Harry S. Dent Jr.'s Blog, page 178

October 13, 2014

Innovation After A Market Crash

I love history – especially history concerning the stock market and the world of finance. If you do the research you can get a good idea of what the markets are going to do, especially when you can apply a demographic cycle to the equation.

In 2013, as soon as I heard that David Stockman had released a new book… I knew I had to read it. I plowed through it in just five days. I read all 718 fact-filled pages. And I enjoyed the many vivid and interesting stories.

I knew that what he had to say in his book was important because I’ve heard his passionate comments before on television interviews… and when I met him in Fox’s New York studio.

His resume is nothing less than impressive. He’s was the budget director for Reagan and he worked at the highest levels of Salomon Brothers and Blackstone. He started his own firm and he’s been a major private equity investor.

This is a guy worth listening to.

A man with massive real-life experience in the world of politics, high finance and investing.

And it’s for those reasons, we asked him to be the keynote speaker at our Irrational Economic Summit this October 16 to 18 in Miami…

David couldn’t sing my tune on the perversity of government manipulation of markets and the economy more perfectly (what I call “the markets on crack”) if he tried.

David was kind enough to endorse my recent book. He said:

“I have worked at the highest levels of U.S. politics and see a disaster in the making as the government employs endless stimulus plans and bailouts that destroy the very free market capitalistic system that has made it the richest major country in the world. Harry Dent adds the reality of aging societies and slowing demographic trends to show why such reckless debt-driven policies are certain to fail.”

Thank you, David!

And I more than heartily endorse his book, as I have several times in past articles… and as I will continue to do in the future. Let me share some of the insights I’ve gleaned from his book.

War and InnovationsI’ll start today with perhaps the biggest insight I got from his incredible knowledge of the history of government finance in America. That is the underestimated effect World War I had in catapulting the U.S. into the global economy as a major new power and exporter.

The U.S. was an up-and-coming emerging country — much like China is today — after the American and Industrial Revolutions, and especially so as we surpassed England in GDP and began leading innovation in the late 1800s.

I’m talking about the invention of the phone by Bell to electrical innovations by Edison. Henry Ford took the lead in car manufacturing after the invention of the combustion engine in Germany. He came up with the Model T in 1907 and then the assembly line in 1914 — massive long-term innovations. That assembly line didn’t just catapult cars into mainstream affordability, but tractors that caused a farm revolution in productivity. If any single person helped to create the new middle-class factory worker, it was Ford.

But it was World War I that initially allowed the U.S. to leverage our innovations and growing production and agricultural capacity.

Due to the war, the allies suddenly needed our production capacity in these two areas because their attentions were diverted toward their war efforts. This made us a major exporter and catapulted our growth between 1914 and 1920. We also helped to finance that war and that boosted our growing financial institutions.

The When and WhyI always remind my readers of the major deflationary recession that occurred from 1920 into 1921. Everyone knows about the Great Depression, but almost no one knows about the very serious and deflationary downturn that preceded it by a decade.

It was David who gave me new insight as to why commodity prices peaked in 1920 and why such an extreme recession or mini-depression ensued.

After the war ended in 1918, European production and agricultural capacity came back on line. That created a glut in capacity, a drop in industrial and agricultural commodities, and a slowing in world trade.

That setback obviously hit the U.S. the worst. After all, we were the fastest growing exporter at the time.

Without David’s book, I wouldn’t have gained that deeper understanding of events during that time as quickly as I did.

That insight was worth more than the price of the book and the 20 hours it took of my time to read it.

So, I recommend you do the same. Read David’s book.

Even if you don’t have that much time, at least skim through it and find the sections that interest you. You won’t be disappointed.

The Great Deformation is simply the best book I’ve read on the history of finance and politics in America over the last century… and especially how governments have taken the easy way out and killed the very free market capitalist system that has created such unprecedented success in modern times.

David calls it “the corruption of capitalism in America.” I call it “killing the golden goose.”

So, don’t miss David Stockman at our IES conference in Miami this week October 16 to 18. He and I will speak on the first day and have a Q&A after. I can guarantee you it will be lively and provocative!

Harry

October 10, 2014

Government, Don’t Touch My Pension

Traditional pension plans have long been a solid vehicle for retirement, especially for government workers. But something is going on out on the West Coast.

The California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) is not just big, it’s colossal. The fund manages more than $250 billion, and is known for aggressively protecting its turf. If you owe the system money, they send enforcers to your door like mobsters, threatening to break bones and torch your car if you don’t pay up.

OK, I made that last part up, but it’s not too far off.

CalPERS goes after deadbeat cities and other entities that owe it money with a vengeance, which is why recent developments are so interesting. A bankruptcy judge presiding over the bankruptcy of the city of Stockton, CA. just told CalPERS that its entire claim of omnipotence is false. Not only can Stockton change what it pays CalPERS, but the pension system holds no higher claim on assets than other creditors like bondholders.

This wasn’t an opinion written by the court, but it was the judge’s reasoning as he spoke from the bench.

CalPERS is howling because if this becomes a precedent it could undermine the entire system. It could also serve as a blueprint for other cities and states to walk on their own obligations.

Many if not all municipal entities (cities, counties, etc.) in California offer pensions to their employees. California’s state constitution specifically bars any public entity from reneging on a pension obligation, which means that once an employee starts accruing benefits, they cannot be reduced, period. The cities and counties tend to use CalPERS to run their pensions because the size of the organization translates into lower operational expenses.

But the combination of these two things, inviolable pension obligations and the size of CalPERS, has led to something else — an almost mafia-like relationship between the pension system and the municipalities that it serves.

When a municipality hires CalPERS to run its pension, the municipality must sign a contract stating that no matter what any court, anywhere in the world might decide, the obligations of the municipality to CalPERS cannot be diminished or discharged. The pension system points to the constitution of the state of California for backup on this point.

When the city of Vallejo, CA went bankrupt several years ago, the town asked CalPERS to work with them on renegotiating pensions. The pension system told them to take a hike. Yes, other creditors would get much less than they were owed. And yes, in some cases that amounted to more than a 90% haircut. But pensions are protected by the state constitution, so there will be zero changes.

CalPERS told Vallejo that if the city chose to push the issue, then CalPERS would bring on the full force of its legal team. Obviously, Vallejo didn’t have any money to fight a protracted legal battle, the city was already bankrupt. In the end Vallejo caved to the demands of CalPERS, keeping their debts at 100% while crushing everyone else.

Stockton, CA is not asking the bankruptcy judge to change its obligation to CalPERS, because this city doesn’t want a fight with the pension system either. However, the judge overseeing the city’s bankruptcy must approve its plan, including how much is paid to each creditor. Stockton’s plan calls for paying CalPERS 100% of its claim.

The judge gave his view of CalPERS’ position in a statement from the bench. He noted that once an entity enters bankruptcy, it’s governed by federal law, not state law. Given that, there’s no claim in state law that can supersede the claims in bankruptcy, because that would mean that state law can supersede federal law, and that’s not the way it works.

So, no matter what agreement CalPERS made with the cities and states, once they’re accepted into bankruptcy all bets are off. It seems likely the judge won’t approve of a plan that puts CalPERS in a greatly superior position to other creditors, and that’s where the fight will start.

If CalPERS loses its “you-must-pay-us-everything” grip on municipalities, which would mean that state constitutional rights to pension benefits can be broken in bankruptcy, then a number of poorly funded California cities might try their chances in bankruptcy as well. And it wouldn’t stop there.

Cities, counties, and states around the country that are similarly positioned would all have a motivation to dive into bankruptcy. The current hole in public pensions is roughly $2 trillion. For many cities, counties, and even states, there’s no conceivable way that they’ll ever be able to pay everything that they owe.

But, as always, there’s the other side.

If Stockton, or any other city or state, is able to pay less than it owes to a pension fund, what happens to the retirees who are covered under that pension fund? That is the $64,000 question.

Years ago I wrote that eventually I think there will be a national backstop set up for public pensions, one that mirrors the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) which covers private pensions. Since such an organization would be brought to life specifically to deal with struggling pensions that are woefully underfunded, any guesses on where the money will come from to top up the funding?

Once again, American taxpayers will come to the rescue… whether they want to or not.

Rodney

October 9, 2014

The Market Cycle’s Slippery Slope

Will this bubble burst anytime soon? Will we have inflation or deflation? There are lots of questions being asked.

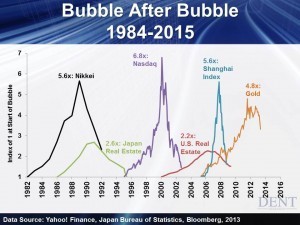

The inability for economists and financial analysts to understand the most basic principle of cycles is just beyond comprehension… especially since we’ve been in this bubble era since 1995. How could so many be arguing that we’re not in a bubble when we have seen one bubble after the next rise and then burst as they always do?

The Japanese stock bubble burst in 1990 and then Japanese real estate tanked in 1991. It’s been 19 years since their stocks dropped a whopping 80% and after 23 years real estate is still down 60%.

The tech bubble that peaked in 2000 crashed by 78% and it’ll likely crash again after approaching its highs. And when stocks proved fallible, investors rushed into real estate — the one thing that couldn’t go down. They couldn’t have made a greater mistake — it fell by 34% between 2006 and 2011 — with the worst sectors down by 55%. That really hurts when you are highly leveraged with a mortgage.

My promise here… even though it had a weak bounce: It will drop again (and don’t even get me going on China).

The chart below shows some of the more prominent bubbles.

The emerging markets bubble was as strong as the tech bubble that peaked in late 2007/mid-2008 and then dipped by 68%. It crashed 70% in China. China is still hovering around its 2008 lows today. Commodities peaked in mid-2008 and they still haven’t gotten back to those highs and will probably go much lower, according to our 30-year commodity cycle and it’s been reliable for nearly 200 years.

Then the last bastion was held by gold and silver. They were supposed to be the ideal investment strategy that would protect you in a downturn… according to the gold bugs, not us. That quickly turned into a not ideal strategy. We saw gold drop by 38% from its peak back in September 2011 and silver slid down by an unbelievable 63% since April of 2011 when we gave the major sell signal for the precious metals. There will be more to come in that scenario.

I don’t see how economists and analysts are blind to the Fed’s constant fueling of the bubble we’re in and that it will, not maybe but will burst. It couldn’t be more obvious. The denial factor grows stronger when bubbles are moving into the final stages and it’s a rampant symptom right now in a lot of people.

I’ve had to debate Ron Insana on CNBC many times. He categorizes the Fed’s policy in creating endless amounts of money out of thin air to solve all of our financial crises and problems as “enlightened policies.” How is that for delusion and denial?

It’s just mind-boggling.

I’m going to play devil’s advocate here for a second. If we’re going to print money… and it has no serious consequences… and it really is the new enlightened approach to economics, then why are we pussy footing around? Why don’t we print $17 trillion and pay off the national debt? Why don’t we print $10 trillion and pay off every household’s mortgage?

Or as Roseanne Barr recently joked in all of her typical political correctness: “Why don’t we give every broke person $10,000 a week? Then the rest of us can invest in liquor stores, casinos and porn websites.”

Ron Insana is actually one of the most intelligent people I debate on this topic but his view is still simply insane to me. Paul Krugman is the leading liberal economist and he thinks we should have printed much more money than we did.

If I’m not debating the “enlightened” ones, I’m hashing it out with the gold enthusiasts. They see hyperinflation, gold going to $5,000 plus and the dollar crashing to near zero. Did this happen in the last financial crisis? No, it didn’t. The dollar went up and gold and silver crashed.

Inflation is not the consequence. The consequence is preventing our economy from rebalancing unprecedented debt, financial leverage and speculation. The inevitable consequence is creating an even bigger bubble that will have to burst and it will do that soon.

Deflation is the trend and we saw the money supply in the U.S. actually contract 6% for a few months before the Fed stepped in with their unprecedented stimulus. They are inflating to fight deflation.

Even the central banks can’t keep this bubble going forever, and in fact, it seems to have expanded to about as far as it can go to me and stock gains have been minimal since the beginning of this year.

You need to prepare for another across-the-board bubble burst and the deepest downturn since the Great Depression with deflation… not inflation. It will fall deeper and it will last longer than it did in 2008.

This isn’t the time to listen to those leading politicians, economists and pundits who say we’re not in a bubble and we’re finally seeing a sustainable recovery.

Harry

October 8, 2014

We Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Debt

If only central bankers had the discipline of 4-year-olds.

In the 1960s, a group of psychologists at Stanford University wanted to test the ability of children to delay gratification. Using children in the university day care as the subjects, the psychologists would sit a child down at a table with a marshmallow on a plate. The child was told that he could eat the marshmallow whenever he wanted, but if he waited until the adult returned, he would get two marshmallows. Then the child was left alone in the room.

Some kids ate the marshmallow at once. Others toyed with it. One tried to tear out a chunk that might go unnoticed. A few were able to hold off completely. The video of this experiment is available online, along with a number of similar studies, and is very funny.

What is amazing is the correlation between the ability to defer gratification at a young age and success later in life. The researchers followed up with the same kids later in life and found that those who could hold out for two marshmallows did better in high school, better on standardized tests, and better in college.

Which brings me back to central bankers…

It’s no secret that the Federal Reserve has kept U.S. interest rates low to encourage borrowing which, aside from student loans and car loans, has been slow to materialize. Maybe U.S. consumers can pass the marshmallow test while Fed bankers cannot.

Or, more likely, many consumers are in no position to borrow, and those that are qualified borrowers earned that status by avoiding a bunch of debt in the first place. Now, the European Central Bank (ECB) is getting in on the act.

The ECB recently began another loan program, whereby the central bank will lend to traditional banks at very low interest rates, hoping that those banks will in turn lend to private companies. The goal is to stimulate borrowing that would ostensibly be used to buy equipment, supplies or some other business input, which should lead to more economic activity and growth.

The ECB plans to push roughly one trillion euros into the euro-zone economy through such loans, but borrowers aren’t playing along.

Instead of rushing to take advantage of the program, many qualified businesses are refusing to borrow. Perhaps they remember just a few short years ago when troubled banks called many loans — whether businesses were current on their payments or not — because the banks needed the capital.

Saying No to a Loan

Business owners don’t want to be in that situation again. Maybe they don’t see enough demand to justify jumping into debt and are not interested in using the strategy of “build it, and they will come.” Whatever the reason, it appears that like most qualified U.S. consumers; qualified European business leaders can also pass the marshmallow test.

The most frustrating part of this is that central banks are in the debt (or marshmallow) business at all. I believe that central bankers are smart, well-read people who understand exactly what is going on. The problem is they have been given an impossible task — to make economies grow, no matter what.

The tools at their disposal, generally interest rates and money, mean that their plans will always revolve around cash and debt… they must.

So what do you do when the nation has binged on debt and spending, which would naturally be followed by a period of contraction, write-offs, and deflation? Let the cathartic but painful process unfold, or try to hold back the natural economic ebb and flow?

As central banks prove ineffective at turning the tide year after year, the more obvious the answer becomes.

October 7, 2014

The 3 R’s Spell Inequality

Can you afford to give your kids a higher education? Some of us can and for some, it’s just out of reach. Our research shows that we historically get stock and economic bubbles in the latter part of the fall season when technologies are moving mainstream. A generation is aging into its peak spending and productivity while simultaneously, inflation and interest rates are falling. All of these factors increase profits and speculation.

The growth companies that are moving mainstream create huge profits for entrepreneurs and growth managers. The bubble in stocks accrues heavily to the top 1% to 20% that own most financial securities outside of personal real estate.

In the fall bubble boom peaks of 1929 and now (since 2007 to today), the top 1% garner near 50% of the net worth and even higher for financial assets. But that can fall to as low as 26% in the late spring and summer seasons when new technologies become ubiquitous enough to raise the wages and net worth of the middle-class like they did in the fall boom for the upper class.

The demographic and technology trends peaked in late 2007. But in today’s unprecedented boom, the Fed and central banks around the world have pulled out all the stops to keep this bubble going and the end result is that the rich keep getting richer.

But there is another unique factor in today’s extreme inequality in incomes and net wealth where the top 1% garners over 20% of the income and the top 20% over 50%…

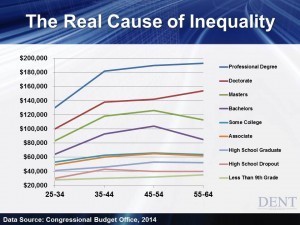

And that is education. Look at how much average income varies by age between high school dropouts at $40,000 and professional degrees (doctors, dentists, lawyers, accountants, etc.) at $193,000. That’s almost five times.

Big Bucks and Inflation

You have to make around $120,000 to be in the top 20% today. That’s primarily the people with the top three degrees from masters to professional. The top 1% at $450,000 would be the upper professional and include entrepreneurs, top executives, medical surgeons and specialists.

Note here that the highest degrees peak the latest, in the 55 to 64 range. Most, including master’s degrees, peak in the 45 to 54 age range. Our detailed research into spending by age suggests that the most affluent peak around age 53 and the everyday household at age 46. People who are more affluent generally go to school longer, and then their kids do so as well, extending their consumer spending cycle.

It obviously shouldn’t surprise you that higher education creates higher incomes. But the degree is what’s so important here. And there is an important trend driving that which most people aren’t as aware of: the unprecedented inflation in higher education.

Since 1983, education has experienced the highest rate of inflation of any other sector — much more than even health care.

Instead of subsidizing higher education, like in Europe, government policies have shifted away from that and have turned to encouraging student loans, wherein they actually make substantial profits.

The rate of inflation locks out all those kids who don’t already have rich parents. If these kids do get student loans, it weighs them down and reduces their ability to get married, buy a house and live well.

Virtual Education

For years, the U.S. has been an immigration magnet and an entrepreneurial country with high social mobility. That’s no longer the case. That changed dramatically with the explosion in education costs.

So what we need is a revolution in education. Everything about the Internet and this age of information points to the fact that this should and will happen. Why should the cost of education be ever increasing when it’s an information-intensive industry and the costs of information and communications are falling dramatically?

Teachers’ unions, tenure, the high costs of large campuses and rising student loans feed the inflation bubble. I fully expect education to shift toward more classes being taught online or streaming directly from the best experts in the world, not just the local professors.

There will still be interaction and live courses in many areas but campuses could be cut substantially and facilities leased out to the private sector or to research and development companies.

I cover this more in Chapter 9, pages 310 to 313 of The Demographic Cliff. As long as special interest groups fight this, and they will, that revolution won’t take place. It’ll only happen when our economy melts down and educational facilities no longer have parents and students by the jugular. The educational institutions will be forced to either change… or fail.

Then we could see the cost of education fall dramatically — after all, it’s the biggest of all the inflationary bubbles and the bigger the bubble, the bigger the burst. This and falling costs of health care and housing will give a shot in the arm to the growth of the middle class again and restore upward mobility, as occurred from the mid-1930s into the mid-1970s.

The wisdom of our governments and present leaders in education will not break this inequality paradigm. It’s the winter season that will make the change… and I welcome it.

Harry

October 6, 2014

Would You Pay Someone Forever?

On the face of it, pensions are stupid.

You pay someone a little bit each month over your working life, and then they pay you a little bit each month until you die. The difference is, you know how long you’ll work, but they don’t know how long you’ll live. The risk of dying soon after retirement and having the other person keep all the money is offset by the possibility of living a really long time, where the other person must keep on paying.

But there is a mitigating factor — the law of large numbers.

Any group offering a pension can’t know (without employing a hit man) exactly when any one person will die, but they can be uncannily accurate in knowing when the average person will die. As long as such entities offer pensions to enough people, then the numbers work out, matching up contributions charged with benefits paid.

With this one simple twist, societies suddenly have a way for the Average Joe to secure a stream of income for the rest of his natural life after work.

Unfortunately, this basic relationship has been co-opted by companies and governments for their own purposes, and has created a monster that’s taking over balance sheets and budgets. Companies have realized their mistake, while governments just keep charging ahead taking taxpayers with them…

There’s nothing inherently wrong with a company or government (city, state, federal, etc.) managing pensions, as long as they realize that the laws of math apply to them. The law of large numbers is easy to see; it’s not the problem. Trouble arises when these entities try to supercharge returns by branching out from the traditional holdings of pension funds — bonds.

Pensions as BenefitsThese boring fixed income investments pay known streams of income, interest and principal, at known times. Pension funds match up this income against their expected benefit payments as determined by contributions and the expectations of how long people will live.

But using bonds wasn’t good enough for most government or corporate pensions. They branched out, investing in equities and other securities.

Companies and governments promised pensions, either in full or in part, that employees wouldn’t have to pay for. This benefit was a recruiting and employee retention tool and was used in lieu of higher salaries. Of course, this meant that the company or government was on the hook for making the necessary contributions, which could be quite substantial.

In order to lower the contribution amount required, pension managers began investing in securities that, on average, had higher returns than bonds. With higher assumed returns, the contributions required by the company or government fell like a rock. It was magic!

Right up until it didn’t work.

Obviously stocks don’t have a preset return, so investors can make more than they can on bonds… they can also lose and there’s the rub. Once pension funds stray from holding very predictable long-term investments, there’s the real possibility that funds can come up short. Since the promise to employees still exists, the company or government must look elsewhere to make up the difference, either out of their own balance sheet or by charging taxpayers.

This situation was made worse as pension sponsors failed to make their required contributions, hoping that future equity gains would bail them out. Eventually, many plans fell below 100% funding, with some holding less than 50% of what is required to make good on all of their obligations.

The reality of the situation is not lost on the plan sponsors. Companies have been off-loading or unwinding their pension obligations for decades, attempting to move employees to 401(k)s if possible. Many cities, states, school districts and other government bodies that offer pensions have tried negotiating lower benefits and higher contributions from employees.

Their efforts are stymied by the fact that the blame for the current state of the pensions falls mostly with the sponsor itself.

The Unpopular SolutionGeneral Motors recently handed off its pension to an insurance company and Motorola is about to do the same thing. The insurance companies are expected to manage the funds in a more traditional way, matching up long-term streams of income with long-term liabilities (benefits). Since the pensions are managed by a third party, the companies can no longer fudge their contributions or expected returns.

Government entities could do the same thing — shift their pensions to true pension companies that use a conservative approach to investing. But the move isn’t free.

When a company takes over a pension like this, it has to be fully funded. If the pension is not fully funded, the pension sponsor remains on the hook for the balance. A current Moody’s report showed the 25 largest public pension funds are underfunded by $2 trillion.

Where in the world will government entities get the funds to make up such a large difference?

They’ll come to you and me… as taxpayers. This is the cost we all will bear for years of mismanagement that we failed to stop at the ballot box.

Rodney

October 3, 2014

Unretirement is Unrealistic for Boomers and the Next Generation

I was reading the paper recently when I happened upon a review of the book, Unretirement (Bloomsbury Press, 2014) by Chris Farrell. The premise of the book is that boomers have changed every stage of life they have passed through, and they are set to change retirement as well. No longer will workers rejoice when they reach age 65 and immediately hit the road to Florida.

Instead, the huge generation of boomers will look around and realize they are bored, healthy, well-educated and unable to afford traditional retirement. This will lead many if not most of them to seek out something — anything! — that they can do to provide meaning for their lives as well as income.

His suggestion — don’t wait. Plan today for your “unretirement,” the point in life where you can reinvent yourself, either full-time or part-time. In addition to keeping you active and involved with interpersonal relationships, still working in some capacity will provide substantially more financial benefits than any sort of savings or investment plan.

The reason is that while you work, you’re not drawing money from your savings and you’re marching closer to the day when you can draw 100% of your Social Security benefits. It’s a two-for-one great deal!

Farrell points out that more boomers are working during traditional retirement age today and the trend should only grow. In addition to benefiting the workers, this also bodes well for employers, who are watching decades of education and expense walk out the door.

But there’s another side to this story, and it starts with the same people — retirees and those nearing retirement…

It’s true that the percentage of people 65 and over in the workforce has increased in recent years, and the number has moved up from 12% in 1990 to 16% in 2010 and 18% today. That’s a big increase, but it still means that 82% of people 65 and over are not in the workforce. Even if another 10% of boomers stay on the job, the number would only reach 28%, with 72% kicking the time clock goodbye.

Farrell believes that roughly two-thirds of retirees will be able to make it on their savings, which seems odd. The 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances from the Federal Reserve shows the median net worth of people 65 to 74 is $232,000, including $88,000 of equity in their primary residence. It’s difficult to see how two-thirds of retirees will be just fine when the median person 65 to 74 years old has roughly just $145,000 outside of his home.

Keep in mind that this means half of everyone in that age group has less.

For Mr. Farrell, the real worry is about the one-third of retirees that have little savings and are counting on Social Security for the bulk of their retirement income. Given that the typical benefit today is $1,290 per month, it won’t go very far in covering housing, transportation, food, and medicine, much less travel and leisure.

But to say most everyone should and will simply work longer to alleviate this pressure glosses over a lot of facts. The people most able to continue working at their chosen pace are the same people who are already comfortable — top-level executives and entrepreneurs. The farther down the pay scale you go, the less likely an employee is to have any power to set his or her own schedule. The choice is to work, or not.

Then there is the whole question of what would happen if boomers did choose to stay in their jobs — or get new ones — en masse? Millions of job openings that would have been taken by gen-x’ers, which would make room for the emerging millennial generation to enter the workforce, would never become available. This would keep the young, emerging generation from getting a leg up on the corporate ladder, which would delay them even further in terms of ramping up their consumer spending.

Would we rather encourage boomers to stay in their jobs so that they can stash more cash and feel comfortable in retirement? Or make room for millennials to join the workforce in quality jobs so that they can go about getting married, having kids, and spending with abandon? The answer to the question is up for debate but in the end is probably moot.

While it might be much better for boomers to keep punching in for a few years after 65, most of them won’t do it. And of those that do, most are probably self-employed people that have the least financial need.

Rodney

October 2, 2014

Dow Jones Today Shows Warning Signs

The best analogy I’ve heard for bubbles and why they ultimately burst is the example of dropping grains of sand that build a mound. It gets steeper and steeper until one grain of sand causes an avalanche.

You can clearly see when the mound is getting steep, but no one knows when the final grain will set it all into motion. I’m seeing growing signs from several angles that an avalanche is about to occur.

Adam is heavily monitoring small-cap stocks as they continue to underperform the large caps as investors get more selective toward large caps at almost every major top — especially bubbles.

Take a look at Alibaba — the greatest IPO in history that buried Facebook’s performance of a few years ago. That event can be compared to the cities with accelerated growth constructing the tallest buildings in the world just as real estate and major economic tops occur…

The examples are many: the Empire State Building in 1930, the World Trade Towers in 1972, the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur in 1997 before the Southeast Asia crash, and now, the Freedom Tower in New York. The Shanghai Tower was just completed and of course, there’s the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Dow Jones Reflected in the MarketsMargin debt and speculation are at record highs, greater than in early 2000 or late 2007 when the last two bubbles peaked. The Dow Megaphone pattern with higher highs and lower lows is reaching its likely final E-wave peak around 17,300 as I’ve been forecasting for the past two years. Markets can continue to edge up, but with likely very little gains unless they break decisively above this upper trend line. This very ominous pattern makes me think that it’s not likely.

The Dow went up 33% from late 2012 into the end of 2013, in just 13.5 months. But this year, the Dow is only up 4.2% in nine months. This is another warning and vindication of the megaphone pattern thus far.

I wrote an article last week about massive denial from economists and analysts alike; who come on one after another and declare this isn’t a bubble because… stocks aren’t that overvalued compared to past major peaks.

Okay, here’s my question — what major peaks? We’re at levels that compare with most major peaks in history in price-to-earnings ratios (P/E). Robert Shiller has the better indicator and it takes the cyclicality out of the earnings and shows that we’re above peaks dating back to 1902 and all the way up to 1987. We’re closest to 2007’s peak. Only the extreme bubbles with the best demographic and geopolitical cycles in 1929 and early 2000 are higher.

But you can’t compare today with the massive geopolitical risks and rapidly declining demographic trends with 1929 or 2000 when such trends were the most positive!

Buying power has been sluggish as occurs in major tops as measured by Lowry’s and selling pressure is starting to rise, but there’s a huge factor missing so far… an accelerated rise in selling pressure.

I think that is due to investors coming to the ominous conclusion that the Fed just won’t allow the economy or markets to go down much. In other words, have no fear.

That’s definitely not a good sign!

No fear is another major sign of overvaluation, but then when the first sign appears of something going wrong, it creates a major shock and reality reset. Our demographic and geopolitical indicators strongly suggest things are going to go wrong ahead — as do our boom/bust sunspot cycles turning down in 2014 for the first time since early 2000.

Add to this scenario that economists and analysts continue to cite the rises in earnings, GDP and jobs growth as the reasons that the economy is doing fine and there won’t be a recession or downturn ahead. I’m listening to Jeremy Siegel as I write this and his view is that stocks are not overvalued and will continue to go up for years as there is no recession in sight. I would ask if a recession was insight when stocks topped in early October 2007?

I love academics and Siegel is loveable… but don’t listen to him.

Good trends always occur into major tops. How did Japan look in late 1989? How did the U.S. look in late 1929 or early 2000 or even in late 2007, for that matter? The good trends don’t necessarily mean a downturn or crash is imminent… but looking back at history, they’re clearly not a reason to say that a downturn can’t happen.

You’ll rarely see major tops by looking at short-term economic indicators.

Normally the smart money is the first sign that a major top is happening as they sell into tops and buy into bottoms. There are initial signs of that with buying power waning and small caps underperforming, but not as clear as in past tops.

More affluent households who are larger investors have the same affliction as the smart money — no fear due to faith in the Fed and artificially rising markets that have made them richer than ever.

I think that most Homer Simpsons may be better off than the smart money here — as they don’t see a real recovery in the first place.

That’s why selling pressure is not as high as it could be here in the final stages of this great bubble. This could be the secret indicator that does not flash as clear or bright a sell signal. Even the smart money tends to miss it at first. We’ll see.

So, we advise you to sell stocks on every rally in the weeks and months ahead in your 401(k) and passive investment models. For those following Adam O’Dell’s active strategies in Boom & Bust and Cycle 9 Alert, stick to his game plan. He’ll make tactical adjustments as they become necessary and he is increasingly on alert.

We don’t know when that final grain of sand will drop — but it’ll create an avalanche when it does drop. Bubbles don’t correct, they crash!

We continue to advise that it’s better to get out a bit early than too late. I still see very little upside from here and a huge downside of a possible 65% drop on this Megaphone Pattern.

Be warned and have the courage to act decisively… protect your assets!

Harry

Follow me on Twitter @harrydentjr

October 1, 2014

Understanding FedSpeak About Bonds

After the last meeting of the Federal Reserve, Chair Janet Yellen announced that the committee voted to lower its bond buying from $25 billion to $15 billion per month, and then cease bond buying altogether after October.

Depending on how you look at it, this brings an end to a program that has either been hailed as a great success or reviled as the biggest theft in American history. But either way, most people have come to the logical conclusion that if the Fed’s no longer buying bonds, then interest rates will naturally rise.

The problem is… it’s not true. The Fed’s purchasing of bonds is far from over.

The statement by Chair Yellen about the end of bond buying applied to the committee’s latest attempt to turn the economic tide by forcing down long-term interest rates through a program of printing new dollars to buy medium and long-term bonds. This program known as Quantitative Easing 3 (QE3) has been part of our lives since December of 2012.

In the intervening months, the Fed has purchased well over one trillion dollars’ worth of bonds and clearly held down interest rates from what the market would’ve been.

In December of last year, the Fed announced plans to reduce the rate of its bond purchases under QE3 at each successive meeting with one specific goal in mind…

Ending the purchase of bonds entirely by October of this year.

It’s true that the Fed will stop adding to its bond portfolio in October but there’s the pesky issue of managing the roughly $4.2 trillion worth of bonds that the Federal Reserve now owns. These bonds have varied maturity dates so it’s fair to ask what the Fed intends to do as bonds pay off. Luckily, Chair Yellen addressed that issue specifically.

In her statement after the last meeting, she said that the size of the Fed’s portfolio will remain intact at least until short-term rates begin to move higher, which she’d already stated would happen a “considerable time” after the end of QE3.

So bond buying, intended to increase the Fed’s holdings, will end in October and then short-term interest rates will remain near zero for a considerable time, which many analysts expect to be at least six to nine months.

The size of the Fed’s portfolio won’t drop before this, which means that the Fed must reinvest the proceeds when any of its current holdings mature or pay off early.

Early payoffs and maturing bonds can represent a substantial sum of money when you own $4.2 trillion dollars’ worth of securities.

The Fed’s recent report on holdings shows $1.1 trillion worth of bonds maturing in one to five years with a smattering of holdings that mature over the next several months. As to how many bonds will be called before they mature, that’s anyone’s guess.

For investors expecting to cash in on rising interest rates because the Fed’s about to be “out of the market,” they might have to wait a bit longer than October. And since growth rates in large, developed nations around the world keep disappointing, there might not be many other factors that will push rates higher in the near term.

Rodney

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

September 30, 2014

Why Netflix is Your New Best Friend

To say that I like routine is an understatement. My lovely wife often says I’d eat the same meal every night and be happy. While that’s close to true, I’m quick to point out that I’m also thrilled to come home to the same woman every night… predictability has its advantages.

Apparently this isn’t the case in the world of marketing, where the goal is to reach people who are presumably more likely to try something new and are open to switching brands.

Recently, the A&E cable channel canceled the program “Longmire.” The show ran for three years and was based on the crime mystery books by Craig Johnson. The protagonist is Sheriff Walt Longmire, a brooding man short on words but long on character traits such as honesty and perseverance. The show was so popular that it became the second highest-rated program for A&E, behind “Duck Dynasty.”

The problem is that the show is a hit with the wrong crowd…

The average age of viewer for “Longmire” is 60, well outside of the 25- to 54-year-old demographic sought by many advertisers, and light years away from the hip 18- to 49-year-old group. This put “Longmire,” as a product, into a bind. The show had a very high following (5.6 million viewers), but it didn’t draw advertising dollars. A 30-second ad during “Longmire” cost roughly $31,300, while a commercial during “Mad Men,” with less than half the viewers at 2.5 million, cost more than twice as much, $69,500.

The difference is that “Mad Men” attracts 1.4 million 18- to 49-year-olds and 1.7 million 25- to 54-year-olds, while “Longmire” pulls only half as many in each age group. Marketers love these age groups because they are populated with people who are open to receiving the advertising message — “buy our stuff.” Apparently, as we move closer to 60, we get set in our ways.

I must have peaked early. As I said, I like a routine… and I happen to like “Longmire” as well.

But there is a solution for “Longmire” fans; watch programs On Demand. This is the entire premise of Netflix. The streaming video website has spread like wildfire by offering not only movies, but also entire seasons of famous and even not-so-famous television shows.

By using Netflix, viewers can “binge” watch programs, consuming entire seasons in a couple of days, which crams together cliffhangers from one week and resolutions from the next. When popular programs like “Longmire” get kicked to the curb because they don’t draw enough advertising dollars, it’s a sure bet they will pop up on a video streaming service where the goal is to drive membership dollars. Simply sign up and watch all you want.

For the average 60-year-old, plus a few of us who are younger but happen to like some of the same programming, Netflix could become a new best friend.

Think about this group for a minute. Sixty-year-olds were born almost a decade after WWII. They’re smack dab in the middle of the boomer generation, and changed every part of life as they aged. While they might not be the best audience for the typical television advertiser, they’re still an exceptionally large, and therefore powerful, generation.

In an effort to generate more ad dollars, A&E might be shooting themselves in the foot by pushing an influential group off of cable television. In their search to find the programming they want, these boomers might find a lot of other content they like, and realize they neither need, nor want, cable TV… at all.

I wonder how many television ads can be sold when no one is watching.

Rodney

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent

Follow me on Twitter @RJHSDent