Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 10

November 15, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 15, 1882

11/15/1882: Justice Felix Frankfurter's birthday.

Justice Felix Frankfurter

Justice Felix FrankfurterThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 15, 1882 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 14, 2025

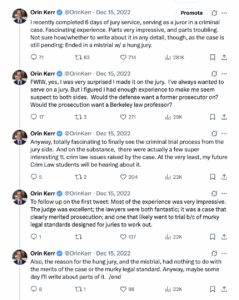

[Orin S. Kerr] My Experience as a Law Professor Juror

[I did it, and I recommend it.]

I thought I would flag in response to Josh's post that I served on a criminal jury three years ago—and that, unlike Josh, I recommend that other law professors do the same. I tweeted a bit about it shortly after my jury service:

In his post, Josh suggests that law professors might have trouble being good jurors:

The role of the jury is to find facts, not law. Law professors are professionals at conveying the law. I would like to think that I would follow the law exactly as the judge instructed me--indeed, I told the judge I would during voir dire. But I think it would be hard to entirely set aside my views on what the law is.

I didn't find that hard at all. In addition to be an officer of the court as a bar member, I swore an oath as a juror to render a "true verdict . . . according only to the evidence presented to [me] and to the instructions of the court." I took that oath with utmost seriousness. It didn't occur to me to violate my sworn oath out of some personal sense of what the law should be.

Josh also suggests that other jurors will be unable to think independently after hearing the views of a law professor:

The bigger problem is that other members of the jury pool would look to the law professor to explain the law. And even if I resisted offering any statement of the law, my view would be given undue deference.

That wasn't my experience. In my case, the other jurors knew from the open court voir dire that I taught criminal law and procedure at U.C. Berkeley (where I was teaching at the time). They knew that I was a former prosecutor who did occasional criminal defense work, too. And the case we had was in my area: Not only was it a criminal case, but it was a case involving offenses that I teach—although I teach the Model Penal Code version rather than the California Penal Code.

Nonetheless, the other jurors were independent and made their own judgment calls. I like to think that I made some good arguments about the evidence, and whether the government had proved particular elements of particular offenses beyond a reasonable doubt. (I thought they had proved some offenses but failed to satisfy their burden of proving other offenses.) But I was just one of the twelve jurors, and everyone had their own take on things. I intentionally took a light touch and tried to avoid saying too much. I explained a particularly confusing jury instruction once, and I tried to focus the discussion on the elements of the crime and the evidence. But no one was giving undue deference to me, at least as far as I could tell.

Anyway, maybe I'll write more about my time on the jury some day, as it was a fascinating experience.

The post My Experience as a Law Professor Juror appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal

[Firework permits, intratribal smokes, and really just a whole lot of shootings and killings.]

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

In 2023, police in Marion, Kan.—armed with bogus warrants—raided the offices of a local newspaper, the home of the newspaper owner (a nonagenarian who died of a heart attack the following day), and the home of a city councilwoman who'd been critical of the mayor. And this week, Marion County and its sheriff agreed to a financial settlement, admitted the raids violated the First and Fourth Amendments, and apologized. The lawsuit proceeds, however, against the City of Marion and its now-former mayor and now-former police chief. Read all about it in the Marion County Record, or The New York Times, or quite a few other places.

Over at The Wall Street Journal, meanwhile, IJ's Anya Bidwell and Patrick Jaicomo call a spade a spade and say that this week's vote in the Senate to give senators—and only senators—a cause of action to sue federal officials (who, notably, are also stripped of qualified immunity) is an unqualified betrayal.

New on the Short Circuit podcast: TikTok star and real-life lawyer Reb Masel tells us a tale about how a moonshine argument led to years of jail without trial.

After Springfield, Mass. woman is arrested for disorderly conduct, she does three months of pre-trial probation without admitting any wrongdoing, and the charges are dismissed. She sues the arresting officers for excessive force. District court: Heck bar doesn't apply because it only prevents lawsuits that would impugn a conviction, and here there was none. Officers: That's an "excessively literal reading" of Heck. First Circuit: OK, but figuratively speaking, you're trying to stretch Heck way beyond its bounds. Affirmed. (Literally the result IJ urged.)New York makes it illegal to sell dietary supplements to minors if those supplements are marketed as aids in weight loss or muscle building. Supplement sellers: That sounds an awful lot like a restriction on speech! Second Circuit: Sure does, but it also sounds a lot like a restriction that survives Central Hudson. Preliminary injunction denied.Fourth Circuit: Just so we're all on the same page, law enforcement officers do not have carte blanche to pull guns on people whenever (in the words of this Richmond, Va. officer) "there's any type of crime that's committed, regardless of what type of crime it is."A problem that complicates Biblical studies is different texts written by different authors at different times. For example, some scholars argue that Mark and the "Q" source date to the 40s or 50s (AD) while Revelations came decades later. Similar challenges stack up against a repeat drug trafficker, who argues he is eligible for First Step Act relief because he is serving "a sentence" for a qualifying crime while also, unfortunately for him, serving "a sentence" of a disqualifying crime. Part of his argument rests on a comparison with the Second Chance Act. Fourth Circuit: "[T]he original text of the Second Chance Act was drafted at a different time—in 2007—by a different Congress with different considerations in mind." Habeas denied. Dissent: "Can a prisoner 'serve' a 24-month sentence for 144 months? Of course not."After Columbus, Ohio police kill an unarmed man in bed during an early-morning raid, his survivors sue the department alleging a custom of racially discriminatory policing and excessive force. The suit claims, in part, that the collective bargaining agreement for police shields bad apples, and it seeks to overturn some of its terms. Sixth Circuit: And in such circumstances, the police union must be allowed to intervene to defend the agreement. (Your summarist wonders whether the court's acknowledgment that the city's elected gov't has conflicting interests with the union in defending the lawsuit has any broader implications about public-sector unions.)Connoisseurs of local-gov't meetings will like the part of this Sixth Circuit case in which a citizen objects to his neighbor's proposal to host an Orthodox Jewish prayer group on the Sabbath (a day on which their religion forbids them to drive) on the grounds that it would cause "parking issues in the area." Connoisseurs of ripeness rules will like the part where the neighbor loses anyway because city officials never decided whether having some friends over to pray required a permit in the first place.Benton, Ark. officer shoots, kills teen who was holding a gun to his own head as the teen allegedly—question for the jury—attempted to comply with the officer's order to drop the gun. Jury: We don't think this one's on the officer. But the city and the police chief are liable for failing to train him properly and failing to investigate prior accusations of excessive force against him. Eighth Circuit: Look, no one told the jury this, but you can't have a verdict like this. No constitutional violation by the officer = no liability for the city or the chief (absent conditions that are not met here). Please consult this appendix containing 51 circuit opinions dating back to 1986 that say so.Environmentalists: It is very, very important that embers from a Long Beach, Calif. restaurant's annual July 4th fireworks display do not land in Alamitos Bay without a permit. Ninth Circuit: Whelp, now they have a permit. And we have all the fireworks puns.Indian tribe makes cigarettes on its remote northern California reservation that are only sold on tribal land (including other tribes' land). California: And we're going to need you to pay state taxes on those. Ninth Circuit: Neither tribal sovereign immunity nor qualified immunity protects the tribe or its officials from the state's suit.After shooting three people (two of them fatally), mentally ill man takes 12-year-old boy hostage. Henderson, Nev. police arrive, and a sergeant tells officers to "[t]ake the shot if you have it." An officer fires a single round, killing the man. But then other officers open fire two seconds later and kill the boy. Ninth Circuit: Qualified immunity.In lieu of a citation for allowing her dogs to roam off leash, woman consents to Locust Grove, Okla. police taking them. An officer shoots them, but one survives and finds its way back home nine days later with a bullet hole in its head. Tenth Circuit (unpublished): Your complaint didn't satisfactorily allege that you expected to be able to get the dogs back, and it doesn't help you that the officers may not have followed the relevant animal-control procedures. Case dismissed.Remember when 60,000 Americans voted for Kanye for president? A marketing company provided services for his campaign under a handshake agreement between the company and a political consultant working for Kanye. Yikes! The marketing company was allegedly never paid for its work. Tenth Circuit: But it can't sue Kanye's campaign directly, as there's not an inkling of support that the campaign agreed to hire the company, as opposed to the consultant. (Fear not: the marketer's suit against the consultant continues.)Pregnant woman at Florida airport requests pat-down rather than X-ray screening out of concern for her unborn child. Prolonged probing of her vaginal area reveals something in her underwear, which she explains is toilet paper to stem bleeding related to the pregnancy. TSA agents are unconvinced, take her to a separate room, and strip search her (it is toilet paper). She sues. Feds: TSA agents are immune from suit. Eleventh Circuit: We join five of our sister circuits in holding that is incorrect.Seems weird that a thorough, 50-page opinion with a dissent would be unpublished, but what do we know. In related news, this Florida prisoner who was denied care for chronic pain caused by a prison bus accident—pain that was exacerbated by further injuries in his prison workplace—loses his appeal at the Eleventh Circuit.In the wake of the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, victims filed 60 lawsuits against the Sheriff of Broward County, alleging negligent failure to secure the school once the shooting started. The Sheriff's office has insurance that kicks in after the Sheriff pays $500k plus a $500k deductible "per occurrence." The insurer argues that the shooting was not one occurrence, but instead dozens of occurrences, one for each bullet. Eleventh Circuit: Incorrect.In 2019, an officer in the Royal Saudi Air Force opened fire at Pensacola Naval Air Station, killing three servicemen and seriously injuring 13 other people. The survivors and the victims' families sue the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Eleventh Circuit: And considering how open the shooter was on social media about his radical beliefs, the district court should not have dismissed the plaintiffs' claim that Saudi Arabia was grossly negligent in hiring and vetting the shooter.New case! New York City is in the grip of a housing crisis, and yet at least 25,000 apartments sit vacant, withheld from the rental market. What gives? Dumb laws. The city requires landlords to perform extensive maintenance and upgrades to keep older units up to snuff, but at the same time forbids the rent increases that would make that economically feasible. Who's going to spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars on upkeep when they're only allowed to charge $700/month in rent? It's bananas. And because the rent caps are tethered to each unit's individual rental history, similar apartments are capped at arbitrary, wildly disparate, and generally far-below-market rates. So this week, brothers Pashko and Tony Lulgjuraj, who worked for decades in building maintenance and eventually purchased a building of their own, filed suit challenging the city's rent-stabilization regime for vacant apartments. Click here to learn more. Or head over to The Wall Street Journal for their editorial board's take.

The post Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] A Law Professor On A Jury?

[A challenge for cause or a peremptory strike?]

This week, I was called for jury service. And, like in past years, I was dismissed. I think as a general matter, it is not a good idea for a lawyer to serve on a jury. Perhaps in a place like Washington, D.C., where a substantial percentage of the population is an attorney, such service is unavoidable. But at least in Houston, I was the only lawyer on the panel of fifty.

I think it is an even worse idea for a law professor to serve on a jury. The role of the jury is to find facts, not law. Law professors are professionals at conveying the law. I would like to think that I would follow the law exactly as the judge instructed me--indeed, I told the judge I would during voir dire. But I think it would be hard to entirely set aside my views on what the law is.

The bigger problem is that other members of the jury pool would look to the law professor to explain the law. And even if I resisted offering any statement of the law, my view would be given undue deference. For example, several years ago, I was called for jury duty in a criminal case. During voir dire, the defense counsel said "Professor Blackman, what does the Fifth Amendment say?" I immediately realized how fraught that question was. The jury would immediately look to me to answer legal questions. I replied, somewhat evasively, "Which Clause?" I suppose he could have been asking about the Takings Clause? He replied, "Self incrimination" and moved on. This week on jury duty, counsel for the plaintiff revealed that he was one of my students. Again, the jurors would now look to me to judge whether my former student was correct. During a sidebar at voir dire, I told the judge, and both counsel, about my concern that the other jurors would look to me to determine the law.

For good reason, I was excused from jury service. I do not know if either lawyer used a peremptory challenge, or challenged me for cause. Is being a law professor per se grounds for a strike? I don't know.

I welcome emails from any other law professors who have been selected for a jury.

The post A Law Professor On A Jury? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Sasha Volokh] My Esperanto Film, "Nova Espero" ("A New Hope"), Needs Your Likes!

[Please vote on my submission to the Esperanto film festival.]

Just a reminder to click through to YouTube and hit "like" on my new short Esperanto film, "Nova Espero," or "A New Hope," which I've submitted to an Esperanto film festival (the 7th American Good Film Festival). (When I say "short," I mean it's under five minutes long. Hit CC if you don't see the English subtitles.)

I'm embedding the film below, but most importantly, please click through to YouTube and "like" ("thumbs-up") the video there: "audience favorite" gets a special prize in this film festival! Voting only lasts a few more days, so please do it now.

The post My Esperanto Film, "Nova Espero" ("A New Hope"), Needs Your Likes! appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Again with the Heckler's Veto in a Government Employee Speech Case

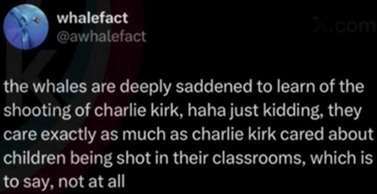

Brown, who worked at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission reposted this item from an Instagram account that "posts satirical social commentary from the perspective of a whale":

This was apparently a reference to Kirk's comments that part of the price of the Second Amendment is that there would be "some gun deaths":

[At an event] held days after three children and three adults were killed in a school shooting in Nashville … Kirk [was] asked by an audience member how to make the point that protecting the Second Amendment is important. Kirk responded that the amendment "is there, God forbid, so that you can defend yourself against a tyrannical government." But "having an armed citizenry comes with a price, and that is part of liberty," he said.

"You will never live in a society when you have an armed citizenry and you won't have a single gun death," Kirk later said. "That is nonsense. It's drivel. But I am — I think it's worth it. I think it's worth to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment to protect our other God-given rights. That is a prudent deal. It is rational. Nobody talks like this. They live in a complete alternate universe."

(This is of course similar to the arguments that rights supporters routinely make when other rights lead to some amount of foreseeable deaths—the Fourth Amendment, the privilege against self-incrimination, the right to bail in many case, and so on. Characterizing it as "not caring at all" about the deaths strikes me as a poor argument, but that's a separate matter.)

This post became broadly seen (through the "Libs of TikTok" account) and led to lots of criticism, including criticism sent to plaintiff's employer, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which fired her. Plaintiff sued, seeking a preliminary injunction ordering her reinstatement. Judge Mark Walker's decision yesterday in Brown v. Young (N.D. Fla.) denied that preliminary injunction.

Generally speaking, a government employee's speech is protected against employer retaliation if (1) it's said in the employee's capacity as a citizen and not as part of the employee's job, (2) the speech involves "a matter of public concern," and (3) the speaker's "free speech interests outweighed [the employer's] interest in effective and efficient fulfillment of its responsibilities." (This third element is often called the Pickering balance, after the case in which it was articulated.)

The court correctly concluded that the first two elements were satisfied, and that "it's not a close call":

First, it is no answer that Plaintiff's Instagram post, itself, is not original content. Courts have long recognized that re-posting memes or other content from other creators, without further comment, is akin to one's own speech.

Nor can Defendants immunize themselves by recharacterizing Plaintiff's speech as mere "association" with another's speech. Plaintiff spoke when she re-posted the third-party's speech as her own on her Instagram story. Full stop.

Likewise, there is no contention that Plaintiff's Instagram story amounts to unprotected government speech that owed its existence to her job at FWC or was even remotely related to the work she performed … [which was] monitoring imperiled shorebirds and seabirds ….

Defendants also contend that Plaintiff's Instagram story did not touch on a matter of public concern because it conveyed only "personal disdain" and did not contain any "civic commentary." … [But a] public employee's negative opinion about a public figure who has nothing to do with their job is generally not the sort of speech touching on a "personal interest" that garners no protection under the Pickering framework. [See, e.g.,] Rankin v. McPherson (1987) (holding that employee was speaking on a matter of public concern when she told a coworker that if another attempt was made on the president's life, she "hope[s] they get him") ….

It is also no answer that Plaintiff's speech was arguably satirical, sarcastic, or insensitive. "Humor, satire, and even personal invective can make a point about a matter of public concern." Indeed, "[t]he inappropriate or controversial character of a statement is irrelevant to the question whether it deals with a matter of public concern." Rankin.

But the court held that plaintiff hadn't [sufficiently clearly] met her burden "to show that her free speech interest outweighs FWC's interest in the effective and efficient fulfillment of its responsibilities":

Defendant Tucker['s unrebutted declaration] provides evidence that there was a swift and largely negative reaction from the public concerning Plaintiff's Instagram story which "disrupted agency operations, required diversion of staff resources to manage responses, and raised legitimate concerns about the agency's credibility and public trust." While Plaintiff understandably argues that this declaration is short on specifics and largely conclusory, Plaintiff also chose not to seek expedited discovery to depose Defendant Tucker or cross-examine her at the hearing to explore flaws in Defendants' position.

Without more, this Court cannot conclude on this sparse record that the public's negative reaction was not disruptive enough to justify the action FWC took…. "The government's legitimate interest in avoiding disruption does not require proof of actual disruption. Reasonable possibility of adverse harm is all that is required." …

It's still possible that, after further discovery, and perhaps after a trial, plaintiff will be able to show that the public reaction was less disruptive than the government says it was, and that plaintiff's "free speech interests outweighed" the disruption (however such weighing is to be done).

But the basic principle still remains: Under government-as-employer doctrine as it's currently understood, speech is protected only until it draws enough public condemnation. Once the speech (whether left-wing, right-wing, or any other) is publicized enough that enough people complain to the employer, the Pickering balance comes out in favor of allowing the firing.

I discussed this in a post about the subject right after the Kirk murder. As I noted, if one looks at court cases over the last several decades, they have routinely turned on whether the speech created enough public controversy. When the government is administering the criminal law or civil liability, such a "heckler's veto" is generally not allowed: The government generally can't shut down a speaker, for instance, because his listeners are getting offended or even threatening violence because they're offended. But in the employment context, the Pickering balance often allows government to fire employees because their speech sufficiently offends coworkers or members of the public. (The analysis may differ for public university professors, though it's not clear how much; see this post for more.)

This conclusion by lower courts applying Pickering might, I think, stem from the judgment that employees are hired to do a particular job cost-effectively for the government: If their speech so offends others (especially clients or coworkers) that keeping the employees on means more cost for the government than benefit, the government needn't continue to pay them for what has proved to be a bad bargain. Maybe that's mistaken. Maybe it's so important to protect public debate, including on highly controversial matters, that public employers should have to keep on even the most controversial employees (see this article by Prof. Randy Kozel, which so suggests in part). But that appears to be the rule.

We see this, for instance, with statements that are allegedly racist, sexist, antigay, antitrans, etc.: If they cause enough public hostility, or seem highly likely to do so, then courts will often allow employees to be fired based on them. But if they largely pass unnoticed except by management and perhaps just a few people who file complaints, then courts are much more likely to hold that the firings may violate the First Amendment (see, e.g., this post and this post, though there are many other such examples).

There are other factors that courts consider, to be sure: For instance, if the employer can show that a person's speech shows they are unsuited to the job, that makes it easier for the employer to prevail. But even there the magnitude of public reaction is relevant, because one common argument is that one trait required for certain employees is the ability and willingness to instill confidence and respect in coworkers and clients, rather than to produce outrage and hostility.

This creates an unfortunate incentive: Like any heckler's-veto-like rule, it rewards would-be cancellers, if they only speak out often enough and with enough outrage. But rightly or wrongly, that is how these cases generally shape up.

The post Again with the Heckler's Veto in a Government Employee Speech Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Our Amicus Brief in W.M.M. v. Trump - En Banc Fifth Circuit Alien Enemies Act Case

[I coauthored the brief on behalf of the the Cato Institute, the Brennan Center for Justice, legal scholars Geoffrey Corn and John Dehn, and myself.]

Yesterday, we filed our amicus brief in W.M.M. v. Trump, an Alien Enemies Act case currently before the en banc Fifth Circuit. I coauthored the brief, submitted on on behalf of the the Cato Institute, the Brennan Center for Justice (NYU), legal scholars Geoffrey Corn and John Dehn, and myself. Geoffrey Corn and John Dehn are leading academic experts on national security law, and former Army officers and military lawyers. Prof. Corn was formerly the Army's senior legal adviser on the law of war.

The brief builds on our earlier amicus brief in the same case, filed before a three-judge Fifth Circuit panel, which ruled against the Trump Administration. It argues that the it is illegal to use the Alien Enemies Act - which can only be invoked in the event of a war, invasion, or predatory incursion, or threat thereof - as a tool for peacetime deportation. Illegal migration and drug smuggling do not qualify as an "invasion" or "predatory incursion"; these terms refer to military attacks on US territory. And courts should not defer to administration claims that an invasion has occurred, when it very obviously has not.

If courts endorse the broad definition of "invasion" advocated by the administration, dire consequences will follow. Border states would be able to engage in war against neighboring nations even without congressional authorization, and the federal government could suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain people (including U.S. citizens) at will.

Parts of the brief draw on my new article, "Immigration is Not Invasion," which analyzes the meaning of "invasion" under the Constitution and the Alien Enemies Act, in greater detail.

The post Our Amicus Brief in W.M.M. v. Trump - En Banc Fifth Circuit Alien Enemies Act Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Bernstein] Why I Am Resigning from the Heritage Foundation (Guest-Post by Adam Mossoff)

[DB: This is a guest post from my Scalia Law colleague Professor Adam Mossoff, reprinting his letter to Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts resigning his position as a visiting fellow at the Foundation. As Adam says, this is a time for choosing on the political right: you either abandon conservatism and stand with Tucker Carlson and nihilism, collectivism, Nazism, and Jew hatred, or you stick up for (conserve, if you will) the American traditions of individual rights, religious and ethnic pluralism, and the rule of law.]

Dear Dr. Roberts,

It is with a heavy heart that I am resigning my Visiting Fellow position in the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at the Heritage Foundation. My resignation is effective immediately.

Please know that I did not come to this decision lightly, as it has been truly an honor to work for John Malcolm in the Meese Center for the past six years. John represents the best of Heritage, and he has inspired me. I have been tremendously proud of my legal memoranda on intellectual property law and innovation policy, and of the Intellectual Property Working Group that has been my charge. I am even more proud of my chapter on the Copyright and Patent Clause in the new edition of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, an impressive monograph representing the fruits of a multi-year productive effort by John and his co-editor, Josh Blackmun.

Unfortunately, your October 30 video, and your subsequent interviews, videos, and commentary, have made it clear to me that Heritage is no longer the storied think tank that I was proud to join in 2019.

I waited two weeks to send my resignation notice because I did not wish to act in haste, and I wanted my decision to be the result of a considered judgment, not a reaction based on the passions of the moment. Thus, I have been following closely the follow-on commentary and discussions by you and others, both externally and internally. From these observations, I have concluded that your October 30 video, as confirmed by your subsequent comments, interviews, and meetings, was not a mere mistake; rather, it reflects a fundamental ethical lapse and failure of moral leadership that has irrevocably damaged the well-deserved reputation of Heritage as "the intellectual backbone of the conservative movement" (your words in your October 30 video).

Your October 30 video was indefensible. So were your purported explanations and backtracking in subsequent interviews and social media posts. The October 30 video was worse than a poor choice of words or a mere mistake; it was a profound moral inversion to use the language of ancient antisemitic blood libels, such as "globalist class" and "venomous coalition." It was especially loathsome to use this same language to defend Tucker Carlson.

Tucker is quickly following Candace Owens down the very dark path of Jewish conspiracy theories and defenses of Nazis. (After Candace's "explanation" a couple years ago of Kristallnacht as a burning of communist books and not an attack on Jews, this was the final straw for me and my judgment has been repeatedly confirmed by her in the ensuing years.) Similar to Candace's "just asking questions" strategy, Tucker is increasingly hosting friendly, head-nodding-in-agreement interviews with people who explicitly praise Nazis and are unrepentant in their antisemitic slurs of Jews and Israel, such as his interviews of Darryl Cooper and Agapia Stephanopoulos. Tucker's friendly, smiling interview with Nick Fuentes, an avowed Nazi, was simply the nadir of Tucker's increasing number of friendly interviews with nihilists and antisemites.

In all of these interviews, Tucker has blatantly refused to challenge any of their calumnies, propaganda, and falsehoods, despite your subsequent claim in a follow-on X statement on October 31 that we should "challenge them head on" in open debate. This bears emphasizing: Tucker has never challenged one of these evil guests on his show. For example, in a two-hour interview with Fuentes, Tucker never asked Fuentes a single question about his Nazi views or even his Nazi slur of Vice President JD Vance as a "race traitor" given Vice President Vance's marriage to Usha and their "brown" children (to quote Fuentes). This is neither debate nor critical engagement with ideas with which we profoundly disagree. This is toleration of or agreement with evil ideologies and ideas. This is made even more clear by Tucker's contrary treatment of anyone he deems to be a "zionist." Unlike his interviews of Fuentes, Cooper, Stephanopoulos, and many others, Tucker engages in skeptical interviews with pointed, hard-hitting questions of Senator Ted Cruz and others about their "zionist" or "pro-Israel" positions.

All of this makes it absolutely clear that Tucker gives credence to his millions of viewers that evil ideologies — collectivism, nihilism, and antisemitism — are consistent with conservativism and the America First movement. Tucker's friendly and laughing conversation with Fuentes signals to his millions of young viewers that it is permissible to give a pass to such evil. Even in the best light possible, Tucker makes clear we at least should tolerate such evil, because, as you said in your October 30 video, we should not be "attacking our friends on the right."

This is a massive moral inversion. This is the opposite of what the Heritage Foundation has consistently stood for over many decades in American political discourse: the ideals of the Founding Fathers in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, our inalienable natural rights, limited government, the rule of law — and the free markets and flourishing society that results from these ethical and political commitments. This is the eminent think tank I first joined.

Although you told us in the townhall last Thursday that you made a mistake in your October 30 video, you have not retracted or withdrawn the video. It remains on your X account with more than 24 million views to date. Thus, it remains unclear precisely and specifically what you regard as your moral mistake and failure in leadership. This is compounded by the mixed messages you have been giving to us and to the world about the lesson you have learned. You have continually reiterated, for example, your claims in your October 30 video that we should not "cancel" our "friends," and that Tucker "always will be a close friend of the Heritage Foundation." As far as I'm aware, you have not disavowed this claim. But you falsely conflate here the struggle sessions and cancelation campaigns that the woke left inflict on their apostates and heretics with the proper and steadfast moral condemnation of nihilism, collectivism, Nazism, and Jew hatred.

Aristotle observed in his seminal treatise on ethics that, in a choice between truth and friendship, it is to truth that we must always give our primary allegiance. Even with your mixed messages, one thing is clear: By your words and actions, Heritage is wedded to Tucker and everything he has come to represent on the periphery of the Groyper movement created by Fuentes. Instead of the truth, you have chosen a false friend of the American ideals that Heritage has represented.

In the abstract, this profound failing of truth and justice would give me serious pause and I would still ultimately resign, but it's even more pressing today to call out this moral failing and to take a stand. It is still shocking to me that the worst single-day slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust, the invasion and attack of Israel on October 7, 2023, has unleashed a tsunami of violent antisemitism that has swept Europe and the U.S. In the past two years, woke Brownshirts have been screaming genocidal slogans in the streets and on university campuses (including my own university). They have been doing much worse than merely screaming slogans like "Free Palestine!" and "From the River to the Sea!"; they've acted in harassing and assaulting American Jews, firebombing and vandalizing homes and business, and murdering American Jews in DC, Colorado, and California. This has never before happened in the U.S.

This nihilism and collectivist bigotry has driven woke leftists into frenzies unseen in the West since the original Nazi Brownshirts terrorized Jews in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, and it has now reared its ugly head on the American political right. Now is the time to differentiate the right from the left, not to join the left in embracing this toxic fusion of collectivism and antisemitism. Since October 7, I have been stating on X: antisemitism is just the tip of the spear of a collectivist and nihilist ideology that seeks the destruction of Western Civilization. Your videos and statements have made it clear that we embrace as "friends" those who embrace and proselytize these evil ideas under the guise of a big tent on the right in which self-proclaimed conservatives can have friendly and cheery conversations with modern Nazis.

To employ President Ronald Reagan's iconic phrase from his justly famous 1964 speech, today is "a time of choosing." Notably, "a time of choosing" is the same adage used by historians and scholars to describe the 1930s when Germany raced headlong from social exclusion of Jews to political and legal discrimination against Jews, and then in the 1940s to the first industrial genocide in human history. The rise to prominence of the same nihilism and antisemitism on both the American political left and right has made it clear that today is again a time of choosing.

You have made clear your choice: endorsement and toleration of false friends of freedom, rights, liberty, and the American ideals of the Founding Fathers, despite their Orwellian claims to the contrary that they are advocates for America First or represent conservativism. Worse than false friends, they have proven to be advocates for the evil ideologies that seek to destroy these achievements of Western Civilization, as represented by the United States of America — what President Reagan beautifully referred to as the "shining city on a hill."

It is one thing for you to make this choice as an individual, but you have made this choice for the Heritage Foundation. I cannot stand by in silence. It is a time of choosing. I choose to resign.

Sincerely,

Adam Mossoff

The post Why I Am Resigning from the Heritage Foundation (Guest-Post by Adam Mossoff) appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Bernstein] An Extraordinary Panel at the Federalist Society's National Lawyers' Convention

[At at time where moral clarity about antisemitism and radical hostility to Israel has been sorely lacking, the Federalist Society stepped up.]

[Readers: this post has a long windup before it gets to the relevant Federalist Society panel. If your patience wears thin, feel free to scroll to the end.]

The last decade has been an extraordinarily difficult one for Jewish Americans. It began in 2015, when Donald Trump's populist candidacy unleashed a wave of vicious antisemitism on social media from right-wing extremists convinced that Trump was secretly on their side and that his presidency would end what they imagined to be "Jewish control" of the United States.

That same year, the far left surged within the Democratic Party with the rise of Bernie Sanders. After Trump's election, leftist antisemitism surfaced quickly—most prominently in the antisemitism scandal that roiled the Women's March movement and in a venomous campaign against the Anti-Defamation League fueled by fabricated claims of racism.

The intervening years brought a series of horrifying episodes: the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre; antisemitic murders in the New York area by members of radical African-American cults; hundreds of attacks on visibly Jewish pedestrians in New York City; and increasing efforts by activists to exclude Jewish participants who were not openly anti-Israel. Surveys showed antisemitic attitudes rising sharply for the first time since the 1940s, albeit from historically low baselines.

October 7 intensified the troubling preexisting trends. Mainstream outlets have lavished attention on the fringe of Jews who have literally aligned themselves with pro-Hamas activism, while devoting far less attention to the mainstream Jewish community and what it has endured. Many Jews—especially progressive Jews—were stunned that non-Jewish friends showed little empathy or concern for them in the aftermath of the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. Even before Israel mounted any significant counterattack, some of those friends expressed more sympathy for the perpetrators than for the victims.

College campuses where Jews once felt extremely comfortable, such as Columbia and Penn, saw open celebrations of the October 7 massacre. Some SJP chapters even posted images glorifying the Hamas hang gliders used to murder and kidnap civilians in peacenik kibbutzim. Anonymous campus apps overflowed with antisemitic content. Jewish students faced harassment, shunning, and a spate of violence. Universities that had spent years proclaiming their commitment to equity and diversity responded with indifference—and in some cases effectively sided with the Hamasniks.

Off-campus, Jewish institutions and businesses, especially in New York City, were besieged by pro-Hamas demonstrators. Jews lost friends who demanded they denounce Israel, or who simply dropped them because of their connections to Israel. One of my young relatives, who had been teaching disadvantaged children in Israel when 10/7 occurred, returned home after enduring Hezbollah missile barrages. Instead of being welcomed with love and compassion, her longtime friend group disowned her for her ties to Israel. Multiply that story by tens of thousands to understand the emotional landscape.

Meanwhile, the left-leaning organizations with which American Jews have long allied themselves were silent or complicit. Even the ADL's vocal opposition to Trump's Muslim ban did nothing to shield it from left-wing accusations of racism and Islamophobia.

The trauma of the current moment is such that Jews now routinely discuss the "attic test": Would this person hide me in their attic if an antisemitic mob or government agent came looking? Many have realized that people they once trusted might hand them over to the Gestapo—as long as the Gestapo claimed to be seeking "Zionists" rather than Jews.

The broader climate of incitement soon produced deadly consequences: two people murdered after leaving a Jewish event in Washington, DC, and an elderly woman murdered and others severely injured at a rally for Israeli hostages. Some influential far-left accounts applauded the violence with minimal pushback from mainstream progressives. And the fact that Zohran Mamdani—a Hamas sympathizer who spread the absurd antisemitic trope that NYC police brutality was Israel's fault—could become mayor of New York City illustrates the political space now available for such views.

On the right, early expressions of solidarity with Israel and denunciations of campus antisemitism gave way to a rise in antisemitic Groyperism. Several Trump nominees turned out to have overtly antisemitic social-media histories. Candace Owens and Tucker Carlson drifted from "just asking questions" into disseminating unabashedly antisemitic content. Nick Fuentes became one of the country's most popular podcasters. The president of the historically pro-Israel Heritage Foundation defended Carlson and declared he saw no reason to "cancel" Fuentes. Today, right-wing social media is a sewer of conspiracism, Holocaust denial, and open Jew-hatred reminiscent of the 1930s.

Two aspects of this environment are especially devastating. First, Jewish institutions increasingly resemble armed camps, a constant reminder to Jewish Americans of their vulnerability to violence from extremists of the left, the right, Islamist radicals, and assorted kooks and cultists.

Second, political actors on both sides are actively stoking antisemitism because they see it as electorally useful. The far left has weaponized radical "antizionism"—often indistinguishable from antisemitism—to differentiate itself from the Biden administration and purge the Democratic Party's moderates before 2028. The far right's nativist isolationists, disappointed that Trump not embraced their agenda, have similarly turned to demonizing Israel and American Jews as a strategy for post-Trump influence. This marks the first time since the 1930s that being anti-Jewish is often a political positive.

In the face of this hostility—some sincere, some cynically manufactured—very few organizations outside the Jewish community have shown genuine solidarity.

That is why, as a Federalist Society member for 37 years, I was profoundly moved by a two-hour plenary panel at last week's National Lawyers Convention.

The panel opened with Senator Ted Cruz unequivocally denouncing right-wing antisemitism and calling out Tucker Carlson by name. It continued with a discussion featuring nine federal judges and one state supreme court justice—most not Jewish—many of whom had visited Israel with the World Jewish Congress.

The full panel is available online. Every panelist—Catholics, Jews, Mormons, evangelicals, mainline Protestants—did one or both of the following: denounced antisemitism or defended Israel as a vital outpost of Western civilization against the terrorist barbarism of Hamas, Hezbollah, and their allies. Judge Amul Thapar delivered an especially forceful defense of Israel. I was deeply moved by Judge Elizabeth Branch's comment, paraphrased here: "My mom reminded me that I have always stood behind my Jewish friends. I have decided that now is the time to stand in front of them."

Since October 7, I have not seen anything remotely comparable—a group of highly influential Americans from diverse religious backgrounds speaking with such moral clarity on behalf of what many of them referred to as their "Jewish brothers and sisters."

This panel also delivered a clear message to the Groypers: you are not welcome in the Federalist Society. If you are a law student who allies with antisemites, you should not expect a clerkship or access to the Society's extensive network of distinguished lawyers.

The moral clarity shown by the Federalist Society and its president, Sheldon Gilbert, has been almost entirely absent in elite American discourse since October 7. Even many Jewish organizations outside the far left have struggled to defend the Jewish community without hedging. I hope others will follow the Federalist Society's example—but I am grateful even if they do not.

The post An Extraordinary Panel at the Federalist Society's National Lawyers' Convention appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers