Josh Clark's Blog, page 15

August 2, 2017

In the AI Age, ���Being Smart��� Will Mean Something Completely Different

As machines become better than people at so many things, the natural question is what’s left for humans���and indeed what makes us human in the first place? Or more practically: what is the future of work for humans if machines are smarter than us in so many ways? Writing for Harvard Business Review, Ed Hess suggests that the answer is in shifting the meaning of human smarts away from information recall, pattern-matching, fast learning���and even accuracy.

What is needed is a new definition of being smart,

one that promotes higher levels of human thinking and

emotional engagement. The new smart will be determined

not by what or how you know but by the quality of your

thinking, listening, relating, collaborating, and learning.

Quantity is replaced by quality. And that shift will

enable us to focus on the hard work of taking our cognitive

and emotional skills to a much higher level.

We will spend more time training to be open-minded

and learning to update our beliefs in response to new

data. We will practice adjusting after our mistakes,

and we will invest more in the skills traditionally

associated with emotional intelligence. The new smart

will be about trying to overcome the two big inhibitors

of critical thinking and team collaboration: our ego

and our fears. Doing so will make it easier to perceive

reality as it is, rather than as we wish it to be.

In short, we will embrace humility. That is how we

humans will add value in a world of smart technology.

Harvard Business Review | In the AI Age, ���Being Smart��� Will Mean Something Completely Different

July 20, 2017

Designing for Touch���in French! And Chinese!

Designing for Touch is now available in Chinese, French, and the original English.

I always feel a giddy cosmopolitan flush when one of my books is published in a new language. (Hey if I can’t manage to a cosmopolitan swagger, at least my books can look the part.)

And so I’m feeling especially je ne sais quoi about the publication of Designing for Touch in France and���new this summer���in China. Many thanks to translators Charles Robert and Zou Zheng (aka “C7210”) for their remarkable work on these two editions.

You can snap up any of these editions at the links below:

French: Design Tactile

Chinese: ������������:������������������������������������

English: Designing for Touch

Designing for Touch explores all the ways that touchscreen UX goes way beyond making buttons bigger for fat fingers. Designers have to revisit���and in many cases chuck out���the common solutions of the last thirty years of traditional interface design. In this book, you���ll discover entirely new methods, including design patterns, touchscreen metrics, ergonomic guidelines, and interaction metaphors that you can use in your websites and apps right now. The future is in your hands.

The Design System and Your Future Self

I had a great time talking design systems this week with Anna Debenham and Brad Frost on their Style Guide podcast.

Topics included: how to adapt design systems to an organization���s workflow and culture; the humility required to build wonderfully boring design systems; and the way that design systems will evolve to capture emerging interfaces.

All of these points circle the most important role of design systems: easing future work. Here���s what I had to say about that:

I do have a focus on designing for what’s next and how do we prepare organizations and products for what appear to be the emerging technologies that are likely to be really important in the next year or two. I do think that a really important thing about design systems and pattern libraries is being kind to your future self. It���s creating documentation, so that for the next project, my colleague or me, I’ll have all of this stuff at hand. ��� The way that I think of design system work writ large is that it is a container of institutional knowledge; it is a collection of solved problems and an example of the best of what a company does when it comes to design. ���

It takes less and less imagination now to see that things like speech in particular, but also some artificial intelligence aspects, are going to be coming into these [projects], that our interactions are going to go well beyond keyboard and mouse, as we’ve already seen with touchscreens. ��� What that means is that we’ll have an explosion of design best practices for each of these new channels, and we have to get a lot better at documenting all of them. And that’s what pattern libraries and design systems are great at. ���

What is emerging with all of this design system work is just how many disciplines and kinds of brains and kinds of creativity go into creating large and complex design solutions.

Listen to the whole podcast or read the transcript. Or hey why wait: just subscribe to the Style Guide podcast (iTunes or feed) so that you don���t miss an episode. Anna and Brad are doing great work to surface the best ideas and techniques for pattern libraries, style guides, and design systems. So good.

Does your company need a design system to bring order to a disconnected set of apps and websites? Or to capture emerging best practices for the latest interfaces? Big Medium can help with workshops, executive sessions, or a full-blown design engagement. Get in touch.

July 9, 2017

In a Few Years, No Investors Are Going To Be Looking for AI Startups

Frank Chen of Andreessen Horowitz suggests that while machine learning and AI are today’s new hotness, they’re bound to be the humdrum norm in just a few short years. Products that don’t have it baked in will seem oddly quaint:

Not having state-of-the-art AI techniques powering

their software would be like not having a relational

database in their tech stack in 1980 or not having

a rich Windows client in 1987 or not having a Web-based

front end in 1995 or not being cloud native in 2004

or not having a mobile app in 2009. In other words,

in a small handful of years, software without AI will

be unthinkable.

So ambitious founders will need to invest some other

way to differentiate themselves from the crowd���������and

investors will be looking for other ways to decide

whether to fund a startup. And investors will stop

looking for AI-powered startups in exactly the same

way they don���t look for database-inside or cloud-native

or mobile-first startups anymore. All those things

are just assumed.

As Chen says, this feels like mobile just a few years ago. Just as mobile was the oxygen feeding emerging interactions and capabilities, machine learning is doing the same now. All the new interactions, all the new digital superpowers, they’re all being fueled by machine learning and algorithms.

In 2012, I wrote a chapter for The Mobile Book, for which Jeremy Keith wrote a prescient foreword. ���This book is an artefact of its time,��� he wrote. ���There will come a time when this book will no longer be necessary, when designing and developing for mobile will simply be part and parcel of every Web worker���s lot.���

Yep, five years later, mobile is an assumed part of the job. If you were writing a “Machine Learning Book” today, you could borrow the same observation for the foreword. It’s time to get your game on now, since this will be an assumed capability in short order.

If you’re a designer wondering how you fit into all of this, I have some ideas: Design in the era of the algorithm.

In a Few Years, No Investors Are Going To Be Looking for AI Startups

Airlines Redesigning Uniforms Find Out How Complicated It Is

I’m a fan of the commitment, iteration and heavy testing that goes into the design of airline uniforms. Martha C. White reports for The New York Times that the process can take 2���3 years from start to finish.

Uniforms also have to reflect the realities of life

on the road, with fabric blends that resist stains

and wrinkles and can be laundered, if necessary, in

a hotel sink. They also need to keep the wearers comfortable,

whether their plane touches down in the summer in Maui

or in the winter in Minneapolis.

Before giving the new uniforms to employees, the airlines

conduct wear tests. The roughly 500 employees in American���s

test reported back on details that needed to be changed.

For example, Mr. Byrnes said, an initial dress prototype

included a back zipper, but flight attendants found

it challenging to reach. So the zipper was scuttled

in favor of buttons on the front.

For its 1,000-employee wear test, Delta solicited feedback

via surveys, focus groups, an internal Facebook page

and job shadowing, in which members of the design team

traveled with flight crews to get a firsthand view

of the demands of the job.

���We had about 160-plus changes to the uniform design���

as a result of those efforts, Mr. Dimbiloglu said.

The depth of the process makes sense because these uniforms define not only the company brand, but also impact the working life of thousands of people. Come to think of it, that’s true of pretty much any enterprise software, too. If you’re the designer of such things, are you bringing the same commitment to research, testing, and refinement to your software projects?

New York Times | Airlines Redesigning Uniforms Find Out How Complicated It Is

Uncovering Voice UI Design Patterns

The folks at Cooper are learning by doing as they experiment with building their own voice apps for Alexa and other platforms. As they’ve begun to encounter recurring problems, they’re taking note of the design patterns that solve them.

We���re trying to capture some of these patterns as we

work on voice UI design for young platforms like Alexa.

We identified five patterns and what they���re best suited

for here.

This is how the industry finds its way to best practices: experimenting, sharing solutions, and finally, putting good names to those solutions. Cooper is off to a good start with these design patterns:

A la carte menu

Secret menu

Confident command

Call and response

Educated guess

Cooper | Uncovering Voice UI Design Patterns

Surface Deep

Microsoft’s unconventional Surface Studio PC emerged from design process that is equally unconventional (but shouldn’t be).

Ross Ufberg takes a deep dive into the design process behind Microsoft’s hyper-swiveling Surface Studio, a high-concept device that turns the desktop PC into a drafting table. A key ingredient to the project’s breakthrough success seems to be the highly collaborative, cross-disciplinary team that they corralled into Microsoft’s Building 87 to invent the thing:

Under one roof, Microsoft has united a team of designers,

engineers, and prototypers, and invested heavily in

infrastructure and equipment, so that Building 87 can

be a self-contained hub, complete with manufacturing

capabilities that usually would be located offsite

or outsourced. Having these capabilities close at hand

drastically cuts down on dead time, so that, in some

cases, mere hours after a designer sends a concept

down the hall to the prototypers, they can figure out

a way to embody that concept, and print it in 3D or

manufacture it on the spot. The model-making team can

then hand that iteration off to the mechanical engineers,

who assess the viability of the concept and figure

out ways to improve it. It���s sort of like one endless

feedback loop, with designers conceiving, prototypers

creating, engineers correcting, and back again to the

designers.

This is exactly the spirit of Big Medium’s own (far smaller) design teams. We have constant collaboration and feedback among product designers, visual designers, front-end designers, and developers. It’s not a linear process, but a constant conversation that blends experiments, false starts, grand leaps, successes, and gradual improvements. This turns out to be both faster and more creative.

In workshops and design engagements, we coach client organizations how to adopt this collaborative, iterative design process. Designers and developers often tell us at first that it feels unfamiliar, even uncomfortable, to collaborate across the entire design process���and especially when ideas are being formed. It’s natural to shy away from sharing before something is fully thought out. But that’s exactly where the most productive cross-disciplinary experiments happen.

One of Surface Studio’s signature design innovations is the hinge that lets it shift instantly from upright desktop monitor to a sloped, dial-and-stylus drafting board. In Ufberg’s telling, it wouldn’t have happened at all without a culture of cross-disciplinary experimentation.

���It is way easier to try something than tell somebody it can���t be done.���

When the idea of a hinge was first tossed out in a

brainstorming meeting, [mechanical engineering director Andrew] Hill tells me, ���there were ten

different people who said that it doesn���t make any

sense, it would be too complicated to make it work.

But then a couple weeks later, we got a prototype out

of our model shop where you could see the mechanism

starting to come together, and the people who were

saying it couldn���t be done started to come over and

be like ���Huh, maybe we could do something like this.������

I ask him if he was one of those doubters.

���One of the things that I found out about myself is

it is way easier to try something than tell somebody

it can���t be done,��� he confesses. ���There���s magic in

the suspension of disbelief. If you just do stuff that

you know you���re going to be able to do, you know where

you���re going to go. If you try something that you���re

not quite sure is going work, at least you���re exposed

to new problems and you get smarter in that way, and

in the good cases, you move the whole thing forward.���

In its first iteration, the hinge was just a piece

of cardboard glued crudely to a kickstand. But then,

the feedback loop kicked into place.

The bottom line: When in doubt��� don’t doubt. Build a quick prototype���the most low-fi thing you can create to test the concept���and then share it with people from other disciplines. It’s how you manage risk in an inherently risky exploration into the new.

That’s good advice not only for industrial design, but for pretty much anytime you’re really trying to make something new and better. And isn’t that all of us?

Need help transforming your organization���s design process for faster and more creative results? That’s what we do! Get in touch for a workshop, executive session, or design engagement.

Breakground Magazine | Surface Deep

Oil City High School 2017 Commencement Speech

Returning to scenes of youth is always complicated business, the stuff that makes high school reunions emotionally fraught. How have I changed, how haven’t I, and how do I express those things when I come home? I know Brad Frost was sweating these topics as he toiled over his commencement speech at the high school where he graduated 14 years ago.

Months before he gave the talk, he told me he was already nervous about it. Turns out he didn’t need to worry. In fact, the “what has/hasn’t changed” anxiety turned out to be central to his wonderful speech. I especially loved this message:

The things you will be doing in 14 years��� time will

no doubt be different than the things you���re doing

at this phase in your life. A recent study by the Department

of Labor showed that 65% of students going through

the education system today will work in jobs that haven���t

been invented yet. Think about that. That means that

the majority of today���s students ��� probably including

the majority of this graduating class ��� will end up

working in jobs that don���t presently exist. Technology

is advancing at a staggering rate, it���s disrupting

industries, it���s inventing new ones, and it���s constantly

changing the way we live and work.

When I was a kid, I didn���t say ���Mom, Dad, I want to be a web designer when I grow up!��� That wasn���t a thing. And yet that���s now how I spend most of my waking hours, and how I earn my living, and how I provide for my family.

Our daughter Nika is about to start her final year of high school, and she sometimes worries that she doesn’t yet have enough vision for what she’ll become in her life and career���that she’s behind. But she knows what she loves, and she has so many talents, so we try to reassure her that knowing her skills, values, and personality is far more important than knowing a vocation. Vocations shift far more quickly than the rest.

When I graduated from high school (30 years ago next year!), the web hadn’t been invented, mainstream email was years away, and phones were cabled to the wall. But even then, I had a passion for both storytelling and systems���and those have been the guiding threads of a career spanning many kinds of jobs, culminating (for now at least!) in work shaping experiences of and for connected devices.

The great thing about returning to scenes of youth is that sometimes���like Brad���you get to talk to the kids coming up behind you. You can share the advice you’d offer your younger self. Nice work, Brad.

Brad Frost | Oil City High School 2017 Commencement Speech

June 29, 2017

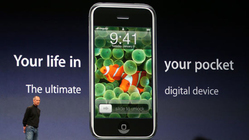

How iPhone Changed Computing���and Much More

Steve Jobs reveals the iPhone in June 2007.

The iPhone was the first time in my adult life that I saw my childhood notions of the future realized���and with good reason: it was (and still is) the future. Ten years ago today, the first iPhones arrived in customers��� hands, catalyzing a huge set of changes that are still playing out.

Android certainly shares the credit for everything that modern smartphones unlocked, but it was the iPhone that exploded the market, pioneered the new UI, created the app store, and even forced cell-network upgrades to support the new mobile era. The iPhone���s legacy is the smartphone legacy.

Here���s what that legacy looks like.

Real web browsing on mobile devices

The iPhone was the first popular device to make it easy to browse desktop websites on a mobile device. Before the iPhone, the mobile web experience was hobbled by crummy WAP sites, weird trackball cursors, or lousy text-only experiences navigated by keypad. The iPhone���s huge (for the era) screen and pinch-to-zoom interaction made it possible to see the whole web from your phone for the first time. The iPhone released the web from its desktop prison.

(For the iPhone���s first year, the only way to create an ���iPhone app��� was to build a web app, remember?)

Responsive web design

Suddenly we had more than one kind of screen to design for. The iPhone and the mobile explosion that followed was both opportunity and crisis. As an industry, we knew only how to pour services and content into one container at a time���each one purpose-built for a specific platform. As more and more devices and screen sizes arrived, however, we needed a new technique to make it manageable. Ethan Marcotte delivered that in the form of responsive web design in March 2010. The iPhone and its mobile mandate forced this deep change that has since transformed the method and perspective of web development.

Touch and other alternatives to mouse and keyboard

For over 30 years, we explored the digital world exclusively with these prosthetics called mouse, keyboard, and cursor. We nudged plastic bricks across our desks. We directed onscreen arrows to poke buttons from afar. We clicked icons. We pointed at pixels.

But with the iPhone, millions and then billions of people suddenly started holding those pixels in our hands. The whole world now wrangles touchscreens every day, all day. We now touch information itself: we stretch, crumple, drag, flick it aside. The design of digital interfaces is no longer just how a design looks but how it feels in the hand.

If the iPhone (and responsive design) jolted the industry with the simple truth that the web is not limited to a single output (the desktop screen), it also introduced another revelation: computing is not limited to a single input, either. Touch was the first wildly popular alternative to the mouse/keyboard monolith, but the iPhone and other smartphones have continued to introduce even more inputs, too. Mobile has normalized an intricate choreography of inputs that include camera, audio, GPS, natural gesture, and more.

Software is personal (and personality)

Once upon a time, applications used to be these gray, dreary affairs imposed upon you to do your mundane day-to-day chores. They were the stuff of spreadsheets and word processing and database records. The Web 2.0 era began to infuse software with more personality, but the iPhone blew it open and brought the idea of ���apps������truly personal software���to the masses. The iPhone made mainstream the idea that software could be fun, expressive. It changed the tone of digital interfaces.

No gizmo or gadget has ever inspired as much affection as the iPhone in its first years. The iPhone was the first truly personal computer���and not only because it was a beautiful little totem that was always with you. It was also a device that knew so much about you, even about what was around you or nearby. And it was awash in colorful and fun apps that you personally selected, curated, cared for. In those days, your home-screen icons said as much about you as the contents of your handbag, the clothes you wore, or the bobbleheads decorating your desk.

With Siri, the iPhone even made the device itself a personality, with the first widespread voice interface. Talking to machines is quickly becoming commonplace, and that trend first became truly popular on iPhone.

The world, appified

���There���s an app for that.��� When the app store arrived in 2008, nearly anything you could imagine could suddenly be delivered in tidy, cheerful packages called apps.

For years, phone makers had been trying to make phones behave like computers. Apple���s breakthrough was in choosing to make a computer first, reducing the phone itself to an app (and the device���s least interesting app at that).

And then everything else became an app, too. Smartphone apps absorbed and replaced cameras, paper maps, music players, flashlights, GPS gadgets, radio. ���Software is eating the world,��� Marc Andreessen wrote in 2011. It was the iPhone that cut the world up into tiny, tasty bites���obsoleting entire industries and devices along the way.

Your life? There’s an app for that.

A portal to all the people we care about

The iPhone has never been a ���phone,��� not really, but it���s always been a communicator. One of the reasons it���s so powerfully addictive is because it���s a portal to all the people we care about. Text and photos are the essential creative units of mobile devices, perfect for constant sharing of thoughts and activity. It���s no accident that social-media properties skyrocketed with the arrival of iPhone, but it also became an ideal container for more private conversations via technologies like Facetime, too. iPhone popularized the idea of computer as capsule for relationships both strong (family) and weak (twitter followers).

Information at the point of inspiration

The arrival of a capable networked mobile computer suddenly made the world���s information available at a whim. Now we can act on immediate impulse to get information or media or services or commerce. Snap that photo, record that conversation, consult that map.

This superpower is also mobile���s Achilles��� heel. Because the phone is available at the point of inspiration, it also carries us away from the very thing that inspired us. The more connected we are, the more disconnected we become from the world around us.

It turns out that the lure of on-demand information, play, and distraction is irresistible. On average, we spend nearly 20 percent of our waking hours staring into these tiny rectangles. I can���t help but think: maybe we mobile designers have done our jobs a little too well. And maybe ���engagement��� was the wrong goal to chase in the first place.

So I���m heartened by the possibilities of this still-emerging iPhone legacy:

Interaction with the point of inspiration

Instead of pulling us into our screens at the moment of inspiration, certain smartphone interactions encourage engagement with the world. The iPhone introduced and popularized sensor-based computing, direct interactions between your phone and your immediate environment. It began with simple location-based computing to tell you who or what was nearby. But it soon morphed into something more powerful: making sense of what���s right in front of you.

Remember the first time you saw Shazam identify a song? Or Google Translate transform a sign in your phone���s camera viewfinder into a different language? Or see a Pokemon materialize on the sidewalk?

Now that iOS 11 is about to bake an augmented-reality platform (ARkit) into the operating system itself, we may uncover still more new ways to interact with the point of inspiration.

With the steady march of machine learning and artificial intelligence, computers are getting better and better at making sense of the world immediately around us. Smartphone sensors are the funnels that gather that immediate data, and the iPhone was the device that made this feel… normal.

The iPhone should be remembered as the first mainstream internet of things device: a mundane object lit up with smarts thanks to a processor, a connection, and sensors. The phone has become the everyday bridge between digital and physical.

The iPhone changed the way we experience the world and each other���for better and for worse���and its story isn���t done. As these tiny computers get more powerful and gather/share more data, they���ll become even more deeply intimate and more revealingly public���our tiny but far-seeing windows into the world and ourselves.

June 28, 2017

So We Redid Our Charts���

Video analytics provider Mux overhauled their data visualizations and shared the process. The thinking and results make for a worthwhile read, but I was especially taken with the project’s framing questions:

When we wanted to revisit our charts, we looked at

them from both of these perspectives and asked ourselves:

Are we being truthful to our calculations? And, are

we presenting the data in a beautiful and sensible

manner?

I’m more convinced than ever: the presentation of data is just as important as the underlying algorithm.

Mux | So We Redid Our Charts���