Chris Dillow's Blog, page 103

March 19, 2015

On believing Osborne

What is George Osborne up to? This is the question posed by what the OBR's Robert Chote calls (pdf) a "roller-coaster" path for public spending. He foresees current departmental spending falling by 9% in nominal terms between 2014-15 and 2018-19 - a cut of over 15 per cent in real terms - but then jumping by 7% in 2019-20.

Simon and Atul say that this jump has a cynical political purpose: it's intended to kill off Labour's claim that the Tories plan to cut the share of spending in GDP back to 1930s levels. Simon says:

Maybe there has been a clear plan all along: to reduce the size of the state over a ten year period, using the deficit as cover.

I've never been convinced by this: why use a lousy argument about the deficit as cover for a more respectable one, the desireability of a small state?

Instead, might it be that Mr Osborne doesn't have a hidden agenda? That jump in spending is consistent with what he says he believes - that cutting spending will no longer be necessary by 2020 because the deficit will have been eliminated: he foresees a surplus on PSNB of £5.2bn in 2018-19.

I have four reasons for suggesting this:

1. If he's so keen to avoid that "back to the 30s" jibe, why did he give Labour the chance to use it back in December? Could it be that, back then, he didn't have the projected benefits of asset sales and lower debt interest costs and so felt the need to cut the deficit through spending cuts?

2. If he sincerely believes, as genuine small staters do, that governments can do more with less, why not say so and not bother projecting a big rise in spending in 2020? Could it be that he's forecasting it because he fears small government is unsustainable?

3. Much of his speech yesterday was not that of a small-state free marketeer. His talk of building a "northern powerhouse" and supporting "insurgent industries" had more in common with Harold Wilson's "white heat of technology" (pdf) than Friedrich Hayek.

4. He has not prepared the political ground for a permanently smaller state. For example, he's not especially encouraged economic research on the merits of small government, nor promoted studies of how (say) South Korea delivers decent public services at low cost, nor has he obviously encouraged those who want entire government departments shut down.

What I'm suggesting here is something radical. Maybe we should take Mr Osborne at face value. Perhaps there's less to him than meets the eye and he really does believe the guff about the necessity of austerity.

March 17, 2015

Media deference

Chris Bertram said yesterday:

When David Cameron announced that the Tories would reduce net migration to "the tens of thousands" it was obvious to anyone remotely well-informed that the policy was (a) bound to fail and (b) attempts to implement would result in illiberal nastiness on an unprecedented scale, divided families, stigmatization of minorities etc. Yet I don't recall broadcasters asking tough questions, treating him with derision etc. And this was a policy likely to be implemented by a party with a serious chance of power. Compare this with the snorting incredulity with which broadcasters treat, say, the Greens. It is almost as if those with a lower chance of power are held to higher standards of argument and evidence.

His point generalizes way beyond immigration policy. Whilst broadcasters seem obsessed with the non-existent "costs" of opposition policies such as housebuilding and cuts in tuition fees, they have grotesquely understated the costs of fiscal austerity.

The issue here isn't simply a partisan one. Mr Cameron has betrayed a confidence of the Queen; jeopardized the union: presided over a diminution of Britain's role in world affairs and kowtowed to the neo-racist far right. In all these respects he should have earned the contempt even of conservatives.

And yet this is not how he is portayed in the media.Why not?

The answer is only partly due to the economic illiteracy of mediamacro and bubblethink; these don't explain the easy ride Cameron has had in other policy areas.

Nor is it simply due to right-wing tribalism. For one thing, John Major was regularly portrayed as weak and incompetent - despite perhaps possessing more estimable personal qualities than Mr Cameron. And for another, leftists misdescribe Cameron. Even hostile cartoonists typically picture him as a heartless toff rather than a hapless sap who is out of his depth. And even even our most "leftist" newspaper can ask: "has Ed Miliband got what it takes to be Prime Minister?" without noting that the standard is now so low that any reasonable person could meet it.

Instead, I suspect that what we're seeing is simple deference, in two different senses. One is that Cameron's background, if not his conduct, means he is "officer class" material. He looks like a Prime Minister, even if he doesn't act like one.

The other is that, simply by virtue of having succeeded in acquiring power, Cameron attracts admiration. This is not just true for political reporters: just look at how football reporters have cringed supinely towards Alex Ferguson and Jose Mourinho. Adam Smith described the media - including the BBC - beautifully 255 years ago:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent.

March 15, 2015

The self-centred bias

The film critic Pauline Kael is reputed to have said after the 1972 election: "I donât know how Richard Nixon could have won. I donât know anybody who voted for him." The quote is apocryphal, but it captures a widespread error of judgement - our tendency to exaggerate the extent to which others agree with us. A new paper by Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi shows just how common this tendency is.

They show that students at the University of Warwick tend to over-estimate the numbers of fellow students: who are as happy or sad as themselves; who share their political orientation; and who own the same brand of mobile phone as themselves. More remarkably, they over-estimate the numbers who are of similar height or weight to themselves, even though height and weight are easily observed: fat people over-estimate the number of lardies and tall ones the number of beanpoles. They say:

Self-centred perceptions are ubiquitous, in the sense that an individualâs beliefs about the rest of the population depend on his or her own position in that distribution. Those at the extremes tend to perceive themselves as closer to the middle of the distribution than is the case.

This self-centred bias, which is related to the false consensus effect, might have numerous effects:

- It can contribute to an obesity epidemic. If fat people over-estimate what is a normal bodyweight, they are less likely to take the effort to lose weight.

- It can lead to bad investment decisions. If we exaggerate the extent to which others value an asset as much as us, we'll be more likely to pay a lot for it - leading to the winner's curse and to price bubbles.

- It can contribute to the middle England error - the tendency for politicians and journalists to over-estimate the numbers of people from posh backgrounds or with high incomes simply because they themselves are posh and rich. This can contribute to policies being biased towards the rich in the mistaken belief that they are "middle class."

- If we exaggerate the extent to which others share our beliefs, we'll tend to have excessive confidence in those beliefs. We'll think: "if so many of us think the same way, we must be right.

- We'll become less tolerant, because beliefs and behaviour which are different from ours will be seen as aberrant. This might have contributed to the closing of liberal minds of which Tim Lott complains.

- It can contribute to behaviour which is later regretted. I suspect the MPs expenses "scandal" occurred because MPs thought tweaking expenses was normal and so under-estimated how bad it would look in public. Similarly, HSBC bosses might have thought collusion with tax-dodging was tolerable simply because their fellow bankers thought so - and forgot that the public thought differently.

For me, one implication of this is that we should go out of our way to seek out cognitive diversity - to remind ourselves that our ideas might be minority ones. This is why the creation of "safe spaces" in universities is to be regretted.

However, this bias isn't always a costly one. Quite the opposite. The entrepreneur who thinks "I reckon this is a good idea, so others will too" is more likely to give us new products and companies than the man with a clearer-minded view.

Cognitive biases aren't always bad things - which, given their ubiquity, is just as well.

March 14, 2015

"We'll have to look at the data"

Here are some things I've seen this week:

- Describing the decline of universities, Marina Warner says: "not everything that is valuable can be measured."

- Some US newspapers have signed up to Blendle, allowing readers to pay to read individual articles.

- Dave Tickner says that Peter Moores' response to England's being knocked out of the World Cup - "We'll have to look at the data" - "sums up everything's that's wrong" with his management.

- South Yorkshire police diverted funds from sex abuse inquiries towards tackling car crime, which the Force was targeting.

- Mike Goodman says that much of Mesut Ozil's contribution to Arsenal doesn't show up in statistics.

These apparently disparate things all bear upon the same question: can information be fully quantified, codified and therefore centralized, or were Hayek and Polanyi right to claim that some knowledge is inherently fragmentary, tacit and dispersed?

This is of course not merely a matter of epistemology. It bears directly upon how organizations should be structured. If everything can be measured by a central authority then hierarchy is feasible. If not, then we might need more decentralized forms of organization. It's no accident that the increased use of metrics in universities has coincided with the rise of vice-chancellors' salaries. Claims about knowledge are also claims to power.

As with most questions in the social sciences, the answer here is: to some extent. Given the ubiquity of cognitive biases, data can tell us what really works; this is the message of Moneyball. For example, stats disprove the claim that Ozil is lazy. And targets and quantification can be used to identify lazy academics and policemen.

However, good ideas can be pushed too far, with counterproductive consequences: revenge effects are common. There are at least four different mechanisms through which this can happen:

- Gaming. David Boyle has claimed that school league tables led teacher to focusing excessively upon D-grade students at the expense of others, because converting D to C grades improved schools' performance. Similarly, South Yorkshire police were told to target car crime, they did just that to the detriment of tackling what we now know to have been more serious crime. This was an example of the drawback of centralized over dispersed knowledge; the belief that sex abuse was a serious problem was a hunch of a few junior officers, whereas knowledge of car crime was more quantified and centralized.

- Excessive investment in measured outcomes. This happens when academics are encouraged to write grant applications rather than teach students. And it'll happen if journalists are paid per click: we all know that the way to attract eyeballs is to write about celebs or shrill partisan pieces.

- Some stats are just bad and can give a mere illusion of knowledge. For example, in 2007-08 banks' risk models were based on data which over-sampled low volatility and under-sampled high. The upshot was that the crisis came as a shock. David Viniar, Goldmanâs chief financial officer, famously said: "We were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row.â But in fact, a better inference would have been that risk was mismeasured.

- Adaptive markets. Companies or sports teams might get a competitive advantage from using statistical methods but they cannot retain it, simply because others will emulate them. This too is a message of Moneyball.

Herein lies my problem. I fear managers are underestimating these drawbacks. This might be simply because of deformation professionnelle - the tendency for one's professional background to warp one's perspective. Or it might instead be an example of Upton Sinclair's famous saying: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

March 13, 2015

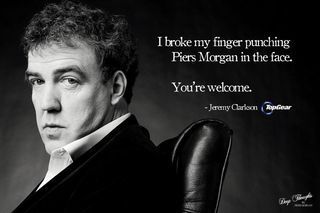

Jeremy Clarkson as central bank

In all that's been written about Jeremy Clarkson, nobody has pointed out that there's a close analogy between him and central banks.

Mr Clarkson's critics seem to believe that he should have followed the rule "don't punch people." They are wrong. If he'd obeyed this rule, he would not have twatted Piers Morgan. There would therefore have been a sub-optimal amount of twatting.

Equally, however, Mr Clarkson should not be free to hit whomsoever he wishes. This would create the danger that he would sometime hit the wrong person, and it would generate uncertainty among his acquaintances.

We have exactly the same problem with central banks. If these follow a rule* - such as "keep inflation at 2%" - there will sometimes be a suboptimal level of stimulus. For example, if commodity prices surge or if a financial crisis doesn't immediately reduce inflation, a strict inflation-targeting central bank would not loosen policy sufficiently.

Equally, though, giving the Bank full freedom to do what it wants would create uncertainty. In the classic Kydland & Prescott paper (pdf), this leads to unnecessarily high inflation.

What we have in both cases is a debate about rules versus discretion. Rules such as "don't punch people" or "target 2% inflation" can sometimes be suboptimal. But discretion also has costs.

One possible solution to this is what Ben Bernanke called "constrained discretion." This is what the Bank of England has. Its remit (pdf) says:

The actual inflation rate will on occasion depart from its target as a result of shocks and disturbances...Attempts to keep inflation at the inflation target in these circumstances may cause undesirable volatility in output due to the short-term trade-offs involved, and the Monetary Policy Committee may therefore wish to allow inflation to deviate from the target temporarily.

The hope is that this gives us the best of both worlds. The 2% target anchors expectations and so gives us certainty. But allowing the Bank to respond to shocks gives us more discretion to stimulate growth when necessary.

Again, there's an analogy with Clarkson. A better rule than "don't punch anyone" would be: "punch nobody but we'll allow some exceptions to this."

Herein, though, lies the problem. We cannot precisely specify what these exceptions might be. In the case of central banks, Daniel Thornton has explained why:

The economy is too complex to be summarized by a single rule. Economies are constantly changing in ways difficult to explain after the fact and nearly impossible to predict. Consequently, policymakers seem destined to rely on discretion rather than rules.

Much the same is true in Clarkson's case. We cannot say in advance whom he should be permitted to hit. Piers Morgan, Robbie Savage and Nigel Farage are obviously permissible targets, but there are many potential others some of which have yet to achieve public prominence.

In both cases, therefore, it seems that discretion is best.

But this too has a potentially heavy cost. As Adam Gurri says, people are "terrible" at using their judgment. Again, this is true both for central banks and Clarkson. The ECB seems to have delayed QE until the economy is recovering, just as Clarkson (allegedly) mistakenly punched an innocent man - or as innocent a one as a BBC producer can be.

I suspect one solution to this might be to have form of level targeting of the sort advocated by Scott Sumner:

If you target NGDP to grow at 5% a year, and it grows 4% one year, you shoot for 6% the next.

In effect, if (or rather when) you make an error once, you must aim for the offsetting error later. The analogy for Clarkson would be that, having hit an innocent man, he must err on the side of passivity in future. Sure, this would entail the significant cost of not hitting Piers Morgan again. Luckily, though, what's true for Clarkson should also be true for everyone, so there should be an optimal amount of twatting of Mr Morgan - by which, of course, I mean a very large amount.

* There is a useful distinction between target rules and instrument rules. I'm ignoring this.

March 12, 2015

On anti-discrimination laws

Nigel Farage wants to scrap a lot of discrimination laws. From one perspective, this isn't wholly outrageous.

In principle, there's a stronger barrier to discrimination than mere law - competition. As Kristian Niemietz says, channeling Gary Becker:

A competitive market economy provides us with strong incentives to keep our personal prejudices out of our business decisions. Even the most sexist/homophobic/racist employer can realise that by hiring only heterosexual men of Saxon descent, they limit the talent pool accessible to them, which is not smart business. Especially when talented applicants can go on and work for a competitor.

There's some truth in this. Competition explains why Ron Atkinson - a man later revealed to have racist attitudes - hired black players in the 1970s. And it explains why "politically incorrect" financial firms have more ethnic diversity than the "liberal" arts establishment.

I would rather racists who hire inferior Brits over talented foreigners go bankrupt and lose their life savings than merely get a slap on the wrist from law courts which feeds their martyr complex.

But. But. But. There's a question here which applies to many theories in the social sciences. Whilst Becker's theory that competition reduces discrimination is partly (pdf) true, just how true is it?

The wheels of competition just don't grind finely enough to entirely root out discrimination; the fact that there are ethnic (pdf) pay gaps (even controlling for qualifications) tells us this. And, I fear, this would remain the case even if measures were taken to increase competition; a perfectly competitive economy is a textbook ideal, and not something seen in the real world.

My doubts here are reinforced by an agency problem. Tesco's bosses (say) - and certainly their long-suffering shareholders - might well genuinely want to maximize profits and so hire the best people. But do the petty tyrants who run their stores really wholly share that aim? And wouldn't a few of them have sufficient wiggle room to indulge their own prejudices against the interests of their distant employers? There is a great deal of ruin in any large organization, and within that ruin there's room for discrimination to survive.

And to the extent that big local employers sometimes enjoy at least a modicum of monopsony power, I'm not sure it's good enough to claim that the victims of discrimination by the minority of racists would find equally rewarding work elsewhere.

Now, I am expressing all this in the form of doubts and scepticism for a reason. The question here is: on which side do we wish to err?

Let's say my doubts are ill-founded and discrimination laws are superfluous. Then nobody gains or loses from their removal - because firms would carry on hiring the best people anyway.

But what if my doubts have even a little validity? Then the winners from removing such laws are racists. And the losers are meritorious ethnic minorities. Do we really want to take the risk of helping the former and hurting the latter? And what does it say about Mr Farage that he is willing to do so?

March 10, 2015

Economists! Be more Marxist

I pointed out yesterday that Marx was right: inequality generates an ideology which defends that inequality. This, though, is just one of many instances in which experimental or empirical evidence has vindicated him.For example:

- The "economics of life" literature pioneered (pdf) by Gary Becker - as exemplified by Jeremy Greenwood's work on how technical change has changed sexual mores and family life - confirms Marx's claim that "The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life."

- Some experimental evidence vindicates Marx's claim that hierarchy doesn't simply increase efficiency, but also leads to exploitation.

- A lot of public choice work is consistent with Marx's claim that "the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie".

- Marx's claim that capitalism is prone to crises looks better than the simpler class of DSGE models which under-rated the chance of crisis.

- Work on cognitive biases inspired by Daniel Kahneman corroborates Marx's theory of ideology.

- The degradation of "middle class" jobs fits his claim that "The lower strata of the middle class sink gradually into the proletariat."

- The evidence that robots have not (yet?) depressed demand (pdf) for labour might be consistent with Marx's view that new machinery doesn't hurt labour but capital, because it causes older technologies to suffer "moral depreciation" as they can no longer compete against the newer, better equipment.

- Even the much-maligned labour theory of value fits a lot of facts.

In light of this long list, it shouldn't be surprising that Marxian economics helps shed light upon important contemporary issues. His theory of a declining profit rate - which happens to be true (pdf) - should be part of any theory of secular stagnation. Class struggle, power and exploitation are at least as reasonable ways of thinking about inequality as marginal product theory. Long-term moves in share prices are due in surprisingly large (pdf) part to class struggle. And Marx's work on technical change should feature in the debate about the impact of robots on work and society. (Hint: capital competes with other capital, not just labour.)

Of course, Marx wasn't right about everything - but nobody is. I'm not at all sure that capitalism has a tendency to ever-increasing monopoly. And his idea that the working class would become an agent of revolutionary change has been wrong. For these reasons, we should, in Yanis Varoufakis's lovely phrase, be "erratic Marxists".

When I say "we", I don't just mean we Marxists. I mean all economists. I suffer no dissonance at all between writing (more or less) conventional economics in my day job and being some kind of Marxist. The important distinction is not between heterodox and orthodox economics, but between

good and bad economics - and Marx is often good economics, in the sense of fitting the facts.

In fact, though, there's another reason why orthodox economists should be (partly) Marxist. It's that a class society militates against rational economic policy, in three ways:

- It increases popular support for immigration controls. In a class-divided society poorer workers see migrant workers and think (wrongly, but sincerely): "they're taking my job." In an egalitarian society, they'd be quicker to see that migrants free them to do more productive work.

- A big reason why we don't have a rational fiscal policy is that it runs against the interests of capital. As Kalecki said, big business would rather that employment depended upon their confidence. And we might add that finance capital would prefer a loose money/tight fiscal policy mix. Reducing capitalists' power might be an essential prerequisite for sensible fiscal policy.

- Capitalism quickly degenerates into crony capitalism or corporatism because capitalists buy political influence. If you want a properly freeish market economy, you should therefore favour institutional changes which reduce the power of the rich.

So, here's my message to all non-Marxist economists. You should take Marx more seriously. I mean, you're not just shills for the rich are you?

March 9, 2015

Tolerating inequality

Inequality sustains itself by generating an ideology which favours the rich. This might sound like classic Marxism - which it is. But it is also orthodox social science, as a new paper from the NBER shows (ungated pdf).

Jimmy Charitie, Raymond Fisman and Ilyana Kuziemko ran a simple experiment. They randomly gave $5 and $15 to two people and then asked others whether they wanted to redistribute the money between those two people. On average, subjects voted to close 94% of the $10 gap. However, when subjects were told that the two people already knew whether they were getting $5 or $15, they closed only 77% of the gap.

This suggests that preferences for redistribution depend upon reference points. In the first experiment, the reference point is an equal allocation. In the second, however, there's another possible reference point - people's expectations. Such expectations reduce demand for equality.

The effect here is big. The experimenters also allocated the $5 or $15 according to scores on a SAT and then asked people to redistribute. On average, they closed 56% of the difference. This tells us that the effect of tweaking reference points on people's tastes for equality is equal to about half the effect of the difference between random allocations and merit-based ones. I reckon this is quite a lot.

You might be thinking here of Scott Alexander's wise warning: beware the man of one study. Except this is not the only research on this point. Experiments by Kris-Stella Trump have found a similar thing. She says:

Public ideas of what constitutes fair income inequality are influenced by actual inequality: when inequality changes, opinions regarding what is acceptable change in the same direction.

The very fact that the share of the top 1% in UK incomes has more than doubled since the 1970s (from under 6% to 12.9%) might therefore reduce demand for redistribution.

Several cognitive biases feed into this: the status quo bias, anchoring effect and just world illusion.

The point here is surely important. Public tolerance of inequality can increase as inequality increases. This isn't (just) because of a biased media - the media doesn't exist in these experiments - but because actual inequalities condition our attitude to fair inequalities.As Marx said:

Men, developing their material production and their material intercourse, alter, along with this their real existence, their thinking and the products of their thinking.

Marx was right.

March 8, 2015

Does the current account deficit matter?

Will Hutton has, inadvertently, provided a case for fiscal austerity. He writes of our record external deficit and deficit on net investment income:

If these trends continue for another 10 or 15 years the interaction with our growing trading deficit – we import a great deal more than we export – will eventually make the scale of our international debts and income flows abroad insupportable. There will have to be a massive national belt-tightening along with the imposition of controls of capital to stop a runaway sell-off of what will be valueless pounds. The curtain will come down on an era of amazing economic fecklessness.

Before seeing why this claim might justify tighter fiscal policy, let's just strengthen Will's argument in three ways:

- The UK's net foreign liabilities are now equivalent to 25% of GDP - their largest since records began in the 70s. Whilst this is roughly the same as Australia's, the US's or France's, the only major countries with significantly bigger liabilities are either those that ran into a big financial crisis because of their overseas debts (Greece, Spain) or poor countries for whom high liabilities represent FDI from overseas to take advantage of their decent long-term growth prospects.  The UK is not in the latter category.

The UK is not in the latter category.

- A current account deficit, by definition, means domestic investment exceeds domestic savings. This can be a sign that bank lending is growing faster than deposits - which might be a warning of an impending financial crisis. Is it really an accident that the countries which suffered most in the Great Financial Crisis all had big and persistent deficits - Greece, Spain, Ireland, US and UK?

- We can't rely upon a fall in stering to eliminate the deficit: net exports just aren't very sensitive to exchange rate changes.

Herein, then, lies the case for austerity. A tighter fiscal policy would - in the absence of 100% crowding out - raise national savings and thus reduce the deficit. The bigger the fiscal multiplier, the more it does so - because there's a bigger drop in aggregate demand and hence imports. In this sense, fiscal austerity imposes hardship now in order to prevent a "massive national belt-tightening" in future.

I suspect Will does not want to reach this conclusion. And there's a good reason why he shouldn't. The UK's current account deficit is a symptom of the global savings glut and secular stagnation. By definition, the UK's deficit means that the rest of the world's domestic savings exceeds their investment. Foreigners are buying London houses and British businesses because they can't find sufficient productive investments at home.

One thing tells us this is a better way of regarding our deficit than the "amazing fecklessness" Will describes. It's that foreigners are happy to lend to us. Since early 2010 sterling's trade-weighted index has risen 15% and ten year gilt yields have fallen faster than US yields.Neither would have happened if the UK were in a desperate fire-sale of assets to fund profligacy.

Now, I don't say this to mean that the deficit is not a problem. Given the lack of global capital mobility, it is. As Sushil Wadhwani once said (pdf):

It is possible that the current account only matters some of the time. Casual observation suggests that countries with a current account deficit can have a currency that stays strong for a surprisingly long period, until, sometimes, there is an abrupt adjustment.

This might be an example of what Sornette and Cauwels call "creep": things can look robust until they suddenly collapse.

Instead, the question is: must we do something about the deficit now? I suspect perhaps not. Insofar as the deficit is partly the counterpart of high savings and weak demand in the euro area, we should wait until those problems are diminishing before trying to reduce it ourselves.

March 5, 2015

Wages as social constructs

This passage from Paul Krugman has stirred controversy:

Conservatives — with the backing, I have to admit, of many economists — normally argue that the market for labor is like the market for anything else. The law of supply and demand, they say, determines the level of wages..

But labor economists have long questioned this view. Soylent Green — I mean, the labor force — is people. And because workers are people, wages are not, in fact, like the price of butter, and how much workers are paid depends as much on social forces and political power as it does on simple supply and demand.

I fear, though, that both Krugman and David Henderson are making a false distinction here. It's possible to argue that wages depend upon social forces because those forces affect the position of supply and demand curves.

For example, a wage of, say, $8ph might not attract much labour supply in western economies but the same wage (in PPP) terms would have applicants queuing for miles in a poor country. The labour supply curve in the west is to the left of that in poorer nations. Why?

A big reason is that, in the west, such a wage is regarded as derisory because it would not give us an acceptable standard of living. This is because our ideas of what's acceptable are socially conditioned and so are greater in rich countries than poorer ones. As Smith said:

By necessaries I understand not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life, but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without. A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt.

Also, the position of demand curves depends upon social forces. Conservatives would agree that wages depend upon the value of the output created by a worker. But this value is subjective and our subjective valuations are conditioned by social forces. For example, at a wage of $10 million per year there is positive demand for chief executives but not for toilet cleaners. This is because hirers believe that CEOs can create at least $10m pa of value. I would argue that this belief is a contestable ideological one: it exists because boards believe not only that great men can transform company's fortunes but also that they have the ability to spot such men. Both beliefs are questionable. It takes no imagination to envisage a society in which CEOs are paid only moderately because managerialist ideology is weaker.

Here are some other examples:

- IMF research shows that inequality has increased as trades union power has declined, because unions were a constraint upon bosses pay.

- Wages are lower in feminized occupations, even for men - consistent with "women's work" having low perceived value. The fact that this is more true in the UK than Germany hints at a social and cultural basis for the difference.

- A classic paper (pdf) by Kahneman Knetch and Thaler showed that perceptions of fairness are a cause of wage stickiness. For example, people think it fair for a firm to cut wages if it is making a loss, but not if there's mass unemployment in the area.

- Power-biased technical change has contributed to wage inequality. Because low-skilled workers can now be monitored directly - through CCTV, containerization, electronic tills and suchlike - they no longer need to be paid efficiency wages to keep them honest. This means their relative pay has fallen.

All these cases show that Krugman is right to say that wages depend upon social forces and political power. However, this is not an alternative to standard price theory but a complement to it. Forces and power help explain how demand and supply curves are formed.

Now, you might think this agreement with Krugman leads me to sympathize with his call for higher minimum wages. Not necessarily. In a world in which customers and thus employers attach low value to cleaners and care home workers, a state-mandated rise in their pay (which as Bob Murphy says is a different thing from a voluntary pay rise) might well depress demand - especially in the absence of looser macroeconomic policy.

The problem here, though, isn't "natural" laws of economics, but a cultural and ideological climate which attaches low value to some types of work. If this climate were to change - and the demand curve for such labour were to shift outwards - higher wages for such workers would be entirely feasible.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers