Josh Clark's Blog, page 8

April 20, 2024

John Maeda: Josh Clark's 2019 talk on Design and AI

Design legend John Maeda found some old gold in this 2019 talk about Design and AI from Big Medium’s Josh Clark:

What���s especially awesome about Josh���s talk is thatit precedes the hullabaloo of the chatgpt revolution.This is a pretty awesome talk by Josh. He has been trailblazingmachine learning and design for quite a long time.

The talk, AI Is Your New Design Material, addresses use cases and applications for AI and machine learning, along with some of designing with (and around) the eccentricities of machine intelligence.

(Also be sure to check out John’s excellent SXSW Design in Tech Report, “Design Against AI,”.)

Josh Clark's 2019 talk on Design and AI | John MaedaUS Air Force Confirms First Successful AI Dogfight

Emma Roth reports for The Verge:

After carrying out dogfighting simulations using theAI pilot, DARPA put its work to the test by installingthe AI system inside its experimental X–62A aircraft.That allowed it to get the AI-controlled craft intothe air at the Edwards Air Force Base in California,where it says it carried out its first successful dogfighttest against a human in September 2023.

Human pilots were on board the X–62A with controlsto disable the AI system, but DARPA says the pilotsdidn���t need to use the safety switch ���at any point.���The X–62A went against an F–16��controlled solely bya human pilot, where both aircraft demonstrated ���high-aspectnose-to-nose engagements��� and got as close as 2,000feet at 1,200 miles per hour. DARPA doesn���t say whichaircraft won the dogfight, however.

What could possibly go wrong?

US Air Force Confirms First Successful AI Dogfight | The VergeLooking for AI Use Cases

Benedict Evans makes a savvy comparision between the current Generative AI moment and the early days of the PC. While the new technology is impressive, it’s not (yet) evident how it fits into the everyday lives or workflows of most people. Basically: what do we do with this thing? For many, ChatGPT and its cousins remain curiosities���fun toys to tinker with, but little more so far.

This wouldn���t matter much (���man says new tech isn���tfor him!���), except that that a lot of people in techlook at ChatGPT and LLMs and see a step change in generalisation,towards something that can be universal. A spreadsheetcan���t do word processing or graphic design, and a PCcan do all of those but someone needs to write thoseapplications for you first, one use-case at a time.But as these models get better and become multi-modal,the really transformative thesis is that one modelcan do ���any��� use-case without anyone having to writethe software for that task in particular.

Suppose you want to analyse this month���s customer cancellations,or dispute a parking ticket, or file your taxes - youcan ask an LLM, and it will work out what data youneed, find the right websites, ask you the right questions,parse a photo of your mortgage statement, fill in theforms and give you the answers. We could move ordersof magnitude more manual tasks into software, becauseyou don���t need to write software to do each of thosetasks one at a time. This, I think, is why Bill Gatessaid that this is the biggest thing since the GUI.That���s a lot more than a writing assistant.

It seems to me, though, that there are two kinds ofproblem with this thesis.

The first problem, Evans says, is that the models are still janky. They trip���all the time���on problems that are moderately complex or just a few degrees left of familiar. That’s a technical problem, and the systems are getting better at a startling clip.

The second problem is more twisty���and less clear how it will resolve: as a culture broadly, and as the tech industry specifically, our imaginations haven’t quite caught up with truly useful applications for LLMs.

It reminds me a little of the early days of Google, when we were so used to hand-crafting our solutions to problems that it took time to realise that you could ���just Google that���. Indeed, there were even books on how to use Google, just as today there are long essays and videos on how to learn ���prompt engineering.��� It took time to realise that you could turn this into a general, open-ended search problem, and just type roughly what you want instead of constructing complex logical boolean queries on vertical databases. This is also, perhaps, matching a classic pattern for the adoption of new technology: you start by making it fit the things you already do, where it���s easy and obvious to see that this is a use-case, if you have one, and then later, over time, you change the way you work to fit the new tool.

The arrival of startling new technologies often works this way, as we puzzle how to shoehorn them into old ways of doing things. In my essay Of Nerve and Imagination, I framed this less as a problem of imagination than of nerve���the cheek to step out of old assumptions of “how things are done” and into a new paradigm. I wrote that essay just as the Apple Watch and other smartwatches were landing, adding yet another device to a busy ecosystem. Here’s what I said then:

The significance of new combinations tends to escape us. When someone embeds a computer inside a watch, it���s all too natural for us to assume that it will be used like either a computer or a watch. A smartphone on your wrist! A failure of nerve prevents us from imagining the entirely new thing that this combination might represent. The habits of the original technology blind us to the potential opportunities of the new.

Today���s combinations are especially hard to parse because they���re no longer about individual instances of technology. The potential of a smartwatch, for example, hinges not only on the combination of its component parts but on its combination with other smart and dumb objects in our lives.

As we weigh the role of the smartwatch, we have to muster the nerve to imagine: How might it talk to other devices? How can it interact with the physical world? What does it mean to wear data? How might the watch signal identity in the digital world as we move through the physical? How might a gesture or flick of the wrist trigger action around me? What becomes possible if smart watches are on millions of wrists? What are the social implications? What new behaviors will the watch channel and shape? How will it change the way I use other devices? How might it knit them together?

As we begin to embed technology into everything���when anything can be an interface���we can no longer judge each new gadget on its own. The success of any new interface depends on how it controls, reflects, shares, or behaves in a growing community of social devices.

Similarly, how do LLMs fit into a growing community of interfaces, services, and indeed other LLMs? As we confront a new and far more transformational technology in Generative AI, it’s up to designers and product folks to summon the nerve to understand not only how it fits into our tech ecosystem, but how it changes the way we work or think or interact.

Easier said than done, of course. And Evans writes that we’re still finding the right level for working with this technology as both users and product makers. Will we interact with these systems directly as general-purpose, “ask me anything” (or “ask me to do anything”) companions? Or will we instead focus on narrower applications, with interfaces wrapped around purpose-built AI to help focus and nail specific tasks? Can the LLMs themselves be responsible for presenting those interfaces, or do we need to imagine and build each application one at a time, as we traditionally have? There’s an ease and clarity to that narrow interface approach, Evans writes, but it diverges from loftier visions for what the AI interface might be.

Evans writes:

Looking for AI Use Cases | Benedict Evans

A GUI tells the users what they can do, but it also tells the computer everything we already know about the problem. Can the GUI itself be generative? Or do we need another whole generation of [spreadsheet inventor] Dan Bricklins to see the problem, and then turn it into apps, thousands of them, one at a time, each of them with some LLM somewhere under the hood?

On this basis, we would still have an orders of magnitude change in how much can be automated, and how many use-cases can be found for LLMs, but they still need to be found and built one by one. The change would be that these new use-cases would be things that are still automated one-at-a-time, but that could not have been automated before, or that would have needed far more software (and capital) to automate. That would make LLMs the new SQL, not the new HAL9000.

March 23, 2024

AI + Design: Figma Users Tell Us What���s Coming Next

Figma surveyed 1800+ of its users about their companies’ expectations and adoption of AI. Responses from this audience of designers, executives, and developers indicate that AI is making its way into most companies’ product pipelines, but the solutions they’re shipping are… uninspired.

Eighty-nine percent of respondents say AI will haveat least some impact on their company���s products andservices in the next 12 months; 37% say the impactwill be ���significant or transformative.��� The executivesoverseeing company decision-making are even more bullishand much more likely to see AI as ���important to company��goals.���

But this kind of thinking presents its own risk. Our surveysuggests AI is largely in the experimental phase ofdevelopment, with 72% of those who have built AI intoproducts saying it plays a minor or non-essential role.Perhaps as a result, most respondents feel it���s toosoon to tell if AI is making an impact. Just one thirdof those surveyed reported improvements to metricslike revenue, costs, or market share because of AI,and fewer than one third say they���re proud of whatthey��shipped.

Worth repeating: Fewer than one third say they’re proud of what they shipped. Figma also says that separate research has turned up “AI feature fatigue” among a general civilian audience of product end-users.

What I take from this is that there’s general confidence that “there’s some there there,” but what that means isn’t yet clear to most companies. There’s a big effort to jam AI into products without first figuring out the right problem to solve, or how to do it in an elegant way. Exhibit #1: chatbots bolted onto everything. Early steps have felt like missteps.

“AI feature fatigue” is a signal in itself. It says that there’s too much user-facing focus on the underlying technology instead of how it’s solving an actual problem. The best AI features don’t shout that they’re AI���they just quietly do the work and get out of the way.

Hey, design is hard. Creating new interaction models is even harder; it requires stepping away from known habits and “best practice” design patterns. That’s the work right now. Algorithm engineers and data scientists have shown us what’s possible with AI and machine learning. It’s up to designers to figure out what to do with it. It’s obviously more than slapping an “AI label” on it, or bolting on a chatbot. The survey suggests that product teams understand this, but haven’t yet landed on the right solutions.

This is a huge focus for us in our client work at Big Medium. Through workshops and product-design engagements, we’re helping our clients make sense of just what AI means for them. Not least, that means helping the designers we work with to understand AI as a design material���the problems it’s good at solving, the emergent design patterns that come out of that, and the ones that fall away.

As an industry, we’re entering a new chapter of digital experience. The growing pains are evident, but here at Big Medium, we’re seeing solid solutions emerge in product and interaction design.

AI + Design: Figma Users Tell Us What���s Coming Next | Figma BlogThis is the Moment to Reinvent Your Product

Alex Klein has been on a roll with UX opportunities for AI. At UX Collective, he asks: will you become an AI shark or fairy?

The sharks will prioritize AI that automates partsof their business and reduces cost. These organizationssmell the sweet, sweet efficiency gains in the water.And they���re salivating at AI���s promised ability tomaintain productivity with less payroll (aka people).

The fairies will prioritize AI that magically transformstheir products into something that is shockingly morevaluable for customers. These organizations will leverageAI to break free from the sameness of today���s digitalexperiences���in order to drive lifetime value and marketshare.

No, they���re not mutually exclusive. But every company willdevelop a culture that prioritizes one over the other.

I believe the sharks are making a big mistake: they willcommoditize their product precisely when its potential valueis exploding.

A broader way to name this difference of approach: will you use AI to get better/faster at things you do already, or will you invent new ways to do things that weren’t previously possible (and maybe not just new “ways”���maybe new “things” entirely)?

Both are entirely legit, by the way. A focus on efficiency will produce more predictable ROI (safe, known), while a focus on new paradigms can uncover opportunities that could be exponentially more valuable… but also maybe not (future-facing, uncertain). The good news: exploring those paradigms in the right way can reduce that uncertainty quickly.

I think of four categories of opportunities that AI and machine learning afford, and the most successful companies will explore all of them:

Be smarter/faster with problems we already solve. The machines are great at learning from example. Show the robots how to do something enough times, and they’ll blaze through the task.

Solve new problems, ask new questions. As the robots understand their worlds with more nuance, they can tackle tasks that weren’t previously possible. Instead of searching by keyword, for example, machines can now search by sentiment or urgency (think customer service queues). Or instead of offering a series of complex decision menus, the machines can propose one or more outcomes, or just do the task for you.

Tap new data sources. The robots can now understand all the messy ways that humans communicate, unlocking information that was previously opaque to them. Speech, handwriting, video, photos, sketches, facial expression… all are available not only as data but as surfaces for interaction.

See invisible patterns, make new connections. AI and machine learning are vast pattern-matching systems that see the world in clusters and vectors and probabilities that our human brains don’t easily discern. How can we partner with them to act on these useful new signals?

Klein’s “sharks” focus on the first item above, while the “fairies” focus on the transformative possibilities of the last three.

That first efficiency-focused opportunity can be a great place to start with AI and machine learning. The problems and solutions are familiar, and the returns fairly obvious. For digital leaders confronting lean times, enlisting the robots for efficiency has to be a focus. And indeed, we’re doing a ton of that at Big Medium with how we use AI to build and maintain design systems.

But focusing solely on efficiency ignores the fact that we’ve already entered a new era of digital experience that will solve new problems in dramatically new ways for both company and customer. Some organizations have been living in that era for a while, and their algorithms already ease and animate everyday aspects of our lives (for better and for worse). Even there, we’re only getting started.

Sentient Design is my term for this emerging future of AI-mediated interfaces���experiences that feel almost self-aware in their response to user needs. In Big Medium’s product design projects, we’re helping our clients explore and capitalize on these emerging Sentient Design patterns���as embedded features or as wholesale products.

Companion/agent experiences are one novel aspect of that work, and Klein offers several useful examples of this approach with what he calls “software as a partnership.” There are several other strains of Sentient Design that we’re building into products and features, too, and they’re proving out. We’ll be sharing more of those design patterns here, stay tuned!

Meanwhile, if your team isn’t yet working with AI, it’s time. And if you’re still in the efficiency phase, get comfortable with the uncomfortable next step of reinvention.

This Is the Moment To Reinvent Your Product | UX CollectiveMarch 22, 2024

The 3 Capabilities Designers Need To Build for the AI Era

At UX Collective, Alex Klein shares three capabilities designers need to build for the AI era:

AI strategy: how can we use AI to solve legit customer problems (not just bolted-on “we have AI!” features)?AI interaction design: what new experiences (and risks) does AI introduce?Model design: prompt-writing means that designers can collaborate with engineers to guide how algorithms work; how can we use designerly skills to improve models?I agree with all of it, but I share special excitement around the new problems and emerging interaction models that AI invites us to address and explore. I love the way Klein puts it, and why I’m sharing his article here:

We���ve moved from designing ���waterslides,��� where wefocused on minimizing friction and ensuring fluid flow��� to ���wave pools,��� where there is no clear path andevery user engages in a unique way.

Over the past several years, the more that I’ve worked with AI and machine learning���with robot-generated content and robot-generated interaction���the more I’ve had to accept that I’m not in control of that experience as a designer. And that’s new. Interaction designers have traditionally designed a fixed path through information and interactions that we control and define. Now, when we allow the humans and machines to interact directly, they create their own experience outside of the tightly constrained paths we’re accustomed to providing.

We haven’t completely lost control, of course. We can choose when and where to allow this free-form interaction, blending those opportunities within controlled interaction paths. This has some implications that are worth exploring in both personal practice and as an industry. We’ve been working in all of these areas in our product work at Big Medium:

Sentient design. This is the term I’ve been using for AI-mediated interfaces. When the robots take on the responsibility for responding to humans, what becomes possible? What AI-facilitated experiences lie beyond the current fascination with chatbots? How might the systems themselves morph and adapt to present interfaces and interaction based on the user’s immediate need and interest? This doesn’t mean that every interface becomes a fever dream of information and interaction, but it does mean moving away from fixed templates and set UI patterns.

Defensive design. We’re used to designing for success and the happy path. When we let humans and robots interact directly, we have to shift to designing for failure and uncertainty. We have to design defensively, consider what could go wrong, how to prevent those issues where we can, and provide a gentle landing when we fail.

Persona-less design. As we get the very real ability to respond to users in a hyper-personalized way, do personas still matter? Is it relevant or useful to define broad categories of people or mindsets, when our systems are capable of addressing the individual and their mindset in the moment? UX tools like personas and journey maps may need a rethink. At the very least, we have to reconsider how we use them and in which contexts of our product design and strategy. As always, let’s understand whether our tools still fit the job. It might be that the robots tell us more about our users than we can tell the robots.

These are exciting times, and we’re learning a ton. At Big Medium, even though we’ve been working for years with machine learning and AI, we’re discovering new interaction models every day���and fresh opportunities to collaborate with the robots. We’re entering a new chapter of user experience and interaction design. It’s definitely a moment to explore, think big, and splash in puddles���or as Klein might put it, leave the waterslide to take a swim in the wave pool.

The 3 Capabilities Designers Need To Build for the AI Era | UX CollectiveMarch 14, 2024

When will AI Replace Us?

Who’s not afraid that AI will replace their job? In his talk, Big Medium’s Kevin Coyle shows us how this isn’t a new fear and how AI can be our new colleagues, and not our replacements. These new colleagues make lots of mistakes (as Kevin hilariously points out) but your team can start using AI today (seriously!) to guide them in the right direction.

March 13, 2024

What's Next for a Global Design System

This article was originally published at bradfrost.com.

Looking for help? If you’re planning, building, or evolving an enterprise design system, that’s what we do. Get in touch.

I recently published an article outlining the need for a��Global Design System. In my post, I wrote, “A Global Design System would improve the quality and accessibility of the world’s web experiences, save the world’s web designers and developers millions of hours, and make better use of our collective human potential.”

I’m thrilled to report back that many, many people feel the same. The response to this idea has been overwhelmingly positive, with people chiming in with responses like:

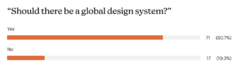

“Hell yeah!”“I’ve been saying this for years!”“This would save us so much effort!”“I recently started my new design system job and am disheartened to effectively be rebuilding the same thing I did in my last company.”“At my agency, I literally have 3 developers implementing accordion components in 3 separate (but essentially the same) projects.”“I find it so hard and confusing to find the most accessible components to reach for; I wish there were official accessible components to use.”“I’d love to not have to think about markup as much as I do now.”I was recently a guest on��Ben Callahan’s The Question, and he posed the question “should there be a Global Design System?” The results were overwhelmingly positive:

The thought of having a trustworthy, reliable, and capital-O Official Global Design System is clearly attractive to a lot of people. I agree! But even us proponents aren’t so naive to believe the creation of a Global Design System wouldn’t be without plenty of effort, alignment, and challenges.

In addition to many of the positive responses, I heard plenty of skepticism, open questions, and apprehension. So much of it is valid and shared by me!��Chris Coyier published a great post��that sums up a lot of it, and we were able to��dive into things together on ShopTalk Show. In this post, I’d like to dig into of the feedback and skepticism, and also share an update on some of the progress that’s been made so far.

I’ll go through some of the themes that I heard and address them as best as I can. Here goes!

“We already have a global design system.”Isn’t every open-source design system a “global design system”? Aren’t the people making them trying to make them as useful as possible for as many people as possible? If that’s right, and thus they have failed, why did they fail? What are they doing that doesn’t map to the philosophy of a global design system?

This is true! Open source design systems aim to be useful for as many people as possible. In��my original post��I explain some of the challenges of existing solutions:

These solutions were (understandably!) created with a specific organization’s specific goals & considerations in mind. The architecture, conventions, and priorities of these libraries are tuned to the organization it serves; they don’t take into account the sheer breadth of the world’s UI use cases.They nearly always come with a specific default aesthetic.��If you adopt Material Design, for example, your products will look like Google’s products. These libraries can be configurable, which is great, but themeabilitiy has limits and often results in many teams fighting the default look-and-feel to achieve custom results. In our experience, this is where folks end up creating a big mess.

Existing solutions haven’t “failed”, but none are positioned as a formal standard and lack the authority beyond their corporate/open-source reputation. They are de facto standards, and while that isn’t a terrible thing, it still leads to duplicative effort and requires consumers to go comparison shopping when searching for a sound solution.

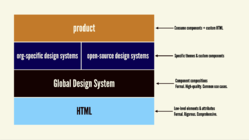

A Global Design System is less about the “what” and more about the “who” and “where”.��Nearly all of the popular open-source systems out there are perfectly fine from a component/feature/architecture perspective. The goal of a Global Design System is not to create a sibling to these existing systems, but to introduce a new canonical, more formal layer that can feed into these systems and beyond.

Isn’t this just HTML?Isn’t HTML the Global Design System? Shouldn’t missing components simply be added to HTML? I discuss this at length in��the original post:

Thanks to the tireless work of browser folks and standards bodies, I think that by and large we have most HTML elements and primitives in place to make most common web user interfaces.��What we need now are more prefabricated UI components��that abstract away much of the close-to-the-metal HTML and give developers composed, ready-to-use modules to drop into their projects.

In my opinion, HTML already has what we need, and it could be overkill to flood the HTML spec with��<badge>��and��<card>��and��<textfield>��and��<alert>��et al. Popular design system components tend to be more��opinionated compositions��rather than low-level elements. Moreover, the standards process needs to account for every use case since decisions are cooked into the very fabric of the web, which I explain in my earlier post:

The HTML standards process is necessarily slow, deliberate, and comprehensive, so a Global Design System layer on top of HTML can pragmatically help developers get things done now while also creating a path to future inclusion in the HTML spec if applicable.

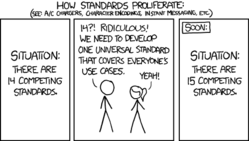

xkcd standards comicUnsurprisingly,��this classic XKCD comic��has been brought up plenty of times after I’ve shared the idea of a Global Design System:

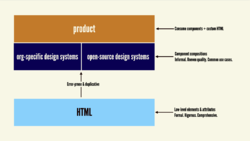

One of the most challenging aspects of articulating this idea is that it differs from the current paradigm. The proposal isn’t to create a better Bootstrap. The proposal isn’t to create an alternative to HTML. In my view, there’s a layer missing in between the base HTML layer and the myriad design system implementations out there:

The thought is that a Global Design System can help bridge the gap between HTML and existing design systems. Capture and centralize the components we see organizations building and rebuilding ad nauseam under one roof that is blessed by the appropriate organizations of the web.

So yeah, the goal is not to create a competing standard, but to introduce a new layer in order fill a gap in the landscape.

“You’d have to account for every use case”Don’t get me wrong: creating a design system for the world would be hard work. But! While HTML needs to account for��every��possible use case, a Global Design System could aim to handle common use cases. From my earlier post:

If the Global Design System could provide solutions for the majority of use cases for a given component, that would be a huge win! But what if you have a need to make a custom SVG starburst button that does a backflip when you click on it? That’s fine! We still have the ability to make our own special pieces of UI the old-fashioned way. This is also why a layer on top of HTML might be a better approach than extending HTML itself; HTML��has to��account for all use cases, where a Web Component library can limit itself to the most common use cases.

After all, this is what we see in design systems all over the world. A design system doesn’t (and shouldn’t!) provide every solution for��all��tabs,��all��buttons, and��all��cards, but rather provides sensible solutions for the��boring, common use cases so that teams can instead focus on the things that warrant more effort and brain power. The hope is that pragmatism and focusing on commonplace solutions would expedite the process of getting this off the ground.

“Things will look the same!”Ah yes, the age-old “design systems are killing creativity” trope.

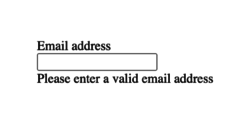

To be perfectly clear: a Global Design System would need to be generally unstyled and extremely themeable. A Global Design System component might look something like this out of the box:

The decision to make a door sky blue with fancy brass hinges or white with matte black hinges is a separate concern from “does the door open and close?”. A Global Design System would contain the proper semantics, relationships, accessibility, functionality, but leaves styling largely out of the equation. Think Global��Design System + CSS Zen Garden. Thanks to CSS custom properties, design token values can flow through the Global Design Systems components to accomplish any look and feel:

On the ShopTalk Show, we got into theming��and the fact that many people reach for design systems specifically because they provide a particular aesthetic. Which makes total sense! I could absolutely envision a Global Design System theme marketplace (using that term loosely, not necessarily implying a store) where people could choose a Tailwind-based theme, a Material Design theme, a Bootstrap theme, an��Open Props-based theme, or of course create whatever custom themes designed to meet the brand/design language needs of their organization. But again, I think it’s important that the system is “theme-less” default.

“Web Components have problems”In the��original post, I outline the reasons why it likely makes sense for a Global Design System to exist as a library of Web Components, which could contain something like this:

<www-text-field label="Email Address" type="email" required></www-text-field>Setting aside the specific details like attribute names (which would require careful research and consideration), the gist is that a Global Design System’s Web Component library would deliver the component markup, behavior, and any core styles to user developers.��Developers would interface with each Web Component’s API instead of having to author markup themselves, which would drastically reduce many low-level accessibility errors (e.g. associating a label with its corresponding input) and improve the quality and semantics of the world’s web experiences.

The unfortunate reality is that Web Components currently require JavaScript to deliver this abstraction. What would be��awesome��is to be able to simply wire Web Components up and have them Just Work, even if JS fails��for whatever reason. It would be awesome if something like this Just Worked:

<script type="module" src="path/to/global-design-system.js"></script><form> <www-text-field label="First name"></w3c-textfield> <www-text-field label="Last name"></w3c-textfield> <www-text-field label="Email" type="email"></w3c-textfield> <www-textarea-field label="Comments"></w3c-textfield> <www-button variant="primary">Submit</w3c-button></form>Thankfully, much work has been done around��server-side rendering��for Web Components and��solutions exist. But unfortunately this requires extra work and configuration, which is a bit of a bummer as that currently limits the reach of a Global Design System.

And much as I love many peoples’ excitement around��HTML Web Components, this technique defeats the purpose of removing the burden of markup on consuming developers, doesn’t create clean abstractions, and complicates the delivery of updated design system components to users. There’s more to say about Web Components but that’s a post for another day.

Despite their current challenges, Web Components are part of the web platform and these current shortcomings will continue to be addressed by the super smart people who make these things happen. I’d hope that this whole effort could serve as a lens to make Web Components even more awesome.

Too flexible?In��Chris’s article, he wonders if a Global Design System would need to be so “flexible to the point of being useless.” I understand what Chris is saying, but I think that scores of popular design systems share a similar architectural shape, and that certain components need to be architected in an extremely composable way.��Bootstrap’s card,��Material’s card,��Lighting’s card, and other cards don’t dictate what goes in the box, they simply define the box. A design system card must be extremely flexible to account for so many varied use cases, but the defining the box as a component is still incredibly valuable. Like all design system components, the rigidity-vs-flexibility dial needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis. This holds true for a Global Design System.

“This would be hard to do.”Lol, yep.

Like most design system challenges, the true hurdles for a Global Design System have little to do with tech stack, API design, or feature set. Instead,��the challenges have everything to do with orchestrating and aligning people.

As mentioned before,��this effort is more a matter of “who” and “where” than “what”.��Getting the right people and organizations involved, formalizing this whole shebang, figuring out how to fund an effort like this, determining architecture and priority, and winning hearts and minds is the bulk of the work. And that’s just to get the thing off the ground!

This feels like a good segue into a status report and next steps on this whole effort.

The challenges around creating a Global Design System have everything to do with orchestrating and aligning people.Status report

Since publishing my post, I was able to connect with the inimitable��Greg Whitworth, the chair of��OpenUI. For years, Greg and the merry folks who participate in OpenUI have been living in between the worlds of popular design systems and the W3C. Their tireless work,��research,��component matrix, and��proposals��have paved the way for standardization of widely-implemented UI components.

They’re well-positioned for an effort like this, and it seems like once upon a time OpenUI even had aspirations of creating a Web Component library to give some teeth the specifications they’ve been developing. Greg and I had a great initial conversation, and we just had another meeting with more members to discuss the idea. There’s been some great validation, some healthy skepticism, and some legitimately tough questions around this whole thing. These are exactly the types of conversations that should be happening, so I’m glad we’re having them!

Next stepsI’ve taught tens of thousands of people all over the world about the soup-to-nuts process of getting a successful design system off the ground. I tend to break the process down into these general phases:

SellKickoffPlanCreateLaunchGovern(Keep in mind this often isn’t a linear process; selling is never done!)

The creation of a Global Design System would follow this same process, albeit through a different lens. We’re still very much in the selling phase, and the next steps will require getting some alignment and traction with the appropriate organizations. I reckon continuing the conversation with OpenUI will bear fruit, and hey!��They have a Discord; you can join too��and get involved.

Many, many people have reached out with some form of “I have insights/research/design/code I’d love to share whatever would help this effort.” Which is AWESOME. While it may be a bit premature to start digging into specific solutions or architecture, I think this enthusiasm a real testament to the legitimacy of this idea. It’s all very encouraging.

I truly feel like we can dramatically improve the world’s web experiences while making better use of our collective human potential.��I’m looking forward to keeping the conversation going, and would love to hear your thoughts, skepticism, and ideas around the creation of a Global Design System.

March 6, 2024

AI and Design Systems

We’ve all witnessed an avalanche of AI-powered tools flood the landscape over the last year and a half. At��Big Medium, we help complex organizations design at scale and pragmatically adopt new technologies, so naturally we’ve been putting AI tools through their paces in order to uncover opportunities to help people produce better digital products and work better together.

As we all know, design systems have proven to be effective tools that help organizations ship higher-quality user interfaces more efficiently.��We’re finding that this new crop of AI tools can help supercharge design system efforts across many categories, and we’re starting to help our clients use AI to do exactly that.��Our resident AI expert,��Kevin Coyle, has been leading the charge in this wild new landscape, and we’ve all been exploring some promising ways that AI can assist in various aspects of design system creation and consumption. The future is here, and in this post we’ll demonstrate some of the ways we’re applying AI to the world of design systems, including:

Writing component codeTranslating components across frameworksWriting unit testsReviewing accessibilityWriting documentationMaking documentation more accessible/inclusiveOf course, these are only some of the potential use cases and there’s plenty more potential still to explore. In any case, let’s dig in!

component code generationOne of the most obvious examples of AI for design systems is to generate design system component code. Last year,��I wrote��that AI could be trained to act on instructions like this:

Make a new component called badge that has 4 variants: success, error, warning, and info. It has a text string prop, and a size prop that has sm and lg as available options. The background colors for the 4 variants should use the success, error, warning, and info background color design token variants.And splat goes the AI.

Turns out this is absolutely possible:

When you train a LLM on a design system’s codebase, conventions, syntax and documentation, you get a component boilerplate generator on steroids.��Human developers can then evaluate any outputted code, refine it (with or without the help of AI), and bring it over the finish line. In this scenario, AI becomes a junior developer contributing code for review like any other developer.��We guestimate this approach could help developers create components 40–90% faster than manually writing things from scratch.

AI can be trained on bespoke conventions, technology choices, and preferences in order to generate output that matches an organization’s existing standards.

It’s important to underscore that the AI can be trained on existing — often bespoke — conventions, technology choices, and language preferences.��In our work across organizations of all shapes and sizes, we’ve seen all manner of approaches, standards, syntax, and preferences baked into a design system codebase. Turns out that stuff really matters when it comes to creating a design system that can successfully take root within an organization. So while we’ve seen plenty of impressive AI-powered code generator products, they tend to produce things using specific technologies, tools, and syntax that may not be compatible with conventions and preferences found at many capital-E Enterprises. We’re skeptical of general-purpose AI code generators and err on the side of solutions that are closely tailored to the organization’s hard-won conventions and architecture.

component translationA different flavor of AI code generation involves translating code from one tech stack to another. Need to support Vue in addition to your existing Angular library? Want to create a Web Component library out of your existing React library?��Without the help of AI, translation is a labor-intensive and error-prone manual effort. But with AI, we’ve dramatically reduced both effort and error when migrating between tech stacks.

The video below demonstrates AI converting a badge Web Component built with LitElement into a React component in a matter of a few keystrokes.

Code and conventions that are shared between the tech stacks (SCSS, Storybook stories, component composition, doc blocks, props, state, and functionality) persist, and code and conventions that differ between tech stacks update in order to match the specific tech stack’s conventions.

This is powerful! Working with AI has brought our team closer to a true “write once, deploy anywhere” reality.��Similar to how tools like��Prettier��have disarmed the Spaces vs Tabs Holy Wars, we envision AI tools making specific implementation details like tech stack, conventions, syntax, and preferences less important. Instead, we can name or demonstrate requirements, and then the robots handle the implementation details—and port the code accordingly.

platform-specific conventionsWe’ve leaned on AI to assist with translating components to work with proprietary conventions in specific popular platforms. For example, we’ve used AI to convert a more standards-based��<a>��tag into��Next.js’s��<Link>��convention in a way that preserves a clean source of truth while also leaning into platform-specific optimizations.

It’s possible to take a clean design system codebase and use AI tools to create adaptations, wrappers, codemods, glue code, etc to help everything play nicely together. Our team is already doing all of these things with AI to great effect.

component testing and qaAs we’ve demonstrated, AI component code generation can be quite powerful. But a healthy level of skepticism is encouraged here! How can we be sure that component code — whether human or AI generated — is high quality and achieves the desired effect?��We like to think of AI as a smart-but-sometimes-unsophisticated junior developer.��That means we need to review their work and ask for revisions, just as you would with a human developer.

Testing and QA are critical activities that help ensure that a design system’s codebase is sturdy and sound. Setting up AI automation for this can also help keep us honest when the pressure is on.��Testing and QA often fall by the wayside when the going gets tough and teams are distracted by tough deadlines. AI can help make sure those tests keep getting written even as developers focus on shipping the project.

unit testsUnit tests are a special kind of chore that always felt like pseudo-code to me. “Click the accordion; did the accordion open? Now click it again; did it close?” Manually writing unit test code is something we’ve seen many teams struggle with, even if they know unit tests are important. Thankfully with AI, you can write prompts as unit test pseudo code and the AI will generate solid unit test code using whatever tools/syntax your team uses.

There may be some manual last-mile stuff to bring tests over the finish line, but I see this as a big step forward to help developers actually create component unit tests. This also means no more excuses for not having unit tests in place!

accessibility reviewThere are many great accessibility testing and auditing tools out there; AI adds another layer of accessibility QA to the puzzle:

AI-powered accessibility review can be integrated into a design system workflow, ensuring that component code is up to snuff before being released. And unlike existing automated accessibility testing that often surface a simple “pass vs fail” checklist, AI-powered accessibility testing can integrate your organization’s specific accessibility guidelines and also surface helpful context and framing for best practices. We like this as this additional context and framing can really help teams grow their accessibility understanding and skills. Hooray!

documentationHere’s the painful truth about documentation: nobody likes authoring it, and nobody likes reading it. But documentation is also critical to a design system’s success.��I liken it to Ikea furniture construction: sure you could technically build a piece of furniture with only the parts on hand, but you’ll likely screw it up, waste time, and get frustrated along the way. Maybe AI can help solve the documentation paradox?

documentation authoringAuthoring design system documentation by hand is a laborious, painful task. Teams are tasked with authoring pithy component descriptions, providing a visual specification, detailing each component’s API names and values, writing usage guidelines, and more. This information is incredibly helpful for design system consumers, contributors, and other stakeholders, but again, it’s all a pain in the butt to create. Moreover, documentation risks falling out of sync with the design system’s design and code library, and also has

If LLMs can generate entire novels, they certainly would have no problem generating some words about some well-trodden UI components.��The gist is to get AI to extract human-friendly documentation from design files, code libraries, and any other relevant sources (user research, personas, analytics, etc).��And just as with code generation,��LLMs can learn your organization’s specific conventions so documentation is custom tailored to your reality.��Pretty dang cool.

Moreover, when this AI-powered documentation is wired up to the teams’ workflows, the documentation can always represent reality and doesn’t get stale.

documentation viewingIn Douglas Adam’s Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, a��Babel fish��“can be placed in someone’s ear in order for them to be able to hear any language translated into their first language.” Indeed, many emerging AI technologies get awfully close to the sci-fi dream of real-time language translation.��But beyond��linguistic��language, design systems need to account for language differences between disciplines, experiences, and other contexts.

Design systems promise to deliver a shared language, but current design system documentation tends to be static and either too specific or too general to be useful for the myriad stakeholders that make up a digital organization. Wouldn’t it be cool if design system documentation morphed itself into a form that’s custom-fit to the individual looking for guidance? AI can be the babel fish that speaks in the manner and lingo that you personally need things to be explained.

AI can tailor design system documentation to the individual, taking into account their discipline, their skill level, their context, and even their preferred spoken/written language.

A junior-level designer understands the design system in a different way than a senior-level designer. A consuming front-end developer has different goals than a consuming designer.��AI can address this by tailoring the design system’s documentation to the individual: their discipline, their skill level, their context, and yes even their preferred spoken/written language.

Perhaps this AI-powered personalized guidance can help design systems realize the lofty goal of delivering a shared vocabulary across a digital organization?

principles and considerationsAs we’ve demonstrated here, AI tools can supercharge many facets of design system work. Of course it’s critical to stress that all of this is emerging technology, has the potential to do a lot of harm, and should be handled with care.��A human-centric mindset along with a healthy level of skepticism (especially in these early days!) should be employed when wielding these new tools.

Wielding AI tools requires a human-centric mindset along with a healthy dose of skepticism.

At Big Medium, we’re formulating some guiding principles and important considerations as we dig into these technologies:

Respect��– With all of our work, we want to respect peoples’ time, energy, and talents. AI can be wielded in many ways and has the potential to stomp all over our craft and our humanity. How can we let the machines take over our drudgery and free us up for more important, thoughtful, and fulfilling work? How can AI elevate and enhance our work?Org-specific solutions��– Design systems need to be tuned to the needs of a specific organization in order to be successful. AI can help evangelize “this is how we do things here”, but in order to do so these AI tools need to be internalize a specific organization’s culture, people, needs, technology, architecture, tools, and preferences.Security and privacy��– Related to the above point, in order for AI to be successfully integrated into an organization’s workflow, it needs to clear a high bar for security and privacy. Security is critical, and AI is rightly sounding alarm bells across the enterprise landscape. We feel strongly that on-premises AI tools are preferred over chucking an organization’s intellectual property into ChatGPT.Human-owned input and output��– It’s crucial for humans to control what gets fed into AI, and it’s crucial for humans to have the ability to modify/extend/fix any AI-generated output. While AI itself tends to be a black box, organizations should have full control over the input materials that the AIs are trained on, and should have full control over any outputted materials. Human team members can coach the AI, similar to how they might train a smart-yet-naive junior team member.Predictability and reliability��– Any AI tool needs to produce predictable, reliable results in order to be allowed anywhere near��critical front-end infrastructure��at an organization. Training AI on an organization’s specific conventions is an important first step, but then it takes some finessing refining, and evolving to ensure the AI systems behave in a reliable manner.Enhancement vs replacement��– Teams shouldn’t have to throw away all of their hard-earned knowledge, architecture, and assets in order to make use of AI. AI should work with the grain of hard-earned solutions and architecture, and teams should feel like AI enhances their work versus replacing their jobs.Of course, these principles and considerations aren’t exhaustive, and we fully expect them to change and evolve as the landscape continues to shift.

a brave new worldAs we’ve demonstrated here, there’s so much potential to integrate AI into many facets of design systems work. What we’ve shared is by no means comprehensive; for instance, we haven’t shared much around how AI impacts the world of UX and visual designers. There’s also plenty more cooking in the lab; Kevin the AI wizard is conjuring up some downright inventive AI solutions that make the demos shared here look like child’s play. And of course we’re all witnessing the AI Big Bang unfold, so the landscape, capabilities, and tools will continue to evolve. It feels inevitable that the world of design systems — along with the rest of the world! — will be shaped by the evolution of AI technologies.

Does your organization need help integrating AI into your design system operation? We can help! Big Medium helps complex organizations adopt new technologies and workflows while also building and shipping great digital products. Feel free to��get in touch!

February 19, 2024

A Coder Considers the Waning Days of the Craft

In the New Yorker, writer and programmer James Somers shares his personal journey discovering just how good AI is at writing code���and what this might mean both individually and for the industry: A Coder Considers the Waning Days of the Craft. ���Coding has always felt to me like an endlessly deep and rich domain. Now I find myself wanting to write a eulogy for it,��� he writes. ���What will become of this thing I���ve given so much of my life to?���

Software engineers, as a species, love automation. Inevitably, the best of them build tools that make other kinds of work obsolete. This very instinct explained why we were so well taken care of: code had immense leverage. One piece of software could affect the work of millions of people. Naturally, this sometimes displaced programmers themselves. We were to think of these advances as a tide coming in, nipping at our bare feet. So long as we kept learning we would stay dry. Sound advice���until there���s a tsunami.

Somers travels through several stages of amazement (and grief?) as he gets GPT–4 to produce working code in seconds that would normally take him hours or days���or sometimes that he doubts he’d be capable of at all. If the robots are already so good at writing production-ready code, then what’s the future of the human coder?

Here at Big Medium, we’re wrestling with the same stuff. We’re already using AI (and helping our clients to do the same) to do production engineering that we ourselves used to do: writing front-end code, translating code from one web framework to another, evaluating code quality, writing automated tests. It’s clear that these systems outstrip us for speed and, in some ways, technical execution.

It feels to me, though, that it’s less our jobs that are being displaced than where our attention is focused. We have a new and powerful set of tools that give us room to focus more on the ���what��� and the ���why��� while we let the robots worry about the ���how.��� But our new robot colleagues still need some hand-holding along the way. In 2018, Benedict Evans wrote that machine learning ���gives you infinite interns, or, perhaps, infinite ten year olds������powerful but, in important ways, unsophisticated. AI has come a long, long way in the six years since, but it still misses the big picture and fails to understand human context in a general and reliable way.

Somers writes:

You can���t just say to the A.I., ���Solve my problem.��� That day may come, but for now it is more like an instrument you must learn to play. You have to specify what you want carefully, as though talking to a beginner. ��� I found myself asking GPT–4 to do too much at once, watching it fail, and then starting over. Each time, my prompts became less ambitious. By the end of the conversation, I wasn���t talking about search or highlighting; I had broken the problem into specific, abstract, unambiguous sub-problems that, together, would give me what I wanted.

Once again, technology is pushing our attention higher up the stack. Instead of writing the code, we’re defining the goals���and the approach to meet those goals. It’s less about how the car is built and more about where we want to drive it. That means the implementation details become… well, details. As I wrote in Do More With Less, ���Done right, this relieves us of nitty-gritty, error-prone, and repetitive production work and frees us to do higher-order thinking, posing new questions that solve bigger problems. This means our teams will eventually engage in more human inquiry and less technical implementation: more emphasis on research, requirements, and outcomes and less emphasis on specific outputs. In other words, teams will focus more on the right thing to do���and less on how to do it. The robots will take care of the how.���

And that seems to be where Somers lands, too:

A Coder Considers the Waning Days of the Craft | The New YorkerThe thing I���m relatively good at is knowing what���s worth building, what users like, how to communicate both technically and humanely. A friend of mine has called this A.I. moment ���the revenge of the so-so programmer.��� As coding per se begins to matter less, maybe softer skills will shine.