came more readily from US investment banks who couldn't read my outsiderness than it did from British employers. But not everyone can work for Merrill Lynch.

I fear, then, that Hopi is guilty of that typical social democratic flaw, of excessive optimism about the human character.

There is, though, an another solution here - which could run alongside Hopi's efforts to prove me wrong. A more progressive tax and benefit system would help cushion the less skilled from the effects of immigration (and globalization and technical change), and thus ensure that potential Pareto improvements actually do benefit everyone.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers